RESTITUTION AND RESONANCES A Roundtable with Memory Biwa and Bénédicte Savoy, moderated by Mahret Ifeoma Kupka and Irene V. Small

Satch Hoyt, „A millisecond to mute the voice that anchors freedom“, (from the / aus „Afro-Sonic Mapping“ project), 2017

Irene V. Small: For the sake of clarity, we have chosen the term restitution as the title for this issue of TEXTE ZUR KUNST to refer to the return of wrongfully acquired and looted objects. But we are all rather ambivalent about its ability to signal the complexity of the issues at stake. Restitution suggests that certain debts or injuries can be concretely repaid or corrected. It doesn’t carry with it the notion of repair or the epistemological shift invited by terms such as rematriation. Bénédicte, in your writing, you talk about the re- in all of these words as pivotal because it compels us to think future and past together. But there’s a whole cluster of terms that have been used to mark various philosophical inflections within the debates about return: repatriation, rematriation, repossession, redress, restoration, reclamation, and homecoming, among them. To start, perhaps you could talk about some of the vocabularies that have been helpful for you – or that you work against – when you engage with these fraught issues.

Bénédicte Savoy: I love this question. This terminological issue is very, very important for two reasons: It is important because all the terminology comes from “our” European languages and is therefore connected to this perspective. Restitution is what the person who has the thing does; they give it back. In this respect, the word already has a perspective in itself, and every use of it carries this perspective with it. That says it all, with just one word. The second reason is that the word restitution remains the absolute key to the whole thing, because it used to be a very polarizing word. I’m talking about the situation five years ago, when nobody in political circles or in museum circles wanted to talk about restitution. At that time, there was a reflex, like a knee-jerk reaction, when the word restitution was used: in politics and even more so in museums, there was a terminological slide toward “circulation.” They didn’t want to talk about restitution; they always wanted to talk about transfer and circulation. The difference is that restitution, with its re-, has temporality in it: there is a before, there is a now, there is an after. The word restitution encapsulates history. Circulation has no history – and that’s why it’s very convenient. For a while, museums said, “Yes, we absolutely have to have more circulation.” But circulating more means talking less about history. A very small footnote to my second point: when we, including Felwine Sarr, made the observation five years ago that in certain circles the word restitution was slipping into the terminology of circulation, we couldn’t explain where this was coming from. Later, when I conducted research on the first restitution debate, I found a document from the 1970s in which museums actively campaigned against restitution. One paragraph in this recommendation is dedicated to terminology: museums decided not to use the word restitution but only ever “transfer.” They said, “We must ban the word; it is too dangerous for us.” [1] After that, I realized why it is so important to use exactly that word.

Memory Biwa: This is such a pertinent question. I usually use the terms return and restitution interchangeably, and mainly to emphasize that these are processes – not events. Integral to them is the anticipation that they lead to ontological and epistemological transformations as well as to forms of reparative justice. Return and restitution should be thought of and enacted within their historical particularities. In this case, I am referring to the Namibian-German context where they are concerned with remembrance processes and their specific modalities and technologies that rehearse continuous relations between living descendants and their ancestors. These connections are evoked by intergenerational aurality and commemoration in central and southern Namibia. Importantly, these processes also have a transnational dimension in the region, because of displacement as a result of colonization, war, and genocide but also through the circulation of ancestral bodies and sacred entities (beings with a vital force) to various institutions in southern Africa and in Europe. Restitution is not just about a one-off event but should be commensurate with the work of repairing catastrophic socioeconomic, political, and ecological consequences of colonization and genocide, which are being experienced by descendants at present. I’ve also been very interested in rephrasing restitution as a repossession. Repossession is to be able to inhabit space and land, and to produce modes of sustainability; this is an expansion of restitution and reparation in its widest context. [2]

BS: Very interesting! I would also like to add a word, because so far I was talking about the situation five years ago. Now, at least in Germany, even museums are talking about restitution, and in France the entire government is doing so. Everyone wants to restitute. It has become a very banal word. My team here at TU Berlin and I have noticed that we are talking more and more about reconnection, about ways of reconnection, about how to reconnect if objects are actually returned. We also really like that it also, in a way, evokes reckon, which is rather difficult to translate from English. On the one hand reconnect, but on the other hand reconnaître in French, which is a bit different than just achieving awareness.

