#PROTESTEMOS

Projetemos, São Paulo, 2021

It was curator Marília Pasculli who best described the unprecedented movement that took place in Brazil in 2020 at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic: “When the walls get voices.” That statement appeared as the title of an article Pasculli authored last June. [1]

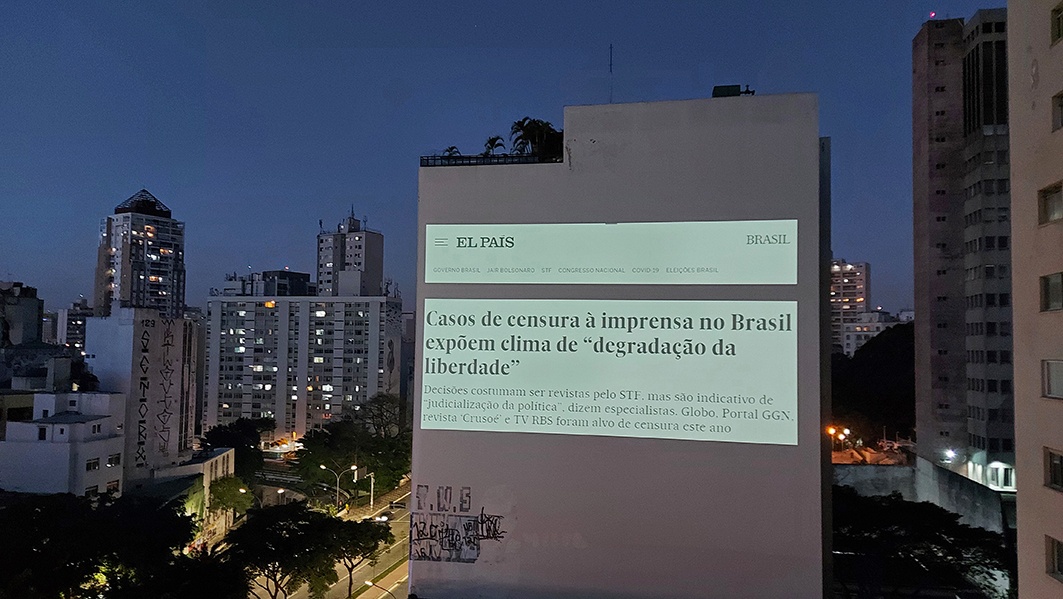

As a result of social distancing measures, projectionists substituted protesting on the streets with protesting from windows. Instead of the usual gigantic structures used to cast video mapping onto the sides of buildings, facades, and walls, a projector and a computer with internet access are the basic tools that have made projections more accessible and easier to disseminate. Previously limited to activism and the arts, projections have reconfigured urban space in Brazil, engaging themes related to news, politics, human rights, services, and entertainment, as well as streaming live broadcasts of the Parliamentary Inquiry Committee (CPI) proceedings, which investigated the federal government’s actions during the Covid-19 pandemic, or of the fashion show held at São Paulo Fashion Week (SPFW), for example. [2]

Daily declarations now appear in the landscape of Brazilian cities: “Respect every form of love”; “How long will we keep on dying?”; “SUS [Sistema Único de Saúde] is a myth”; “Stray bullets always find a Black body”; “Cultivating love eases the pain”; “What will you do when you are vaccinated?”; “Every day is Earth Day”; “Freedom”; “Stop killing Native South Americans”; “We are running the Covid CPI marathon”; and “Mourning for Brazil.” [3] This popularization took place thanks to Projetemos (Let’s project), a collective-action group responsible for creating a national network of projectionists, with participants from five Brazilian regions – with major participation in Minas Gerais in the southeast – in addition to collaborators from Argentina, Italy, Chile, France, the United States, and Colombia, among other countries. The hashtag #PROJETEMOS circulated through social media, starting with Movimento Nacional (National Movement), which first appeared on March 21, 2020.

