WELCOME TO THE RESORT Six Theses on the Latest Structural Transformation of the Artistic Field and Its Consequences for Value Formation

John Miller, „Semblance“, 2013

Thesis 1

The art world has seen the emergence of specifically constituted resorts, both online and offline, where artistic production is abstracted from and art is assessed on the basis of quantitative criteria.

The first signs of the latest structural transformation of the artistic field – and by structural transformation I mean lasting changes to economic and social infrastructures – were apparent even before the onset of the global pandemic. A key element of this transformation, I believe, is the relocation of many art-world interactions to the online sphere. Although this shift had commenced before the Covid-19 crisis, the pandemic accelerated and intensified it – for example, by fueling the rapid proliferation of so-called online showrooms. What interests me most about this shift are the consequences for the processes of value formation on the sides of both the production and the reception of art when art-world activities increasingly occur online. My perspective is that of a participant observer who, far from standing outside the sphere of value, examines its changing ways from a position of implicated distance. I see the art business’s digital venues – Instagram first and foremost – as “resorts” of a sort, though social media are obviously more accessible than the gated community of a resort hotel. Analog resorts are emblematic of the exclusion of all those who cannot afford the trip or the stay; social media, by contrast, are in principle open to everyone with an internet connection. [1] Still, the denizens of Instagram likewise live in a resort-like bubble in which digital connectedness is mistaken for social relationships. [2] No longer exposed to the physical presence of others, they can act largely unconstrained by the complexities of their lifeworlds. Indeed, it is my observation that artists, critics, and curators present themselves online in ways that don’t allow one to draw conclusions regarding the realities (and difficulties) of their life and labor. That is to say, the price to be paid for visibility on this platform is the invisibility of those social contexts in which works of art are embedded. It becomes difficult or even impossible to understand what is historically at stake in a particular artwork (which is not to say that the latter’s significance is ever entirely bound up with those contexts). For it is only through an approximative reconstruction of those contexts that we are able to grasp what a work is trying to propose or suggest. The problem is that these formative contextual conditions are difficult to convey online, and so they fall away. The online showrooms’ so-called editorial formats are no more suitable as a forum for this purpose – they tend to function like press releases and serve publicity purposes.

This abstraction on Instagram or in the digital showrooms from the conditions in which artists work also alters the parameters of value formation and attribution. For if the historical stakes of a piece of art cannot be understood without reference to the social context of the work of making it, these digital platforms cannot accommodate an adequate critical reception. The polarizing structure of social media, it seems to me, likewise makes them hardly a welcoming environment for critique. When websites such as Facebook let the user choose only between “like” and “not like” – perhaps with the additional option of leaving a comment in a thread – nuanced debate is hard to come by. [3] Moreover, such rapid evaluation results in a “quantification” of art; [4] in other words, it gives rise to the impression that the relevance of a work can be gauged by the number of likes or by how many followers its creator has. The transmutation of art into a measurable quantity is something we are familiar with only from the sphere of auctions, where a work’s putative value is expressed by the price it fetches. And so, just as price rules as the gauge of value in the auction sphere, the measure of creative success in the online domain is quantitative and not grounded in a substantive argument.

The situation was different as recently as the 1990s, when the market value of a work of art sold at auction typically derived from a symbolic value engendered elsewhere, by the consensus or dissensus of critics, art historians, curators, and the artist’s peers. [5] Nowadays, by contrast, market values appear to be primarily driven by the question of whether a work promises short-term speculative gains, as the agent Lisa Schiff has recently observed with some regret. [6] Schiff – who, it is worth noting, works as an art advisor – aptly speaks of a “new mode of value production” in which the objects themselves, their aesthetic, historical, and/or political stakes, no longer play any role. All that matters today, she argues, are the “financial gains” that a prospective buyer hopes a work will generate. The ideal of an artwork totally removed from the market and defined by its “true essence, power, and ability to inspire” that Schiff invokes in sketching this history of decline is of course problematic. Yet despite her unbroken faith in the truly inspiring essence of art, her diagnosis of a new value regime is largely correct. We are indeed witnessing the beginning of a shift in the dynamic interplay between symbolic and market values in which market value seems to be gaining the upper hand. It would have been illuminating, though, if Schiff had made more of an effort to examine her own role in these changed processes of value attribution.

Hauser & Wirth Menorca

Thesis 2

The resort-like bubbles on Instagram aside, the analog art world, too, has seen the emergence of numerous luxury art resorts that, merely by virtue of their social homogeneity, are the antithesis of the prevailing emphasis on diversity.