Listening at Pungwe performing as part of / im Rahmen von „Dzimudzangara: A Spectral Figuration of Archival Voices“, Savvy Contemporary, Berlin, 2018

Mahret Ifeoma Kupka: For me, there is a hidden resistance in insisting on terminology. When there was deliberately no talk of restitution, but of circulation, as you describe, Bénédicte, it was all the more important on the part of those fighting for justice to speak of restitution in order to make it clear that something must happen that can be understood as a kind of restoration. Today, European countries restitute: most recently, in December 2022, some German federal states and municipalities officially returned so-called Benin Bronzes held in their public collections to Nigeria. [3] However, we know that restitution can only ever be one part of larger changes, the goal of which must be a different relational ethic between Europe and its former colonies. For me, this battle over terminology is a central part of it. If the terms change, the movement changes accordingly. And that’s exactly what it’s about. Not simply boxing up objects and returning them but being in a constant exchange over them. It is about restitution, reparation, reappropriation, reconnection – a process with many different stages, not necessarily in chronological order.

IS: I want to take up this important point that the issue is not simply returning objects, as if that would finish and complete the process. Memory spoke about land, which is key because when we focus on objects, we forget about the inextricability of land to culture, as well as the ways in which the arbitrary demarcation of nation-states as a result of colonialism continues to impact past and future protocols of restitution. But it’s also important to think in other sensorial registers, such as sound or touch. Memory, I wonder if you could talk a bit about your work with aurality and sonic textures?

MB: There is a significant aural archive and heritage in Namibia, which has relevance for anti-colonial movements and for commemorative processes thereafter. One of the important technologies is oral history, with its attendant modalities passed on between generations. Through oral history, families and communities recall their genealogies, anti-colonial resistance leaders, sacred sites and burial grounds, and migration histories. These are also ways of reclamation. Robert Machiri’s and my work as Listening at Pungwe addresses these dense relational forms of aurality between people, space, and various entities. We also explore how these aural forms are dispersed across embodied commemorative and artistic practices and constitute ways of knowing. These modalities are therefore central to processes of restitution.

Listening at Pungwe, „SunBorn Lullabies and Battle Cries“, 2022, and / und „!Nami‡Nûs (Die Poppe Is Aan Dans)“, 2023

IS: I was listening to one of the works from Listening at Pungwe that, among other elements, combines lullabies and battle cries. It was incredibly moving. Those two affective modalities seem very important in terms of thinking about the complex durationalities of anti-colonial struggle, claims for return, and the responses to them. There are multiple temporalities embedded in these processes.

MB: Thank you, Irene. The audio work is titled SunBorn Lullabies and Battle Cries. Before I speak about it, I want to refer to Uazuvara Katjivena’s book titled Mama Penee: Transcending the Genocide (2020). In the book, elder Katjivena writes about his grandmother, Mama Penee, who at eleven years old witnessed her parents’ execution by German soldiers in central Namibia. When the author was a young boy, his grandmother retold the story to him, and about how she survived the war, fled to Khorixas, and was later found by her family members. In his writing technique, Katjivena used drum rhythm, origin myths, and oral history, connecting different registers of timing and storytelling to illuminate how women narrated and interpreted their life histories in Namibia during colonization and apartheid. These different registers in his storytelling break with the linear structure through which we are told to understand historical experience. So, Robert Machiri and I made the audio work SunBorn Lullabies and Battle Cries, which is set in both Okahandja, central Namibia, and Berlin, Germany. One of the recordings we sampled is a lullaby sung by Lena Fender and recorded in the 1950s in Okahandja. [4] The audio also carries the voices of the Namibian delegation who received despoiled bodies of ancestors and who, at the steps of the Charité university hospital in Berlin, asked their ancestors for protection and guidance during the process of their return to Namibia in 2011. We connected these voices and spaces to sound out the places of contemporary commemoration and restitution in both Namibia and Germany.