The call-out issued by Movimento Nacional gave rise to protests, carried out almost simultaneously across the country, against President Jair Bolsonaro’s Covid denial and his countless attempts to sabotage public health measures adopted by mayors and governors to stop the spread of the virus. They have included Bolsonaro’s endorsement of the use of ineffective medication against Covid-19, as well as his encouragement of social gatherings and the nonuse of masks, which have led thousands of Brazilians to their deaths and caused incommensurable damage. At the third major mobilization against Bolsonaro, in July 2021, the Planalto Palace – the president’s official workplace, situated in the Ministries Esplanade in Brasília – was lit up in projections denouncing Bolsonaro. Motivated by the accusation published by Folha de São Paulo, one of the country’s most important newspapers, that a Health Ministry official asked for a bribe in exchange for approving the purchase of thousands of AstraZeneca vaccine doses, approximately 800,000 Brazilians took to the streets in all state capitals, outnumbering previous demonstrations held on May 29 and June 19. Related protests also took place in England, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Ireland, and Portugal.

Ciro Gomes, „Bolsonaro traidor: Mais atual do que nunca!“, 2021, Filmstill

This was not the first time this kind of action took place at the Palace. On June 20, the day following the second demonstration against the president, a group of artists – organized by Bruno Caramori, aka Boca, a member of Projetemos, and the artist Gabriela Tornai – projected the message “500,000 victims” for eight minutes on the walls of the National Library of Brasília and the federal capital’s main bus terminal, which are located just a few kilometers from the seat of the federal government. This, however, was not the first time a president was the subject of this kind of scrutiny. Former president Dilma Rousseff had also been targeted with protests against her administration: on March 21, 2016, nearly two months after the process of removing her from office was sanctioned by the Senate, activists from opposition parties projected the word “impeachment” on the Planalto Palace walls.

National Network

Under the motto “With the right organizing, everybody can project!” (“Se organizar direitinho, todo mundo projeta!”), the national network of free projectionists provides, besides its novelty, an educational role in society. The group, coordinated by VJs Mozart and Felipe Spencer and by political scientist Bruna Rosa, holds workshops that teach people how to project, and, at www.projetemos.org, it supplies a template where anyone can submit suggestions for messages to be displayed on a building’s exterior. As Lucas Pacífico described in his 2020 book Onde nos encontramos (Where we find ourselves), “The true revolution on the streets is now at home.” [4]

