ON DIAMOND STINGILY’S “ENTRYWAYS”

“Diamond Stingily: Wall Sits,” Kunstverein München, 2019

In her investigation of Diamond Stingily’s sculptural practice, Paulina Pobocha reaches back some 100 years to the readymades of Marcel Duchamp. Pobocha utilizes comparison – the classic model of art historical epistemology par excellence – in a precise and personal prose that is as simultaneously amusing and serious as its subject. Engaging with the series “Entryways” in this way underscores the autonomy of Stingily’s door installations. Pobocha views them as hinging exclusively on their materiality, arguing that biographical accompaniments can safely be set aside.

More than one 100 years have passed since Marcel Duchamp purchased a urinal from J. L. Mott Iron Works in New York, turned it on its back, signed and dated it “R. Mutt 1917,” and then submitted it, with the title Fountain, to that year’s Society of Independent Artists exhibition. This brazen (and funny) gesture begat the readymade and forever changed what counts as art and what doesn’t. It turns out that everything that claims to be does. Whether it’s interesting or important or good or bad or even, despite all claims, art at all, and who decides, is another question altogether. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Among its many jobs, the readymade liberated art from a manual form of representation, be it through painting, or sculpture, or writing, even. Why picture a thing that already exists in the world when you can just use that very thing and thus cut out the go-between, otherwise known as the artist’s hand? There are many reasons, and they persist. And so, too, does the readymade in its myriad of incarnations: the assisted readymade, the found object, assemblage, and other designations that, while adjacent to one another, are not exactly interchangeable.

