HOW MUCH PERSON IS IN THE PRODUCT? On the Metonymic Interrelation between Works of Art and Their Authors

Balthus with his model and niece / mit Model und Nichte Frederique Tison, 1956

1. A deceptive antagonism

In debates erupting over how to engage with works by artists who act in ethically problematic ways, two extreme positions are invariably taken. [1] One side assumes – in most instances, tacitly – that works are completely separable from their authors, and tends to believe that, however politically questionable it may be, what an artist (usually a man) says or does is utterly irrelevant to the discussion and assessment of their work. The fact that an artist such as Caravaggio, an oft-cited example, was convicted of manslaughter, or that Georg Baselitz has a big mouth and a penchant for misogynistic barbs, makes no difference to those admirers of their pictures who see a perfect disjunction between the work and the person of the artist.

The other side, meanwhile, more or less explicitly supposes that the work and the artist’s persona coincide. On the basis of this conviction, many works – such as Balthus’s painting Thérèse Dreaming (1938) – could be blacklisted. In 2017, thousands signed an online petition demanding that the Metropolitan Museum in New York remove this painting – which shows a seated girl in a reverie, one leg propped up so that her white underwear are visible – or to at least provide a wall text to contextualize it. [2] The petitioners argued that the picture romanticized the sexualization of children. Their point was lent additional plausibility by the fact that, a few years earlier, New York’s Gagosian Gallery had presented Polaroids taken between 1990 and 2000 for which Balthus had arranged one of his underage muses, Anna Wahli, in soft-porn poses in boudoir scenes. [3] This body of work, it seemed, left virtually no doubt about the artist’s pedophile leanings. In the eyes of all those who advocated the removal of Thérèse Dreaming, the painting not only promoted the sexualization of children, it also transmitted its author’s dirty-old-man fantasies. It is a view that is not unreasonable yet ultimately too simplistic – I will come back to this later. For now, I should note that Thérèse Dreaming was felt to be unacceptable not just because of its problematic motif but also because of presumed inseverable bonds between the picture and its author. The existing photographs that show Balthus in the intimate company of his muses would seem to confirm that he treated young girls in ways we would now describe as abusive. Thus, the public staging of his person influences the perception of his work (and vice versa); the product is read accordingly. However much Caravaggio aficionados and Baselitz enthusiasts may wish to consider an artist’s person and product as completely separate, it is quite difficult in such cases to actually do so. Of course, there is always the possibility that the artist’s defenders simply have no problem with a killing that is long past the statute of limitations, or with the kind of sexist provocations and improprieties that are still all too common in the art world.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, „Sacrificio di Isacco“, 1603

2. Advantages and disadvantages of an “art history without artists” – potentials and limitations of the biographical mode

