Amber Jamilla Musser has coined the concept of brown jouissance in reaction to the mechanisms of oppression that Hortense Spillers described in 1987 as “pornotroping,” which strips Black people of their subjecthood and turns them into objects exposed to sexualized violence. Brown jouissance too is engendered by these structures – but it also transcends them, turning to forms of pleasure that, thanks to intentional obfuscations, prove more resistant to subjugation. Building on the theoretical genealogy of her analytical terms, which also draw on the thinking of Jacques Lacan and Sigmund Freud, Musser illustrates their emancipatory potential with examples from contemporary art and culture.

In Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1645–52) Teresa of Ávila is captured mid-swoon with eyes closed and head tilted back, facing an angel with a gold spear. Her clothing is arranged in sumptuous folds, light envelops the scene courtesy of a stained-glass window, and sculptural gold rays cascade from the ceiling. The work was commissioned in January 1647 by Cardinal Federico Cornaro to honor Teresa, who had been canonized in 1622. Drawing on a passage from her autobiography in which she narrates in exquisitely sensual detail the ecstasy of her soul communing with God, Bernini translates Teresa’s rapture into stone, the luxurious marble, especially, lending depth to the comingling of pleasure and pain that Bernini carves onto her face. In Teresa’s narrative of the encounter, she associates the overwhelming nature of the experience with the presence of God, positioning it beyond the physical and into the realm of the spiritual:

The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God. The pain is not bodily, but spiritual; though the body has its share in it, even a large one. It is a caressing of love so sweet which now takes place between the soul and God.

Yet, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan focuses not on the religious aspects of her rapture but its physical nature, equating the ecstasy portrayed by Bernini with orgasm, famously using The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa to describe feminine jouissance. He says, “You only have to go and look at Bernini’s statue [of Saint Theresa] in Rome to understand immediately that she’s coming, there is no doubt about it.” Despite the certainty with which Lacan describes her orgasm, he cannot discern its cause: “And what is her jouissance, her coming from?” While the unknowability of her jouissance is central to Lacan’s conceptualization, the link to orgasm adds to the mystique that surrounds pleasure, especially when it is linked to feminine sexuality (that which is definitionally not the phallic). Feminine jouissance, itself, is meant to be mysterious. Unlike the jouissance that comes from self-shattering (phallic jouissance), it is jouissance that purportedly comes from the fulfillment of the desires of the other, which are unknowable because they fall outside of the phallic order, which is to say that both the feminine and the jouissance related to feminine desires are unintelligible within the symbolic order. In his elaboration on the concept, Néstor Braunstein writes, “Its model is surfeit, a surplus, the supplement to phallic jouissance of which many women speak without being able to say exactly what it consists of, like something felt but unexplainable.” In Lacan’s framework, feminine jouissance is incomprehensible because it is outside the symbolic and is therefore fundamentally unknowable and untranslatable – these are sensations that might be witnessed, but not explained. Importantly, as Jacqueline Rose argues, this inability to know the feminine lies at the heart of sexuality for Lacan because wanting to know (and the constant inability to satisfy this want) lie at the heart of desire.

In her critique of Lacan’s formulation of the feminine and feminine jouissance, Luce Irigaray argues that much of this mysteriousness can be attributed to the fact that Lacan is not engaging with Teresa’s words but Bernini’s interpretation, which adds yet another layer of phallocentrism to the endeavor. Further, Dany Nobus argues that Lacan’s focus on the face as locus of pleasure is especially symptomatic of Lacan’s displaced interpretation because it is the only thing that Teresa cannot describe. Nobus’s argument about the significance of the face itself recalls both Linda Williams’s and Annamarie Jagose’s analyses of the ways in which visual signifiers of female orgasm are assumed to reside on the face, rather than elsewhere in the body.

Anecdotally, I want to attribute some of Lacan’s uncertainty about the Other’s desire to the fact that he first saw Bernini’s sculpture on his honeymoon in 1934, a time when the newlyweds would likely still have been getting acquainted with each other’s preferences. But Lacan’s bafflement finds resonance with the seeming unending investigations into the clitoral orgasm – does it have an evolutionary purpose? Why does it exist? As Irigaray suggests vis-à-vis the feminine and feminine jouissance, some of this lack of knowledge comes from phallocentrism, which accounts for anemic funding for research on the topic as well as a historic lack of curiosity from a male-dominated field. As Rose points out, the mystification of pleasure has significant consequences within Lacan’s own understanding of sexuality – its ungraspability makes desire possible because it illustrates the impossibility of knowledge (and therefore possession). Yet, theorizing pleasure by tracing the contours of where it might emerge also means that its actual presence is not only external to these dynamics but superfluous.