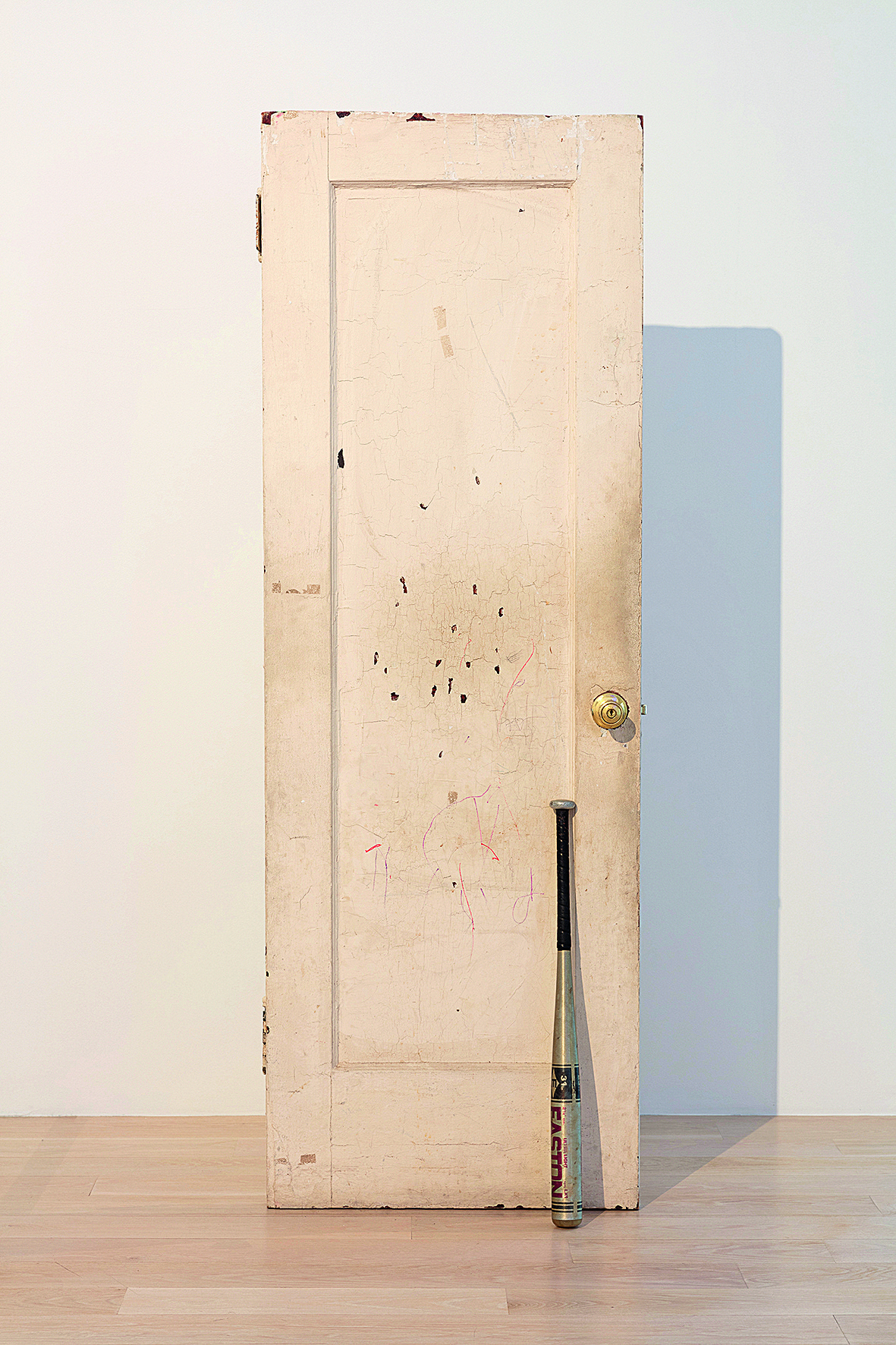

Diamond Stingily takes things that exist in the world and uses them in her sculptures and sculptural installations. These are two of several mediums within which she works. Her best-known series of sculptures, made between 2016 and 2021, is titled Entryways. Approximately 25 individual works comprise the group. While other objects occasionally enter the scenario, each Entryway is made of three critical components: a door, a baseball bat, and a metal pole.

The doors are domestic. These are not doors that would lead to the interiors of industrial buildings or retail stores, restaurants, offices, and other kinds of public or semipublic spaces. If they were to lead anywhere, they would lead from the house to the street. These are not doors to closets or bedrooms, or pocket doors to the parlor; they don’t divide the home. The locks – sometimes dead bolts, sometimes door chains – give that away. They are called Entryways, but their orientation vis-à-vis the viewer suggests movement from inside to outside – exitways, perhaps, but that depends on who’s speaking.

Diamond Stingily, “Entryways,” 2021

Entryways are made using doors common to North America.

None of the doors is new. They are distressed, dirty, banged up. These patinas hold memories. They exude narrative. The Entryways have seen things you people wouldn’t believe – moments now lost in time, like tears in rain.

A baseball bat leans against each door.

Already that is a lot of information. A picture is worth a thousand words.

Akin to mounting hardware, on the verso of every door, a pipe connects it to the wall behind and holds it in its vertical position. The distance between the door and the wall is dependent on the length of the pipe and varies from work to work. The doors are never installed flush against the wall, avoiding even the suggestion that they may lead somewhere. Fixed in place, they are things unto themselves; they don’t open, and they don’t close; they lead to nowhere.

While many of Stingily’s sculptures are constructed from everyday objects, Duchamp never enters the conversation around her work. For good reason. First of all, 100 years separates Fountain from works such as the Entryways, and that period has been occupied by countless examples of art that engages readymades in some form. Singling Stingily out from this group may seem arbitrary, and perhaps it is. Second of all, Duchamp’s Fountain and the readymades that follow are self-reflexive (at least initially; things get dicey when the replicas enter the world). They point to their status as art objects. That’s not very far at all. A consideration of the ontology of the readymade is at least a part of what makes a readymade a readymade. It’s also what made the readymade, in 1917, a radical proposition. Stingily’s sculptures made from doors and baseball bats don’t share these concerns; they inhabit a different genre of gesture. Yet one way to best understand and define the ways in which Stingily uses objects that could be called readymades is by demonstrating why and how they aren’t, and what they then are.

Entryways are rooted in personal history. The works quote her grandmother’s practice of keeping a baseball bat near the entrance to her home for protection, should she need it. The story is so central to the discussion around Entryways that it’s almost a part of the work.

Is sculpture so deficient that it must derive significance from biography?

