KAFKA’S HALT!

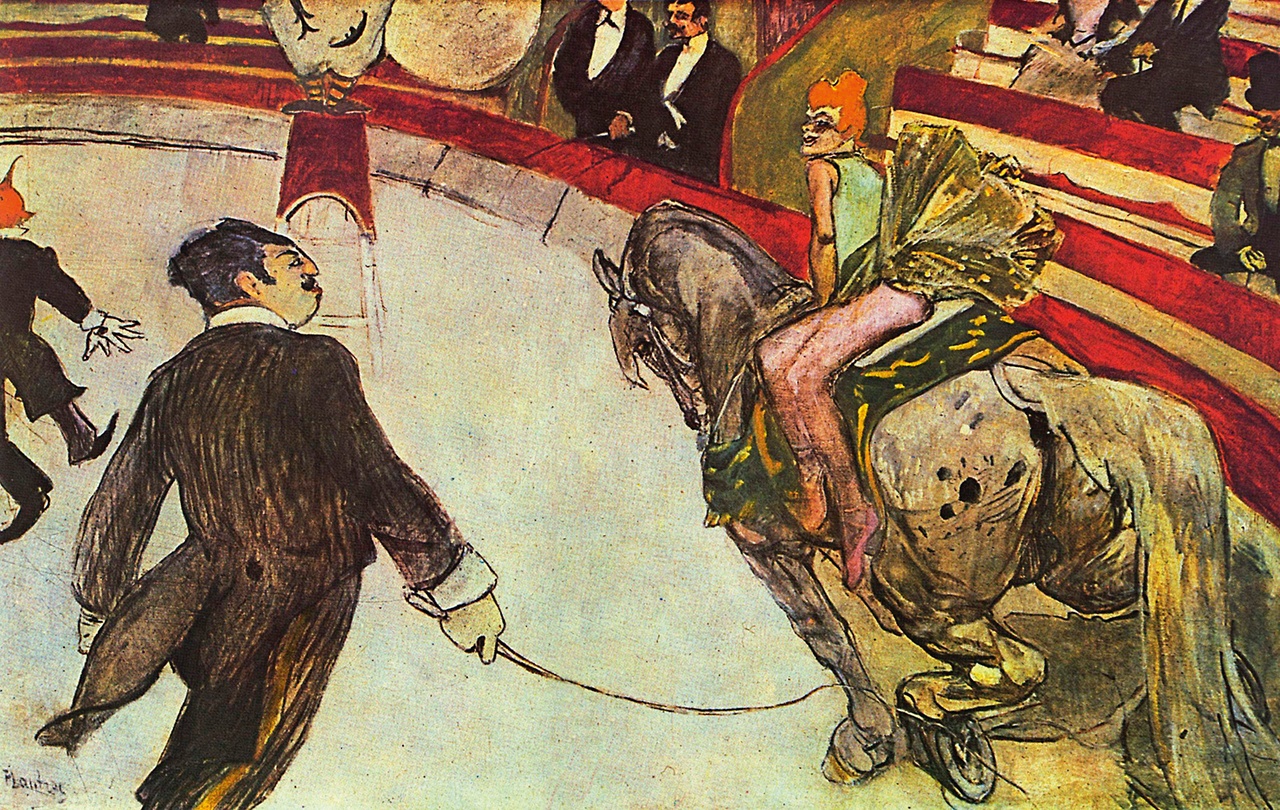

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, „Au Cirque Fernando, l’Écuyère“ / “Equestrienne (at the Cirque Fernando),” 1887–88

If it were evident that the circus rider in Kafka’s story “Up in the Gallery” is really an ailing artist teetering on a horse before a tireless audience, that she is driven mercilessly in a circle by a cruel director, and that this will continue ceaselessly into the most distant gray future – if the world were to show itself in its absolute despondency – then the young visitor up in the gallery would, without hesitation, rush down into the ring to intervene and “shout ‘Halt!’” [1] That the world, in the indicative mood of our everyday perception, appears not in its precipitous decline but suffused with the warm glow of our illusions requires the revelation that the fair lady we believe to see before us is, in reality, consumptive, that the devoted director is a despot, and that the ovations of the audience are “steam hammers” stifling our outrage and preventing the potential savior from assessing the situation and putting an end to its unending horror.

