NINE LIVES OF LABOR

Helke Sander, „Eine Prämie für Irene“ / “A Bonus for Irene,” 1971, Filmstill

How do you tell someone that they are in a more precarious position than they realize? Think of Elio Petri’s The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971), Helke Sander’s Eine Prämie für Irene (A bonus for Irene) (1971), Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (1972–73), Helma Sanders-Brahms Der Angestellte (The employee) (1972), Sidney Sokhona’s Nationalité: Immigré (1975), Paul Schrader’s Blue Collar (1978), and Bill Duke’s The Killing Floor (1984): in each film, there is a scene in which Worker A tries to persuade Worker B to stand with their colleagues and join the strike that is looming because management did something outrageous like cut off their promised bonus, fire Worker C for a minor mistake, or plan to offshore parts of the factory. Worker B then says that they heard about it but will not participate because management will retaliate, or because Worker C wasn’t a good worker, or simply because it’s not their problem. Depending on the film’s ending, Worker B is either persuaded that it is in their interest to stand in solidarity, leading the entire unit to a hard-won but temporary victory – such as in Fassbinder’s, Sander’s, or Sokhona’s contributions to the list – or they stick to their committed individualism, leading to a more or less fatal blow to the entire endeavor, such as in Petri’s, Sanders-Brahms’s, Schrader’s, or Duke’s films.

