RIVER REBELLION Jadine Collingwood on the Black Reconstruction Collective at the Chicago Architecture Biennial

Zion Estrada and the Black Reconstruction Collective, “2,340 Miles from 1880,” 2023, video still

We begin with Pangaea. Through crackling static, found footage from an old documentary narrates the prehistoric cleavage of the earth’s crust that birthed the Mississippi River. Entropy and order, rupture and flow, these rhythms pulse through Zion Estrada’s short film 2,340 Miles from 1880, which traces the Mississippi’s connections to histories of Black resistance. The film premiered as part of UNMONUMENT CHICAGO: AFTER WORK, the Black Reconstruction Collective’s contribution to the 2023 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Organized by the artist collective Floating Museum and titled “This is a Rehearsal,” this iteration of the biennial celebrates the speculative capacity of architecture; as the vision statement explains, “Rehearsal invites new possibilities through open dialogue, creative invention, and a generative process of discovery to understand how hope and care can emerge in architecture.” [1] The biennial’s decentralized format engages sites scattered throughout Chicago, including Bronzeville – a neighborhood whose historic role as an incubator for Black art and creativity is perhaps unparalleled. Today, spaces like Blanc Gallery continue this legacy with an energetic exhibition program featuring a roster of both local and international artists. In the courtyard of the gallery, the Black Reconstruction Collective (BRC) installed a small industrial lift modified to serve as a flexible structure that can be adapted to various functions as needed – a lectern, newsstand, billboard, or projection screen, perhaps. As part of UNMONUMENT, the structure will eventually travel to a total of ten cities, where it will be activated by different projects. In Chicago, the lift was fitted with a projection screen around which people gathered for the premiere of the film 2,340 Miles from 1880.

A collective of Black architects, designers, artists, scholars, and activists, the BRC formed in 2021 as a response to the group’s participation in the exhibition “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition used the unfulfilled promise of racial equality embedded in Reconstruction as a starting point for examining the ways in which architecture and urbanism might transform the built environment. [2] While it positioned Reconstruction as a continuing project that might structure the imagination of contemporary practitioners, the ten invited participants found that the museum’s own institutional structures were inadequate to support their work. The group created the BRC to provide logistical and financial support to one another as they attempted to navigate, challenge, and stretch institutions. In their “Manifesting Statement,” the BRC commits to continuing the ongoing work of Reconstruction, declaring, that we “take up the question of what architecture can be – not a tool for imperialism and subjugation, not a means for aggrandizing the self, but a vehicle for liberation and joy. […] With this commitment to Black freedom and futurity, we dedicate ourselves to doing the work of designing another world that is possible, here, where we are, with and for us.” [3]

With this mission in mind, the BRC conceived of the unmonument, a framework for unwriting the past, challenging the inherited legacies of architecture, and activating the latent dreams of the seemingly closed annals of history. If monuments concretize, solidify, and reify the past, an unmonument might enable new possibilities for transformation inflected by multiple viewpoints, alternative futures, and speculative imaginaries. The AFTER WORK alluded to in the Chicago iteration’s subtitle both implies that there is work to do in the future and suggests that the future might come after work, in the leisure time that follows work stoppage. In this respect, the biennial’s focus on rehearsal serves as a fitting backdrop for the BRC’s project. While rehearsal is future-oriented, essentially practice for what is yet to come, it also relies on memory, enabling the transmission of the past. Might we then look back at Reconstruction as a rehearsal for the ongoing project of Black liberation? What might we learn, what energies might be restored, and how might we restructure the built environment? These questions take center stage in the film 2,340 Miles from 1880, in which the unfinished project of Reconstruction emerges from the rhythms of the Mississippi River, interweaving with imagery connected to histories of stoppage and flow, work and leisure, rationality and sensation.