But when I speak of “resortization,” I am also alluding to a second trend toward – this time literal – resorts that has been apparent in the analog art world for a few years. I am referring to the phenomenon of several mega-galleries opening branches in the luxury resort towns frequented by the rich – places like Aspen, the Hamptons, or Monaco. [7] The resort gallery in the luxury enclave is not an altogether novel phenomenon – see, for example, the gallery Vito Schnabel established in Saint Moritz in 2015. Until recently, however, these galleries tended to play a subordinate role in the global market dynamic. This is changing right now, with major art-world players such as Hauser & Wirth opening branches in luxury resorts – most recently, Menorca. A short fly-through video released on Hauser & Wirth’s Instagram account gives the viewer an idea of the sprawling finca-style hotel complex on the Spanish island in the Mediterranean. It abuts the sea and features outdoor sculptures including one of Louise Bourgeois’s monumental Spiders as well as a country-style cantina under the open sky. True to the resort concept, the installation caters to the art collectors’ culinary as well as aesthetic needs. In other cases, the arrival of the art business turns places one ordinarily would not have suspected of drawing the jet set into potential luxury enclaves. Consider the Scottish village of Braemar, where Iwan and Manuela Wirth opened an exquisite hotel called The Fife Arms in 2018 that houses both their own collection and works of art commissioned for the site. Another community that has gone through a kind of luxury upgrade is the small town of Arles in France, which now boasts the collector Maja Hoffmann’s private museum LUMA and numerous guesthouses Hoffmann has transformed into luxury hotels. One of them, the L’Arlatan, beckons with a complete set of interiors designed by Jorge Pardo, from the artist’s signature lamps and colored floor tiles to the polychromatic patterns of the bedsheets. Both Arles and Braemar, one might say, have been given a radical makeover initiated by gallery owners and/or private collectors that has bumped them up into the rarefied class of global luxury destinations.

Yet I would be remiss at this point not to mention the contrary developments in the artistic field that are occurring concurrently with this form of resortization. The trend toward art in resorts and art as a resort outlined above is offset by the efforts of a growing number of art institutions and galleries – prompted in part by protest movements like Black Lives Matter – to diversify their programming and integrate more non-Western practices and discourses. Numerous Western European museums have also initiated a long-overdue revision of the Western canon and are reconceiving their collections in a postcolonial perspective. [8] The decentering of art and art history has become a key concern in the world of biennials, manifestas, and documentas as well, as exemplified by this year’s Documenta 15 and its focus on collectivist-activist practices designed to largely circumvent the laws of the Western art market.

