“STILL ILL?”

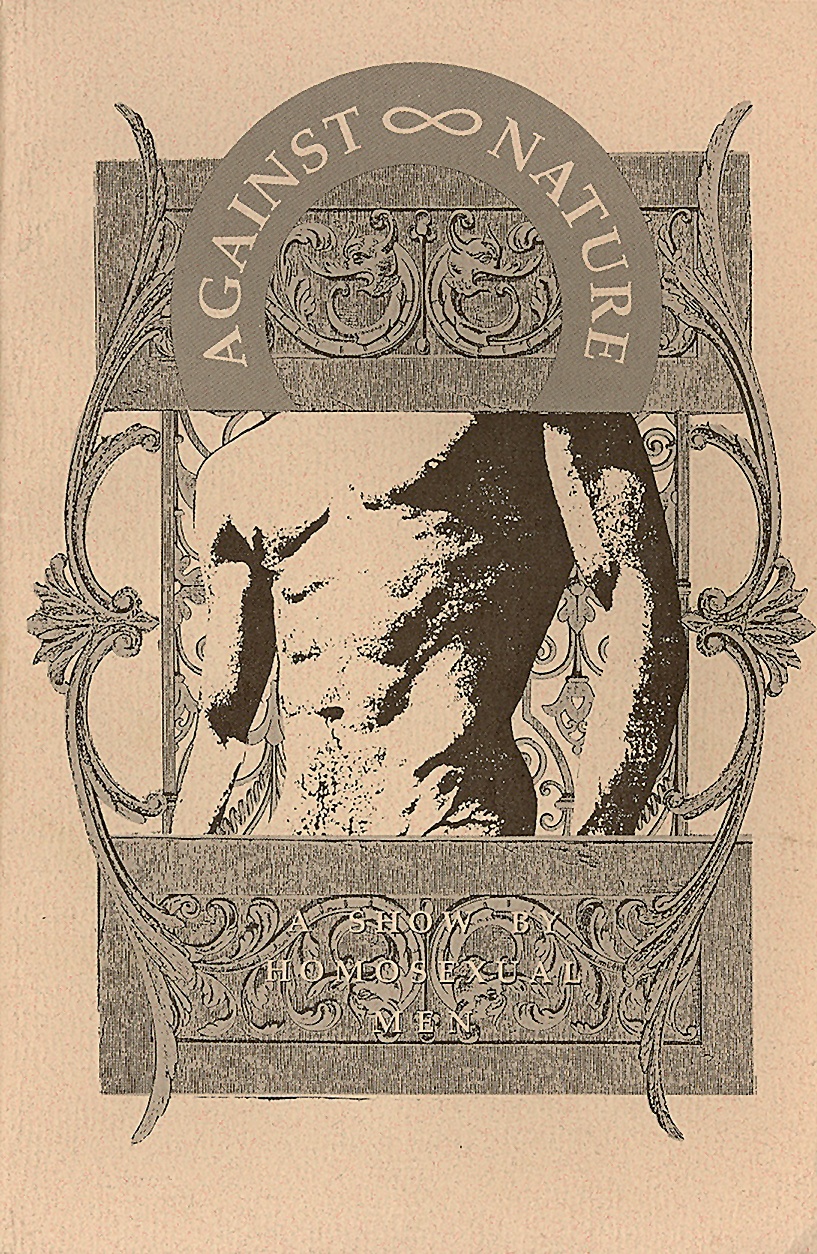

„Against Nature“ (Arnold Fern), Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 1989, installation view / Ausstellungsansicht

To quote a controversial homosexual, “stop me if you think that you’ve heard this one before.” AIDS is back. I don’t mean to sound melodramatic – it never left us. Yet, it doesn’t take a trained eye to notice a shift has taken place over the course of the past decade, particularly regarding the position AIDS crisis culture occupies within debates surrounding the value of “politically engaged” art. A bit of necessary housekeeping: I use the term AIDS crisis culture, or simply crisis culture, [1] to refer to the visible height of the epidemic in the US (roughly 1987–1996; “visible” due to the collected energies of countless activists, artists, and cultural theorists). AIDS is not over, and no simple linear periodization could ever fully address its temporal complexity. In the past few years, practically every major US museum worth its salt has staged a large-scale retrospective for one or another crisis culture artist; the publishing industry appears to be locked into an unending race to unearth out-of-print texts from the era (is your art book press even good if it doesn’t have a David Wojnarowicz title on its list?); AIDS historiography is now an academic discipline of its own. If AIDS activism originally conceptualized its cultural battle as a matter of piercing the silence of mainstream institutions – a battle which was to be waged through excessive self-representation – the present strikes us as a purgatorial hangover: a still-throbbing militant aggression has found its platform at the expense of a clear target.

A certain anxiety about the value of representation has taken hold. To the extent that gay men were accorded some level of mainstream legibility during the height of the crisis, such representation almost unwaveringly took the form of desexed images of virally wasted and emaciated bodies, a smarmy nod to the idea that such men could only elicit the compassion of a general audience once they had lost all hope of acting upon their sexual impulses. In light of such dreary conditions, many AIDS activists took up a reactive theory of homoerotic representation, in which the naked depiction of gay men as sexual beings was taken to inherently constitute a form of radical political action. [2] Within the context of crisis culture, it is easy to understand how the literal representation of homoeroticism might appear to carry a certain anti-institutional charge: if institutions refuse to acknowledge the mere existence of your subjectivity, self-representation offers a ready-at-hand tool for reversing their deadly grip on collective consciousness.