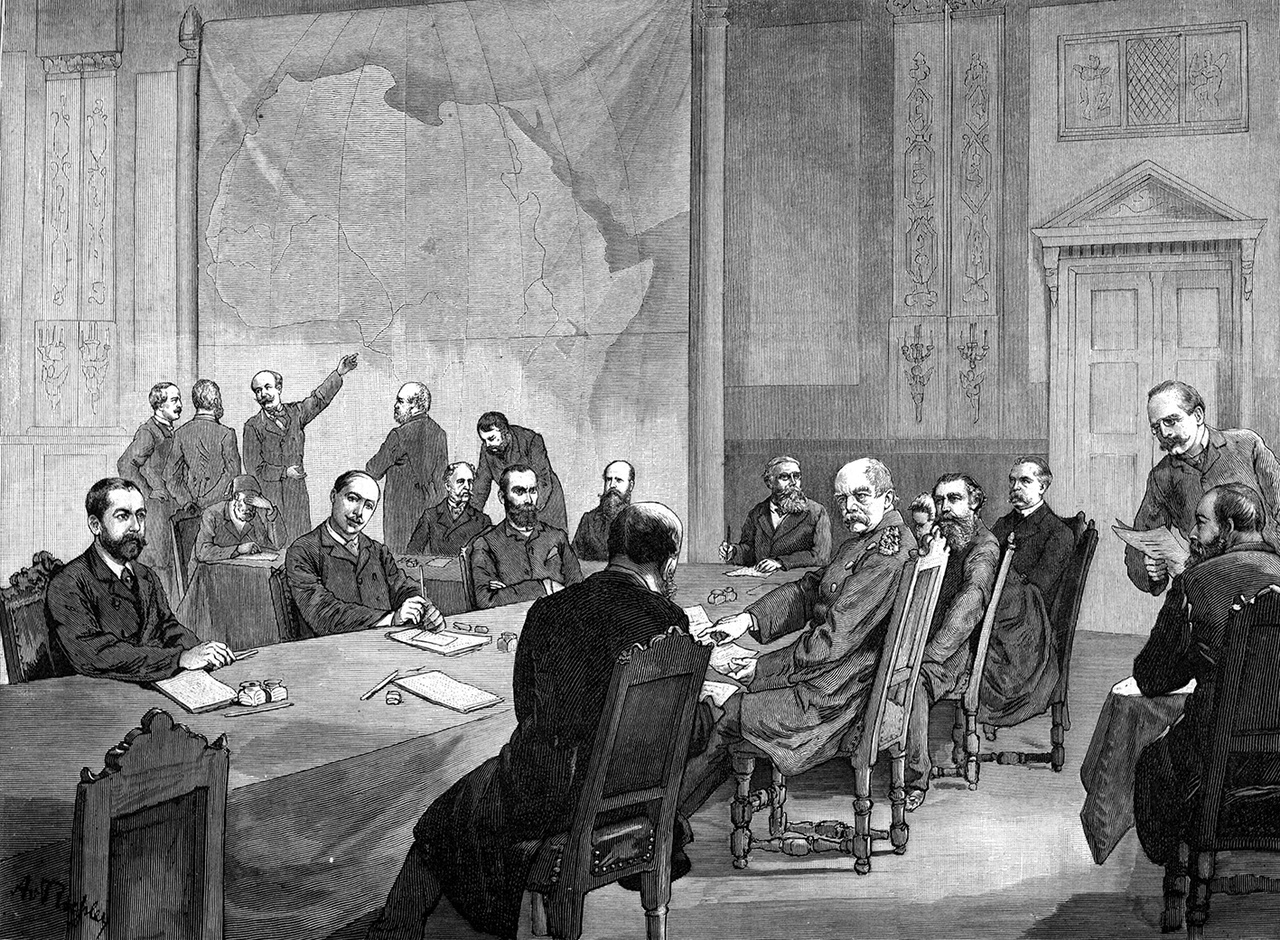

BS: I find what Memory described fascinating. I see the connection between geography and aurality or sound, and the question of the restitution of objects, differently from my Berlin perspective, which is cooler and less associated with memory. What is connected to the question of restitution on a political level is the becoming visible of artificial borders. I remember when we went to Dakar with Felwine Sarr for the first time to work on the report and talked to colleagues; [5] someone said, “Yes, that’s good, restitution will help us abolish Berlin.” I was the only white person and the only Berliner in the room, and I thought, “Ah, what does he mean, abolish Berlin? What does that have to do with restitution?” But I didn’t ask, and only later did I understand what he was trying to say. When things come back – for example, things originally from the Niger River region, where the culture or the objects have been present along the river – it has nothing to do with the fact that they belong to Senegal, to Mali, or to Niger, but that they belong to the whole region. The moment things come back, the states that receive them are empowered to let them circulate. They are empowered to remember that between the source of the Niger River and the mouth, there have been the same objects. This will abolish Berlin – which of course refers to the Berlin Conference or Congo Conference of 1884–85. It seems very important to me that this whole colonial geography is shaken up or at least strongly discussed with the question of restitution. In other words, the “geopolitics of cultural heritage,” as one would say in administrative terms. But also geopoetics – that is, poetics not in the aesthetic sense but in the creative, creating sense of the Greek poiein: restitution changes the poetics of the objects, their agency; it enables them to sing again, if you like. In German, there’s this beautiful word verschollen, used when something or someone has gone missing: objects may be verschollen im Krieg (lost in the war), for instance. I looked into the etymology, and it comes from Schallen, “sound.” The objects no longer sound, or resound. They no longer produce an echo, they are lost. I think the sound comes back with restitution. The people who are connected to the objects are once again able to speak or sing with them, to resonate. The two are connected, as are sound and land. The conversation, the “language of objects” – not in the BMBF sense of a research project [Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research], but the real language of things that actually speak or are spoken to. Everything that Memory just said has a lot to do with our perspective here in the archives or in museum taxonomy; it has to do with museum epistemology, which puts an end to this sounding, this singing of the objects by muting them.

Adalbert von Roessler, Congo Conference / Kongokonferenz, Berlin, 1884

BS: Wow, very cool!

Restitution Study Group and / und USAVIOR, „They Belong to All of Us“, 2022, Filmstill

IS: I have another question that pivots on legal claims to ownership and certain incommensurabilities that arise from colonial histories. The Restitution Study Group, founded by Deadria Farmer-Paellmann in New York, for instance, underscores that the Benin Bronzes, some of which are now being repatriated to the Oba in Benin, as Mahret mentioned, were in fact created within the Benin Kingdom as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. The point is material: the bronze of the manillas, a major currency at the time, she notes, was melted down