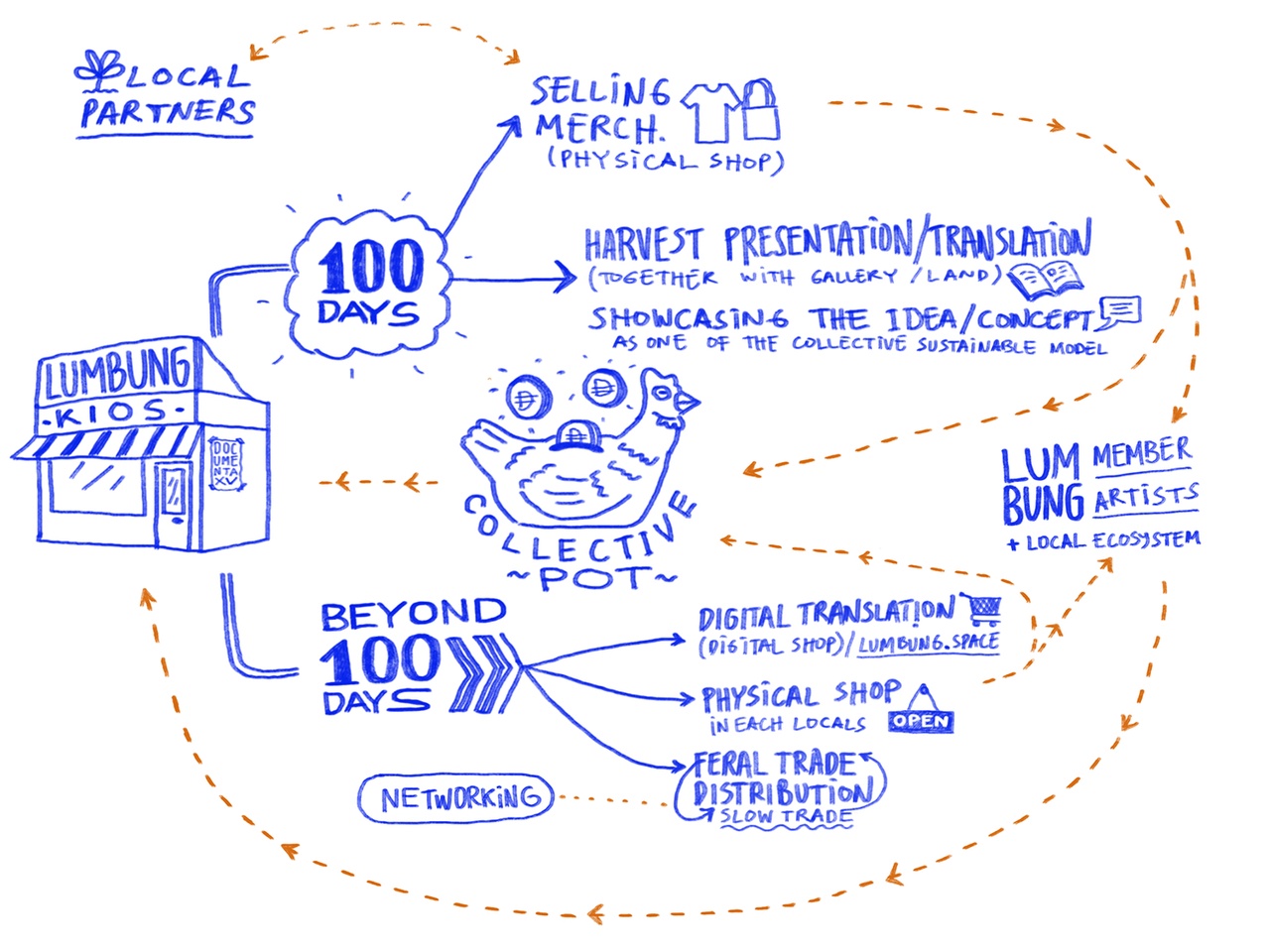

lumbung Kios, Harvest von / of Angga Cipta, 2022

But: by drawing critics’ attention, these welcome overtures and revisions have allowed another ongoing reorganization of the art economy to go unnoticed whose effect is the very opposite of diversity and decentering – it results in the exclusion of minorities and the consolidation of social homogeneity, the enforcement of conservative agendas, and the perpetuation of the principle of white supremacy, which is still deeply entrenched in parts of the art world. In other words, the growing political awareness in the art field and its progressive reorientation have oddly gone hand in hand with developments that have prepared the ground for a conservative backlash. [9] We might even go so far as to say that the emphasis on “learning and sharing” at this year’s Documenta is not just a response – one that makes good sense – to today’s crises and eroding social systems. Its proposal of a different and more communitarian economy, it seems to me, is also the flip side of the art world’s transformation into a big business, with galleries as gigantic media enterprises. Both developments appear to be independent of each other but are actually intimately connected.

Let me not be misunderstood: obviously, there have long been manifold intersections between the “political biennial art” and “gallery art” segments, as illustrated by the instances in which collectors or galleries have covered the production expenses for works shown at the Venice Biennale. Ventures such as the Zwirner empire’s branch 52 Walker in New York, which, under Ebony L. Haynes’s leadership, exclusively shows Black artists, likewise demonstrate that the market’s agents find ways to capitalize on the diversity imperative. My point is that we need to pay more attention to the ongoing restructuring – both online and offline – of the art economy, which cannot but affect progressive agendas as well.

The last time we witnessed a comparable simultaneity of disparate tendencies was in the 1990s, when the rise of multiculturalism and identity politics occurred in tandem with a reorganization of the art economy: a West-centric art world in which the retail dealer was the prevailing business model was transformed into a global visual industry dominated by corporate mega-galleries. [10]

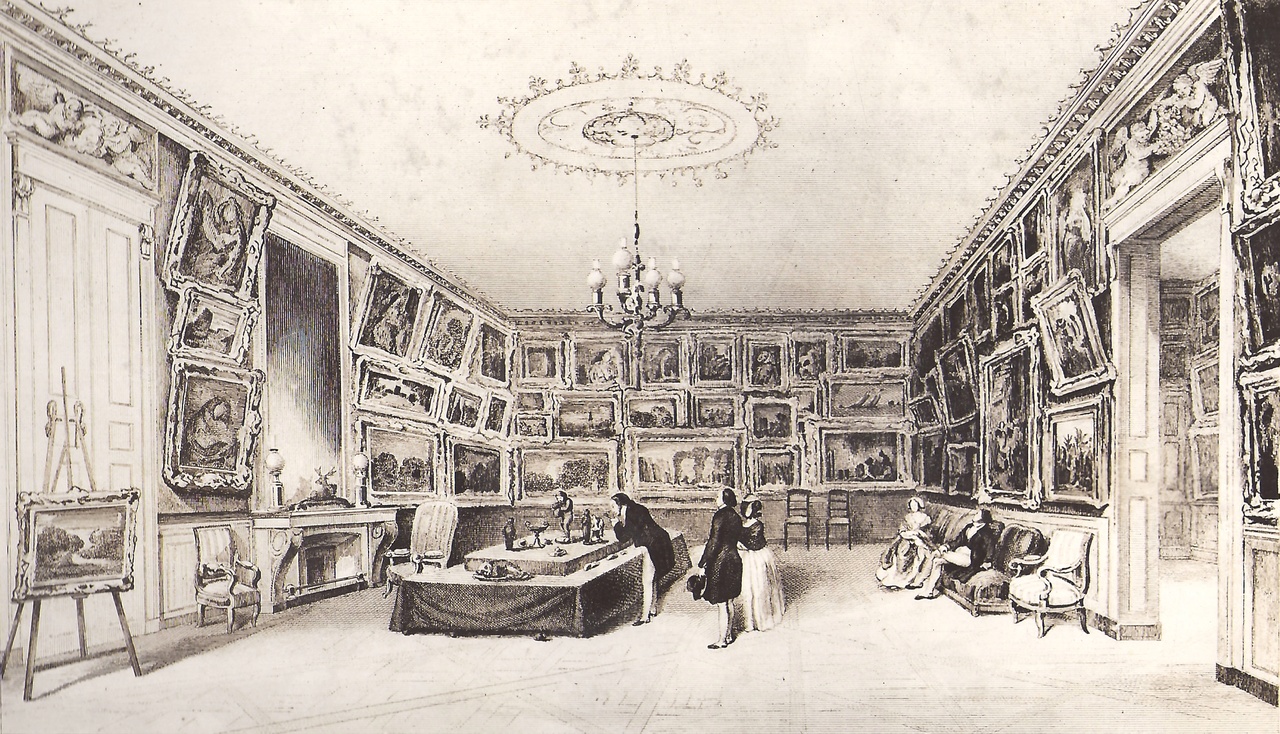

Charles-François Daubigny, „Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris“, 1845

Thesis 3

In a value-theoretical perspective, too, the art world’s resortization represents a profound shift, especially because it implies that some actors who used to play an important role in value formation find their significance diminished.

