In the 1970s, two museums opened on the west coast of the land claimed as Canada, their founding having been a prerequisite for the restitution of parts of the Kwakwaka’wakw’s Potlatch collection. The complex history of the dispossessions sanctioned as part of Canada’s colonial policy, as well as the significance of repatriation within Kwakwaka’wakw social structure, is laid out in anthropologist Alexandra M. Peck’s contribution, which also highlights a specific conception of individual ownership and collective property. As props and regalia, the objects frequently changed hands via the Potlatch practice. Each exchange brought along with it an increase in value. This inner-societal mobility also had a stabilizing function: the handovers bore testament to important political and private agreements. The absence of the objects, logically, thus led to disequilibrium – and their museumization-linked reintegration remains incomplete, even after half a century.

The Indian Act and Potlatch Ban

Although ignorant of many aspects of Indigenous life, Canadian settler colonists recognized the importance of potlatching forKwakwaka’wakw society. From their “enlightened” perspective, potlatching was proof of Indigenous “instability” and “immorality.” Relinquishing all of one’s possessions to an audience did not align with capitalism’s merit-based wealth acquisition, and week-long potlatch festivities were viewed as undeserved vacations that kept participants from reliably holding jobs in the capitalist economy. To an uninitiated settler-colonial observer, potlatches were loud, ostentatious, and frenetic – traits that threatened attempts to transform Kwakwaka’wakw individuals into “civilized,” Christian subjects.

In 1876, Canada enacted the Indian Act, a broad piece of legislation that prohibited Indigenous individuals from (among other things) wearing cultural regalia, voting, speaking Native languages, or fundraising for legal aid. The act’s Potlatch Ban clause sentenced violators to prison for performing and gathering in large groups or exchanging gifts. During this time, potlatching went underground, with events disguised as holiday gatherings (Christmas, for example), to distract from Indigenous affiliations. Abandoning the potlatch risked severing important ties to the past and endangering one’s hereditary privileges – features that symbolized the very nature of Kwakwaka’wakw life.

The Potlatch Collection’s Origins

In 1921, Chief Dan Cranmer (1885–1959) hosted the largest potlatch recalled by Kwakwaka’wakw attendees. It was attended by over 400 guests and lasted nearly a week, with witnesses receiving generous reimbursement. This potlatch was not a festive event but an administrative act: Cranmer had separated from his wife, Emma, and Kwakwaka’wakw law required he return wealth and privileges to Emma’s family. An indulgent host fulfilling his legal duties, Cranmer had returned all of his ex-wife’s property and parted with most of his own belongings. As this potlatch suggests, repatriation – like property – was not a foreign concept to the Kwakwaka’wakw. Instead, restitution was integral to society.

