Bohemia = Utopia?

Starting with his pop-nihilist classic “Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture” (1991), writer and visual artist Douglas Coupland has been giving us language to describe our near futures since well pre-Y2K.

In the essay that follows, the Canadian author uses the hyperlinked lens of our almost-present to filter the slacker bohemia of our younger selves.

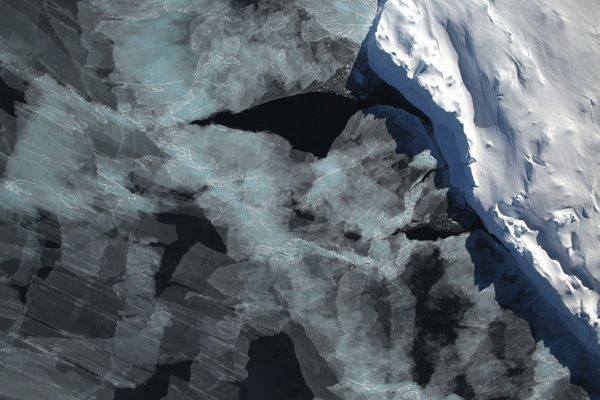

Whenever I bring up the subject of bohemianism, the collective reaction is so uniformly: “What do you mean by bohemian! Define your terms! Forget it, I don’t even want to discuss this!” that it tells me that I seem to have pushed a button. But we all already know what bohemianism means. And so it makes me wonder what it is about its common definition that we dislike so much – this freedom to live outside the mainstream, eking out a living preferably doing something creative, an existence lacking roots but affording the freedom to travel and live with other bohemians. Doesn’t this basically describe most self-employed people in the art world – all those kept afloat by occasional sales, grants, residencies, discount flights to and from Berlin, London, and NYC, the odd teaching gig, as well as by their partners’ or family’s income? The button I think I’ve pushed is the collective realization that the middle class, like an Antarctic ice shelf, is vanishing at a shocking rate and will, within 15 to 20 years, most likely be gone. In its stead we will have, it seems, a new class structure – one that will alter the notion of what bohemian freedom is, while simultaneously reducing its possibility.

A fully connected world no longer needs a middle class.

This scenario was easy enough to predict back in the late 1980s. What’s been more difficult to handle has been watching the middle class disintegrate in real time. But since few are in denial about the middle class’s impending doom, the magic thing about the present moment is that everyone everywhere is, with great anxiety, trying to figure out what comes next. What comes next I would call the “blank-collar class.” It’s not Fordist blue-collar. It’s not “Hi! It’s 1978 and I’m a travel agent!” white-collar. Blank collar means this – and listen carefully because this is the rest of your life – if you don’t possess an actual skill (surgery, baking, plumbing) then prepare to cobble together a financial living doing a mishmash of random semi-skilled things: massaging, lawn-mowing, and babysitting the children of people who actually do possess skills, or who own the means of production, or the copper mine, or who are beautiful and charismatic. And here’s the clincher: The only thing that is going to make any of this tolerable is that you have uninterrupted high-quality access to smoking hot Wi-Fi. Almost any state of being is okay in the twenty-first century as long as you can remain connected to this thing that turns you into something that is more than merely human.

Use jets while you still can.

In the 1990s, people dropping out of the mainstream were demonized for refusing to engage with capitalism: “They won’t get real jobs! Who do they think they are!” Such castigation now seems quaint; now that we’re no longer really sure what capitalism is any more. Film director Richard Linklater said of slackerism, “Withdrawal in disgust is not the same as apathy.” And he was right. If we have nostalgia for the early 1990s, it’s because we have nostalgia for a time when opting out of mainstream culture in disgust was push-button simple and economically not too difficult. Slackerism – bohemianism – means having an ideal for which taking a hit comfort-wise is worth the price. Bohemianism means not wanting a day job. Bohemianism means more sex with cooler partners. Bohemianism means Chianti bottles covered in dripped wax. Bohemianism means syphilis and having to borrow money from an employed sibling. Bohemianism means an early death from tuberculosis. Bohemianism is riddled with clichés. To the mainstream, bohemia is utopia, a freedom from structure and a place where there is little difference between our inner and outer selves, a world of perpetual Halloween. Bohemia is a part of town you can visit in the spirit of slumming to pick up on fashion trends, eat iffy food, drink cheap booze, and then leave, like a theme park ride called “Classlessness.” Classlessness has always been a state linked to bohemianism, and one that was soon idealized. In the US, it was a broad ideal for almost two centuries, England for about eleven and a half years; the former Eastern Bloc had pseudo-classlessness but then lately things there and everywhere else started going all one-percenty.

From the inside, bohemians know they’re on the inside and it’s amusing to watch the slummers come and go. But then maybe you’re in bohemia because life simply dumped you there; bohemia isn’t always elective. Maybe your school grades weren’t good enough to take you elsewhere. Maybe you have bad social skills. Maybe you drink too much. Maybe you hate your family or vice versa. Maybe you like making experimental videos but it really doesn’t pay the bills. But probably everyone you hang with is a mixture of all of this and of people who genuinely see creativity as their vocation and could “never fit into the real world.”