The emergence of elite resorts in the art field has far-reaching consequences also for the theory of value, as the history of the origins of Western Europe’s galleries illustrates. In the 19th century, galleries such as the Durand-Ruel (1834–1974) were established in cities like Paris in no small measure because those cities were also where the other agents involved in value formation (artists, critics, and art institutions) resided. That is to say, since the late 19th century, art dealers have seen the exchange of ideas with other agents in the field as being at least as important for their own efforts to build up the symbolic and market value of the art they represent as the close contact with affluent collectors. Lately, however, these priorities appear to have shifted, especially in the art trade’s blue-chip segment: physical proximity to wealthy clients is now seen as crucial to the business – and that is exactly what the resort offers. Just as critique has no real place in the Instagram bubbles, critics, traditionally an opinionated bunch, would only complicate things at the resort. I will only note in passing that the freeports that have recently become a big talking point are in a sense precursors of the resort: not unlike the latter, these art storage facilities that have sprung up around airports like Geneva’s are difficult to access. [11] Works of art are stored and traded in tax-free deals behind closed doors (away from the eyes of the art public). The freeports, it seems, put the “private viewing,” a format that has caught on more widely since the pandemic, into practice on a larger scale and establish it as the standard mode of engagement with art – one that is likewise exclusive and reserved for select clients. All others – everyone who is not a member of the global moneyed elite – never know the first thing about it.

But the luxury art resort takes things even further than the private viewing and the freeport by featuring the amenities that let the dealers and their clients, who often arrive by private jet, celebrate a certain lifestyle in an exclusive setting. The time they spend together at the resort, needless to say, is put to good use on confidence- and value-building measures. The philosopher Martin Hartmann has argued that people are most apt to trust one another when they are at home “in the same institutional regime.” [12] In other words, outsiders who come from a different class background and/or have less money and lack the expected urbaneness are less likely to gain their trust. The resort’s social homogeneity, where the wealthy are surrounded by their own kind, thus prevents interactions within it from being contaminated by distrust. More so, social inequality and poverty are invisible inside the resort, promising frictionless transactions. All disturbing factors that might jeopardize the art deal are eliminated. [13] The participants meet each other in a relaxed atmosphere, as though they were on vacation. And that, of course, puts people in a spending mood, so that business is bound to be brisk at the resort.

Geneva Freeports, 2016

Thesis 4

The resortization of the art world precipitates a new structural transformation of the public sphere that affects our conception of art.

I recently visited Monaco to take a look at Hauser & Wirth’s gallery branch and Galerie Johann König’s showroom there. In both cases, the premises felt oddly deserted, as though awaiting the arrival of an art scene that could not possibly be at home in Monaco, given the exorbitant cost of living. What also struck me as unpleasant about Monaco is that the tiny city-state – which has a well-deserved reputation as an oasis for tax dodgers – provides virtually no public spaces such as parks or plazas for its residents. Every square foot is built up with tightly packed luxury apartment tower blocks, with the remaining space reserved for construction cranes and expressways. The main public attraction at the heart of this dystopia is the famous Casino de Monte-Carlo, where spectators gather outside to watch the Ferraris being parked.

Monaco, it seems to me, has taken the “privatization of the public sphere” – a tendency first observed by urbanists in the 1990s – further than most places: luxury real estate and luxury stores aggressively monopolize the public space. If you are not a millionaire, there is no room for you in this town.

Such luxury enclaves are obviously a far cry from the Habermasian ideal of a functioning public sphere sustained by social safety nets. [14] True, the old “critical public” that Jürgen Habermas favored in the 1960s was for its part integrated into a problematic construct, that of the nation-state. And it was steeped in colonial thinking and heteronormative premises. Yet despite its deficits and exclusions, this public at least represented a framework within which its flaws could be discussed and might in principle have been remedied. By contrast, resorts like Monaco strike me as paradigmatic examples of a new structural transformation – in particular of the art public – in whose wake globally dominant gallery corporations take charge of the process of value formation, to the exclusion of many other actors who have hitherto been involved in it. The resort effectively implements the same devitalization of public discussion and critical engagement that we already observed during the pandemic-era lockdowns. When openings were canceled, so were social interactions, and hate speech and mobbing increasingly ruled the day on the internet (which is not to say that positive experiences of community life do not also exist online). This forestalled substantive debate over the relevance of artistic practices, which compromised their credibility and hence also the basis of their value. Yet the rise of art-world practices that largely dispense with debate also hint at the possibility that the processes of value formation may in the future no longer have any need for such discourses.