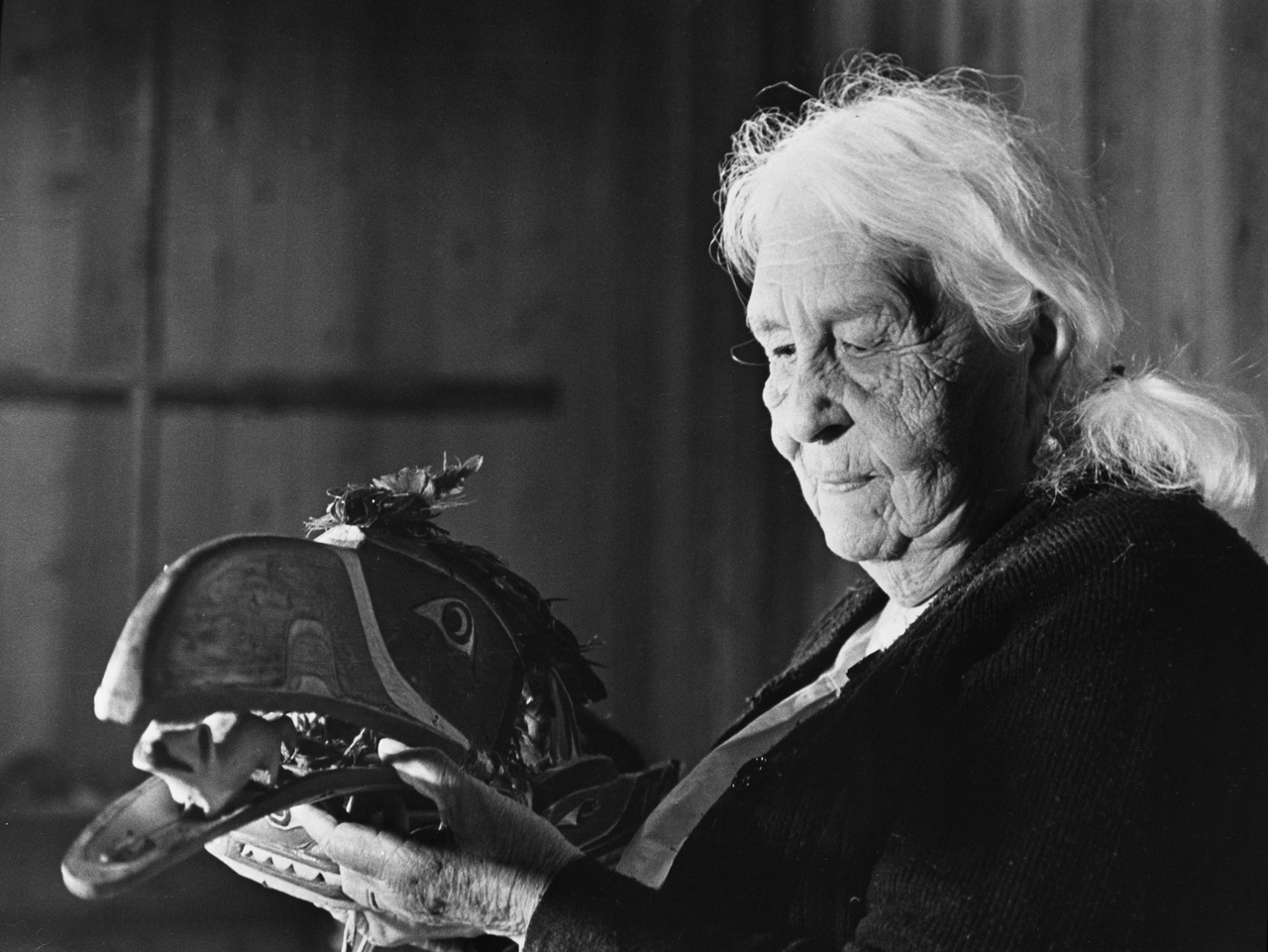

Colonial authorities quickly intervened, charging nearly 45 participants. Some pleaded guilty, while others denied that Canadian law applied to Kwakwaka’wakw sovereignty. Labeled as criminals, individuals had two options: suspended jail sentences in return for their respective village’s potlatch items, or imprisonment. Many opted for the former and “weeping, as if someone had died,” watched as a barge disappeared into the horizon, loaded with masks, dishes, and regalia. Harry Assu remembered his Elders lamenting, “‘There is nothing left now. We might as well go home.’ When we say ‘go home,’ it means to die.” Attempting to make sense of this trauma through a Kwakwaka’wakw lens, potlatch participant Agnes Alfred (1890–1992) remarked, “We were free because […] the masks had paid our way out of jail.”

Cranmer did not predict that his gathering, intended as a legal transfer of property, would prompt the (il)legal seizure of over 650 potlatch goods – today, notoriously known as Canada’s “Potlatch Collection.” Upon confiscation, so-called Indian agents displayed the items at the Anglican Church in the Kwakwaka’wakw community of Alert Bay, charging admission for tourists, anthropologists, and collectors to view or photograph the overwhelming assemblage. Pieces from the Potlatch Collection swiftly left Kwakwaka’wakw territory, with masks handpicked by collectors, donated to museums around the globe, or sold to other institutions. Like the Cranmers, the Potlatch Collection had suffered a separation.