The real world. Ahhh … that’s the new twist.

The thing is, the real world from which people want to escape is changing so quickly, we’re no longer sure of what it is we’d be escaping from were we to turn bohemian. Meanwhile, the safe haven called Bohemia is shrinking and morphing at the same time. There are a dwindling number of escape holes. In the building where you work, that couple living down the hall moved out. They now sell their knitwear on Etsy and live on Long Island where they found affordable rent. The crazy guy downstairs who used to do big Color Field canvases started taking Effexor and now does website design for Schering-Plough. The kids with the pop-up gallery? They’re millennials. They have trouble making decisions on their own. They casually blend the real world and the Internet world together and see little difference between the two. They live online. They have blogs read by 277 unique visitors every month for an average read time of six minutes and four seconds.

Douglas Coupland, “Always One Step Ahead of You Euroboy”, 2014

Douglas Coupland, “Always One Step Ahead of You Euroboy”, 2014

Millennials pick a city, San Francisco, say, and visit the website of every single gallery there, and then meticulously and voraciously click through every JPEG of every artist’s work, saving JPEGS of their favorites, and then they burn through another city’s galleries and they amass a stunning knowledge of who’s doing what where, and then, knowing this, they try to find their own graphic take on abstraction or performance or installation and establish a small branding niche for themselves making JPEGS to be consumed by millennials just like themselves. It’s a thing. Those millennials who ran the pop-up gallery have actually split up; one does freelance character design now for a Korean avatar creation mill; one has a two-day-a-week job as an assistant arts administrator at a local museum whose budget is going to be halved in next month’s plebiscite; one now spends most of her time gaming online and gets handouts from her sister the dentist. If anything, the lives of these millennials are starting to resemble the lives of Japan’s hikikomori, children who grow up, leave home, and then return home very quickly, going back to their old bedrooms, which they never leave. Ever. There are about 750,000 hikikomori in Japan, and they are a massive and fascinating problem. In Tokyo, if the police get a call about domestic violence, it’s not like in the US, where you assume it’s husband versus wife. In Japan, the police assume it’s a hikikomori abusing a parent. A 1992 slacker living in a basement suite and working at a local record store seems a billion miles away from what societal exclusion is, with staggering speed, now becoming.

And it’s getting harder to glamorize exclusion, to romanticize the periphery, to idealize a “bohemian” way of life that is often simply the resulting end state of genetics, brain pathologies, obsolesced skills, unharmonized immigration regulations, failed social safety nets, an art market that isn’t really sure what it is any more (Paddle 8!), as well as art-world theories that seem like alchemical lead-into-gold twaddle in the face of the Internet’s relentless tsunami of flatness and reclassification and endless unspoken taunts to all of us to the effect of: Just what does it mean to be human? Why are we even here? Camus said we’re the only animal that doesn’t know how to be itself. As the Internet develops, we’re seeing, in fast forward, countless new ways that we become less clear on who or what we are, and why we’re here. Does the Internet atomize us into seven billion individuals in gravitationless free-float? Or is going online a solitary act that has the counterintuitive effect of creating and amplifying whole new types of groups – not just mid-’00s flash mobs, but Nazi dinnerware collectors and even religious subsects? I know where you are. You know where I am … and where I’ve been. You know I bought a pair of Lance Armstrong Nikes last month because they were 70 percent off. They know that you just returned a flat-screen TV for whatever reason – wait – they figured it out because your metadata tells them you’ve been fired, or that you just split up with your now ex.

But who are they, and who are you? And there’s all this crazy metadata about you and me and them that’s all being carved and algorithmed into fascinating capitalistic surveillance entities that feed us back to ourselves. And isn’t it weird how oddly disposable everyone’s become labor-wise? Make one flub and you’re out of the game – but wait – where does one go when one is “out” of the game? You can’t really go to the bohemian part of town because it’s gone now. The underground is now up in the Cloud, with its corporeal creators down on Earth trying to enter the grid as little as possible while, at the same time, they’re as deeply addicted to the Internet as is anyone else whose brain has been neurally structured by its interfaces and patterns.

Douglas Coupland, “She’s A Good Girl Loves Her Boyfriend”, 2014

Douglas Coupland, “She’s A Good Girl Loves Her Boyfriend”, 2014

Everyone on Earth is feeling the same way you do.

One of the powers of art is that it takes the world you live in and reorders it in a new way so that what was once merely the everyday world, becomes an aesthetic experience. Something that was previously invisible is now seen. We can go to thingsorganizedneatly.com. We can visit countless pages of witty and beautiful GIFs. We can go to our Crohn’s discussion group page. We can plot our conversion into jihadi. We can watch incredibly narrow categories of porn. We can look at kittens and skateboard face-plants and real-time or speeded-up railway trips through Norway. We can take ourselves out of ourselves anywhere. We can build a constellation of friends and frenemies and habitual must-see links. Class and bohemianism are morphing in tandem except it’s all in our heads and it’s all in the Cloud and everyone out there walking down the street is clean and well groomed and possibly wearing an ironic T-shirt because wherever you see irony now, that’s where you find “bohemia.”