in order to produce the sculptural works. So, there is a literal relation between these objects and financial value: the financial value of humans-as-commodities, and the current financial value of the objects, which the Restitution Study Group estimates at about $30 billion. The Restitution Study Group contends that any gesture of return or compensation thus needs to be shared or financially redirected to African diasporic communities that trace their roots to this long history of dispossession. [8] Some might argue, however, that this claim depends upon very specific definitions of value (as determined by the market) and ownership. I wonder if there are ways in which these debates allow a reimagination of Western conceptions of property altogether? How do we make sense of claims that at times are incommensurate at an ontological level?

BS: The discussion about restitution to the Oba or the state of Nigeria; the intervention of these colleagues in New York who say “No, this has to be shared,” and so on – for me, that is restitution. Irene, you just suggested that perhaps restitution might change the terms or the denotations of property or ownership, or that we should think about them differently. For me, the notion of restitution changes the notion of cultural heritage. We often assume that cultural heritage is something monolithic, a thing that you give back from A to B and that’s it. Cultural heritage – and the debate about restitution demonstrates this – is also the discussions about it, the way a political community in a country, in a nation, negotiates with the diasporas about the past as it has been passed on through objects. What do we want to do with it, where do we want it, how much of it do we want? In every political community, such discussions only arise when the thing is there. It’s necessary, and it’s a great pleasure when, in the course of the debate about restitution, precisely these controversial discussions erupt, including disputes, because in Europe we are totally used to constantly talking about our cultural heritage, especially in Germany. Why is there no GDR art at all in the museums in Leipzig and Dresden? When will it come? How much of it do we want? All this talk about where we want to have our things, how much of it, who should decide about it – that is cultural heritage. I don’t think I’m in the wrong when I say that in the last 30 years, many African countries have had a lot of discussions about commemoration, history, and coming to terms with the past [Vergangenheitsbewältigung] amongst themselves – but the discussion about one’s relation to material cultural heritage hasn’t taken place because the things weren’t there. The moment there is either the promise that they will come back or, like in the Republic of Benin, where 2.5 tons of material cultural heritage (statutes, thrones, textiles) have now been returned, they really have come back, these discussions start – and that is cultural heritage, that is cultural property. Cultural heritage is also talking about it. It is vital for a community to talk about its cultural material heritage. As long as you can’t do that because the things aren’t there, you miss out on what makes a community what it is. That’s why it’s good that this discussion can take place now. It won’t be a matter of three or four weeks but will accompany a society throughout its life. French society has been talking about le patrimoine since the French Revolution, and talking about it is part of their identity, not just having things. I think every community in the world has the right to argue about it. It’s very lively.