Published in the collection Ein Landarzt (A Country Doctor) in 1919, Kafka’s short text – a mere two paragraphs – illustrates the need for an unauthorized outsider’s spontaneous resolution to stand up against observed tyranny as well as the obstacles that discourage him from putting a stop to the violent way of the world. The fact that his interference takes the form not of a physical intervention but of an exclamation, the single word “Halt!”; that no other motivation propels the young man but his response to what he is witnessing; that he is acting of his own accord and without the support of others suggest that Kafka’s gallery spectator is not a professional revolutionary but a character who might abruptly leave his place – a cheap seat high up, giving him an overview afforded by distance – and, armed with nothing but language, interrupt the run of events.

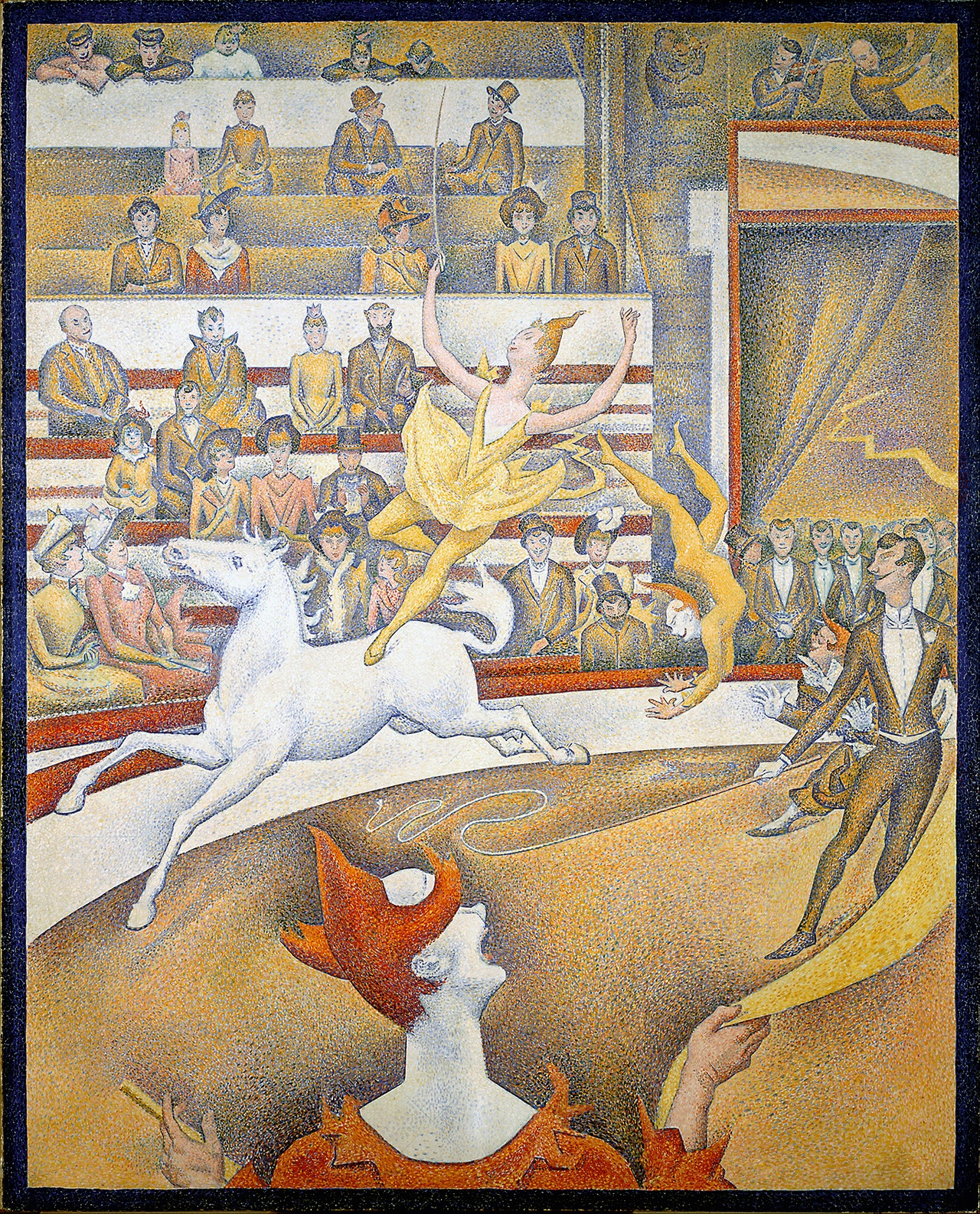

Georges Seurat, „Le Cirque“ / “The Circus,” 1891

The mode of Kafka’s story is disconcerting and runs counter to the reader’s expectations: the first paragraph describing the cruel circus scene – the wrong life – is written, quite counterintuitively, in the subjunctive, whereas the second paragraph, revisiting the scene only to paint it over in glorious colors, is in the indicative. The text’s conclusion is no less baffling: “since this is so,” that is, good and beautiful, “the gallery visitor puts his face on the railing and, sinking into the concluding march as into a heavy dream, he weeps without realizing it.” [2] The narrative ends with an escape into dream aided by the rush of military music. The injustice perceived in the first paragraph only to be repressed in the second leaves behind a residue of unconscious mourning. Through its volatile perspective, Kafka’s text lets the reader experience how the evidence of evil is whitewashed so that the spectator can in good conscience remain up in the gallery. The failure to have rushed down from his seat, to have called out “Halt!,” to have intervened, precipitates as a tear that is no one’s and nowhere.

Yet this is literature, and so our finding is only conditionally correct. What the young visitor up in the gallery represses is transposed onto the reader as an irritation prompted by the commutation of modal forms, narrative perspectives, and linguistic registers. Perturbed, we try to set the narration’s warped features straight, to smooth out the inconsistencies. We experience for ourselves the measures required to lend order and meaning to things, and in so doing we reproduce the very dynamic of self-deception that the story is about. Like the text, the experience of reading ends with a resistant residue, an intimation of the futility of our undertaking. What is thus revealed – and perhaps this revelation is only possible in this literary mode, which does not fend off contradictions or sanction transgressions against norms, performing the simultaneity of opposites for an illuminating experience – is not so much the lie of beautiful appearance or the true bad world behind the false good one. Rather, what we experience reading Kafka’s text is how we ourselves stage-manage our world and paint it in glorious colors to impose a familiar and expected order.