Paul Schrader, „Blue Collar“, 1978, Filmstill

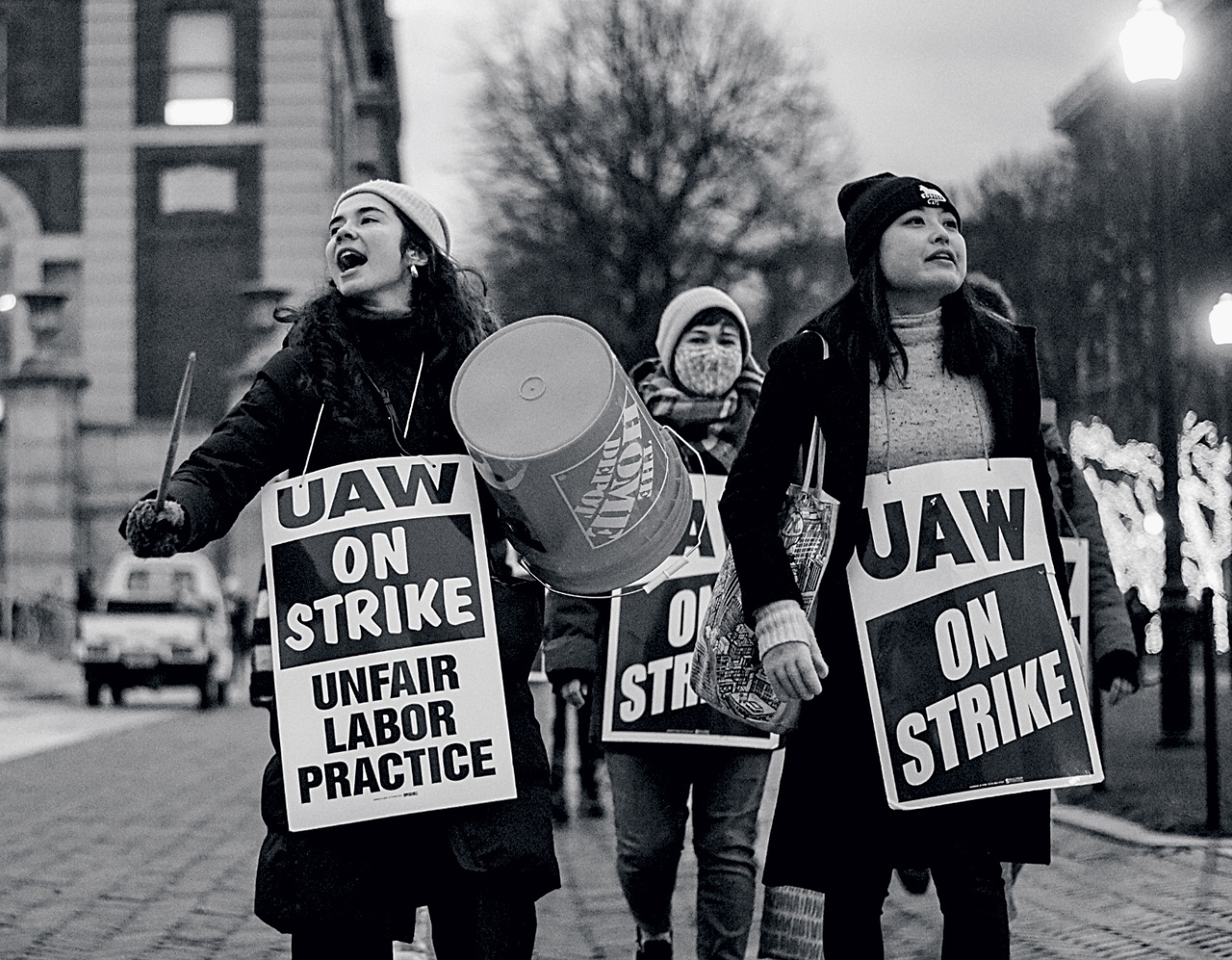

As an organizer of the strike by the Student Workers of Columbia (SWC), organized under UAW Local 2110, you will be familiar with this scene because you have occasionally experienced it whenever you weren’t preoccupied with the other tasks that labor organizing entails: contributing to endless email chains late at night; attending hours-long committee meetings and working groups; revising pages and pages of Google docs for student and faculty outreach emails, trying to counter Columbia University’s efforts, backed by boundless resources, to flood the campus with misinformation in order to divide the strikers and undermine solidarity.

But no matter how much time the other tasks require, the bread and butter of organizing the largest active strike in the United States (as of January) – and, at ten weeks, the longest strike in higher education in over a decade – will remain the one-on-one conversations that you first started when the 3,000-member unit began to prepare for a strike in October to demand a living wage, child-care subsidies, a health-care plan that includes dental insurance, union security, neutral arbitration for power-based harassment, and the recognition of casual workers as part of the unit. And, every once in a while, you will get to meet Worker B, who might tell you: “We are so privileged, shouldn’t we be grateful for what we get? After all, we are at a prestigious institution, getting paid to study, getting paid to do what we love!” Or they will tell you: “There are other graduate workers earning even less than we do.” Or: “I want to have teaching experience and research experience on my CV.” Or: “I fear retaliation from my employer/advisor/professor.” Or, the bleakest of them all: “I’m busy, can you come back later?”

Yes, you will encounter a pattern in your conversations with Worker B, a pattern that is simultaneously rich and beautiful and repetitive and disturbing like a thickly woven Gabbeh carpet or something like that. And as Worker B’s skeptical questions position them within this great pattern, they expose how much experience they have had with collective workplace struggles (sometimes not much, given the atomized middle-class backgrounds from which many graduate students at Columbia come), how much one identifies with a university whose massive wealth is partially based in a five-billion-dollar hedge fund, and how much one overestimates the power of faculty to determine one’s success on the job market. And in this moment of revelation, you might realize that these conversations catapult you into Worker B’s home in a more direct way than most other things you could be talking about. In fact, you might come to think that each of these conversations allows you to observe the whole family of Worker B sitting at the dinner table – eating, talking or not talking, hearing the knives screech as they cut into food on their plates – with you sitting in a corner of the room, an undetected witness like the carpet on which the table stands.

And you will listen to Worker B’s explanations; you might even smile politely when they lash out angrily at you, compensating their guilt with resentment; and you will tell them the same stories, the same arguments, the same facts. You might start with the segment of WNYC’s Brian Lehrer Show you accidentally listened to in May of 2020 when a Columbia PhD student called in to talk to New York City’s then-mayor Bill de Blasio, describing how she had planned to live with her family during the summer to save on rent but was forced to stay in New York because of the pandemic. Earning well below the annual $40k that is the minimum threshold of a living wage in New York City, she wasn’t able to pay rent for the summer, couldn’t obtain funds from her parents in Honduras, wasn’t allowed to take on extra work because of visa restrictions, and, most importantly, wasn’t able to default on rent because her landlord happened to also be her employer: Columbia University, which would simply put a hold on her registration if she didn’t pay rent, thus making it difficult, if not impossible, to return for the fall semester in order to generate new income that would allow her to pay off her debt. So, you might try to break through the vocabulary of privilege – at this point only functioning to legitimize (self-)exploitation – and instead narrate the vicious cycle of dependency in which many graduate workers find themselves.

