Digital Reflex Avery Singer and Ed Atkins respond to Texte zur Kunst

One reason for the recent surge in work that re-examines the status of images, their distribution, techniques and effects, seems to lie in the artistic appropriation of digital technologies for the creation and modification of pictures. These enable new modes of shaping the image, in digital media, but also in relation to more traditional media that are now reconfigured by way of the digital, ranging from film to the most classical medium: painting. New potentialities emerge: for example the transformation of the concepts of filmic or painterly figuration and image composition, both of which can now be executed on the basis of algorithms and design programs.

We have asked artists Avery Singer and Ed Atkins how, in their respective work, they confront and appropriate these technologies for creating images. How do they allow artists to reconfigure their image-work, especially in relation to traditional modes of generating pictures? And, on a more general level, how do the artists relate their concepts and practices of the image to their concepts and practices of art?

AVERY SINGER

Vision and Historicization

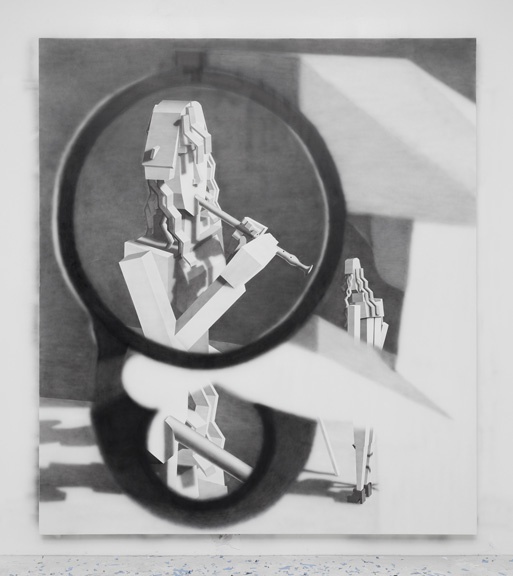

Avery Singer, „Director“, 2014

Avery Singer, „Director“, 2014

Art provides us with an awareness of our own dignity and limitations. As an artist, I often find myself speculating about the meanings imparted on images via their mass consumption, and how that condition relates to the ways in which changes in technology are disseminated and circulated among individuals. Technology has a peculiar relationship to society as a productive force in that it is a part of the change that occurs within it – such that technology is both enforced by people’s desires and yet produces new desires for these same individuals. Capitalists produce the consumer’s wants, to ensure the consumption of their products and thus the valorization of their capital. This has been proven over history.

Perception is a narrative fiction. An image, though, is more than what the creative forces of the media enable us to experience, as it enters our awareness first through our own various means of acuity. I privilege perspicacity, subjectivity, and vision in my work as much as I do the promulgation of imagery through mass-media sources and the Internet. This duality is a way I feel that I personally can tackle issues of subjecthood in my chosen medium of painting. Painting has that quality of constantly planting a philosophical investigation into its own status, prompting a continual investigation into what it means to be a subject, to occupy the mythical, scenic, grand position of the subject. It’s a space where existential choices can be questioned in the postmodern scene, or to shed light on the project of being at revolution with society and one’s own existence. Painting is a site onto which we (artists and viewers alike) project and interpret the abstract nature of our own thoughts and experiences within the framework of a cultural outlet.

Meme erstellt von / by Avery Singer

Meme erstellt von / by Avery Singer

The Buzzfeeds, the Instagram accounts, the blogs, and any other number of web outlets supply our coffeehouse attitudes these days. Nonconformists share their liberal banter via these sources, and ultimately affirm them through public postings on social media outlets. Facebook and Instagram are the café. And we are still modernists within this space, engaging in the project of giving expression to the feelings reality elicits in us. We take the things we see in nature, and reflect upon them, the site of which has now expanded to include virtual reality space. Our culture’s secularization has brought with it a suspicion of the meaning of society. We enter adulthood believing that life can now become our own construction. So a meme with Beyonce asking the viewer a question that mocks her own agency is a mirror to our questioning of ourselves within a potentially meaningless society. The hilarious and imploring meme of a compromised celebrity figure is really just an expression of the suspicion of power.