Moreover, Lacan’s under-investment in pleasure differs markedly from Sigmund Freud’s attention to the topic, especially in early work that argued that pleasure motivated much human behavior. The opening paragraph of 1905’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality makes the centrality of pleasure explicit by positioning it as a need. Freud writes,

The fact of the existence of sexual needs in human beings and animals is expressed in biology by the assumption of a ‘sexual instinct,’ on the analogy of the instinct of nutrition, that is of hunger. Everyday language possesses no counterpart to the word “hunger,” but science makes use of the word “libido” for that purpose.

In a footnote added to a later edition of the text, Freud suggested that the German term Lust might be better than hunger. This word, meaning appetite, desire, or zest, connotes need, pleasure, and urgency. It also conveys the closeness of sexuality, life, and pleasure in the Freudian schema of 1905. In part, this attachment to pleasure can be traced to Freud’s interest in child development. In extending sexuality to infants, he focused on pain and pleasure, the only analytic axes that he felt were translatable to infants. Since infants were assumed to not yet be cognizant of their enmeshment in a social framework, sexuality could not be understood on those grounds. In this, Freud also differed from previous theorists, who saw most perversions as biological manifestations of broken social norms. Infant sexuality, then, was marked not by social arrangement, but by pleasure, which became the basis for Freud’s theory of sexuality. Freud’s concept of pleasure, however, was multi-faceted – the pleasure gained from orgasm was different from the pleasure gained from eating. What is significant is that he lumped them together as forms of the same desirable emotional experience. In this schema, one is always working for pleasure.

And so, in the space between Freud and Lacan, I am curious about how to think about pleasure – is it extraneous? Is it a need? Drawing a line between Lacan’s theorization of phallic jouissance as that which shatters the idea of the self and Hortense Spillers’s discussion of the ways that the transatlantic slave trade stripped personhood from Black people, I develop the concept of brown jouissance, which hovers between these poles. I argue that brown jouissance emerges from the objectifying processes of racialization, but it moves beyond the parameters of woundedness toward intimacies and pleasures that resist capture. The parallels with the mysteries of Lacan’s feminine jouissance are clear; yet, what is important about brown jouissance is that I understand its process of mystification as a deliberate form of obfuscation produced by expressivity rather than a matter of the interpretive confusion that Lacan describes.