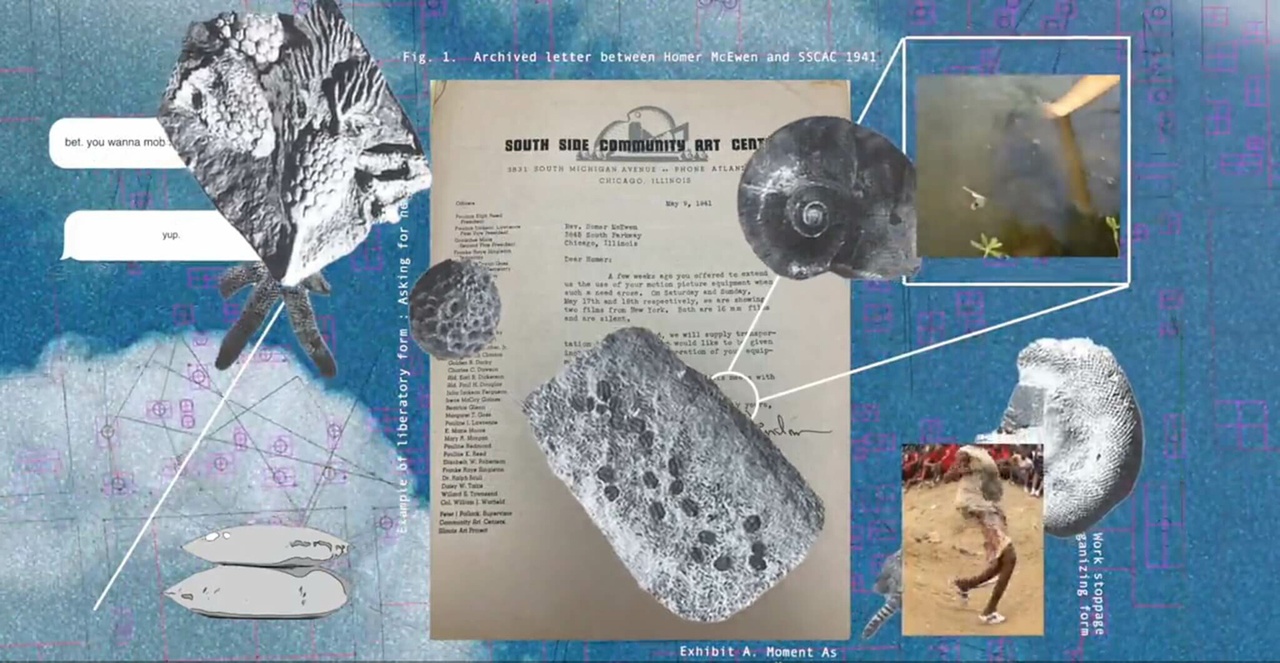

Zion Estrada and the Black Reconstruction Collective, “2,340 Miles from 1880,” 2023, video still

Made in collaboration with BRC founding member V. Mitch McEwen and with archival research by Cammy McEwen (no relation), 2,340 Miles from 1880 refers to the length of the Mississippi River and to a significant year of labor activity following the end of Reconstruction. Like the river, the film’s layered imagery twists and meanders, widens and narrows, gushes and trickles to weave together a narrative of the rebellions organized by plantation workers in Louisiana, the Great Migration of Blacks to northern cities such as Chicago, and the speculative imagination of leisure enabled by these collective moments of refusal. The project began in the archives of the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, where the group uncovered the records of Homer McEwen (1913–1985), V. Mitch McEwen’s great uncle. A Congregational minister in the southern United States, Homer McEwen was active in various civil rights and labor movements, and he was also an educator and writer. Documenting the Louisiana Farm Labor Strikes of 1880, he uncovered an overlooked history of active resistance, in which peaceful work stoppages challenged the plantation system. Writing in 1938, McEwen felt there was much at stake in his project; in a letter that appears in the film, he laments that researchers have disregarded these materials “partly through a subconscious (?) attempt to belittle Negroes.” Just a few years prior, W. E. B. Du Bois published Black Reconstruction in America: 1860–1880, a tome aimed at dismantling the myths of Reconstruction, which had spun a false tale in which emancipated Blacks were deemed responsible for their continued oppression in the United States. Like Du Bois, Homer McEwen recovers the lost narrative of Black resistance, constructing a history from the margins, the unsaid, the unfinished, and the speculative consideration of what might have been.

In 2,340 Miles from 1880, typewritten pages of Homer McEwen’s research are interspersed with footage of floods overtaking residential neighborhoods, public housing projects being demolished, photographs of families migrating north, Chicago census maps, news reports of an oil rig explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, a US Army Corps recruitment poster, coverage of the Watts Rebellion, the unrest in Minneapolis following the murder of George Floyd, a fast-food employee walkout during Covid, and several farm labor strikes throughout history. With the rapid pacing of the film, these images and words bleed together, superimposing in the viewer’s consciousness a continuous chain of references and sensations that sum up to a whole greater than any one part. Yet the corporeal impact of the film owes as much to the sonic as it does to the visual. The film’s soundtrack begins quietly with a syncopated click that speeds up and slows out of step with recorded sounds of the river trickling, bubbling, and dripping. These sounds transition into pulsing binaural waves – a sonic phenomenon in which two similar tones produce an auditory hallucination of a third tone that has been purported to have a calming effect on the listener’s nervous system. Against these quieting rhythms, the film incorporates the explosive sounds of buildings being demolished for urban renewal, a few vibrating bars of soul music, and the swelling voices of gospel singers. Racing across the screen, words and images accumulate multiple meanings and associations – the undulating waves of the river and the waves of hair under a durag, the eroding edges of the river and the laid-down edges of baby hair, the flow of the river delta and the flow of Delta sorority sisters dancing. Still photographs, scrolling text, and moving images progress slightly out of step with the film’s sonic rhythm. As a result, image and sound seem to vibrate in the viewer’s body, creating a sensation of motion that parallels the movement captured in the film – the migration of people north, the displacement of populations by disaster or gentrification, and the refusal to move represented by labor strikes. While the intensity of these moments is felt viscerally, underlined by the intermittent boom of a wrecking ball, moments of uplift – the frenetic energy of a death drop, the skillful plaiting of hair, the timbre of a soulful voice, the delight of catching a fish – channel the joyousness of bodies in motion.

“The Black Reconstruction Collective: UNMONUMENT CHICAGO: AFTER WORK,” Chicago Architecture Biennial, November 1, 2023–February 11, 2024.

Jadine Collingwood is an associate curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. She holds a PhD in art history from the University of Chicago, where she completed her dissertation “‘A Tragic Suburban Mentality’: Managerial Lyricism in Contemporary Art.” A curator and art critic, Collingwood researches 20th- and 21st-century art, feminist theory, performance art, sculpture, and new media, among other topics.

Image credit: Courtesy of Zion Estrada and Black Reconstruction Collective

Notes

| [1] | Floating Museum, “Vision,” CAB 5: This is a Rehearsal, Chicago Architecture Biennial. |

| [2] | While the dates of Reconstruction’s start and end are heavily debated, historians roughly align its beginning with Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction and its end with the Compromise of 1877, which withdrew the last federal troops from the South. |

| [3] | Black Reconstruction Collective, “Manifesting Statement,” in Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, ed. Sean Anderson and Mabel O. Wilson (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2021), 168. |