DECOLONIZING THE CANON?

Victor Meirelles, „Primeira Missa no Brasil“ (First Mass in Brazil / Erste Messe in Brasilien), 1859–61

I am an art historian specializing in Brazilian art and design, circa 1800 to 1950, a subject area that remains marginal after more than two decades of academic output in world art studies and global art history. From my obscure corner of the field, the canon is just as formidable and unassailable as it ever was. Trying to convince a museum director in Europe or the United States to exhibit the kind of art I study is bound to elicit a bemused smile. Books on the subject are hard to come by in English, French, or German. I was lucky to have one published last year – by Cambridge University Press, no less – but, significantly, it came out not as a volume of art history but in their Afro-Latin America series. [1]

The art made in Latin America is rarely taken seriously as art, much less studied as part of a shared art history. It is not just the culture of the Other, in the way that Africa and Asia are other to the European mind, but the expression of a liminal identity, deceptively familiar yet clouded by a disturbing in-betweenness. Mainstream art history has traditionally made little room for Latin American art. [2] The works themselves most often remain unseen and, when viewed, tend to be interpreted reflexively as offshoots or accessories of North Atlantic counterparts. Or else, they are written off as nativism. One major exception to that historiographical rule is the period since the Cold War. Latin America’s contribution to Concrete Art and Neo-Concretism, as well as conceptual, installation, and performance art, is widely recognized. Another exception, to a lesser degree, is Mexican muralism, usually deemed important by art historians, though often underestimated in terms of its originality and impact.