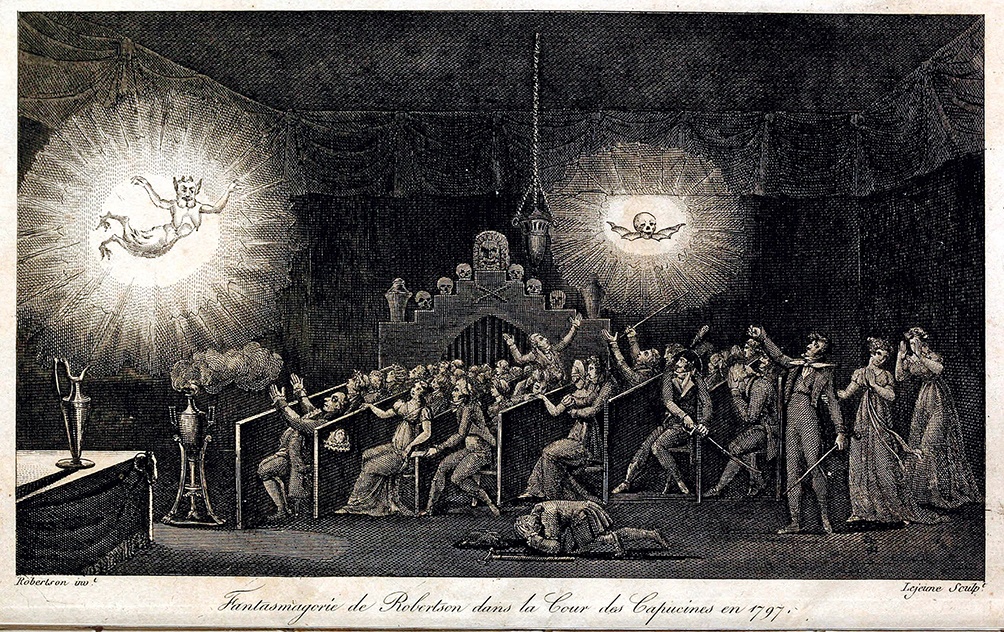

Besides Projetemos, other groups, such as Projeção Consolação, Cine Janela, Cine Minhocão, Fortuny.DJ, Rede Quarentena, and VisualFarm, have come together with the intent of projecting. Projeção Consolação was founded in 2019 with the objective of carrying out daily projections, but its last Instagram update was posted on March 18, 2020. The remaining groups are still active, though they do not organize actions with the same frequency as Projetemos. Nevertheless, projections made in urban space are nothing new. Experimentation with projection techniques began in the eighteenth century. The pioneer of projection technology and its aesthetics was the physicist and magician Étienne-Gaspard Robert, whose performance technique, called phantasmagoria, was “the result of the condensation of several optical illusion experiences, consisting in mounting a magic lantern on rails to produce characters and figures of different sizes, which are projected on smoke.” [5] The modern application of projection in urban space in Brazil and beyond has been in practice for at least two decades.

In his 2017 book Mappingfesto: Projection Mapping Manifesto, the VJ Alexis Anastasiou narrates the genesis of the use of this technology in the Brazilian context: “Brazilian VJs started their real-time video mixing work by following the rhythm of electronic dance music beats played at parties, clubs, and raves in the late 1990s. In those days, the access to digital video production tools was extremely limited and difficult.” Regarding the exact technology these VJs used, Anastasiou notes that “a digital workstation, with the capacity to produce videos and basic animations, cost a small fortune back then. The most used tools were VHS videocassettes, which transmitted analog videos in a very questionable quality, and primitive computers (incapable of running videos).” [6] Although projections had already been utilized for more than two decades in Brazil, Anastasiou’s Vídeo Guerrilha project, aimed at reimagining the public function of the street, is considered the first major video mapping action.

Revisiting Anastasiou’s book now is important because the accounts he provides foreshadow the daily projections of March 2020, not aesthetically but in their process – the way in which they are produced and the extent of their production and access. Today, anyone with a projector, a computer, and internet access can take part in collective actions. At the same time, unlike demonstrations that are traditionally carried out on the streets, the political application of projections is governed by legal restrictions in some Brazilian cities. In the city of São Paulo, the Clean City Law, in force since 2007, prohibits political demonstrations made through projections. According to a resolution issued in 2011, “the temporary projection of films, cartoons, photographs, and images in general, on permanent or temporary, public or private building facades, monuments, civil infrastructure, and other such constructions, when visible from public streets, must be approved in advance by the head of the Urban Landscape Protection Committee.” In other Brazilian states, including Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, there are no such regulations. But when artists and activists in São Paulo infringe upon the law by projecting, they can be fined R$10,000. Despite the risk of being punished, projectionists have found new ways to get around the law, often by changing the location of their posts on Instagram, the social media network most used to publicize their actions.

Étienne-Gaspard Robert, „Fantasmagoria de Robertson dans la Cour des Capucines en 1797“, 1831

Related legislation that, by contrast, decriminalizes graffiti was sanctioned by former president Dilma Rousseff in 2011. This law distinguishes liabilities: graffiti done on any property belonging to the state is to be authorized by the government, whereas graffiti done on any private real estate is to be authorized by the owner and/or tenant. Even if new legislation inspired by the decriminalization of graffiti is considered in governing projections, we are still confronted with a problem: the political interests of private real estate owners.

For this reason, the courts are currently reviewing whether or not the enforcement of the Clean City Law, within this context of political protests, is an infringement of the Brazilian Constitution, which, according to Article V, guarantees freedom of speech. There is another very important issue in this regard: it is the local government that decides whether or not authorization is granted, which obviously entails the frequent refusal of requests related to projections that are political in nature, especially if they are meant to protest against the local government’s political allies, for instance. [7] That leads us to the following question: If demonstrations and protests are now conducted and made on facades, walls, and the blank sides of buildings – in public space – why does the government get to decide on the content that can be displayed in the projections?

Floating Screens

Alongside the political aspect of projections, there are also educational actions, such as those carried out by the group Não Bata, Eduque (Don’t spank, educate). Through videos, the group has been teaching people how to create homemade projections using smartphone flashlights to mobilize individuals to participate in the group’s political messaging from home. Such an action took place at a demonstration against domestic violence and child abuse on June 26, 2021.