To read Kafka’s narrative in this manner is patently already to interpret it, to make several adjustments to the text’s wording in order to lend meaning to the whole. Yet unlike moral sermons, political tracts, or religious revelations, which are based on existing value systems, Kafka’s text resists even such an ultimately soothing final unveiling of things as they really are, or even a mere pragmatic reduction of the warped wording to an unequivocal imperative. Would the gallery visitor rushing down be a courageous intervention or alarmist hyperbole meant to justify a dream of heroism? Is the unconscious mourning with which we are left a residue of dismay over the circus artist’s bitter fate? Is it a token of bad conscience over the cowardly escape into a dream or of the merely narcissistic regret over the failure to act heroically? The decision between these alternative possibilities is left in abeyance. That the narrative’s indirection and undecidability might put a halt not only to the escape into dream but also to the call for a halt is the risk – and, by the same token, the chance – in this serious game called literature.

August Macke, „Zirkus“ / “Circus,” 1913

Kafka’s story does not offer directions for the right life, an example of Walter Benjamin’s observation that Kafka “failed.” Kafka, Benjamin wrote, “counted himself among those who were bound to fail. He did fail in his grandiose attempt to convert poetry into teachings.” [3] Yet as Benjamin noted in a letter to Scholem, “once he was certain of eventual failure, everything worked out for him en route as in a dream.” [4] It is easy to recognize that Kafka never arrived at teachings, at a doctrine, but his success – what supposedly “worked out” here and, moreover, “in a dream” – remains vague. The locution of failure and success presupposes existing criteria and an associated set of values, which is what Benjamin’s paradox of successful failure subverts. The latter might imply the success of an intervention that, rather than being derived from rigid premises, rescinds those premises and now responds without support or volitional calculation to what is perceived. The artist and writer’s sense of impotence, Benjamin suggests, is not an indication of failure but the consequence of the refusal to participate in the powerful’s discourses of power. The young spectator who fails to run down and interrupt the spectacle reflects Kafka’s doubts about the possibility of intervening into the world by means of literature. The paralysis of the young man up in the gallery would then not necessarily amount to a failure; it might signify his refusal to take part in the circus and its stabilizing discourses.