Bismarckstraße 1, Lüderitz, 2017

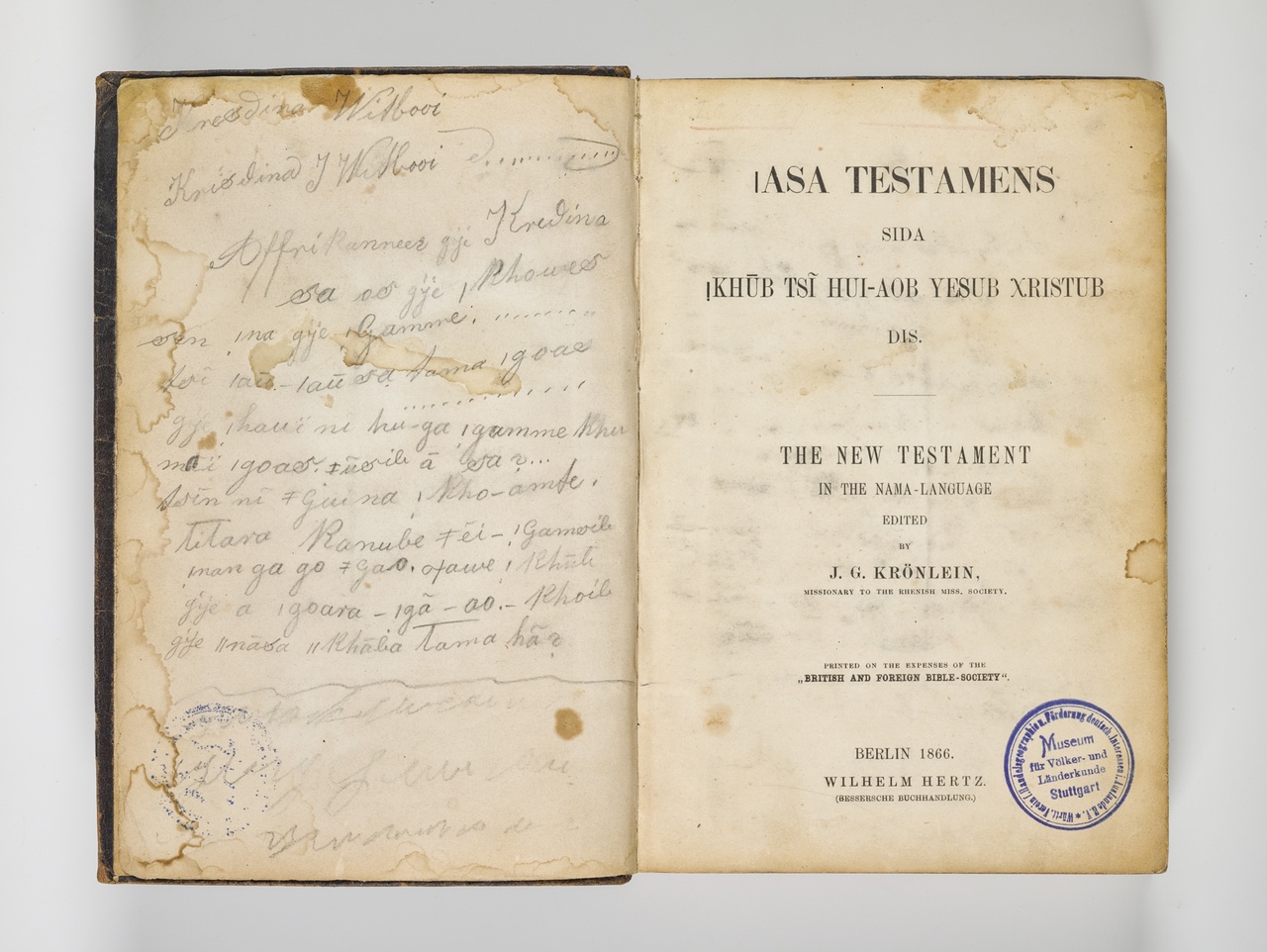

MB: I wonder how we can continue to enliven these conversations and debates. What are the kinds of spaces that we need to create in order for them to continue? In the Namibian case, for example, the Linden Museum’s return of Hendrik Witbooi’s bible and whip in 2019: There are family members still present in Namibia – the great-granddaughters of Hendrik Witbooi for instance – who were expecting that the objects would be returned to them. Then the Namibian state was like, “We’re going to store them in the National Museum and the National Archives,” because these entities are part of national and universal heritage. Which was exactly what European museums were claiming a couple of years ago. That argument was used because Hendrik Witbooi’s papers are part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. There is controversy surrounding the custodianship of the bible and whip, and the government claimed them because Witbooi is a national icon. Like Bénédicte was saying, these are very important conversations to have now. They are about the complex historical processes that relate to forms of dispossession on many fronts – and demands for restitutions are openings where these claims take place. Diasporic claims and debates are valid as restitution encompasses these transnational constellations.

MIK: It is also interesting to see how certain European notions of cultural heritage travel with the objects. When the ownership rights of the Benin Bronzes restituted from Germany were officially transferred by the Nigerian government to the Oba of Benin, whose family has traditionally owned the bronzes, waves of horror swept through German feuilletons. Now they were in private hands, it was said, and all control over them had been lost. Quite a few saw the restitution as a huge mistake, the loss of world cultural heritage. The idea was that the bronzes should be made accessible to the public in the newly founded Edo Museum for West African Art (EMOWAA) in Benin City, a state institution, which has since been renamed MOWAA. Germany invested a lot of money in this new museum. Now the future of the bronzes is uncertain. The Oba’s family wants to build their own museum. Fair enough. This whole process shows that national borders and responsibilities are treated differently in Nigeria as they are in Germany. Transferring cultural heritage appropriated in colonial contexts to a private individual is still unthinkable in Germany. However, the Oba is not a private person in Nigeria but a representative of the Edo people, and the Benin bronzes are part of their culture. Given the country’s history, it should come as no surprise that the rights are being transferred to him.