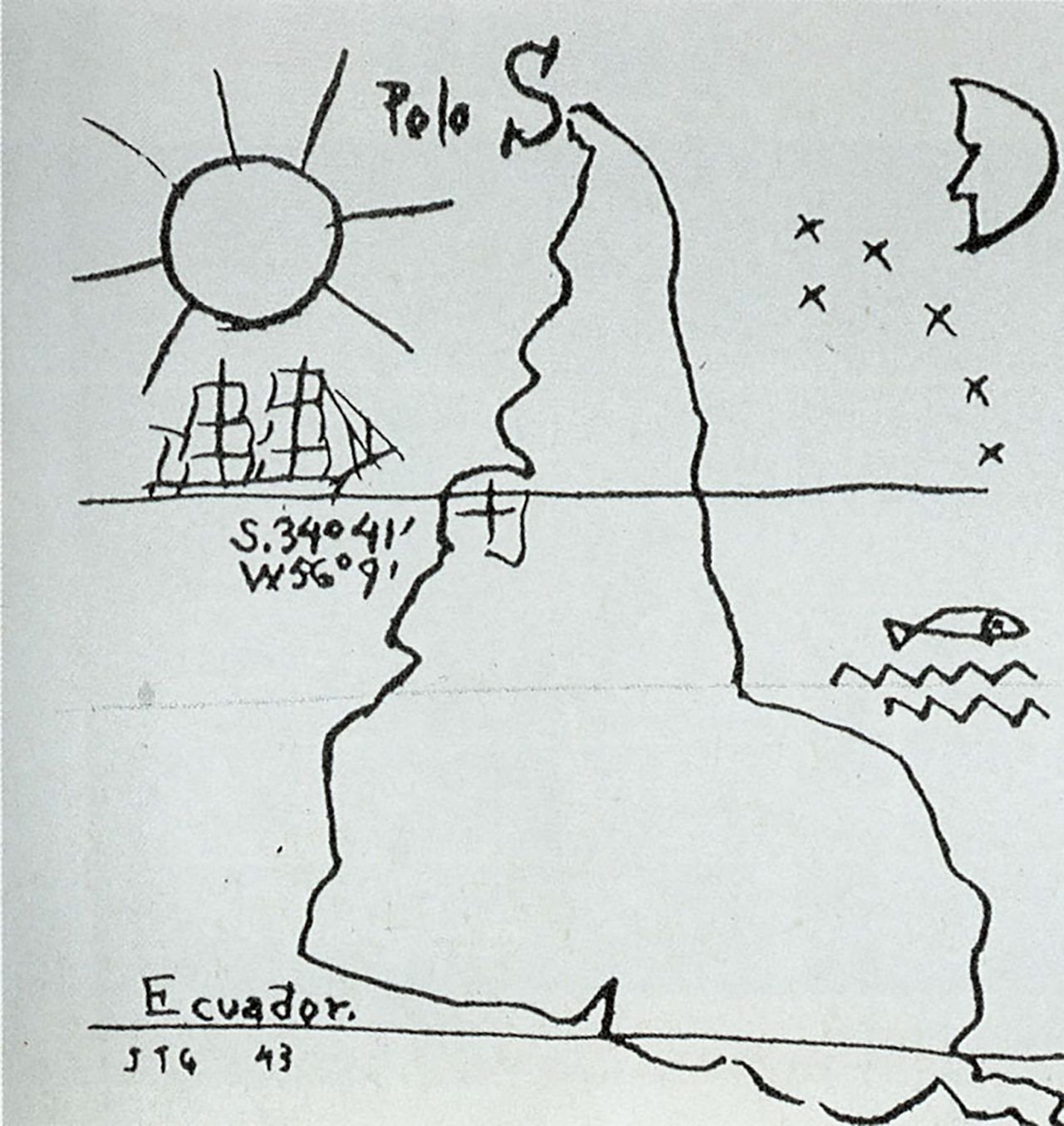

Joaquín Torres-García, „América Invertida“ (Inverted America / Umgedrehtes Amerika), 1943

The assimilation of contemporary Latin American art into the global canon is worth thinking about. A notable aspect of its rise to prominence is how that inclusion took place – as a decidedly transnational effort, filtered through institutions located outside Latin America. It began about 30 years ago, among forward-thinking curators (Guy Brett, Catherine David, Jean-Hubert Martin, and others), and gained momentum via collectors and the art market, achieving something like canonicity only very recently. International recognition, in turn, paved the way for a renewal of scholarship. That is a convincing example of how the canon can be expanded. The question remains whether it also constitutes an exercise in decolonization. Is it decolonial when a revision of the canon upholds the authority of those who keep and guard it?

Decolonizing the canon is easier said than done. One reason is that we must submit to open-ended discussions over what the canon is or whether it even exists. Those who conduct such debates are usually situated within the places where the canon is formed and, therefore, to which it least applies. They tell us the canon is a shifting historical construct, that what is included depends on conflicting views and disputes over authority. Those observations are true. Their truth does not change the situation for those who stand outside the gates. To us, such considerations are like reading a table of nutrition facts to a hungry child. We may recognize the values as correct, but they do not feed us. Viewed from the exterior, the shape of the art historical canon is glaringly obvious. We have always known its gatekeepers, and we instinctively dread that, no matter how much it shifts, it will still exclude us.

Decolonizing the canon is also difficult because we must now vie for the term decolonization. A decade ago, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang cautioned that decolonization is not a metaphor. [3] It is, they argued, about settler colonialism and the historical displacement of peoples from their land and cultures. It is also about breaking down the social structures and mental strictures deriving from colonization and its aftermath. Decolonization means listening to the colonized and, if you are not one of them, bolstering their claims. It is not a synonym for other worthy causes – not even anti-racism, with which it is so closely bound up. Its discussion should focus primarily on the victims of colonialism, past and present, not on the domestic politics of colonial powers.

Raquel Forner, „Mujeres del mundo“ (Women of the world / Frauen der Welt), 1938

Decolonization is not a metaphor, but that is exactly what it has become in many elite cultural institutions. It is right and praiseworthy when museums, biennials, and universities seek to redress the balance of power within; however, in this instance, acting locally is not necessarily akin to thinking globally. The core issues of decolonization revolve around the unevenness of power between regions of the globe, as well as the systems of oppression this imbalance engenders, often based on ethnic and cultural difference. In a word, imperialism – a term uncomfortably missing from some current debates on decolonization. [4] Paul Gilroy said in a recent interview that he is not particularly interested in decolonizing the 1 percent. [5] That is a provocation, of course, but it points to the larger geopolitical dimension. In the metaphorical struggle to decolonize the richest places on earth, what used to be known as the Third World often ends up at the back of the queue.

The inclusion of contemporary art from Latin America begs the question of why earlier periods have been denied the same treatment. The unspoken assumption is often that the older art was bad or uninteresting. Can many centuries’ worth of cultural production, spanning numerous peoples and a vast expanse of the globe, really be so unworthy of exploration? Or is it, rather, a question of the criteria by which we define art and its place in history? Works produced in Latin America before the late 20th century tend to bring up uncomfortable issues of emulation and appropriation, which Partha Mitter thoughtfully terms “the pathology of influence” in the history of art. [6] Cultural borrowing is understood as a purposeful and informed activity when the dominant culture takes from the dependent one. When it happens the other way around, it is seen as sterile and uninteresting.