It is precisely where art and literature do not aim at an effect, where they neither proceed from fixed intentions nor arrive in a predetermined place, that they engender a simultaneity of urgency and distance. And nowhere is that simultaneity enacted more forcefully than in the theater – and, as the case may be, the circus – with its distinctive tension between involvement and distanced observation. The posture of Kafka’s spectator can interrupt the totalizing circle drawn by the sickly rider into the grayest future and, to quote Kafka’s starkest description of his dream attached to his own writing, “leap out of the murderer’s row of action – observation – action – observation.” [5] Kafka, in the same sentence, understands writing as “a higher form of observation” that interrupts the dichotomy between passive contemplation and active intervention. [6] In its stead, literature enacts and performs, creating its own form of intervention.

Franz Kafka, Zeichnung einer reitenden Figur / Drawing of a figure on horseback, ca. 1903–07

Arguably, Kafka describes the condition for such a leap out of the totalizing discourse of oppositions nowhere more succinctly than in a formidable paragraph in his diary dated November 20, 1911:

My repugnance for antitheses is certain. They come unexpectedly, but do not surprise, for they have always been very close at hand; if they were unconscious, it was merely at the very edge of consciousness. They make for thoroughness, fullness, completeness, but only like a figure on the “wheel of life”; we have been chasing our little idea around the circle. They are as undifferentiated as they are different, they grow under one’s hand as though bloated by water, beginning with the prospect of infinity, they always end up in the same finite medium size. They curl up, cannot be straightened out, provide no foothold, are holes in wood, are immobile assaults [stehender Sturmlauf], draw down antitheses to themselves, as I have shown. If they would only draw all of them down upon themselves, and forever. [7] (Emphasis added)

As Kafka argues, antitheses – a term in logic for dichotomous oppositions – lack the capacity to startle because, “at the edge of our consciousness,” they are always already implicitly contained in the initial idea (as the yes is contained in the no) and thus caught in a closed loop. To achieve circular totality through the joining of opposites comes at a cost: in spite of their seemingly enlivening contrasts, antitheses lack nuance and distinction, producing nothing but the mediocrity and stasis of closure. Crossing the seeming contradiction between opposition and circle, Kafka invokes the “wheel of life,” a toy with static drawings on the inside of a wheel. [8] When the wheel is spun around, an optical illusion is created where the drawings appear to become animated. Such blocked energy is evoked in the most famous image in this passage, a metaphor often (erroneously) used in a positive sense to describe Kafka’s writing: the “immobile assault” (stehender Sturmlauf), a paralyzed force fueled by mutually short-circuiting oppositions, is what Kafka’s writing continually performs only to undermine it. [9] The passage ends with a yearning in the guise of a curse: may antitheses, which always only produce more antitheses, “draw all of them down upon themselves, and forever.” Yet this remains Kafka’s wishful thinking. At the most, the operation of antitheses can be exposed.

David Marton, „Die Heimkehr des Odysseus“ / “The Return of Ulysses,” Schaubühne, Berlin, 2011