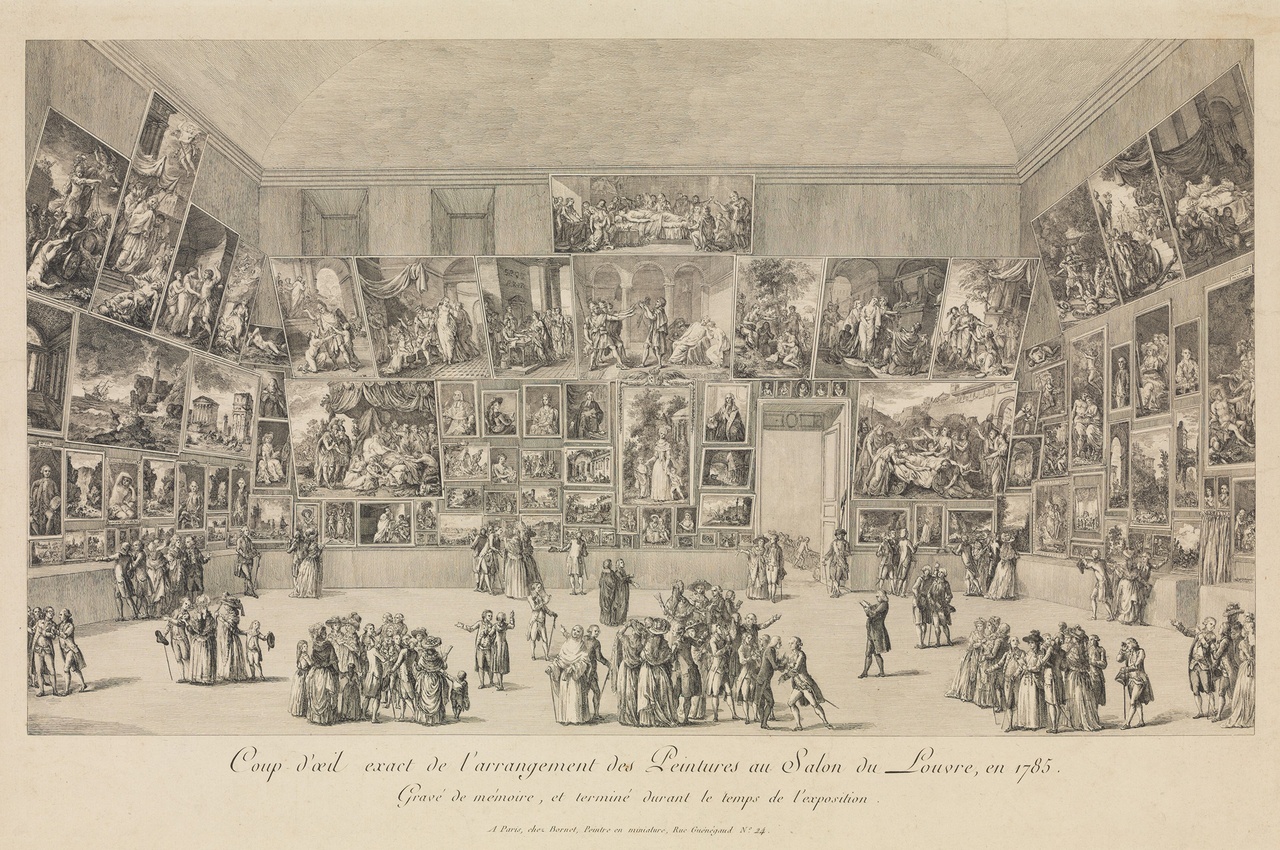

Compared to the homogeneous and consistently socially privileged public of the resort, the traditional art public that came together in the 18th century looks positively hybrid and pluralistic. Thomas Crow has argued that the first salons in Paris attracted a distinctly heterogeneous audience that was defined by a certain social mobility. [15] Nothing remains of this plurality at the resort, where the members of the “global class of asset owners” dominate, in whose hands wealth is now accumulating. [16] If we also consider the fact that the idea of “modern art” has historically been directly bound up with the ideal of its public accessibility, it becomes clear that the art world’s resortization cannot but have an impact on our conception of art. Given that the public at the luxury resort consists exclusively of affluent people, we might well ask whether the object of such an economy is even still art in the modern sense. Or do we need to find another name for what is presented and traded there?

Pietro Antonio Martini, „Salon de Paris“, 1785

According to Crow, the audience of the earliest salons in the 18th century was set apart by its eagerness to engage in discussion and its zeal to assess what it saw. This audience, he writes, was transformed into a veritable public only at the moment it justified and set value on artistic practices. [17] The development of an art public thus hinges on its ability to pass well-founded value judgments. Conversely, an audience that is no longer capable of explaining why it sets value on some works is incapable of constituting a public. Not unlike the digital platforms, the resorts would appear to be “competing publics” in which quantitative criteria are paramount. [18] On social media, it is the number of likes and followers that establishes value; at the resort, meanwhile, the “fictional expectations” of future increases of market value are decisive. [19] Either way, it seems to me that in both spheres, on Instagram and at the luxury resort, the symbolic value that other market actors negotiate elsewhere is increasingly peripheral.

Thesis 5

If you are not on Instagram, you may be forgotten.