Confiscation versus Collecting

The Potlatch Collection’s colonial history mirrors a phenomenon familiar to Native communities of that era: the exodus of Indigenous material culture from local settings into museum displays. Early anthropologists practiced salvage ethnography, the collecting of “artifacts” from Indigenous interlocutors whose societies were thought to be doomed to extinction. For government agents who prosecuted potlatch attendees, the goal was quite different: to promote cultural decline. Aware of this discrepancy, Kwakwaka’wakw leaders welcomed anthropological forefather Franz Boas (1858–1942), as long as he did not

stop our dances and feasts […]. We do not want to have anybody here who will interfere with our customs […]. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law, we shall observe ours.

Through Canadian eyes, the Potlatch Collection consisted of symbolic trophies won during a heroic battle between Kwakwaka’wakw and non-Native entities under the Indian Act. The objects were now imbued with elevated status stemming not from their Indigenous significance but rather from their role in Canadian history. Ironically, the collection provided physical evidence that the Kwakwaka’wakw had not been subsumed by settler colonialism, nor were they the disappearing race described by anthropologists. However, the mode of collecting – mass confiscation with scant regard for the objects’ owners, makers, or meanings – bolstered the narrative that the items were ancient, untraceable relics rather than contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw belongings. The deliberate lack of provenance aligned with anthropology’s salvage ethnography theory. After all, if the previous proprietors of the Potlatch Collection had conveniently “vanished,” no impetus existed for repatriating the possessions of an extinct culture.

The Potlatch Collection Today

As of 2023, the Kwakwaka’wakw operate two museums: the U’mista Cultural Centre and the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre, both founded in the 1970s as a stipulation for the return of a majority of the Potlatch Collection from museums worldwide. Both institutions’ names reference ownership and repatriation, with U’mista denoting the Kwakwaka’wakw concept of something arriving home safely, and Nuyumbalees referring to potlatch melodramas that communicated communally held rights. Much has been written about the Potlatch Collection’s turbulent past, but little scholarship exists on repatriation’s repercussions for contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw communities or what roles the objects play today.

Historically, potlatch accoutrements were deemed living entities whose energy risked depletion if not allowed to rest between potlatches. However, the repatriation of the Potlatch Collection to U’mista and Nuyumbalees affects the treatment of items. No longer are the masks wrapped and stored to preserve their sacred power. Instead, the objects are exhibited in these two Indigenous museums – sites established as a requirement for repatriation – yet the institutions curiously lack significant signage or labels about the items’ functions within a Kwakwaka’wakw milieu. In museums that serve both Native and non-Native visitors, one wonders if this lack of public information about the collections is an attempt to subvert the colonial gaze. Exhibited on small pedestals, the masks stand silent, their bulging eyes and gaping mouths observing as museum visitors inspect the pieces with little knowledge of what they signify. This institutional silence is an Indigenous form of refusal, implying that some forms of Kwakwaka’wakw knowledge should remain private, even if the items themselves now occupy a secular arena.

Cognizant of the Potlatch Collection’s past, Kwakwaka’wakw anthropologist Gloria Cranmer Webster (1931–2023) observed that, after the items had been “locked up for so long in a strange place [non-Indigenous museums] […] it seemed wrong to lock them up again.” However, the display of potlatch objects at U’mista and Nuyumbalees is more complex than meets the eye. The items remain housed in museums (albeit of a different type), yet they are afforded opportunity to circulate, a process that historically escalated potlatch goods’ value. For example, in 2011, U’mista facilitated a temporary exchange with the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, and, in more local settings, Kwakwaka’wakw proprietors borrow items for contemporary potlatching or models for replicas. Liberated from its dark past, the agential collection remains active within its community and enables Kwakwaka’wakw individuals to show “what cultural privileges they hold and what songs, dances and legends they can celebrate.” Because human interaction defines potlatch objects, this resocialization also serves to rekindle their identities, reinforcing the notion that items contain their own biographies and experiences.