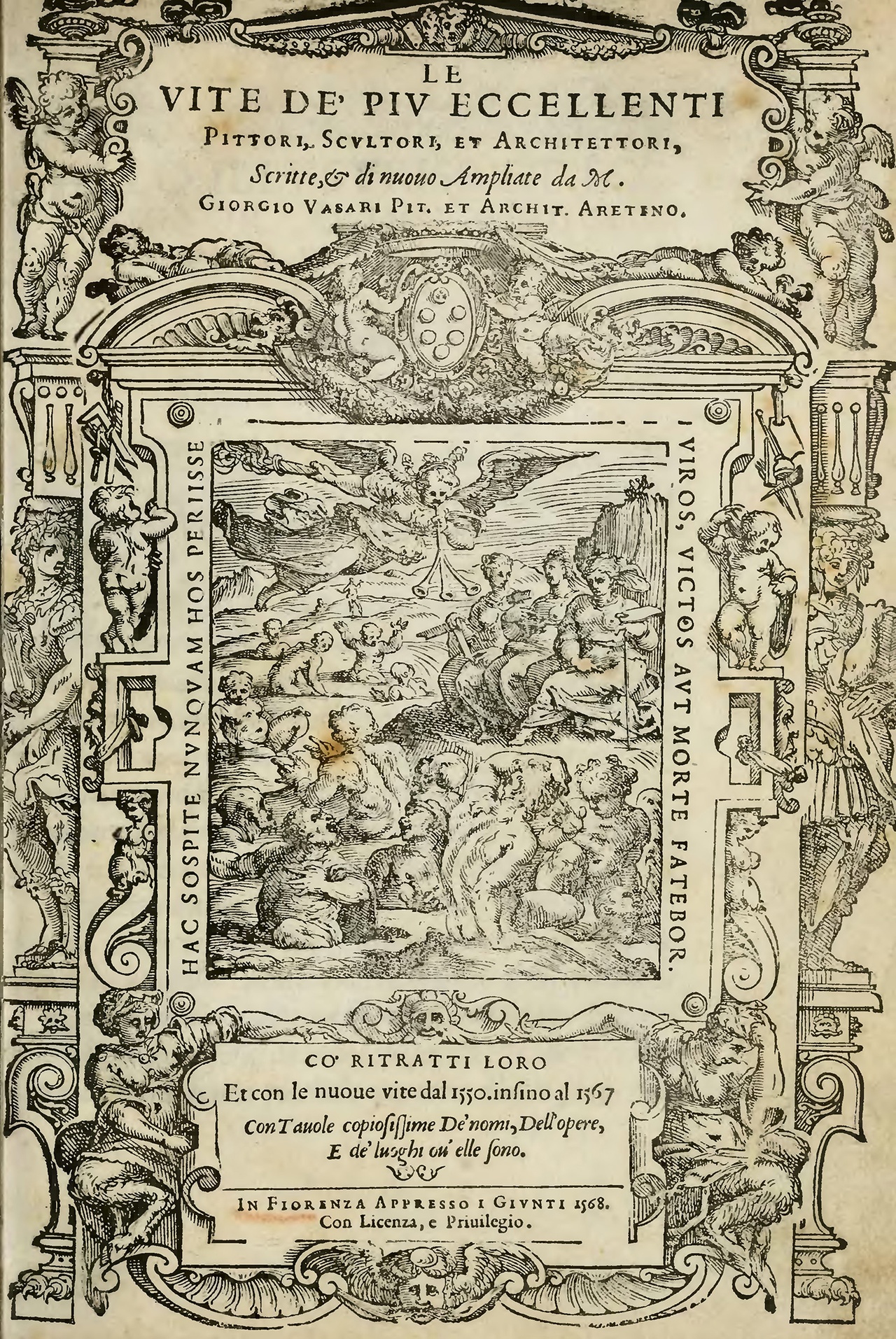

In the perspective of art theoretical scholarship, this antagonism – “separation” versus “identification” of product and person – reflects the contrast between two diametrically opposed approaches and methods. Those who believe that work and artist can be neatly disentangled stand in the tradition of a formalist “art history without artists” (to quote Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz’s critical formula), in which the artist’s empirical person makes no difference to the study of their work. [4] The assumption is that art’s formal language unfolds only in the act of contemplation, and so its authors – and their actions and life stories – merit no attention. In this perspective of a formalist art history, information on their personal affairs contributes absolutely nothing to an understanding of their work. In sharp contrast to this approach is the biographical method, whose stage, Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz write, artists first appeared on in the Renaissance. [5] Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550) may indeed be regarded as the primal scene of this mode of legend-spinning and biographically fixated art history: Vasari’s focus is on the habitus and demeanor of the artists he portrays – needless to say, all of them men. And the more favorable his portrayal of their character and actions, the greater his inclination to express approval of their works as well. How artists comported themselves and putatively lived was the dispositive criterion for Vasari’s value judgment.

Both this biographicist fixation on imagined circumstances of life, in the Vasarian vein, and the choice to flatly ignore the biographical factor in formalist art history, as in Clement Greenberg or Michael Fried, hold epistemological potential. Still, by adopting only one of these two perspectives, one aspect is consequently lost from view. To write “art history without artists” is to assume – quite rightly – that works of art are not mere reflections of their authors’ persons, and can accordingly not be reduced to, or explained with, those authors’ intentions. On the contrary, what an artist intends is often not what beholders end up seeing. Every work has unintentional facets. An early reference to this complex interrelation between the intended yet unexpressed and the unintentionally expressed may be found in Marcel Duchamp’s idea of the “art coefficient.” [6] According to Duchamp, any attempt to derive the true meaning of a work from the stated intentions of its author will end in fallacy: as I mentioned, what was originally intended is not necessarily found in the finished work, and what is more, one must not take artists’ statements – which, at least since the days of conceptual art and the shift it drove toward a conception of art as discursive, have arguably been an integral part of their creative output – at face value. They serve to generate meaning, that is true, but, like all other factors that produce meaning, they require decoding and interpretation.