Hardly anyone in today’s art world resolves to go completely offline, even as almost everyone takes a critical view of the platform companies’ machinations. To my mind, that is because of the risks that come with digital abstinence. [20] Art producers, especially ones who are only beginning to build their careers, do well to promote themselves on Instagram, lest they run the risk of not existing in the eyes of the other users – which is to say, pretty much everyone in the art world. Their work might vanish from the art world’s collective memory and garner no attention and appreciation at all. Since the onset of the pandemic, opportunities to see and be seen at openings or other events were few and far between; so many actors in the field have shifted the focus of their activities to social media, where they now post incessantly. In this way, they make the platform companies’ dream of “excessive users” a reality, a fact that I think users (myself included) hardly consider. [21] Perhaps voluntary submission to a most questionable corporation’s demands strikes them as the lesser evil in comparison to the danger of being forgotten. As Rambatan and Johanssen note, Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal has led to a kind of detachment from the platform among users. [22] Yet despite this alienation, they post like there is no tomorrow.

Another conspicuous aspect of artists’ online presentations is that they earn significantly more likes when they pose with their works. What I have described elsewhere as the personalization of anything and everything in celebrity culture has evidently been boosted to a new level by social media. [23] During this year’s Venice Biennale, for example, numerous galleries posted photographs of “their” artists standing next to their works at the show, satisfied grins on their faces. The fact aside that these staged shots served the galleries to skim off the surplus value generated by their participation in the exposition, they also added to the credibility of the works on view, visibly tying them to a singular originator whose presence demonstratively attested to their status as unique objects – and that is what makes them a commodity of a special kind in the first place. As on other occasions, however, the downside of this visibility is that the artists, by appearing on Instagram with their creations, effectively present themselves as products available for consumption. [24] Again, people presumably think that the risks of invisibility outweigh the danger of being consumed. Plus, the penchant for self-staging is not a novel phenomenon in the art world – just think of Dalí and Warhol, two pioneers of the deft use of media for self-promotion. But these artists faced a nascent media society and were able to stake out their positions vis-à-vis its mechanisms; today’s artists, by contrast, are dependent on Instagram, which is to say, on the goodwill of a dominant global corporation and its algorithm. Then again, smartly advertising one’s own products and staging them on Instagram can also be part of the artist’s (or critic’s) work, as I know from personal experience.

Another factor that makes social media especially appealing to art-world actors is the ability to generate attention and appreciation while circumventing the traditional gatekeepers and authorities that confer recognition on artists. [25] The fact that social media are more permeable than traditional art institutions, their operations less defined by gatekeeping, selection, and exclusion, is what arguably makes them drivers of the diversification that is rightly called for today. They allow voices from beyond the often-invoked Global North to be heard. And while participation in the analog art world’s social functions requires the completion of exhausting and sometimes humiliating initiation rituals, the internet accommodates manifold projections of self and allows for the coalescence of communities that would encounter resistance and/or be subject to discrimination away from the screen. [26] Social media’s capacity for emancipatory-transgressive practices, that is to say, is real, but its flip side is that users surrender their data to a platform company that squeezes profit from them and, what is worse, is a powerful contributor to efforts to undermine the rules and institutions of the democratic order. [27] Even early apologists of the internet, such as Geert Lovink, now point out that little is left of its original emancipatory promise. [28] The reality is that social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook have built a thoroughly regulated sphere in which economic pressures trump all other considerations – a sphere that resembles the resort.

KÖNIG MONACO Showroom, Villa Nuvola

Thesis 6

The art world’s resortization is closely related to the financialization of the economy at large, in that both abstract from production.

The new art world resorts currently being established both online (in the form of Instagram bubbles) and offline (in places like Monaco, Menorca, Aspen, etc.) are directly connected to developments on the macro level that are commonly described as the “financialization” of the economy. [29] Financialization means that profits are generated irrespective of productive activities and increasingly through financial channels – which is to say, they are based on an abstraction from production. [30] Although, as Jamie Merchant writes, corporations still try to squeeze extra work out of their employees while paying them the lowest possible wages, these conflicts over the organization of labor and working time largely do not affect the processes of financialization. In a financialized economy, wealth accumulates on the basis not of labor but of “revenue-generating assets” (Merchant), leaving all those behind who work for wages or fees. [31] Social inequality in the asset economy results from the fact that only asset owners achieve affluence, with their wealth rising faster than inflation or wages. And that class, needless to say, also includes art collectors, since ownership of a work ideally promises increases of market value far in excess of the returns to labor.

Then again, one might also argue that the global class of asset owners is interested in owning works of art because they are assets, as identified by their speculative potential for appreciation, but not assets pure and simple. Unlike other assets, works of art have not altogether severed the ties to the sphere of their production – on the contrary: the unique material work in particular is capable of suggesting that the creative labor expended on it is somehow stored up within it. We might accordingly say that works of art bring into play – with greater or lesser immediacy – the reality of labor that is repressed in a financialized economy. That is true even of immaterial non-fungible tokens (NFTs), whose very name indicates that they are meant to be incapable of being exchanged or replaced. The NFT’s assertion of originality emulates the uniqueness of the work of art. As with the latter, the imputation of value is also shored up by a reference to its singular creator.

And since both NFTs and other art and media forms owe their existence to an individual author and her specific artistic labor, they imply a residual reference to labor that financial products have long dissociated themselves from. Considered from this vantage point, works of art are attractive to asset owners for two reasons: one, because they promise a speculative appreciation that exceeds the returns from labor, and two, because they invoke the reality of labor that is repressed in a financialized economy. Even better, they (visibly or latently) bring realities of labor into play without the attendant nuisances to the wealthy (such as strikes or demands for higher wages).

