Scanners

The transition from analog to digital may stand as a neatly canonical source for the shift in how we speak about photography today, but it was hardly the only change in what we take (or took) the form to be.

In the text that follows, Loretta Fahrenholz, an artist working across various filmic and photo media, calls attention to, among other things, a distinct transformation in what we actually seek to record when we take a picture now, the current dynamics of representation (and potential for violation), and the attendant ways in which we’ve come to control (and police) the other through the lens.

The Index

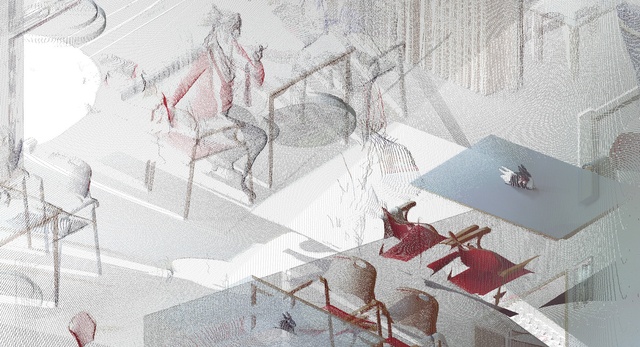

Recently, I was taking pictures in a psychiatric hospital with an industrial 3D laser scanner. To protect personal rights, traditional photography is not allowed in medical institutions. But a room scanner, normally used for mapping property, is not designed to register moving objects. With a 360 degree scope, it records what happens not in an instant but over a sustained period of time, making a full revolution in 5 to 30 minutes. Though individual identity in the resulting 3D point cloud is inscrutable, the moving bodies still leave a ghostlike trace. This process makes me think of the long exposure period nineteenth-century photography required. I like that the scanner, when put to work, sees something that goes beyond the accumulation of measurement data and produces some kind of index of working and living environments that for legal reasons rarely turn into images.

Bad photography

Loretta Fahrenholz, „kbo-Isar-Amper-Klinikum, dining hall 1“, 2015

Loretta Fahrenholz, „kbo-Isar-Amper-Klinikum, dining hall 1“, 2015

The reversal of the gaze

I sometimes think it’s a bit like the radical ideas of early Romanticism later being absorbed (and diluted) by Biedermeier. In the mindset of the German Restoration, the middle class migrated into the realm of bourgeois domesticity. Maybe when our world subjectively feels more uncontrollable and unstable, a sense of exploration is overpowered by an urge to sedate ourselves with the reassuring details of our everyday routines. There is something very Biedermeier about Facebook and the way it constructs identity.

Another catalyst for the reversal of the gaze might be the increased sensitivity toward the politics of representation that Western (social) media has brought about. Apart from all the positive ways in which this has influenced public discussion, such heightened awareness sometimes tips over into a strange control mentality that produces a rhetoric of victimhood and therapy speak. As a result, a kind of dated morality is creeping back into the imagery and discussions around (pop) culture. It can create very absurd feedback loops, such as the tiresome dynamics between body shamers and the shaming of body shamers.

This policing style can have a restrictive effect, particularly when it results in cries for legal control of free expression; for instance, the Title IX anti-discrimination violation claims made by university students against cultural critic Laura Kipnis for speaking her mind regarding campus feminism and the possible overuse of trigger warnings.

I think this inclination towards caution, a “stay in your place” logic, is also employed in (art) education right now, creating a self-contained system wherein various highly specialized agendas end up merely biting each other’s tails. These micro-trolling dynamics unfortunately encourage an overly anxious climate in which people are afraid to step outside of their assigned patch of expertise. When operating in a fairly obscene system, socio-economically speaking, we have to acknowledge the fact that every position within the system from which we speak will always be cringe-worthy in some way. So there is not much salvation to be gained from an infantile regression into assumed creative “safe spaces.”

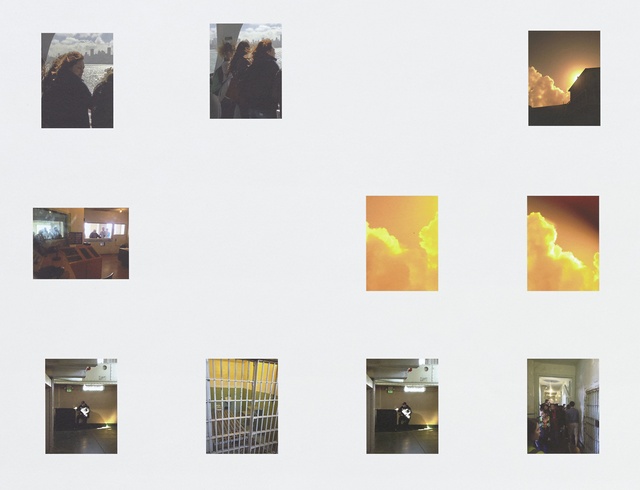

Loretta Fahrenholz, „Recently Deleted 3“ (detail), 2015

Loretta Fahrenholz, „Recently Deleted 3“ (detail), 2015

The freedom of the lost referent

In contrast to imagery in art shows, posted photos seem to work increasingly in the logic of speech acts, images are doing something by their mere appearance. Think of it like a poem, a performance, an utterance of unclear expressions that want to be shared.

Notes

| [1] | Loretta Fahrenholz, „kbo Isar-Amper Clinic, Art Therapy 1“, 2005 |