Our eyes are like cameras, behind which we find the self. One of the most important questions I’ve been asked by a teacher was simply, “Don’t you feel like you’re behind your own eyes?” This query instantly raised what could potentially be a lifetime of crises for me. The obvious answer, once you’ve considered it, is “Yes, I feel like I’m behind my eyes.” I recently tried to translate this bizarre and stupefying realization into painting. The work depicts the experience of bringing something so close to one’s eyes that both the hand and the object it grasps go out of focus, becoming indistinguishable and overbearing. The hand in this painting clutches a monocular, rendering the latter as both a tool of abstraction and elucidation, bringing to view a new image, one full of clarity and detail, while being enshrouded in a visual fog. The distanced scenario around the blurry picture frame is intended as a third order in the image a relationship to which the viewer forms.

Let’s utilize metaphor again, to look at artistic processes with a self-deprecating twist (I like comparing artistic activity to embarrassing and off-color things). One’s practice could be said to be like a vomitorium, where everyone has dined on images, experiences, and varying degrees of scholarship (a three-course meal). You have to know when your gut contains exactly the right mixture of ingredients to make you want to stick your finger down your throat – because you don’t want to have to go through all that retching for nought. Forgive this implied comparison if you find it distasteful (pun intended).

Meme erstellt von / by Avery Singer

Meme erstellt von / by Avery Singer

Language is the ultimate arbiter in evincing meaning. That last paragraph was a jab at the elasticity of language. Many great wars have been waged over the misinterpretation of texts (whether they be of the leather-bound or the mobile phone variety). We also have that saying that a picture can speak a thousand words. For me, the power in art is that it collapses the nature of experience and the intellectual understanding of it into one gesture. Great art leaves us wordless, unable to describe the meaning or experience it imparts, because it has been so successfully done for us. It simply exists in us for the time that we are able to experience it, and it lives with us permanently as memory.

When I began painting, I felt pretty strongly that one is going to have a really difficult time using graphic design tools to create relevant imagery. It’s been exhausted. It’s used up, unless you started at it almost a decade or two ago. So, I approached 3D modeling freeware as a way to further the project of evoking digital space in painting, or creating new possibilities for portraying naturalism. To make the computer the site where initial sketching and idea-hatching occurs, and then bringing it back into the material world of object-making through a process-heavy approach that appears midway between printing, photography, and painting. It was important for me that the work be black-and-white, to confuse the materiality and thus the relationship of the viewer to their own accustomed viewing habits.

When I was at Skowhegan last summer, I listened to an audio recording of a lecture Ad Reinhardt gave there a few decades ago. At the finale of his talk, he took his audience to task (something I wish would happen more often) for daring not to emulate what had recently been on display at group exhibitions in and around New York City. I feel the same way in regard to painting trends. What I want to make clear to others is: If we plan to continue representing our digitally based experiences in painting, then aestheticized graphic design is to be disposed of as a way to translate the nature of these experiences, for it will only present an antiquated and unfinished view of our world. Would we allow ourselves to occupy such a retrogressive position as readily in any other medium? (Potentially, yes. Bad question?) However, as such, I believe it’s time to look to new paths for examining images and metaphors for representation.