Today, cultural institutions, by and large, seem to have little problem acknowledging AIDS. If anything, we are bearing witness to an unusually fervent hunger for (read: financial interest in) cultural programming that honors the political history of AIDS activism – programming that is so often justified through a vague, boilerplate set of talking points about “queer ancestry,” “remembrance,” “resistance,” “mourning.” One encounters a paradox: we are taught to understand the reproduction of crisis culture in our present as something which is politically valuable precisely because it speaks truth to a gritty form of historical realism, one that righteously offends the activist-pacifying palate of liberal morality. Yet, it is so often the very institutions associated with such ideals of liberal morality, bourgeois refinement, and post-Enlightenment humanism that advance these precise arguments regarding AIDS and its representation.

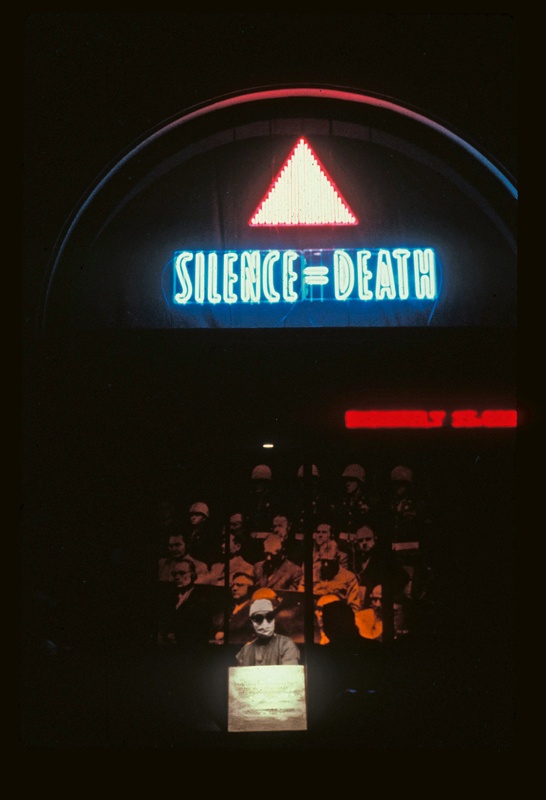

Gran Fury, „Let The Record Show“, 1987

This piece is an attempt to parse apart a relatively underexamined shift in popular framings of the relationship between artistic representations of desire – particularly, “homosexual” desire – and political action: a shift, I want to suggest, that AIDS activism and its attendant cultural theorists have become unwitting accomplices in. Our understanding of the social function of representing desire has been whittled to a fine point: literalism has become, perhaps ironically, a metaphor for assessing the fundamental value of a work of art, particularly as it is imagined to exist along a zero-sum spectrum of politically retrograde (false) to politically radical (accurate) expressions. The ideal of an unending revolution – a perpetual crisis constantly deferring the luxury of more passive, decadent, or analytical considerations of desire – subsumes representation, jettisoning any consideration of what sexually charged material might be capable of doing socially beyond a narrow conception of political consciousness raising. Such potentially enthralling concepts as artifice, irony, abjection, and trickery are paved over in the interest of constructing a direct through line between, on the one hand, a literal reading of the content being represented and, on the other, some universal political truism assumed to be hiding just beneath the surface.

The bulk of critical writing done on AIDS history in recent years has essentially fallen in line with such literal thinking. Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show, for instance, makes a relatively simple argument about the politics of representation surrounding AIDS: in order to apprehend the significance of a social movement, one must defer to the lived experience of those who participated in the movement itself. “AIDS has been grossly misrepresented and mis-historicized,” [3] Schulman puts it bluntly. Written in response to what Schulman takes to be the prevailing feel-good metaphors of mainstream AIDS historiography – the fetishistic myth of the heroic gay male individual; the benevolence of heterosexuals; the existence of a unified approach to AIDS activism – Let the Record Show offers a historical corrective in the form of unmediated, raw recollections from those who served time on the front. It arranges decades worth of archival research, interviews with former ACT UPers, and personal recollections into a dense sprawl, attesting to a kaleidoscopic image of the lifestyles of New York AIDS activists. The concept of accurate representation as a proxy battle over a contested field of truths is accorded de facto primacy. My aim is not to critique the political efficacy of such thinking. In order to win, militants need such rhetorical tools at their disposal: the negative image of a clear enemy; the determination to act with speed and sobriety; the conviction that their experience amounts to something more than individual suffering. My concern, rather, is for the point at which historically and culturally specific political tactics become a decontextualized barometer for analyzing culture writ large.