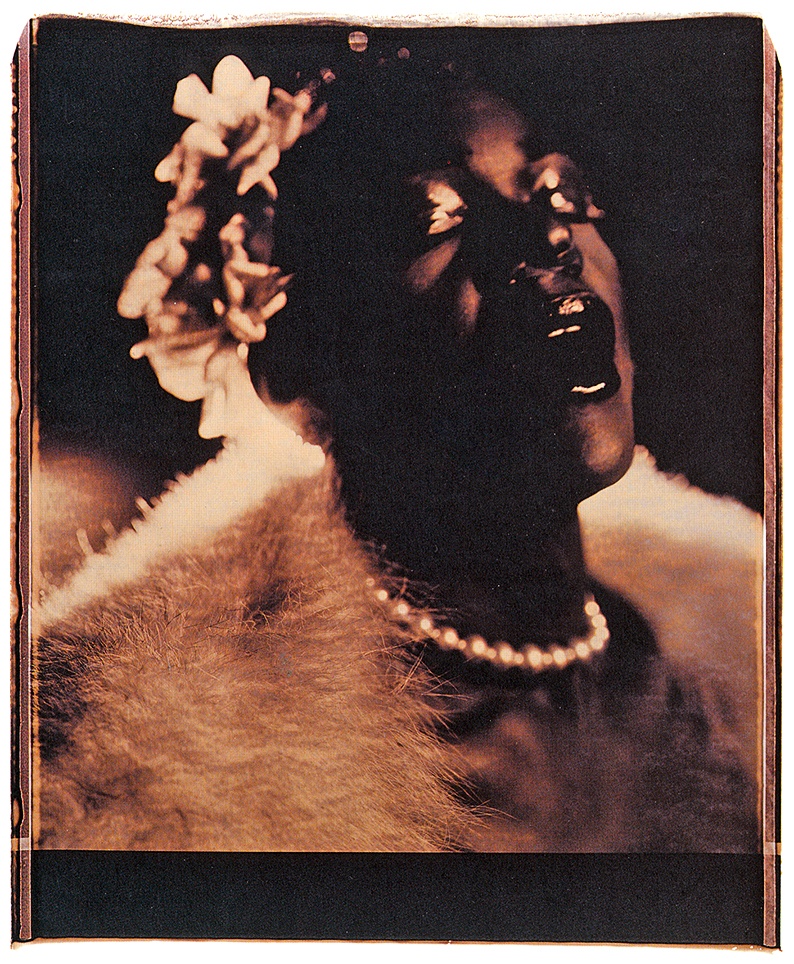

We can, for example, find brown jouissance in Lyle Ashton Harris’s performative self-portrait as Billie Holiday, Billie #21 (2002), in which Harris emulates Holiday through clothing, posture, and cosmetic tape. In the Polaroid, it is easy to mistake Harris for Holiday: his head is thrown back in what looks like ecstasy, with his mouth open and a gardenia tucked behind his ear. Even Harris’s emoting of joy, sorrow, and dignity feels familiar. There is also a specific excess to the photograph, which I locate in the fuzz of the fur that Harris wears and in the shine that gleams on his pearls and lips. What I call brown jouissance is in Harris’s rapture at his proximity to Holiday and his embodied working through of her hunger, even as this citation also evokes Holiday’s own addiction and suffering from racism and misogyny. On the one hand, pleasure in this scenario might feel confounding; on the other hand, we might also understand the ways that pleasure for both Holiday and Harris serves as a survival mechanism. The mix of pleasure and pain that Teresa describes as spiritual union here become a mode of working through the difficult present. Is such a practice really optional? Might we see that pleasure as necessary, even when it might be labeled excess?

In a similar vein, Jillian Hernandez traces the importance of taking pleasure in excess as a way to negotiate the politics of respectability in her study of the adornments chosen by Latinx women and girls in working-class Miami. Superficial embellishments – long hair, long nails, and push-up bras – not only mark these femininities by race and class but also provide sources of pleasure. These pleasures are multiple. These accessories help women feel beautiful by allowing them to own (and solicit) the objectifying gazes that come their way. They also signal an investment of time and resources in the self, which is a result of believing in one’s value. Hernandez attaches pleasure to these forms of self-making because they confront the myriad forms of violence and dismissal that these women face with an alternate value system in which their wants are foregrounded. While respectability politics operates through an attempt to discipline people’s pleasures – making pleasure seem inaccessible or sullied – Hernandez’s work shows the ways that pleasure remains an abundant resource. Pleasure here is not just about survival; it is also a portal into another way of living that does not prioritize function or conformity.