Then again, the attempt to avoid biographicist inferences – a key concern motivating the proponents of “art history without artists” – comes with considerable risks, too. For example, it may lead us to overlook the references to the artist’s lifeworld that have been featured more and more richly in visual art since the historical avant-gardes. If one adopts a perspective that is averse to biography, the concrete biographical material recedes into the background, although it faintly yet unmistakably appears in the cubist collages of, say, Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque. Proponents of an unadulterated formalist approach would object at this point, arguing that what one encounters in works of art is never authentic life but, more likely, highly staged and mediated suggestions of life. And of course they would be right. Still, the problem remains that the methodology of neither formalist art history nor the biographical mode is capable of adequately analyzing the complex interrelationships between art and life or between product and person. [7]

Giorgio Vasari, „Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori“, 1550, frontispiece / Frontispiz

3. The market abstracts from the realities in which artists live and work while also molding those realities into legends that generate value

The peculiar interrelation between “product” and “person,” I believe, can be thrown into sharper relief by considering the process of value formation in the sphere of the market. At first blush, one might think that the original contexts in which an artist’s life and labors were set, as reflected in biographical narratives, are dissociated and repressed once the artist’s works circulate in the market. In the auction sphere, for instance, works of art are traded as commodities of a special kind, typically without regard to the conditions under which they were made and the frameworks in which they have been embedded. What matters instead are what Jens Beckert has called the “fictional expectations” of the various parties involved in the trade, which is to say, the hopes of future increases in market value these parties invest in the works. [8] What preoccupied the artists once upon a time or still preoccupies them now, the personal or artistic concerns that they believe were or are at stake in their works, are largely irrelevant in the market and the auction sphere. This disregard for the contexts of life and work notwithstanding, the processes of value formation in the auction sphere also establish a linkage between person and product of the sort that is characteristic of the artist’s biography genre. Just consider the legends about artists that flank the works for sale in the auctioneers’ catalogues. The works even become personified through rhetorical devices that are customary during auctions – an auctioneer may talk about “a Warhol” or “a Richter” as though they were people. It is not a coincidence, I would argue, that legends and anecdotes are so popular in the auction sphere: beginning with Vasari’s Vite, a life story often upstages the detailed description of a work. And even today, the legends around an artist help endow their output with credibility. What is more, these stories are a tried-and-true tool to promote sales. An artist’s reputation for being particularly eccentric or extreme, for example, usually has a positive effect on the market value of their art. Then again, many artists work to ensure that their purported personalities resonate in their works. From Raphael to Gustave Courbet, from Andy Warhol to Joseph Beuys, from Anne Imhof to Tschabalala Self, many artists past and present have been experts at staging themselves in ways that make for good stories. An artist’s honing their public image has long been seen as an essential part of the profession. [9] Needless to say, this is especially true in the age of social media. How artists perform for their audiences on social media profoundly informs what those audiences make of their work.

In light of these observations, the relationship between product and person in today’s art economy (which is partly set in the digital sphere) must be characterized as one of metonymic interrelation. One side (the person) “signifies” the other (the product), and the product conversely rubs off on the person. Although the work is not reducible to – does not coincide with – the person of its author, the lived realities reflected in artworks will affect the image we form of the artist as a person. Conversely, the artist’s public image is bound to have a massive impact on our perceptions of their practices.