What does one hope to gain by insisting on accurate representation? A defensive position comes to mind: distorted narratives regarding AIDS directly contributed to the unchecked spread and death toll of the virus – by contrast, accurate representation stands to save lives. Fair enough. There is a second, more active claim at play, however. By arguing that representation is only valuable insofar as it accurately depicts the political realities of one’s lived experience, one tacitly upholds the idea that subjectivity is coterminal with the political histories and ideologies that give it legible shape. This is a radically positive image of existence: there are no fundamental negations or exclusions underlying subjective experience beyond the pale of political representation, only socially produced degrees of illumination and obfuscation which allow certain articulations of existence to shine whilst others languish in the shadows. This image of subjectivity is rooted in faith: it doubles down on the conviction that there is a possible world in which all aspects of one’s lived experience would be made to flourish without political impediment, in which all subjectivities would become whole, harmonious. Such a view holds onto the strange conviction that one’s particular subjectivity would not only continue to exist, but would in fact become a greater version of itself, in the absence of the political repressions that give it shape – while homosexuality, for instance, is only legible in terms of its deviation from heterosexual mores, the destruction of such mores would, paradoxically, improve rather than destroy the very conditions that allow homosexuality to articulate itself in the first place. This is a messianic vision: a theological metaphor of final deliverance, of a deferred future in which we finally become ourselves as we already exist. This form of thinking is foundational to projects like Schulman’s: social change, she writes, depends upon the unforced arrival of the proper “zeitgeist” [4] – a word which can conveniently mean anything, and thus nothing at all. The task of radical intellectualism in the interim period between zeitgeists, Schulman posits, is to archive reality as it has actually happened, to lay bare the political truth of our shared history. When the moment comes for this history to finally be made legible, the whole truth will spring forth naturally into the light of day, imposing a vicious articulation of our true selves upon the false totality of mainstream culture.

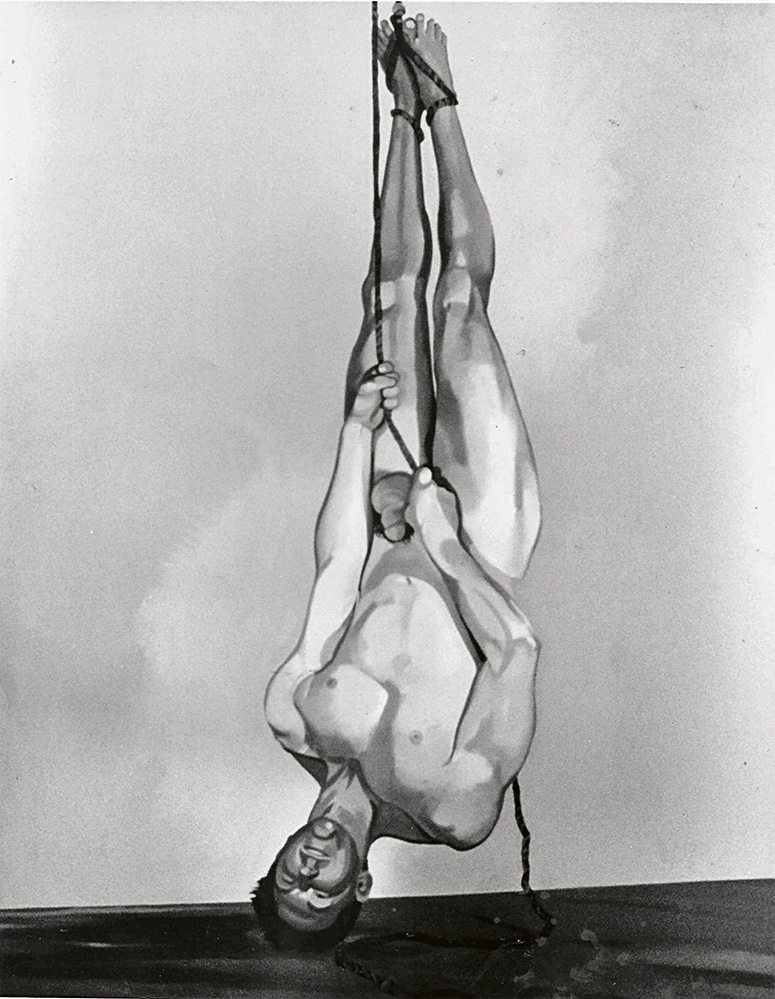

Kevin Wolff, „Hanged Man“, 1986

The roots of such thinking can be partially traced back to the very cultural theories espoused by certain prominent AIDS activists themselves. Humor a brief historical detour: in January of 1989, a show entitled “Against Nature: A Group Show of Work by Homosexual Men” opened at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE). Curated by a young Dennis Cooper and even younger Richard Hawkins, the show assembled new works by a loose cast of visual artists and writers, including Gary Indiana, Nayland Blake, Vaginal Davis, Kevin Killian, and Peter Christopherson from Coil/Throbbing Gristle/Psychic TV. While originally conceived by Joy Silverman, LACE’s director, as a coalitional display of solidarity with AIDS activism, the actual show itself was considerably more melancholic, eschewing any clear reference to AIDS activism and instead focusing on work which evinced an “irreverence for the cultural and moral standards imposed by and for heterosexuals, and a reverence and desire for, mixed with anxiety about the male body.” [5] As Cooper recollects, “In the context of ‘Against Nature,’ homosexuality was like an assignment, in a weird way. It was like, ‘ok, we’ve found this problem and we want to counter it.’ So, it was very much about being gay – we said ‘homosexual’ on purpose, of course.” [6]