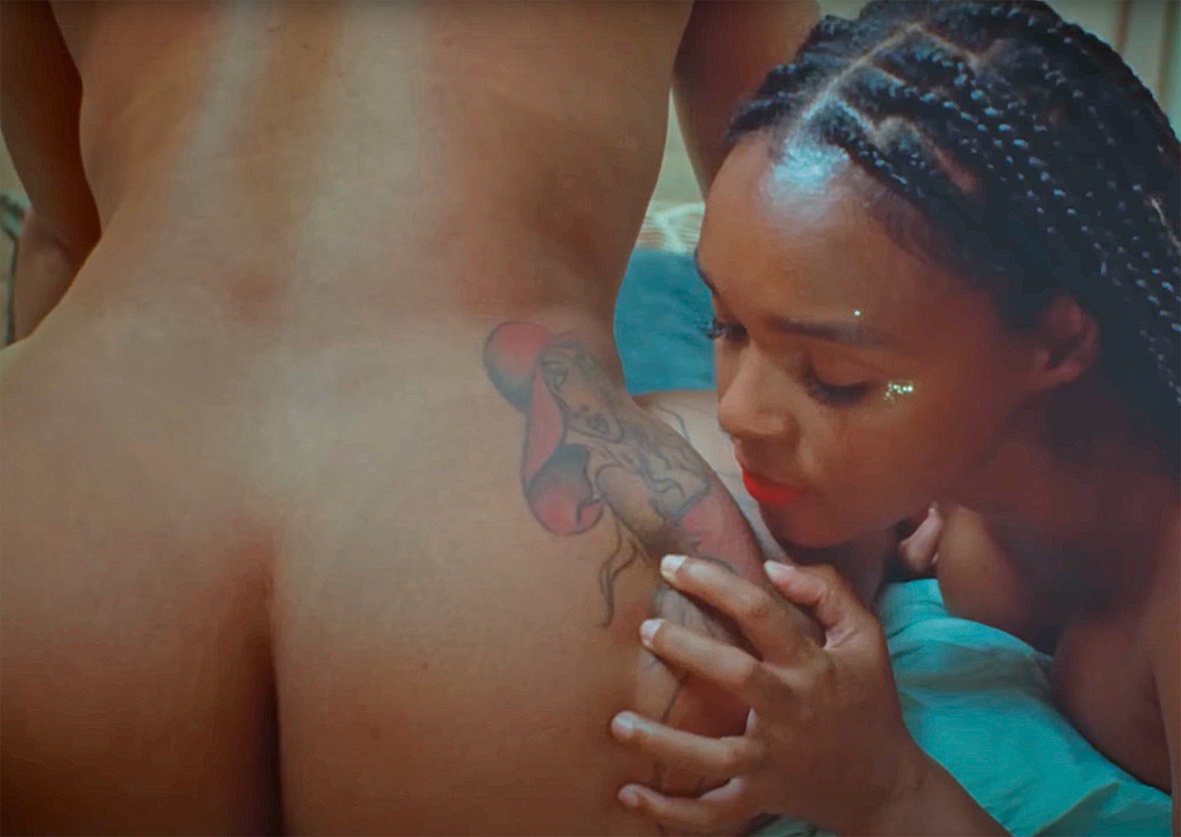

All of this, finally, brings me to Janelle Monáe and their recent album, The Age of Pleasure (2023). The album is joyfully and explicitly queer. Its videos, including “Lipstick Lover” and “Water Slide,” show Black people of many genders dancing, eating, kissing, and swimming. In “Lipstick Lover” we are treated to shiny bodies gyrating in bathing suits, painted bodies in thongs, party scenes, make-out scenes, food scenes, sex toys, wet T-shirts, tiny shorts, Monáe licking a shoe, Monáe eating said shoe, Monáe caressing and kissing a bare tattooed ass, Monáe masturbating, Monáe in a Pokémon onesie, Monáe diving into a pool. Against these visuals, Monáe sings about what turns them on: “I like lipstick on my neck” and offers instructions to augment pleasure: “leave a sticky hickey in a place I won’t forget.” This is pleasure in excess: flouting the norms of respectability by knowing precisely what will provide pleasure and in making pleasure central rather than marginal. Not incidentally, the video was filmed at Monáe’s residence (Wondaland West) in Los Angeles, something that allows us to see that pleasure is not being represented, it is being made as we watch.

This is also pleasure as a world order, which is where I find the brown jouissance in Monáe’s performance. It is not just that Monáe is reveling in their own pleasure but that this pleasure is tethered to an invitation to experience life differently. What we see in the videos need not be a supplement but the primary stuff of living – not as future potential, but as here and now. Omise’eke Tinsley pairs Monáe’s turn to pleasure with their recent disclosure of their obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) diagnosis in Rolling Stone. OCD, Tinsley argues, is difficult because one focuses on the myriad possibilities that may arise, forcing one to live in the future rather than the present. Pleasure, for Monáe, however, is about exploring the present: “It’s beautiful that I have a title called The Age of Pleasure because it actually re-centers me. It’s not about an album anymore. I’ve changed my whole fucking lifestyle.” What I want to take from Monáe is that this re-centering is not about need or compulsion, but about a different orientation to time and space. Listening to Monáe, perhaps as Lacan did not listen to Teresa, might reveal a whole new episteme. As Tinsley writes,

What if we could all bare the curves and twists of our minds as openly as lovers bare their asses and tits in ‘Lipstick Lover’? What if we took Monáe’s reggae inspiration seriously and really, really emancipated ourselves from mental slavery – really let ourselves free our minds?

Amber Jamilla Musser is a professor of English at the CUNY Graduate Center. Her research lies at the intersection of critical race theory, queer studies, and black feminism. She is the author of Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism (New York University Press, 2014), Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance (New York University Press, 2018), and Between Shadows and Noise: Sensation, Situatedness, and the Undisciplined (Duke University Press, forthcoming 2024).

Image credit: 1. Public domain; 2. Courtesy of Ayana Evans, photo Ayana Evans; 3. © Lyle Ashton Harris, courtesy of Salon 94 and David Castillo; 4. Courtesy of Crystal Pearl Molinary and Jilian Hernandez; 5. Courtesy of Janelle Monáe and Atlantic Records

Notes