In Artforum, Jacob Proctor, reviewing a 2019 solo exhibition of Stingily’s, writes,

At a moment when the art world is awash in work about identity, one thing that distinguishes Stingily is the degree to which her recourse to personal history opens her work up to broader audiences. For the viewers of this exhibition […] it matters that her grandmother kept a bat by the front door. [1]

“Diamond Stingily: Elephant Memory,” Ramiken Crucible, New York, 2016

This story is so central to the discussion around “Entryways” that it’s almost a part of the work.*

But it’s not.

Sculpture articulates three-dimensional space. That space can be occupied by matter, or not – empty space can also be sculptural.

Stingily, an accomplished writer, could have described the memory of her grandmother keeping a bat near the front door of her home in an essay. Maybe she has. She’s shared the story, with varying degrees of specificity, in many interviews. She also turned that memory into a sculpture. She didn’t have to.

Each Entryway is made of three critical components: the door, the baseball bat, and the metal pole. Viewers encountering these sculptures must confront their physicality, which includes not only what they are but also the things from which they are made, how those things relate to one another, how they function in the overall composition, the space the sculptures assume, the space they don’t, how they are positioned, how their bodies relate to ours: Must we approach them head-on or from the side? Is it possible to circumnavigate the sculpture and experience it in the round? These questions are paramount to an understanding of the Entryways. Their many material incidents give way to a richness of readings. They tell us all we need to know. Everything else is just icing on the cake. And the cake is plenty good.

Diamond Stingily, “Entryways,” 2017

When I come upon Duchamp’s readymades in a museum, now 100 years after he introduced them to the world, I find them very disruptive, not least because they make me laugh. We’ve seen all these objects before, and it’s this banality that makes them stranger than strange. Consider In Advance of the Broken Arm (1964, after lost original), a work he first made (or, more accurately, purchased from a hardware store) in 1915, two years before the urinal became a sculpture. It’s a snow shovel hanging on display from the ceiling. Its title, painted onto the work, playfully forecasts what might happen if this object doesn’t perform its intended function. That’s it. Of all the things available for purchase in a hardware store, why a snow shovel? Why not.

What Duchamp called “assisted readymades” are altogether different, except that they, too, are stranger than strange. An “assisted readymade” is a sculpture that combines at least two incommensurate things. The most well-known example is also the earliest sculpture he made using mass-produced goods: Bicycle Wheel (1951, after lost original of 1913). Duchamp took a bicycle wheel, turned it upside down, and attached it to a wooden stool; in this configuration, the wheel could still spin. While both the bicycle wheel and the stool are commonplace enough – and certainly were in 1913 – in combination, they are utterly bewildering. This simple gesture of attaching one thing to another brought forth an object bereft of purpose, whose form was not only entirely new but also previously unfathomable despite its simplicity.

An understanding of Stingily’s sculptures is wholly other, in ways of supreme significance. While she doesn’t address race directly, we can surmise from Stingily’s oeuvre that the experiences from which she draws are particularly common to Black communities. Leaving the work open-ended makes it all the more capacious.

A baseball bat leaning against a battered door is familiar whether from life, from film, from photography, or from elsewhere in popular culture, at least in the United States. The conjunction is known, and it makes sense. With extreme economy, Stingily cannily addresses the oppressive threat of violence that imperils daily life and promises to breach the threshold of the home. That the doors are old – some with their paint chipping, some stained by the hands that touched them again and again, some hastily patched with scraps of wood – suggests that they belonged to people who could afford to live in a house but could not afford to repair or replace the barrier separating themselves from the world beyond. The precarity of this circumstance is concentrated in the baseball bat that leans, almost nonchalantly, against the door, as if to suggest that this condition is so constant as to be commonplace. No need to ring the alarm.

These sculptures are far from deficient. Their materiality tells us everything we need to know. The Entryways hold stories – maybe they’re Stingily’s, maybe her grandmother’s, maybe yours, maybe ours.

Paulina Pobocha is a writer and a senior curator at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Image credit: 1. + 2. Courtesy the artist, Queer Thoughts, New York, and Greene Naftali, New York; 3. Courtesy of Diamond Stingily and Ramiken Crucible, photo Dario Lasagni; 4. Courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, photo Fredrik Nilsen

Note

| [1] | Jacob Proctor, “Diamond Stingily: Kunstverein München,” Artforum 58, no. 4 (December 2019): 239. |