The closest one gets to a direct analysis of the show’s themes is in Hawkins’s introductory essay, which is structured as a short analysis of J. K. Huysmans’s decadent novel Against Nature, from which the show derived its name:

The presentation of the grosser details of illness in a context other than their own instigates a sense of sublime release amongst those familiar with loss/illness […] not exactly instigating pleasure, but presenting what the abjection is not, while still referring to and containing the abject itself … flipping fear, through distancing, into irony. [7]

While direct mentions of AIDS are scant throughout the show’s materials, representations of homoeroticism abound: Boyd McDonald waxes poetic over Hollywood actors’ bulges, Kevin Wolff paints images of nude boys sniffing underwear and hanging from ropes attached to their ankles, Dennis Cooper weaves sparse tales of AIDS-stricken teens being gangbanged in bar bathrooms.

In an ironic deflation of Huysmans’s text, whose narrator strives to transcend the triviality of daily life by embracing the unfettered pleasure of a reclusive aesthete existence, many of the works gathered in “Against Nature” negotiate pleasure as something which is remarkably contradictory, neither purely individual nor distinctly collective, politically salient nor spiritually sublime, fully controllable nor beyond our grasp. In his contribution to the show’s catalog, Kevin Killian writes, “I was in New York having an awful kind of sex on the night of the Stonewall riots in 1969,” [8] placing homoeroticism outside of the context of political action while also denying it any sort of transcendent grandiosity; elsewhere, Tony Greene’s contribution to the catalogue’s back cover, which depicts a masked plague doctor with the words “silence equals death” overlayed in a stark white font, creates a mutually deflating dialectic, undercutting the dated mysticism of plague imagery through the inclusion of a contemporary political slogan, while simultaneously injecting the deadening ACT UP catchphrase with an air of conspiratorial esotericism.

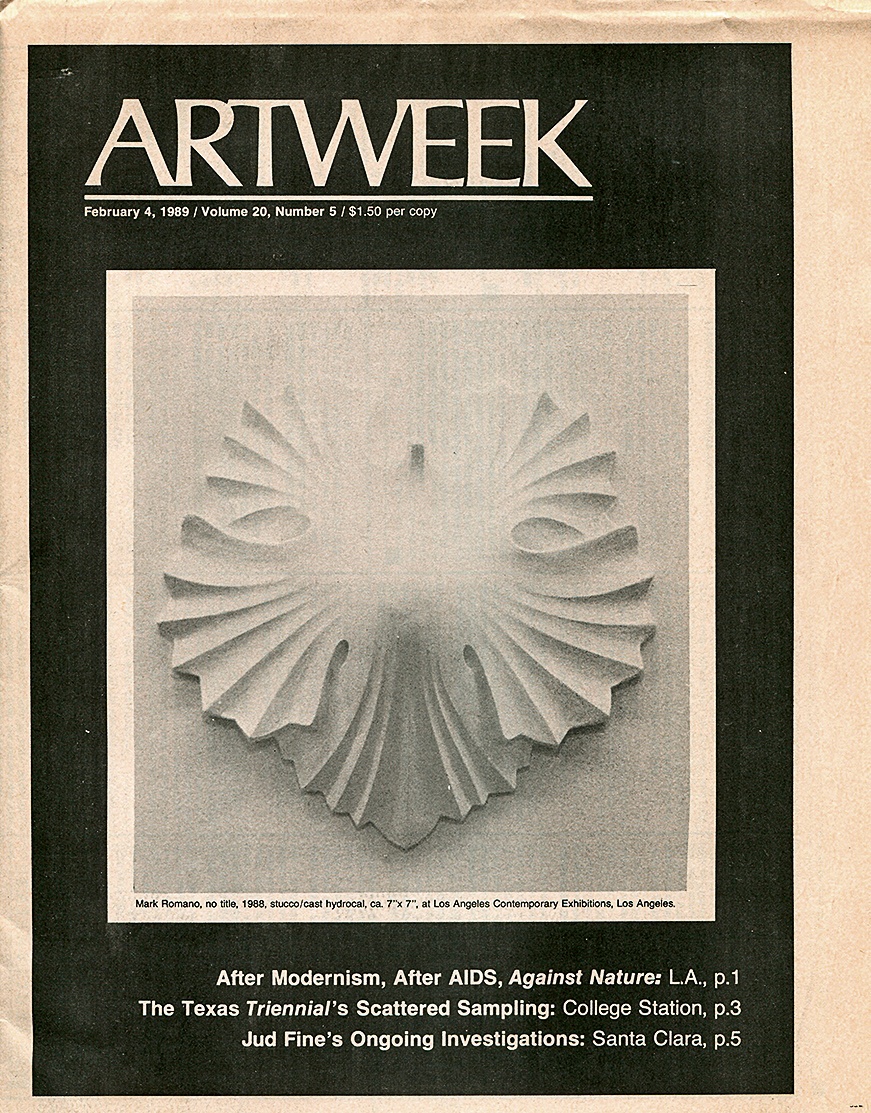

Title story on / Titelgeschichte zu „Against Nature“

Throughout the show, homoeroticism appears largely as a conduit for accessing larger themes of fear, paranoia, isolation, and, of course, horniness – but not homosexuality itself. There is no total unity of vision to be found, but rather a delirious, contradictory give-and-take between competing registers of reality. “AIDS,” as Cooper puts it in the show’s catalogue, “ruined death” [9] : the elimination of any clear stopgap between the desubjectifying jouissance of sexual pleasure, on the one hand, and the very real possibility of one’s own demise, on the other, has rendered it impossible to conceptualize pleasure with any sense of grandiosity or bravado.