ED ATKINS

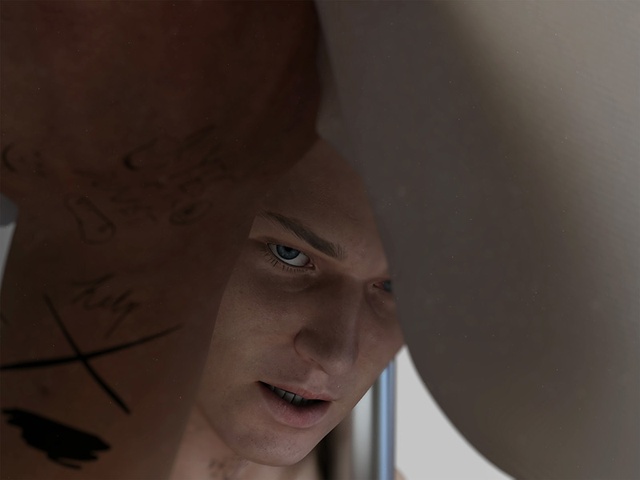

Ed Atkins, „Ribbons“, 2014, Filmstill / film still

Ed Atkins, „Ribbons“, 2014, Filmstill / film still

As someone whose thinking has always tended toward the literary, the appeal of making work entirely on computers relates conspicuously to ideas of literality and figuration. In a few important ways, the things I make are conjured from and reside and remain within a figurative location. Seldom do the things I make materialize outside of their digital mode; rather, they remain fundamentally vague, unresolved – even and especially as they pertain to precise verisimilitude, explicitness or corporeal effectivity. In a computer-generated universe, metaphor is as if rendered literal – metaphors seem to come true, in a way – albeit girded by the increasingly indiscernible digital firmament of figuration. The “seeming” of literality belies, weirdly, its absence. In practice it feels like you get to have things both ways: virtuosic hyperrealism you can undo and redo with abandon. The apparent liberty of having no proper recourse to reality (appropriation now being something akin to remembering things, for example) has meant that I’ve felt more able to manipulate images, sounds, and words. And this power has felt increasingly permissible. If a human figure is computer-generated, I feel able to treat it with impunity, if only because it can’t really exist outside the fantasy of code. Consequence is held in abeyance. Because it was generated – because it came from nothing – it doesn’t really cite life, at least not in a pragmatic way. I suppose this is precisely what I engage with in my work. Avatars are surrogates by another name, realistic stand-ins whose material ambiguity, obscure providence, and true-to-life appearance makes them ideal understudies of power, violence, and sexuality. It is that characteristic of representational fidelity that is of most importance, I often think, as it does the job of shifting the image to a point of creative intangibility where the object is sourceless, unauthored, and certainly not revenant or haunted, as nostalgia is so often analogized. CGI was never “alive”. Ghosts and zombies and vampires no longer provide resemblance, tradition. The computer-generated image feels almost entirely withdrawn from its subject, production, and relatable feasibility.

Previously, I was more than a little ambivalent about filming people, ethically and structurally speaking. What I wanted to do to the footage – the kind of medium-reflexive editing I wanted to push – felt exploitative of its subject. If I wanted to summon tangible and affective responses (which I did and still do), I had to believe in a causal relationship between symbolic and real-world violence. Cutting up a face, however figurative (or skeuomorphic: the razor-blade cutting tool in Adobe Premiere, et cetera), alludes to well cutting up a face. And not just any face, but the real-world person’s face I videoed or appropriated for the express purpose. With computer generation, this image’s explicitness is switched, so that the artifice of the figure, the face for example, is obviated by its lack of relation to any kind of material authenticity at any stage of its subsistence. This kind of withdrawal seems reminiscent of those more or less real distances in digitally defined relations, whether that be between consumers, workers, lovers, or concepts. More often than not, when we speak of the “immaterial”, we’re really talking about matter deferred – matter that is not imminent. The digital isn’t a lack: Every “cloud” has a rusting, heaving, scorched lining; every black mirror of an iPhone carefully omits the indexing of a thousand traumatized lives over there, out of sight, in its occult, vanished material history. The lexicon of digital terminology, and the inscrutable, hermetic hardware, are tropes to remystify; They are ideologically rigged modes of figuration. Likewise, to speak of things as literally immaterial affords a convenient understanding of the digital as basically magic – as a kind of sophisticated, contemporary theism divested of guilt. Rapaciousness continues apace.

Ed Atkins, „Ribbons“, 2014, Filmstill / film still

Ed Atkins, „Ribbons“, 2014, Filmstill / film still

So my approach to CGI is in one way a kind of sophistry: I indulge the fiction of CGI’s peculiar mythology in order to differentiate it according to criteria other than my sentiment – how it makes me feel, which is what it most clearly provokes. I protest too much, I suspect. The impunity I feel CGI affords is, I have no doubt, reliant on yet another thick block of my prevailing ignorance and my fantasy in the face of that ignorance. Which isn’t to say that seeking sufficient surrogacy isn’t a worthy endeavor. And when I say “sufficient”, I mean something that can suffer without suffering, perform without performance, and be without being. The tacit promise is one of paradox, which, I would think, is only sustainable through fantasy, metaphor, irresolution – all of which are the hallmarks of figured digitality. The comparison I’ve rehearsed for several years now is that of my videos to cadavers; that, really, I wanted to make cadavers. Literally, dead men. The kind of images I want would ideally constitute what a cadaver could be, if only nothing had to die in order for it to come into being. Which is, I would suggest, what one might ultimately want of an image, really.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter so much whether a computer-generated image is or isn’t fundamentally material in its constitution, but more that it’s really very hard to work out what a given image is picturing. Hence the estranging effects – that rebuttal that seems so redolent of squatting in front of a mirror. There’s an idea of CGI’s potential to manifest desire – of CGI as mainlined images of desire, molded and conjured from algorithmic thin air, with a verisimilitude that’s at once hysterical, abject, and gratuitous. That these qualities are both excessive and discarnate can, I think, serve as a condition of embodiment for us – returning us, changed, to ourselves.