MB: I think it’s very difficult to reflect on restitution in the context of Namibia and Germany without referring to Germany’s history of denialism. You know, people speak about Germany’s culture of remembrance [Erinnerungskultur]. We speak about Germany’s culture of denialism as it relates to Namibia. The state’s position during the initial stages of the return of human bodies from institutions in Germany back to Namibia attempted to erase historical responsibility for the genocide. It was as if only the scientists and institutions were responsible for what had resulted in heinous acts carried out within institutions, but these were in fact sanctioned by the German state in Namibia and Germany. The demands raised in response to this by traditional leaders and genocide committees organizing at the time actually not only shifted how the processes were to be engaged in, but also resulted in more publicity around restitution and eventually changed museum policies and practices in Namibia and Germany. Restitution as an institutional practice is often framed as separate from the ongoing demands for the German state to recognize historical and contemporary dispossession in Namibia and move toward more holistic and commensurate reparations. As a result, later returns of bodies and cultural entities from museums in Germany were framed outside this context. All of these questions around restitution as institutional practice and what it means in the larger society are wrapped up with Germany’s culture of denialism, and that is why it is important to historicize restitution.

Family bible of Nama leader / Familienbibel des Nama-Anführers Hendrik Witbooi, 1886

MIK: We are having this conversation in early November, and it will only be published in March of next year. I have no idea what kind of world or political situation it will be released into. How do you see the future of the restitution debate? There has been a lot of interest over the last few years, restitutions have been made, and there were at least some attempts to confront Germany’s colonial past and include this in the memory concept. In the context of the latest political developments, how do you see the restitution discourse developing now? Are we experiencing a peak, after which attention will dwindle again, like it did in the 1970s?