In place of the militant theory of pleasure put forth by writers like Douglas Crimp, which positioned homoerotic representation as a tool for both materializing and putting into action one’s political subjectivity, the vision of homoeroticism laid bare in “Against Nature” is one of insurmountable confusion and ambivalence: pleasure offers neither the prospect of self-knowledge nor the possibility of political respite. Artifice, delirium, and disconnection abound: an anarchic suspicion that the world will never come match one’s individual fantasies takes hold. And yet, the continued expression of longing, desire, and attraction in the face of such impossibility places much of the work outside of the realm of pure aesthetic contemplation – if there is an absence of political bravado, there is likewise an absence of Huysmans-worthy spiritual transcendence. These homos are helplessly drawn back to the world as it is – they lack faith in the idea of a final unity between individual pleasure and collective experience, and yet they pursue the fantasy of such a unity all the same. Far from being socially disengaged, such an expression speaks to the conditions of our existence from a register beyond the scope of politics: the persistence of a loving attachment to the world becomes a furious index of the world’s fundamental inadequacy to live up to what it should be. Such a vision of the world rejects messianic thinking: it accepts a certain inescapable negativity inherent to subjective experience, and yet, rather than attempt to transcend such a negativity, it chooses to embrace the doomed joys of artifice and perpetual longing.

I’ve gotten ahead of myself. “Against Nature” was infamous before its doors had even opened. Widely rumored to be an “anti-ACT UP” show – a claim which was never put forth by any of the show’s participants, several of whom were themselves ACT UPers – Cooper and co. quickly earned the scorn of both local and national art critics. As one LA Weekly review quipped,

[Cooper and Hawkins] want to reestablish the exuberant Dionysian eroticism of yore, but they’ve set about it by eclipsing any tracings of AIDS: nothing of the fever of the health debates nor of the warfare of the Establishment upon the gay community – but lots of GQ torsos … this kind of response only endorses the opposition. [10]

Queer Nation took the outrage off the page and into the street, staging a die-in on the show’s opening night. While they made no public comment during the show’s run, Cooper and Hawkins would clarify their stance several years later in a memo (it is unclear to what extent the memo was made public), writing, “Ingrained in ‘Against Nature’ was a reaction against contemporary art-hating activism, the kind heralded by such critics as Douglas Crimp and entrenched in a kind of, ‘put down your paintbrushes; this is a war’ production.” [11] Cooper and Hawkins reject Crimp’s insistence that art should represent “supposed hard fact and indisputable truth,” a position which they take as effectively discarding all “gay” art which fails to live up to such ideals as inherently “phobic, unengaged, and removed from social significance or import.” [12]