The centrality of concepts such as movement, style, and period to art historical discourses traps us in circular debates about belatedness, derivation, and asynchronism. We rarely succeed in superseding what Mitter elsewhere labels the “Picasso manqué syndrome.” [7] The situation is even worse for what came before Modernism. We have hardly begun to scratch the surface, on either side of the Atlantic, of the complex linkages between notions of academicism and the dynamics of empire. For the European imagination, Latin American art before the 1920s is an incongruous hybrid: too recognizable to inspire awe, too baffling to rate comparison. It is routinely shunned, by a chastened Europe, for its success in endowing colonial brutality with a veneer of civilization, only to fall into the gaping void of its own contradictions.

Eliseu Visconti, „Roupa estendida“ (Hanging clothes / Aufgehängte Kleidung), 1943

What needs to change are the terms of debate. Latin American art must be understood as a creative response to colonialism and imperialism, not as a failed attempt to emulate the colonizer. Artists in the Americas have always faced the challenge of negotiating cultural difference against a backdrop of brutal extractivism, enslavement, racism, inequality. Many have risen to the task with vigor, wit, even brilliance. To judge their work according to outmoded formalist paradigms is to miss the point of what they achieved. Transposition is never neutral. Scholars must take the context in which the works were produced as the foundation for interpreting their meaning, much as any historian would in dealing with European art. We need to embrace what sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos calls “the epistemologies of the South.” [8]

To arrive at a proper historical understanding of Latin American art and its worldwide significance requires a greater emphasis on cultural transfer and transculturation, as well as a good deal less ethnocentrism on the North Atlantic side. Those who invented the discipline of art history, centuries ago, are no longer entitled to define it exclusively. We want equal opportunity, more than lessons on methodology. Among the enemies of a truly global art history is a resurgent identitarianism that continues to partition human experience into flawed categories of “us” and “them.” Despite recent efforts, the field is still circumscribed by linguistic, institutional, and jurisdictional boundaries enforced by nation-states, not least in terms of funding and academic positions. The nationalism of epistemology is hard to shake.

Decolonizing the canon means taking seriously the discontents of those excluded from the art historical mainstream. That does not mean tokenism – the co-opting of selected individuals to buffer institutions from criticism. It means opening spaces in which to discuss critically the long history of domination by a Eurocentric conception of art. Canons exist to affirm the genealogy of power. Those of us who come from countries subjected to regime change, as well as to fiscal policies that eviscerate spending on education and research, gaze upon the present debates on decolonization with intuitive sympathy but also with a lurking suspicion. After five centuries of North Atlantic imperialism, we are now being told by our former colonizers how to decolonize ourselves. If you see nothing wrong with that equation, then the mindset of colonialism has not substantially changed.

Raphael Cardoso is an art historian and writer who has authored many books on 19th- and 20th-century Brazilian art and design, the latest of which is Modernity in Black and White: Art and Image, Race and Identity in Brazil, 1890–1945 (Cambridge University Press, 2021). He is a member of the postgraduate faculty in art history at Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro and a research associate at the Institute for Latin American Studies of Freie Universität Berlin.

Image credit: 1. Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, public domain; 2. Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales, public domain; 3. Courtesy of Fundación Forner-Bigatti; 4. Public domain

Notes

| [1] | Rafael Cardoso, Modernity in Black and White: Art and Image, Race and Identity in Brazil, 1890–1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021). |

| [2] | The term “Latin America” came into being in the 1830s, following the independence of most of the present nations of South and Central America. It was promoted by French foreign policy, in a bid to expand influence in the region, and embraced by Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking intellectuals anxious to distance themselves from Anglo-American dominance. “Latin American art” is here used to refer to works produced after this period. |

| [3] | Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. |

| [4] | By imperialism, I refer to systems of domination exercised through a mix of cultural ascendancy, political influence, economic supremacy, and military might. These may persist long after colonial rule ends. In the Latin American experience, the independence movements of the early 19th century did not substantially alter the fact of imperialism, which continued to be exercised by powers distinct from the original colonizers. |

| [5] | Yohann Koshy, “The Last Humanist: How Paul Gilroy Became the Most Vital Guide to Our Age of Crisis,” Guardian, August 5, 2021. |

| [6] | Partha Mitter, “Decentering Modernism: Art History and Avant-Garde Art from the Periphery,” Art Bulletin 90, no. 4 (December 2008): 531–48. |

| [7] | Partha Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1922–1947 (London: Reaktion, 2007), 7. |

| [8] | Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide (London: Routledge, 2014). |