Georg Baselitz, „Die große Nacht im Eimer“, 1962/63

4. It’s complicated

But the question is: How does the metonymic interrelation I have sketched between product and person shape our engagement with works by artists such as Georg Baselitz or Balthus, who say or do things that are politically and/or ethically questionable or worthy of outright condemnation? Let us start with Baselitz, who, in an interview with Der Spiegel in 2013, had the impertinence to argue that women cannot paint. [10] He tried to buttress this hopelessly misogynistic claim by pointing to the allegedly lower market values of women artists’ works: the market, he said, does not lie. Ignore for a moment the fact that Baselitz – like, it should be noted, many market players – confused market value with artistic relevance and brushed aside the rapidly growing number of women who have done well in the market: because of the blatant sexism of his statements, I, as a female-identifying individual, now have a hard time looking at his pictures without feeling indignation. Yet instead of rejecting his entire oeuvre, we might try a more productive tack, in light of the metonymic interrelation between product and person, and consider his paintings under the aspect of male heroism and misogyny. His Hero Paintings series, for instance, created in 1965–66, might be read as the desperate (and literal) rearing-up of a masculinity that realized that its privileges were in jeopardy as the patriarchy had begun to crumble. The soldierly men—whether larger-than-life “friends” or disabled war veterans—in these pictures gesture toward a male dominance that went into crisis after 1945 and literally needed to be re-erected. When artists like Baselitz revisited the trope of the soldier in the 1960s and “stood to attention” in their own public appearances, they, on the one hand, grappled with the repressed legacy of the Nazi era. On the other hand, they sought to defend terrain that had already been lost. What is more, in the Hero Pictures it feels like Baselitz was intent on excluding women from his pictorial politics and vision of heroism conceived as exclusively male also because, in the real world of the 1960s, they were increasingly vocal in their demands for participation. A little earlier, in Die große Nacht im Eimer (The Big Night Down the Drain, 1962–63), which caused a scandal, he had already mounted a wooden-looking erect penis in an effort to ward off the waning of phallic power: a man who, it seems, felt threatened and castrated by women tried one last time to seize the initiative. His visual insistence on a purely male heroism echoes decades later in the attempt—in this perspective, the rather desperate attempt—to discredit women painters. Both in some of his pictures and in that remark, Baselitz would seem to fend off the threat women represent by excluding and/or disparaging them while clinging to an exaggeratedly masculine and grotesquely bellicose heroism (witness lines such as “my pictures are battles”).

Balthus’s Thérèse Dreaming presents a similar case – this picture, too, may be read as the manifestation of a male fantasy, in this instance with pedophilic overtones. The girl sitting with her legs spread just wide enough to reveal her underwear keeps her eyes closed and seems to be absorbed in some sensual reverie. She encourages voyeuristic desire while also defying it: her sexual pleasure remains beyond the beholder’s reach. Balthus has placed the motif of a cat lapping up milk at the seated girl’s feet as a symbol of young girls’ sexual awakening. The word “dreaming” in the title, moreover, is an obvious nod to Sigmund Freud’s interpretation of dreams and his theory of sexuality – Freud, it is well known, was a leading pioneer of a new understanding of infantile and adolescent sexuality that was influential in Surrealist circles and also recognizably underlies Balthus’s composition. [11] Since then, though, the Freudian premise has been used as cover for many abuses: note the debate over pedophilia within Germany’s Green Party. Around 1935, by contrast, sexual transgression was still seen as artistically “progressive.” Therefore, Balthus’s pictures also need to be located in the context of the contemporary thought of, say, his brother Pierre Klossowski, or of Georges Bataille, in whose erotic novella Story of the Eye milk plays a central role as a symbol of the erotic and amorphous. [12] I did not realize until much later, in the 1990s, that women often paid the price for the transgressive fantasies of these men, as is exemplarily illustrated by André Breton’s Nadja. [13]