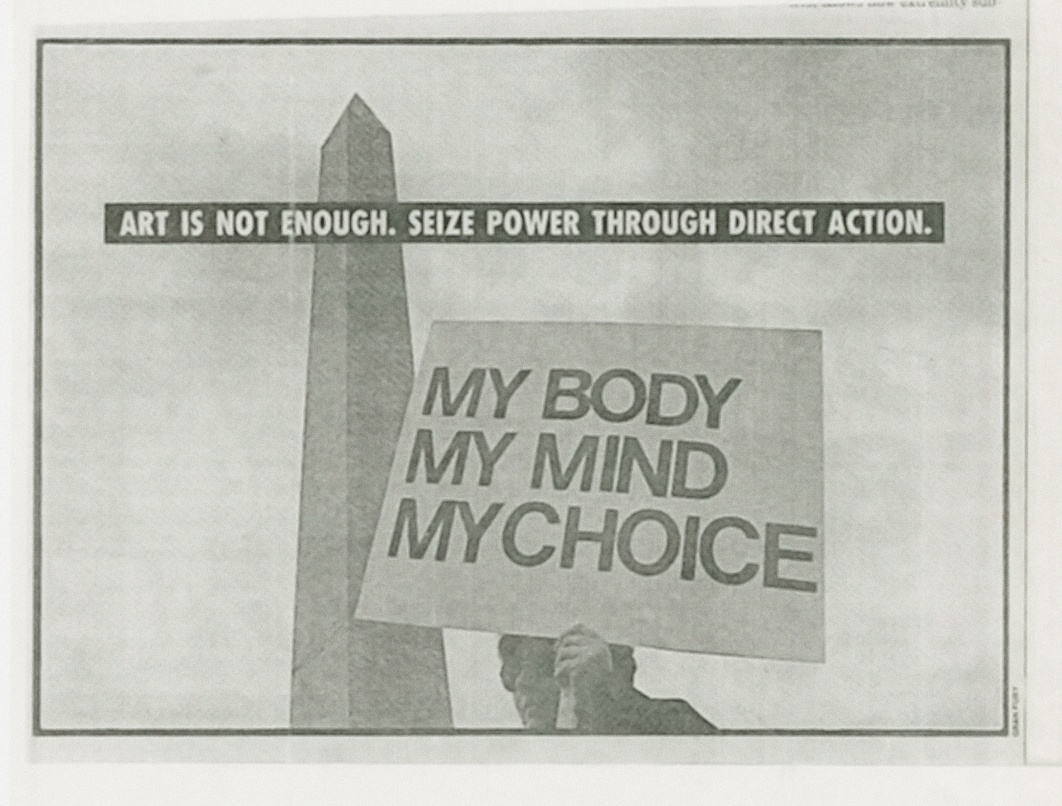

Gran Fury, „Art Is Not Enough“, 1988

Crimp was “Against Nature”’s harshest critic. In the essay “Good Ol’ Bad Boys,” Crimp accuses the show of embodying a perversely childish form of political incorrectness through the repeated use of the term “homosexual” in press materials (as opposed to “gay” or, more confusingly, “faggot”), a decision which Crimp chalks up to the antics of a few vindictive brats clamoring for art world power. It is important to note that Crimp makes no comment on the actual work exhibited. Crimp’s primary contention with the use of “homosexual” is that it posits a false image of gay identity as a fixed, essentializing condition, as opposed to a politically constructed – and thus contestable – concept. In what could be fairly characterized as a motivated act of playing dumb, given Crimp’s sharp critical intellect, he writes,

the curators of “Against Nature” make no arguments for their positions, and we are therefore left to surmise that to call the exhibition ‘a show by homosexual men’ is merely a means of registering the refusal to be politically correct. … The curators resolutely refused a public discussion of the exhibition, just as they refused to stake out a clear position in the catalog. [13]

In Crimp’s estimation, insofar as “Against Nature” failed – or refused, more likely – to stake a clear political position, it fell short of lending itself to a direct, literal interpretation of its engagements with homoeroticism, tossing yet another stick upon the faggot bundle of decadent, “anti-activist” fictions obscuring the truth of the matter regarding AIDS.

This was not the first time Crimp had articulated such a strong position about the interplay between aesthetics and power: as he put it in 1987, “art does have the power to save lives, and it is this very power that must be recognized, fostered, and supported in every way possible …we need cultural practices actively participating in the struggle against AIDS.” [14] While Crimp’s writing on AIDS eventually drove an enduring wedge between him and his fellow editors at October, it is helpful to understand his theoretical position here as an extension of the very same Foucauldian theory that he originally helped to bring to the fore of art criticism in said journal’s pages. Through essays including “The End of Painting,” Crimp had already developed a vision of the relationship between representation and power which took all modes of subjectivity to be inherently unfixed and thus, by extension, inseparable from the knowledge-forming systems that give them legible shape. This is directly articulated in his introduction to the October issue “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism”: “AIDS does not exist apart from the practices that conceptualize it, represent it, and respond to it.” [15] In the context of such a theoretical framework, every representation carries a distinct political dimension, either reaffirming the realities of those directly affected by AIDS or actively diverting attention from the cause. However inadvertently, Crimp’s faith in the possibility of overcoming the oppressive structures of his moment carries within itself the nascent trace of messianic thinking. In order to distinguish between harmful and emancipatory representations of AIDS, one must first have faith in the fundamental possibility of a better world: each expression is assigned social value in accordance with the degree to which it drives us either closer to or further away from the possibility of a future in which we are able to freely articulate and embody the truth of our subjective experience without impediment or misrecognition. Disconnection is dragged to the surface of material reality, taking on the definite shapes of political enemies; subjective negation loses any existential or ontological underpinning, reduced to the lasting affect of a cultural battle over who, or what, possesses a monopoly over the representation of reality.

Crimp’s deconstructionist framework found its corollary in the spread of AIDS itself. AIDS, as Paula Treichler put it, was an epidemic of signification, the first truly “postmodern” disease. [16] Its spread revealed a fragmented, rhizomatic vision of homosexual contact, linking street hustler to Wall Street businessman to married New Jersey lawyer to Downtown dancer. AIDS not only shattered any liberal illusion of an inherent moral or cultural cohesion to homoeroticism but also simultaneously provided convincing evidentiary fodder for the very deconstructionist theories that were taking hold in the more intellectually oriented wings of AIDS activism’s ranks. If the writing of theorists like Crimp provided a tentative framework for understanding the political stakes of representation during the period, then the decentralized, multimedia-savvy tactics of AIDS activism put this theory to practice, expounding upon a new vision of political action as the living embodiment of postmodern fragmentation. Crimp, in turn, would codify the theoretical framework undergirding AIDS activist aesthetics through such texts as AIDS Demographics, pulling directly from the social-practice-based work of collectives like Gran Fury in order to elucidate a theory of the relationship between activist representation and the affectation of social change. While the context of the moment established the contingent conditions necessary for both Crimp’s cultural theory and AIDS activist practices to arise independent of one another, said theory and practice would find not only their respective justifications but also their fundamental means of self-articulation in one another, begetting a mutually reinforcing unison of analysis and action that insulated itself under the alibi of an unforced, self-justifying response to crisis culture.