MB: Restitution in the context of reparations happens on several fronts: Internally, within our communities, where processes in the aftermath of anti-colonial resistance focused on regenerating communities and where we have seen struggles over land and resources in the past decades – that’s the work that persists, and that we have a shared onus to take up. Restitution in the cultural and artistic arena is an unstoppable movement. Activists, leaders, cultural workers, and institutions both on the African continent and in the diaspora continue to make strides in shifting the discourse and programs on reparations. The demands for restoration will mushroom, as it is linked to all the struggles around the world. However, asymmetrical power relations in terms of research and resources, as well as who the knowledge producers and custodians of the return or restitution processes are, persist as issues. I don’t think this is necessarily just a peak. The culmination of the work around reparations will continue – and influence many other related arenas.

IS: Memory, earlier you mentioned multiple ontologies, and that would seem important to underscore here, too. Rather than thinking within a before-and-after framework for objects upon their return, what are the proliferating models for thinking about institutions, care, and belonging that these objects and their sedimented as well as future histories might offer?

MB: Absolutely. These ontologies should inform modes of restoration possible in the future. Recently, I was listening to an elder councilor describe the meaning of the name of land near !Nami‡Nûs that was declared a restricted area (Sperrgebiet) by the German government because of the diamond mining in the desert along the southern coast of Namibia. The elder described it as the area where the soft shimmering sand blows against your skin (Tsau //Khaeb). [9] That name speaks to the relations between people and land, a sense of an embodied belonging. This belonging is also reflected in the significance of returns, restitution. There is so much that has transpired in the past decades that we can learn from, new organizational configurations between communities, attempts to shift policies, new curriculum and programs between heritage institutions, and between cultural workers from different parts of the world that are demanding restoration also. It was hardly conceivable that this shift would take place at this unprecedented momentum. This is a moment to take note of these gains and move forward.

Warning sign / Warnschild, Tsau //Khaeb National Park, 2018

BS: I share Memory’s assessment; I don’t think we’re dealing with a peak either. My impression is rather that we have found something like a password, a code word, or a shibboleth, a kind of mask in the topic of restitution that allows us to deal with very difficult and violent topics – genocide or mass rape. I have been working on the Cameroon context for three years with Albert Gouaffo and other colleagues at the Université de Dschang, and we have read thousands of pages of officers’ reports, really very brutal things that remind us of today’s massacres very much. With the restitution complex, we have collectively devised a method with which we talk about art, museums, poetry, sound, ancestors, memory – which all sounds soft. But in this way, we indirectly address brutal topics, too: land, death, genocide, encroachment, extractivism. The debate around restitution has expanded. It now encompasses a collective need to talk about historical injustice, colonization, reparation, and, perhaps, about current injustice as well. It looks like the detour via restitution is being taken more often, because restitution – also repair or care – gives us all the gentleness that we collectively need as hope. At some point, it will no longer be about museums and projects but about ways of reencountering, or a new relational ethics that we need with each other as humanity. I’m increasingly seeing the term restitution – to close the terminological loop – used to talk about much more difficult things. We are having exchanges about objects and museums, but we often mean something more and different. Some have found in this a possibility to discuss current atrocities without naming them too explicitly.

MIK: This brings us full circle: at the beginning, we talked about terminology, about our understanding of restitution, now we are looking toward the future, to a time that seems more uncertain and divided than ever. We lack the language for so many issues and the necessary room to articulate them. I absolutely agree with you, Bénédicte, that with our understanding of restitution, we are able to create spaces to talk about things that still weigh too heavily to be discussed in adequate terms elsewhere.

IS: Both you, Bénédicte, in your historical work, and Memory, in what you say just now, demonstrate that resistance always exceeds attempts to shut it down. Resistance always finds lines of flight and mechanisms for legibility (or camouflage, when that is needed). It’s always there. So we need to continue to find ways of expressing how history repeats, bleeds into, and is displaced within the present. We need to continue to look and listen for these reverberations. I’m so grateful to you all for sharing this space of discussion and returning us to the urgency of the now.

Memory Biwa is a historian and artist. Her work on commemorative and reparative processes in Namibia encompasses a wider discourse and practice on restitution and reparations. Biwa’s focus on aurality and performance informs notions of subjectivity and the recentering of alternate epistemologies as well as imaginaries. Biwa cocurated “Die Vibration der Dinge” (Triennale Kleinplastik Fellbach, 2022), “P(r)ossession Pedagogies” (Namibia artist residency program at Akademie Schloss Solitude, 2023), and “A Sacred Story at the Tree of Life” (IFA Gallery Berlin, 2023). Biwa is part of the duo Listening at Pungwe with Robert Machiri.