Projetemos and Não Bata, Eduque are closely related to the postgraduate program I participated in at the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAUUSP) from April 2018 to January 2021. It was thanks to #PROJETEMOS that I was able to prove the hypothesis of my final paper: that ephemeral projection screens would be employed on a mass scale for political action around the world in the near future.

The idea of addressing projections in my research project originated from the short film Lost Memories, released in 2012 by the French director François Ferracci. The film’s plot takes place in Place du Trocadéro in Paris, depicted as a site awash in data and in which connection is ubiquitous and digital interfaces expand beyond smartphone screens. As a result, the urban landscape is surrounded by floating and temporary screens, creating an augmented reality. Although the main concern of Lost Memories is to point out the risks of a society that is totally dependent on digital data, the primary concern with the real-life implementation of this development is related to the aesthetic, ethical, and political implications of a city reconfigured by screens.

Projetemos, São Paulo, 2021

At the time, my best guess was that the ubiquity of this technology would become reality sometime soon, but with smartphones, not with the projectors used in March 2020. [8] The belief was that augmented reality applications would place these interfaces into urban space. After I conducted several surveys to identify how this kind of mobile device should be used to this end, simpler ways of augmenting urban space emerged all over the country – despite what I had previously imagined.

The effect of the projections of March 2020 is similar to that described by Anastasiou when referring to digital facades in his 2017 book: “The building facades of any given city become dynamic systems that interact with the streets in real time, causing and receiving interference from its inhabitants.” Anastasiou wrote that the large-scale and permanent use of these techniques would make it possible to change the appearance of buildings just as easily as we can now change the wallpaper of our desktops and smartphones. [9]

It happens, however, that these dynamic systems need authorization to be displayed in some locales, as is the case in the city of São Paulo, where the Clean City Law is enforced, except regarding themes connected to Covid-19 and projections carried out by a public agency. However, the projections of March 2020 made people wonder whether there is the need for specific federal legislation to replace local regulations. It seems appropriate to consider the creation of federal legislation on the subject. Perhaps the solution is a General Law of Digital Culture, like the one I suggest in my final report; such a law could establish parameters for use of these ephemeral screens, as based on a broad discussion carried out by a qualified group of people that can list relevant criteria for evaluating these projections. The need to consider amending the old laws or creating new legislation that addresses the issue of projections is urgent, since these movements are not going away. Indeed, they are already part of the urban landscape and have modified the way people interact and protest in urban space.

The effect of the projections of March 2020 is evident in the national network created by Projetemos during the following two years of social distancing. There are approximately 200 projectionists scattered throughout Brazil today. It is a movement that has come to stay – not only because of the political dimension it has reached, but because of its complete reconfiguration of Brazilian culture: people watch television programs, movies, and live coverage of fashion shows and political news; participate in political actions taking place simultaneously in several countries; and receive health information through these projections. The work of these various collectives has consolidated the democratic occupation of the urban landscape as a daily practice and forced a debate on outdated legislation in relation to this new contemporary context and in defense of freedom of expression.

Notes

| [1] | Marília Pasculli, “When the Walls Get Voices,” Volume, June 21, 2021. |

| [2] | Fabio Victor, “Luzes na cidade. Ativismo num paredão paulistano,” piauí, March 2020. |

| [3] | All translations by the author. |

| [4] | Lucas Pacífico, Onde nos encontramos (São Paulo: self-pub., 2020). |

| [5] | André Parente, “Do quase ao pós-cinema: o cinema como efeito,” in Novas formas do audiovisual, ed. Lucia Santaella (São Paulo: Estação das Letras e Cores, 2016), 125. |

| [6] | Alexis Anastasiou, Mappingfesto: Projection Mapping Manifesto (São Paulo: Visualfarm, 2017), 71. |

| [7] | The complete version of the final postgraduate report is available at https://bit.ly/3wtmH2J. |

| [8] | Luciana Moherdaui, “Telas urbanas: do neón às projeções efêmeras,” Galáxia (São Paulo) 45 (September and December 2020): 179–93. |

| [9] | Anastasiou, Mappingfesto, 45. |