„Against Nature“ (Nayland Blake), Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 1989, installation view / Ausstellungsansicht

This shift was by no means constrained to the localized tiff between Crimp and “Against Nature,” nor was it limited to the question of the homosexual body. Other shows were subjected to a comparable line of critique: a New York group show entitled “Erotophobia” (Simon Watson Gallery, 1989) – a name which carries within itself a similarly explicit anxiety around, or perhaps confused infatuation toward, pleasure and the sexualized body – faced the same kinds of accusations. In her review for Artforum, Catherine Liu writes, “Male homosexuality was certainly the best-represented sexual theme, but it was the proliferation of penises that created the impression that this show was really about cocks” [17] (unlike “Against Nature,” “Erotophobia” did not exclusively constrain itself to showing work by gay men). Conversely, other exhibitions, such as the Nan Goldin-curated 1989 (a conspiratorial mind might be drawn to the recurrence of this single year) Artists Space show “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” became a cause célèbre amongst AIDS activists. “Witnesses” rose to prominence in no small part due to the NEA’s decision to temporarily pull funding in reaction to what it deemed to be a particularly objectionable (read: “political,” as opposed to “artistic”) catalogue essay contribution from David Wojnarowicz, in which he called Cardinal Joseph O’Connor (a leading figure in the Catholic church’s attempts to promote lethal disinformation about the spread of HIV) a “fat fucking cannibal.” [18]

The sensation surrounding “Witnesses” arose in part due to the ease with which it rendered legible the social dynamics undergirding AIDS activism’s understanding of the politics of representation: because Wojnarowicz was an HIV-positive gay man, his self-expression constituted within itself an inherently political gesture. The NEA’s reprimand only confirmed, rather than complicated, what so many already knew: representations of gay life that fell out of a narrow, predetermined set of acceptable limitations constituted a direct, tangible affront to the balance of institutional power. Rather than argue that Wojnarowicz’s work should be read in fundamentally artistic terms, most of the NEA’s critics not only doubled down on the idea that Wojnarowicz’s work was fundamentally political but also, by extension, asserted that it was the ethical imperative of anyone concerned with putting an end to the AIDS crisis to fight for such political expressions to flourish. Wojnarowicz, for what it’s worth, detested this newfound fame: in an interview with Sylvère Lotringer he recounts, “what was really frustrating in terms of how Artists Space dealt with me was that they reacted as if what I’d said, or what I embodied, was unbelievably radical.” [19] Later in the same interview, Wojnarowicz explicitly aligns his work with “Against Nature”: “Dennis Cooper was attacked by some activist philosopher [one can assume he means Crimp] because of what he writes, and because of a show he put together out in California called ‘Against Nature.’ As far as I’m concerned, he’s one of the most heavily political writers that captures the tone of this country.” [20] It’s not hard to see a practice of selective reading take shape. Subjective expressions are emptied of complexity, whittled down to the lowest common denominator of a shared homosexual identity: it does not matter that Wojnarowicz aligned himself with “Against Nature,” because, unlike Cooper, his work (inadvertently) made itself available to a type of contorted political interpretation. Context and sensibility become flattened into a one-size-fits-all analytical framework, one capable of making tidy distinctions between “good” and “bad” forms of sexual representation on the basis of their use-value to a continually hardening unity of theory and practice.

In their attempts to confront the theological moralism of the culture industry, AIDS activists adopted a death-by-one-thousand-paper-cuts strategy: they unleashed an endless litany of fragmentary representations and personal mythologies, eradicating any legitimacy to the notion of a single truth regarding AIDS. In doing so, they perhaps inadvertently erected a counter-theology of their own. In order to gain coherency – the strategic premium of all movements – every purposeful step toward representative inclusion, no matter how wide a net it casts, still requires the negative image of that which is excluded. AIDS activism countered with a theology of the infinitely expansive political voice: every self-representation, insofar as it could be put into literal relation with a political practice, bore responsibility for the articulation of a new world struggling to be born.

Exhibition catalogue / Ausstellungskatalog

It was not those who espoused the wrong politics, but rather those who, much like Cooper and co., espoused no coherent politics, who came to reside beyond the pale of such a theological framework. Accusations of negligent irreverence and decadence – those old queen-hating tropes – did not disappear under the new faith, but rather found a new home in representations of desire which could be discarded as baroque, delirious, irreverent, or too passively analytical. AIDS activism’s cultural battle, which began as an attempt to combat the deadly metaphors of mainstream reportage through a literal setting straight of the record, found itself in turn abstracted into yet another un-literal metaphor. Writing in the wake of May ’68s failure to bring about a lasting cultural revolution, Guy Hocquenghem reflected:

We lose hopelessly if we are blackmailed by revolutionary bias and accept the lowest common denominator: revolutionary politics as the phallic culmination of all local organizing. This universal currency makes all strategies interchangeable; this steady compromise between ideological imperialisms consolidates the revolutionary side like gold consolidates the bourgeois side, where we can count, measure, compare the forces of each. [21]

There is little need to rework such sentiments to fit our present situation: it is precisely this preemptive ideal of universal translatability, of a general reduction of subjective expression to the lowest denominator of political legibility, which is the lasting impact of AIDS cultural analysis – not on grassroots organizing directly, per se, but upon our ability to conceptualize representation as anything besides a metaphorical proxy for grassroots organizing.