Kafka’s explanation of his “repugnance for antitheses” bears a striking resemblance to his technique in “Up in the Gallery.” Like the ringmaster driving the equestrienne – also called die Kleine (the little one) – in an endless circle, antitheses are merely “chasing our little idea around the circle.” [10] Staged as a near-perfect antithesis, however, “Up in the Gallery” also proves to be its antidote. Although the story opposes glory to gloom, beauty to bleakness, and care to cruelty, the second paragraph sends minute signals that crack its symmetry and undermine the credibility of the attractive circus scene. The presence of “curtains,” for instance, absent in the first paragraph, points to an artificial spectacle hiding a backstage. This impression is reinforced by the grotesque exaggeration of the director’s gestures – his heavy breathing, animal-like posture, open mouth, and mannered English exclamations. The reader gradually comes to suspect that the perspective in this second paragraph is that of the hardly credible circus director: it is he who “cannot make up his mind to signal with the whip,” who “finally pulls himself together and cracks it smartly,” who “scarcely believes her skill,” who “considers no tribute from the public satisfactory enough,” and, most conspicuously, who patronizingly calls the female acrobat “the little one.” She, in turn, is shown in a peculiar and ambivalent light: at the very moment when she “tries to share her bliss with the entire circus,” she has “her arms outspread, her head thrown back,” like the ultimate sacrificial sufferer on the cross, Christ himself. [11] This hidden hint pointing back to the tortured creature in the first paragraph further erodes the believability of the beautiful spectacle in the second one, introducing an unsettling simultaneity of misery and glory that subverts the story’s antithetical structure.

These barely perceptible cracks in the surface of the second paragraph create the suspicion that the beautiful scene, its indicative mood, and the emphatically repeated reassurance that “this is so” are not to be trusted. They undo the neat opposition between this splendid scene and the first paragraph’s distressing one, the reality of which had initially been undermined by the subjunctive mood. As a result, the reader is left disoriented, with nothing but the perturbing experience that the ordering principles of the antitheses have become untenable. We are faced with the impossibility of reaching the “thoroughness, fullness, completeness” that antitheses establish. Our quest for a Halt! – be it an interruption, be it a foothold – is itself halted. And so we exit the closed arena, if only for the duration of our reading, before the next antithesis inevitably circles into view. Undoing the logic of oppositions once and for all will remain Kafka’s unfulfillable dream. Although it must inevitably fail, to be pursued anew in each instance, this experience may be the ultimate gesture of dissent that literature and art have at their disposal.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Vivian Liska is a professor of German literature, the director of the Institute of Jewish Studies at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, and since 2013 Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. She is an author of When Kafka Says We (Indiana University Press, 2009), Fremde Gemeinschaft. Deutsch-jüdische Literatur der Moderne (Wallstein, 2011), and German-Jewish Thought and Its Afterlife: A Tenuous Legacy (Indiana University Press, 2017), among others.

Image credit: 1. CC0 1.0 Universal, Public Domain, Art Institute of Chicago; 2. CC0 1.0 Universal, Public Domain, Musée d'Orsay; 3. CC0 1.0 Universal, Public Domain, Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum; 4. Courtesy of The National Library of Israel, Max Brod Archive; 5. Photo: Heiko Schäfer

Notes

| [1] | Franz Kafka, “Up in the Gallery,” in The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (New York: Scribner, 2000), 244. |

| [2] | Ibid., 245. |

| [3] | Walter Benjamin, “Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, vol. 2, 1927–1934, eds. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 1999), 808. |

| [4] | Walter Benjamin to Gerhard Scholem, June 12, 1938, in The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin, 1910–1940, eds. Gershom Scholem and Theodor W. Adorno, trans. Manfred R. Jacobson and Evelyn M. Jacobson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 566. |

| [5] | Franz Kafka, Tagebücher in der Fassung der Handschrift, eds. Hans-Gerd Koch, Michael Müller, and Malcolm Pasley, in Schriften, Tagebücher, Briefe, eds. Jürgen Born et al. (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1990), 892. |

| [6] | Ibid. |

| [7] | Franz Kafka, The Diaries of Franz Kafka, ed. Max Brod (New York: Schocken, 1965), 157. |

| [8] | In a footnote to this passage in Kafka’s diaries, Max Brod describes the “wheel of life” as a “toy through the aperture of which one perceived the successive positions of a figure affixed to a revolving wheel. It thus creates the illusion of motion.” |

| [9] | See, e.g., the title of the audiobook Stehender Sturmlauf. Leben und Werk Franz Kafkas, read by Rufus Beck and Alexandra Maetz (Berlin: Der Hörverlag, 1997). |

| [10] | Kafka, Diaries, 157. |

| [11] | Kafka, “Up in the Gallery,” 244–45. Translation modified; Neugroschel translates “die Kleine” as “the girl,” but it has been translated throughout this text as “the little one.” |