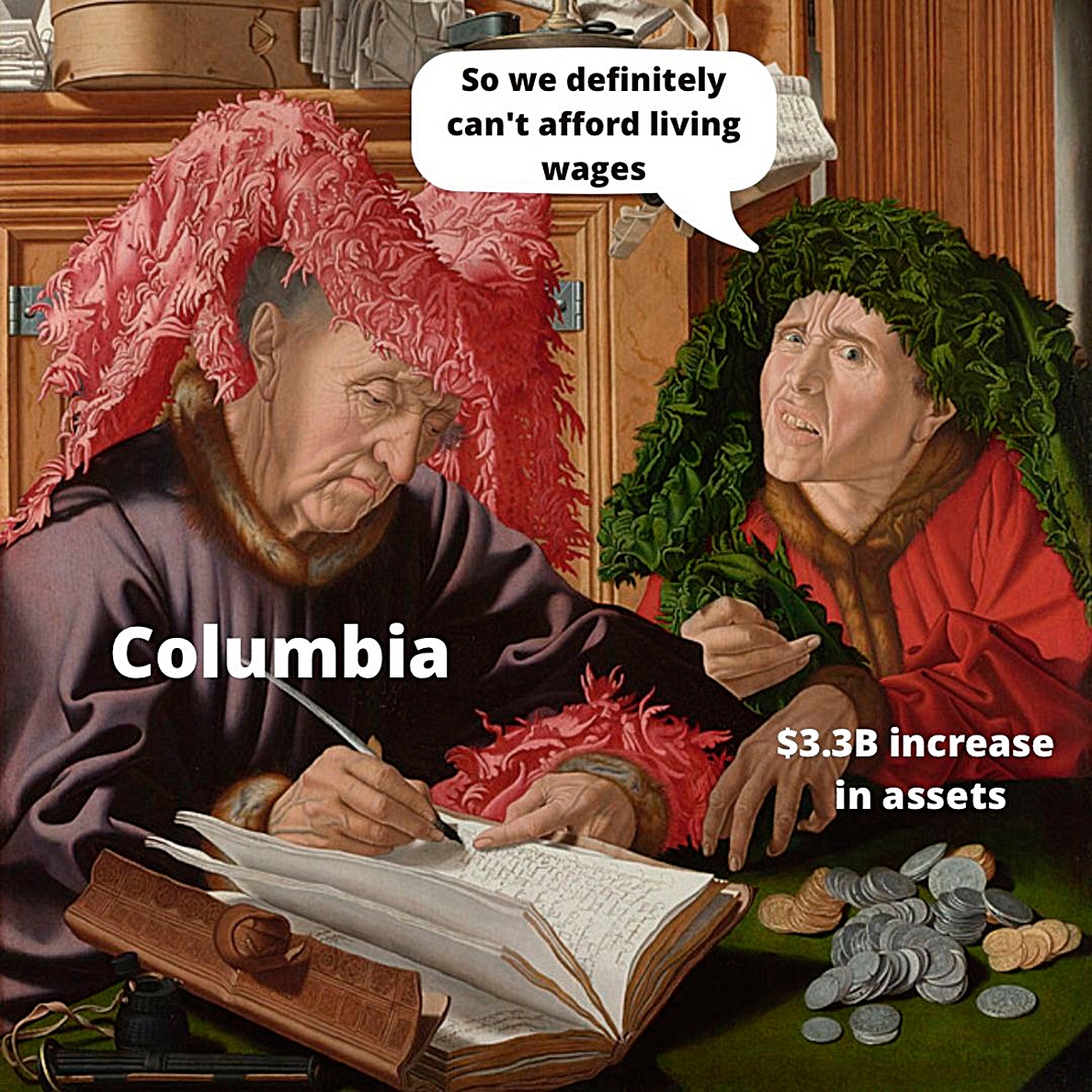

Meme von / by Student Workers of Columbia, 2021

You might want to reference the most obvious form of this dependency, the student debt many accrue to finance the expensive degrees that qualify one for a PhD at a prestigious university (at Columbia, master’s degrees go for around $120k in tuition alone). And at last, you might want to talk about the future and describe how chances have increased dramatically that the precarity experienced during a PhD program will not be alleviated by the job market. In fact, roughly 80 percent of all instructional appointments in higher education are now accounted for by precarious adjunct faculty positions instead of stable and health-insured tenured faculty.

And because Worker B is skeptical already, you might want to stay away from jargon and abstractions, which are always easier to refute than the stickiness of experience. So, rather than theorizing the contradictions between capital and labor or class interests, you will consider mentioning a recent article by Edward Nik-Khah in which he describes one of the leading architects of this two-tier system in academia, George Stigler. [1] Witnessing the student protests in California in the wake of 1968, this pioneer of neoliberalism and close colleague of Milton Friedman came up with a two-point program in the 1970s in order to prevent these protests from ever happening again, as Nik-Khah recounts. First, the student needs to be turned into a consumer; this is accomplished by the university drastically increasing tuition, making the student financially dependent on their family or some other organization. Second, instructional services need to be partitioned into a two-tier system, wherein a small group of secure and stable jobs for research faculty is flanked by a large group of itinerant workers. Since interfacing with students is supposed to be largely delegated to the precarious second group, teaching is supposed to be dictated more easily by market demand, and the (now-tenured) faculty is also supposed to be alienated from students, preventing any solidarity between the two groups.