Bénédicte Savoy is a professor for modern art history at Technische Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on museum history, French-German cultural transfer, Nazi-looted art, and postcolonial provenance research. In 2018, together with the Senegalese scholar Felwine Sarr, she wrote the report The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics, commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron. She holds numerous awards and memberships at a range of academic institutions, advisory boards, and committees. Her most recent publications include the book Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat (Princeton University Press, 2022) and the jointly written open-access publication Atlas der Abwesenheit. Kameruns Kulturerbe in Deutschland (Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 2023).

Mahret Ifeoma Kupka is an art historian, curator, and independent author. In her exhibitions, lectures, writings, and interdisciplinary projects, she deals with the topics of racism, culture of remembrance (Erinnerungskultur), representation, and the decolonization of art and cultural practice in Europe and on the African continent.

Irene V. Small is an associate professor of contemporary art and criticism in the Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, where she is a member of the Executive Committee for the Program in Media and Modernity and an affiliate of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Program in Latin American Studies. She is the author of Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (University of Chicago Press, 2016) and has published on topics ranging from the legacy of the avant-garde to radical pedagogy, social sculpture, decolonial practices, and the afterlives of slavery. Her second book, The Organic Line: Toward a Topology of Modernism, is forthcoming from Zone Books in 2024.

Image credit: 1. © Satch Hoyt; 2. Photo Ola Zielińska; 3. Courtesy of Listening at Pungwe (Memory Biwa, Robert Machiri); 4. Public domain / Adalbert von Rößler; 5. Courtesy of Deadria Farmer-Paellmann; 6. Public domain; 7. © Linden-Museum Stuttgart, photo Dominik Drasdow; 8. Photo Hanspeter Baumeler

Notes

| [1] | For more, see Bénédicte Savoy, Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat, trans. Susanne Meyer-Abich (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022). |

| [2] | For more, see Memory Biwa, “Afterlives of Genocide: Return of Human Bodies from Berlin to Windhoek, 2011,” in Memory and Genocide: On What Remains and the Possibility of Representation, ed. Fazil Moradi, Ralph Buchenhorst, and Maria Six-Hohenbalken (London: Routledge, 2017). |

| [3] | Editor’s note: The holders of the respective collections, which in Germany are the federal states and municipalities, decide on transfers of ownership. The responsible Bavarian ministry currently states: “To date, no decision has been made by the Ministry of Art regarding the transfer of ownership of Benin objects from the Museum Fünf Kontinente.” (Dec. 1, 2023) |

| [4] | In the recording, you hear the voices of elders Lena Fender and Fritz //Hamaseb in Okahandja, central Namibia, 1954 (from the Ernst and Ruth Dammann Sound Collection, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel), as well as Jarimbovandu Alex Kaputu with Ovaherero and Nama delegates – including members of the Genocide Committees – at the Charité hospital, Berlin (original recording by Larissa Förster at the Charité, September 2011, https://soundcloud.com/europeannomadicbiennial/sunborn-lullabies-and-battle-cries-by-memory-biwa). |

| [5] | Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics, trans. Drew S. Burk (Paris: Ministère de la Culture, November 2018). |

| [6] | Research was conducted in the framework of the REPATRIATES project. Thanks to Julia Binter and Johanna Ndahekelekwa Nghishiko, who are part of the Confronting Colonial Pasts, Envisioning Creative Futures project between the museums in Berlin and Namibia, and to Robert Machiri and Gabriel Rossell-Santillán, who were the coproducers of parts of the research process in Berlin during and after the returns. |

| [7] | Provenance research was conducted by Werner Hillebrecht, working in collaboration with the Confronting Colonial Pasts, Envisioning Creative Futures project of the Museums Association of Namibia and Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin. |

| [8] | For information about the Restitution Study Group, see their website https://rsgincorp.org/. |

| [9] | !Aman councilor Cornelius Fredericks spoke about Tsau //Khaeb at a workshop held by the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) in Berlin, in December 2023, as part of the Inherited Testimonies project. The project, about historical sites of German occupation and genocide in Namibia, is a partnership between Forensic Architecture, Forensis, Nama Traditional Leaders Association, Ovaherero Traditional Authority, and ECCHR. |