Shl0ms, „$CAR“, 2022, Videostill

Yet if the worlds of finance and art structurally resemble each other ever more closely, it is because they share an increasing focus on the processes of distribution, be it in the stock market or the sphere of auctions. In analogy with the monopolistic formations that distinguish digital capitalism, the commercial art world (and art resorts in particular) is ruled by a “very small number of very large corporations” that control “access to goods, services, and infrastructure.” [32] Indeed, very few mega-players dominate the art resorts and determine inclusions and exclusions. Drawing on the terminology developed by the sociologist Philipp Staab, we might characterize art resorts like Hauser & Wirth Menorca as “proprietary marketplaces” in the mold of Amazon: as with Amazon, market-making and market access are key. The owner of the marketplace has the power to admit other market participants and set their own commission. If the luxury resorts of the art world appear to resemble the digital sphere’s proprietary marketplaces, it is hardly surprising that the art world has also seen the emergence of proprietary online marketplaces modeled on Amazon, such as the Zwirner gallery empire’s Platform, which presents and sells works offered by twelve smaller New York galleries. Zwirner gives his junior colleagues access to his distribution system and client base and, in return, receives a commission for the sales he brokers. The venture is a win-win for Zwirner because it also brings in fresh art and contacts for the gallery.

Still, online galleries like Zwirner’s Platform should not be seen as proprietary marketplaces pure and simple. The bond between them and the works of their artists is too strong – they are dependent on a steady supply of the art commodities they sell. It seems, though, that the emphasis is more and more on the “efficient distribution of the goods being manufactured,” and that is where both online and offline resorts are unrivaled. [33] The producers, by contrast – whether they are purveyors of art or critique – increasingly seem to play only a subordinate role in this sphere of distribution. Though here, too, a hierarchical distinction exists: artists with a proven record of market success are welcomed as the producers of the raw material on which the art resort runs and as personified guarantors of their product’s value form; even more, they function inside the resort as proxies for the conditions of production that are otherwise repressed here. As for the critics, their flanking production of significance has certainly lost cachet at the resort, although some of them are still allowed in as guests as long as they follow up with glowing reports on Instagram – the collector Dakis Joannou’s events on the island of Hydra being characteristic occasions for such reporting.

In light of these developments, we may wonder, of course, what it means for “art” as such when it increasingly circulates between digital bubbles and luxury resorts. What are the implications for the process of value generation when the influence of art-world actors who used to play a part in setting it wanes within the resort? And how does the ascendancy of quantitative criteria (like the number of likes and followers or market prices) in conjunction with the decline of contextual knowledge affect what is considered valuable? I recently talked to a few critic friends about the new value regime established by the art world’s resortization. We asked ourselves whether artistic production might need to respond to the lack of public audiences and nuanced criticism at the resort by dialing up its internal discursiveness, effectively taking the production of its significance and contexts into its own hands. Given the growing structural resemblance between assets and works of art, we posed the question of whether artists might not do well to put greater emphasis on the difference their works make under the condition of convergence. We came to the conclusion that the current reorganization of the economy of art requires both artists and critics to rethink all their presuppositions, tools, and procedures. Such a reset, needless to say, cannot be instantaneous; it takes time. For now, we can only try to keep analyzing the latest structural transformation of the art world in all its facets. This may also be fertile ground for a critique that finds itself weakened in the resort: by keeping an eye on the current tendencies toward resortization in the various segments of the art world, critique might stand its ground and demonstrate that it has more to offer than rapid-fire evaluations or apologetic discursive embellishments.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of Texte zur Kunst and teaches art history and theory at the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications are In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and Vom Nutzen der Freundschaft (The Uses of Friendship) (Spector Books, 2022).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of the artist and Meyer Riegger Berlin, Karlsruhe, Basel; 2. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth, photo Daniel Schäfer; 3. Courtesy of documenta fifteen; 4. © Durand-Ruel & Cie., courtesy of Archives Durand-Ruel; 4. Fred Merz | Lundi13; 6. A. Hyatt Mayor Purchase Fund, Marjorie Phelps Starr Bequest, 2009; 7. Courtesy of KÖNIG GALERIE Berlin, Seoul, Vienna, photo Christoph Philadelphia; 8. Courtesy of the artists

Notes

| [1] | Unless they live in countries like Russia, where the authorities recently blocked Facebook and Instagram. |

| [2] | See “Das Unbehagen ist ein erster Ansatzpunkt,” interview with the sociologist and social psychologist Vera King on the occasion of the symposium “Das vermessene Leben,” Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, July 1, 2022. |

| [3] | Then again, one might also consider “likes” the equivalent of peer recommendations in the analog sphere, which are of considerable significance in processes of value formation and recognition. Yet even if we regard them as essentially recommendations in digital garb, they do not allow for the differentiated supporting arguments that accompany the analog original. In other words, if “likes” alone determine whether my stock rises or falls, the substantial stakes of my work fade from view. |

| [4] | Steffen Mau, Das metrische Wir. Über die Quantifizierung des Sozialen (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2017). |

| [5] | Isabelle Graw, “Symbolic Value, or: The Price of the Priceless,” in High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (Berlin: Sternberg, 2009), 27–31. |