Yet unlike Baselitz, whose misogyny and gynophobia occasionally leave traces in his paintings, Balthus accords the figure in Thérèse Dreaming a certain degree of agency and elusiveness. While she is exposed to the gazes and desires of her voyeuristic beholders in a way that certainly kindles fantasies of abuse, her closed eyes and sensual mien suggest a sexual pleasure that is withheld from and closed to the beholders. The cat lapping up milk might be a proxy for female ejaculation and an enjoyment that Thérèse Dreaming only hints at. The figure’s sexuality is on display and proffered for our contemplation, yet she also appears self-determined and unattainable. It is possible that this very unattainability of the girl makes her an especially arousing sight to the pedophile. Still, what matters is that the author’s product – though it, too, is steeped in his personal proclivities – takes on an idiosyncratic meaning that ultimately cannot but affect our view of the artist’s person as well. For in the end, it is he who is responsible for the elusiveness of the figure in Thérèse Dreaming. Just as what an artist says (such as Baselitz’s sexist statement) and does (such as Balthus’s staging himself as an aristocratic dandy with a weakness for young girls) makes their output appear in a different light, works are ideally more complex than their authors. The latter’s lifeworld, predilections, and convictions resonate in their art, but the works have the strength to break away from or transcend their authors as well. It is worth noting, however, that such intractability of the picture will, in the final analysis, be credited to the author by virtue of the simple fact that they made it. That is to say, the bond between product and person must be imagined as distinctly nonbreakable, and yet at the same time the two never coincide.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of Texte zur Kunst and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and Vom Nutzen der Freundschaft (Spector Books, 2022).

Image credit: 1. © shutterstock, The LIFE Picture Collection, photo Loomis Dean; 2. Piasecka-Johnson Collection, public domain; 3. Uffizi, public domain; 4. © Georg Baselitz 2022, photo Jochen Littkemann

Notes

| [1] | See “Wo liegen die Grenzen der Kunstfreiheit?,” 13 Fragen, ZDFkultur. And consider the éclat sparked by the Documenta 15 artist Hamja Ahsan’s verbal assault on the German chancellor, in which the relationship between product and person once again played a key role: Ahsan called Olaf Scholz a “neoliberal fascist pig” on Facebook, prompting indignant reactions from the right-wing press, led, not surprisingly, by the Axel Springer publishing group’s Bild tabloid. The exposition’s artistic directors felt the need to inform the public that what an artist said outside the show was none of their concern, as though person and product were neatly separable. Ahsan’s statements, by this logic, in no way affected the art he exhibited. The Springer press empire’s writers, by contrast, seemed wedded to the belief that the artist, his statements, his works, and the context in which they were displayed were one and the same, and they demanded an immediate end to taxpayer-funded support for Documenta. The right-wing populist nature of their intervention aside, these critics conveniently ignored the fact that insulting politicians is a well-established avant-gardist trope. |

| [2] | Mia Merrill, “Metropolitan Museum of Art: Remove Balthus’ Suggestive Painting of a Pubescent Girl, Thérèse Dreaming, Care2 Petitions website, accessed October 24, 2022. |

| [3] | As the petition succinctly concluded, “The artist of this painting had a noted infatuation with pubescent girls” (ibid.). |

| [4] | Ernst Kris and Otto Kurz, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist: A Historical Experiment, preface by E. H. Gombrich (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), 7. |

| [5] | Ibid., 32–33. |

| [6] | See Marcel Duchamp, “The Creative Act,” in Salt Seller: The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), 138–40, quote 139. |

| [7] | On the relationship between the artist’s product and person, see also Isabelle Graw, “How Much of a Product Is a Person?,” in High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture, trans. Nicholas Grindell (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2009), 163–65. |

| [8] | See Jens Beckert, Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). |

| [9] | See Beatrice von Bismarck, Auftritt als Künstler: Funktionen eines Mythos (Cologne: Walther König, 2010). |

| [10] | Georg Baselitz, “Meine Bilder sind Schlachten,” interview by Susanne Beyer and Ulrike Knöfel, Der Spiegel, January 20, 2013. |

| [11] | See Beate Söntgen, “Immer wieder Thérèse: Balthus’ Mädchenbilder,” in Balthus, exh. cat., ed. Raphaël Bouvier (Basel: Fondation Beyeler; Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), 131–41. |

| [12] | Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (New York: Urizen, 1977). |

| [13] | See Isabelle Graw, “Unentschieden: Klossowskis Frauenbilder,” in Silberblick: Texte zu Kunst und Politik (Berlin: ID Verlag, 1999), 145–58. On Breton’s Nadja and the sacrificial woman, see also Isabelle Graw, “That Belongs to Me! Reflections on Property and Value in Artistic Production,” Texte zur Kunst, no. 117 (March 2020). |