What is to be done? It is imperative to avoid placing undo faith in the act of supplanting one metaphor with its natural antithesis – while this tactic offers catharsis through momentary clarity of vision and conviction, it can never amount to more in the long run than a continuation of an ineffective, ouroboros style of anticipatory criticism. Perhaps it’s time to revisit those prematurely abandoned ideals of artifice, melancholia, and impossibility embodied by such moments as “Against Nature” – not as a suicidal or defeatist expression of cynicism, but rather as a formal recognition that all movements must fail, that all movements must give way to metaphor and allegory. Such expressions stand to stake out a third position regarding the representation of pleasure, one which refuses to acquiesce to either the realm of antisocial artistic transcendence or the realm of naked political use-value. It seems unlikely that such binaristic thinking surrounding the representative stakes of AIDS and homoeroticism will loosen its grip on mainstream consciousness soon. That said, if we allow ourselves to recognize this imaginative dimness for what it is, we can also allow ourselves to simply disregard it as more business as usual, which is to say, as nothing worth much energy. This temporary peace of mind could buy us the time to imagine what a more expansive, novel approach to representation might look like in our present. Not one which dreams of supplanting or exposing the faults of that which came before it, but rather one which aims to disrupt the premium placed upon a universal translatability, or weaponization, of subjective representation; one which shirks the expectations of saying anything of lasting value regarding identity, politics, or the gritty realities of living; one which takes its farcical, imaginative nature as a byproduct of the negativity undergirding all subjectivity, and which thus goes about trying to express this negativity, or this failure to communicate clearly, with the greatest level of idiosyncrasy possible.

Ryan Mangione is a New York–based writer and editor at November.

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Richard Hawkins, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) Records, and Getty Research Institute, scan David Evans Frantz; 2. Gran Fury / public domain; 3. Courtesy of the Estate of Kevin Wolff and LACE; 4. Courtesy of Richard Hawkins, LACE Records, and Getty Research Institute, scan David Evans Frantz; 5. Gran Fury / public domain; 6. Courtesy of Richard Hawkins, LACE Records, and Getty Research Institute, scan David Evans Frantz; 7. Courtesy of Richard Hawkins and LACE Records

Notes

| [1] | I am indebted to Alexandra Juhasz and Theodore Kerr for their coining of the term “AIDS Crisis Culture.” Alexandra Juhasz and Theodore Kerr, We Are Having This Conversation Now: The Times of AIDS Cultural Production (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2022). |

| [2] | Douglas Crimp, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 64. |

| [3] | Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987–1993 (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2021), xx. |

| [4] | Ibid., xviii. |

| [5] | Dennis Cooper and Richard Hawkins, “About Against Nature,” in Against Nature, exh. cat., ed. Dennis Cooper and Richard Hawkins (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 1989), 4. |

| [6] | Dennis Cooper, “Dennis Cooper in Conversation with Ryan Mangione,” interviewed by Ryan Mangione, November Magazine, February 2022. |

| [7] | Richard Hawkins, “Notations Toward Deciphering Elements of Illness and Loss Through J. K. Huysman’s [sic] Against Nature,” in Cooper and Hawkins, Against Nature, 7–9. |

| [8] | Kevin Killian, “Cherry,” in Cooper and Hawkins, Against Nature, 20–23. |

| [9] | Dennis Cooper, “Dear Secret Diary,” in Cooper and Hawkins, Against Nature, 5–6. |

| [10] | Jan Breslauer, “Nature Morte,” LA Weekly, January 20, 1989. |

| [11] | Dennis Cooper and Richard Hawkins, “1994 Letter on Against Nature,” (October 1994), Box 5, Folder 132, MSS.085, Dennis Cooper papers, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York, NY. |

| [12] | Ibid. |

| [13] | Douglas Crimp, “Good Ole Bad Boys,” in Melancholia and Moralism (MIT Press, 2002), 112. The essay first appeared as a conference paper, delivered in March of 1989 at Ohio State University. |

| [14] | Douglas Crimp, “Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” in Melancholia and Moralism (MIT Press, 2002), 32–33. |

| [15] | Douglas Crimp, “Introduction,” in “AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism,” themed issue, October 43 (Winter, 1987), 3. |

| [16] | Paula A. Treichler, How to Have Theory in an Epidemic (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 1999). |

| [17] | Catherine Liu, “Erotophobia,” Artforum 8, no. 2 (October, 1989), 176–77. |

| [18] | David Wojnarowicz, “Postcards From America: X-Rays From Hell,” exh. brochure, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (New York: Artists Space, 1989). |

| [19] | David Wojnarowicz, interviewed by Sylvère Lotringer, David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years on the Lower East Side, ed. Giancarlo Ambrosino (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2006). |

| [20] | Ibid. |

| [21] | Guy Hocquenghem, “Volutions,” in Gay Liberation After May ’68, trans. Scott Branson (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 7. |