| [6] | Lisa Schiff, “As an Art Advisor, I’ve Watched ‘Meme Art’ Destroy All Logic in the Art Market. Here’s What We Can Do About It,” Artnet News, June 15, 2022. |

| [7] | These two pandemic-related “structural changes” – the expansion of the online market and investments in “physical gallery space, including in second-home locations such as the Hamptons, Aspen and Menorca,” are also the subject of an article in Melanie Gerlis’s “Collecting Updates” column for the FT; see her “Art Galleries Stage Strong Post-Covid Recovery, Art Basel–UBS Report Finds,” Financial Times, online edition, September 9, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/79358b90-8c71-4242-b583-2fd192366746 (behind a paywall). |

| [8] | Meanwhile, the privatization of museums is moving forward in Germany as elsewhere; economic pressures force them to cooperate with private collectors, and sometimes they also appear as market participants in the auction sphere. Museums are manifestly not immune to the effects of resortization. |

| [9] | As Ben Davis points out in a recent interview with Ben Koditschek, the art market’s transformation into a big business coincided with the nonprofit sphere’s growing commitment to “institutional critique, community-based art, and questions about representation.” I think his contention that the politicization of the art world also serves a compensatory role is not without merit. See Ben Koditschek, “The Relationship Between Art and Politics Is Shifting: An Interview with Ben Davis,” Jacobin, online edition, June 27, 2022. |

| [10] | Isabelle Graw, “The Art World as an ‘Industry Engaged in Producing Visuality and Meaning,’” in Graw, High Price, 147–48. |

| [11] | See also the ARTE documentary Schätze unter Verschluss – Das System Freeport, 2021. |

| [12] | Martin Hartmann, Die Praxis des Vertrauens (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2011), 467. |

| [13] | The HBO series The White Lotus vividly illustrates how class conflicts, exoticization, and racist discrimination are perpetuated at a resort. In the show, these phenomena manifest most distinctly in the form of clashes between the (white) patrons and the hotel staff, who are often people of color. The resort is portrayed as a zone that, far from being spared social conflict, condenses social antagonisms as though in a prism. |

| [14] | Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger and Frederick Lawrence (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989). Originally published in German in 1962. |

| [15] | Thomas E. Crow, “The Salon brought together a crude mix of classes and social types,” in Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 1–22, here 1. |

| [16] | Jamie Merchant, “Endgame: Finance and the Close of the Market System,” Brooklyn Rail, March 2022. |

| [17] | See Crow, Painters and Public Life, 5: “But what transforms that audience into a public, that is, a commonality with a legitimate role to play in justifying artistic practice and setting value on the products of this practice?” |

| [18] | Jürgen Habermas, “Überlegungen und Hypothesen zu einem erneuten Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit,” in “Ein neuer Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit,” ed. Martin Seeliger and Sebastian Sevignani, special issue, Leviathan 37 (2021): 470–500. |

| [19] | Jens Beckert, Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). |

| [20] | The following considerations benefited enormously from my exchange with Merlin Carpenter, who made the decision not to be on Instagram or Facebook. For a critique of platform companies, see Joseph Vogl, Capital and Ressentiment: A Brief Theory of the Present, trans. Neil Solomon (Medford, MA: Polity, forthcoming); Philipp Staab, Digitaler Kapitalismus. Markt und Herrschaft in der Ökonomie der Unknappheit (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2021); and Urs Stäheli, Soziologie der Entnetzung (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2021). |

| [21] | Bonni Rambatan and Jacob Johanssen, “Networks and Psyches: Unleashed and Restrained,” in Event Horizon: Sexuality, Politics, Online Culture, and the Limits of Capitalism (Winchester: Zero, 2021), 36. |

| [22] | Ibid. |

| [23] | Isabelle Graw, “Market-Reflexive Gestures in Celebrity Culture,” in Graw, High Price, 156–226. |

| [24] | Rambatan and Johanssen, Event Horizon, 8. |

| [25] | Many observers have noted that the power of gatekeepers and experts is diminished online. I believe this effect has advantages as well as disadvantages. On the one hand, no one needs to wait today for someone to open the door for them so they can publish something. Anyone can present their thoughts to others for their consideration. On the other hand, Habermas rightly remarks that authorship is something that needs to be learned. Once the filters of editors and publishers are absent, online publishing allows for the dissemination of unhinged hate speech, conspiracy theories, and a flood of fake news, as we have all become aware. See also Habermas, “Überlegungen und Hypothesen.” |

| [26] | See Legacy Russell’s observations in conversation with me: “Bodies That Glitch: A Conversation Between Legacy Russell and Isabelle Graw,” Texte zur Kunst, online edition, December 23, 2020. |

| [27] | On the problem of platform companies’ weakening the legal order, see also Vogl, Capital and Ressentiment. |

| [28] | Rambatan and Johanssen, Event Horizon, 36. |

| [29] | Greta Krippner, “The Financialization of the American Economy,” Socio-Economic Review 3 (May 2005): 173–208. |

| [30] | Merchant, “Endgame: Finance and the Close of the Market System.” |

| [31] | Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings, The Asset Economy: Property Ownership and the New Logic of Inequality (Oxford: Polity, 2020). |

| [32] | Staab, Digitaler Kapitalismus, 20. |

| [33] | Ibid., 45. |