How you want to combine and mix these stories, facts, and arguments largely depends on Worker B. But as you compose them, over and over, you will come to realize the pattern, the three or four different things they might say, and slowly build your organizing repertoire around them.

Columbia-University-Streik / strike, New York, 2021

In my case, I developed this repertoire when I was dispatched from organizing my own department, Art History and Archaeology, to organize Columbia’s School of the Visual Arts (SVA) and its master of fine arts students. This was because our department seemed rather well prepared for a strike, whereas the 120 graduate workers at SVA had a unionization rate well below 10 percent and, as far as we could tell, strike commitments somewhere between 0 and 1 percent. So, I spent a few days walking through the two buildings where they have their studios, knocking on doors, hoping that someone was there to get them to sign a union card and commit to the strike. By the time Columbia’s administration responded to our endeavor by barring non-MFA students from entering the SVA buildings, my fellow organizers and I had achieved a unionization rate of roughly 50 percent, with each conversation taking 10 to 20 minutes. The administration’s response, however, proved to be successful: our efforts to organize the MFA students largely collapsed because we were unable to get people to commit to more than just signing union cards – no organizing their fellow workers, no joining the strike – ultimately turning SVA into one of the departments with the lowest strike rates at the entire university.

The question that kept haunting me over the past few weeks was how to make sense of this failure. Why does Worker B’s resistance seem to be exceptionally high among MFAs in particular? Immediately, a variety of commonplace factors come to mind that would sketch an explanation through the art sector’s mode of production: the self being the basic currency-determining value; intense competition and stratification, with the (blue-chip) winner taking all; immense financial pressure to succeed because of (student) debt. But all these conditions can be found in other sectors as well, especially in academia, and the differences are at most marginal, not categorical.

There was one point, however, that kept coming up while trying to turn MFA graduate workers into department organizers that went beyond the conditions of production. It was repeatedly indicated that it made them “uncomfortable to make others uncomfortable.” I’m not sure that there is any other sector where the 1970s slogan of the “personal is political” has been as systematically interpreted into an orthodoxy of self-care. This understanding ultimately leans much more into the privatization of politics than into the politicization of the private sphere that it was initially about, something Olúfémi O. Táíwò has recently identified as the problem of standpoint epistemology. [2] As one’s own subject position is transfigured into something that is both singular and divided from others by an unbridgeable gap, ethical meditations have come to stand in for political work tout court.

Columbia-University-Streik / strike, New York, 2021

I can’t help but wonder, What would have happened to these ethics of the individual if these students had repeatedly clashed with Worker B? Would these encounters have clarified that there is nothing singular about exploitation, that it standardizes and homogenizes in order to create patterns and categories? Would it have become clear that the divisions of difference might be much less a progressive accomplishment than one of the most basic tools of managerial domination (e.g., the leaked emails by Amazon executives revealing how workplace diversity has been employed to prevent workers from unionizing)?

Revising the legacies of the 1970s and that era’s understandings of what political work involves is long overdue. Rather than withdrawing into the comfort of private meditations, it is time to think of political work as a way to get rid of your self – to tear down the barriers and divisions instituted to separate you from your colleagues. Just like in Sander’s and Fassbinder’s depictions of industrial sabotage or Sokhona’s staging of a rent strike, the collectivity necessary to fight management, maintain solidarity, and actually organize structural change relies on an expression that is more about sameness than about difference, a story that embeds experiences in the overarching social forces they are shaped by, a point of view that is simultaneously larger and more microscopic than allowed for by the ethics of the individual. Maybe, then, working through these legacies entails the chance of discovering new channels to square the modernist circle, of composing forms that don’t shy away from the discomforts of (political) content.

Pujan Karambeigi is a PhD student in art history at Columbia University, with a focus on how artists and cultural workers from West Africa and the Middle East relayed the collapse of the so-called guest worker system in Western Europe in the 1970s. He is an editorial contributor at Jacobin Magazine and regularly writes cultural criticism.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Deutsche Kinemathek; 2. © Universal Pictures, courtesy of Schrader Productions and British Film Institute; 3. Courtesy of Caroline Smith and Student Workers of Columbia; 4/5. Photos: Madison Ogletree

Notes

| [1] | Edward Nik-Khah, “On Skinning a Cat: George Stigler on the Marketplace of Ideas,” in Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, eds. Dieter Plehwe, Quinn Slobodian, and Philip Mirowski (London: Verso, 2020), 46–68. |

| [2] | Olúfémi O. Táíwò, “Being-in-the-Room Privilege: Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference,” in The Philosopher 108, no. 4 (Autumn 2020): 61–79. |