Similarly, repatriation prompts the revival of certain cultural practices, as seen during potlatches hosted by U’mista when missing objects are returned. When Chief Mungo Martin (1879–1962) hosted the first legal Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch in 1952 (after the Potlatch Ban ended in 1951), it did not feature items from the Potlatch Collection. These belongings did not begin to be repatriated until the 1970s, with some items still absent today. When formerly missing objects are re-debuted at modern potlatches, they serve as mnemonic reminders of “dark and trying times” in Kwakwaka’wakw history and open the floodgates for emotions that were repressed as a result of shame or anger. The reintegration of objects is cathartic, as well as a way to honor past and contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw individuals and physically bring ancestral rights into the present.

Repatriation of the Potlatch Collection also raises questions about rightful Kwakwaka’wakw patrimony, with once-silenced possessions now offering recalcitrant opinions. Because the objects were traditionally linked to special social groups or families, specific Kwakwaka’wakw factions claim certain items as their own, sometimes revealing community conflict. U’mista elects to downplay these contentious issues, instead highlighting the Potlatch Ban and Canada’s history of Indigenous discrimination. By contrast, Nuyumbalees emphasizes rights and ranked status, integrating family photos into its exhibits to connect the repatriated materials to specific familial leaders and defend against accusations of false ownership. In exhibit texts, the museum subtly reminds readers that, when chiefly classes lost their positions because of “diseases, conversion to Christianity, and the threat of imprisonment, commoners unlawfully took the seats of distant noble relations.” This statement positions the museum as an authority, suggesting that some Kwakwaka’wakw descendants do not hold legitimate rights to potlatch items. However, the museum carefully does not directly accuse any particular party, reflecting the Kwakwaka’wakw value of proper behavior that is associated with nobility. The museum’s approach resists depictions of Native communities as egalitarian or harmonious, instead showcasing the “legendary Kwakwaka’wakw penchant for diversity and argument.”

Paralleling Victor W. Turner’s model of social drama (a four-step process), the Potlatch Collection has endured the infamous Indian Act (breach or disruption), forced displacement from its Kwakwaka’wakw proprietors (crisis), and repatriation from stagnant non-Indigenous museum collections to dynamic Indigenous cultural centers (redress), and is now experiencing a process of resocialization within the community (reintegration). Although the Potlatch Collection’s 20th-century history undoubtedly affects the ways in which Kwakwaka’wakw society approaches ownership and materiality, the collection’s items possess broader and deeper Kwakwaka’wakw significance. Just as ‘Na’mima possessions exist as the property both of past ancestors and of future generations, the Potlatch Collection is not solely defined by its present state. Within Kwakwaka’wakw society, they are living beings, amassing lifetimes of experiences, traumas, and joys. While the deleterious impact of the 1921 seizure and settler colonialism’s consequences cannot be denied, these events represent a bump – not a mountain – in Kwakwaka’wakw history that spans from time immemorial to the present day. The Potlatch Collection’s recent tribulations represent merely one aspect of its multifaceted identity. As complex objects with ever-changing familial stewards and shifting economic values, these resilient treasures possess multiple (sometimes competing) meanings accumulated from past, present, and even future pathways.

Alexandra M. Peck serves as the inaugural Audain Chair in Historical Indigenous Art in the Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory at the University of British Columbia. Her research combines museum studies, anthropology, and archaeology to emphasize the multitude of meanings possessed by precolonial Northwest Coast art, ranging from totem poles to wool weavings to ancient stone tools. She previously was a visiting scholar of Indigenous studies at the University of Minnesota’s Institute for Advanced Study, after earning her PhD in anthropology from Brown University in 2021.

Image credit: 1. Public domain, photo Edward S. Curtis; 2. Public domain / Vancouver Public Library, photo Albert Paull; 3. Courtesy of U'mista Cultural Centre, Alert Bay, B.C. CANADA, photo Vickie Jensen; 4. Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo Pierre-Selim Huard; 5. Public domain; 6. Courtesy of Christopher Grabowski

Notes