Beyond the Margin Scott Roben on Anna Bella Geiger at MASP, São Paulo

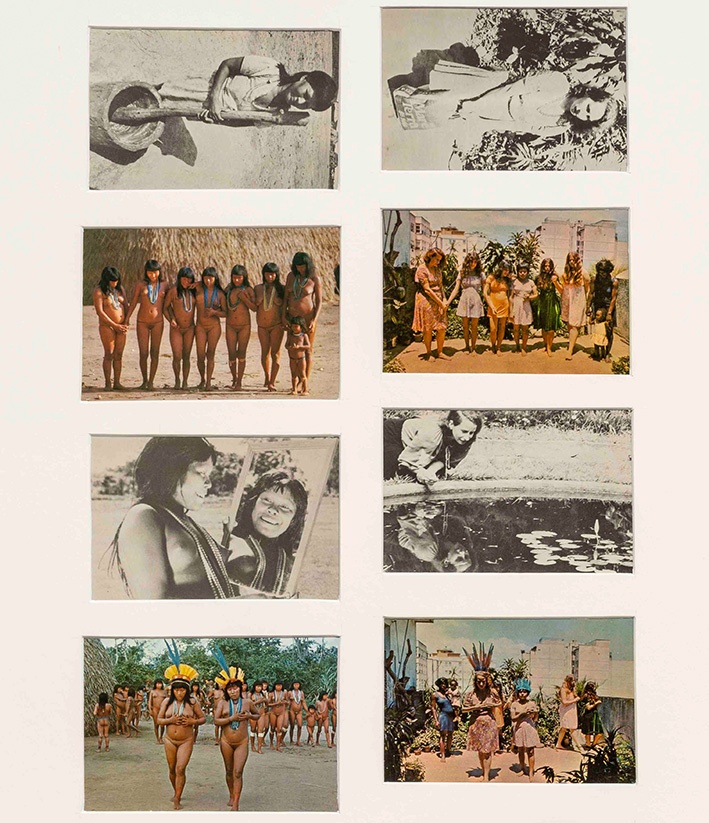

Two black-and-white postcards, side by side. On the first, a woman wearing a light, knee-length dress looks away from the camera, her face in shadow. She twists to the side, and her weight falls on her right leg while her left knee bends slightly, the sole of her foot lifting off the ground as she sweeps the earth beside a palm leaf-covered hut. On the second postcard, a taller, lighter-skinned woman in sandals stands on the street in front of a stone building in Rio de Janeiro. She performs the same action, in the same pose. The backs of the cards are identical except for the caption information, which appears in Portuguese and in English. The English detail on the first reads: “Bororo indians/Mato Grosso. Central plateau.” The second: “… with my lack of skill as a primitive man/Anna Bella Geiger.”

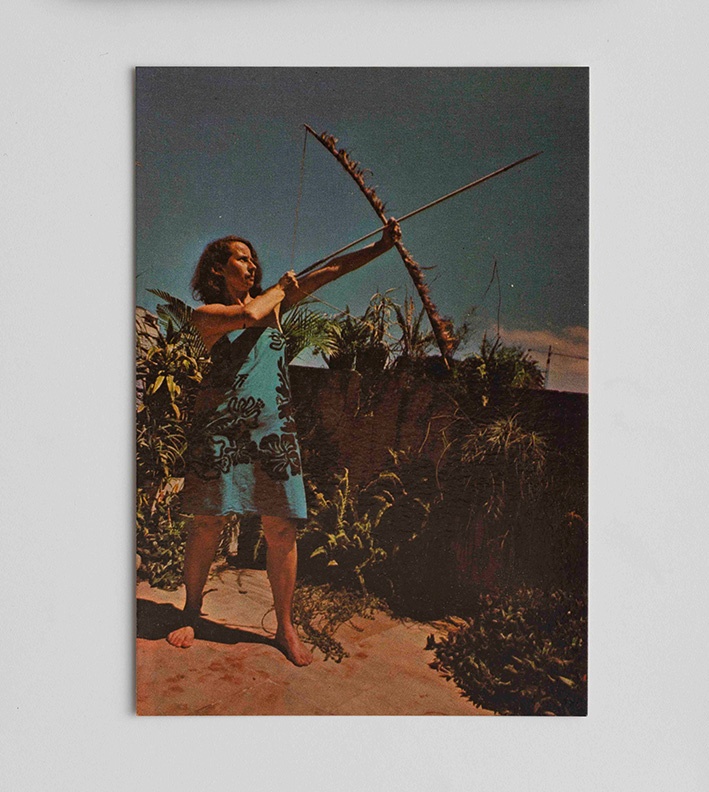

It’s a volatile gesture. These are one pair of images from Anna Bella Geiger’s series Brasil nativo/Brasil alienígena (Native Brazil/Alien Brazil), the work from which the current survey of Geiger’s work at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo takes its title. Along with her daughter and friends, Geiger restaged scenes of the Bororo people depicted on postcards from the mainstream Brazilian news magazine Manchete. She made them between 1976–77, about a decade into the 21-year rule of Brazil’s military dictatorship, during which period the country’s indigenous communities were subjected to some of the government’s most horrific crimes.

In handling what are essentially propaganda images (the postcards proudly present the Bororo people in an idealized vision of contemporary Brazil, while also reproducing the colonial myth of the tropical paradise), Geiger is deft: she posits a binary – native and alien – that erodes as soon as it manifests. The linchpin is the specificity of her own body and autobiography, as well as the obvious fact that total replication of the original is futile. This causes all kinds of strange ruptures, particularly where the images don’t align: her choice of sandals, the frustrated stare of a participating toddler, the edge of an acrylic table jutting into the frame. Such moments of surplus work in a manner opposite to the Manchete postcards’ reductive frames, unsettling both sets of images. At the same time, most of the figures in the postcards are women pictured near homes, sometimes cleaning or caring for children. Gender and particularly gendered labor surface as counterpoints to the title’s dichotomy, agitating it even further.

What does it mean to be native or alien, and whose interests do such distinctions serve? (There’s wit in Geiger’s posing of the question – like “alien” in English, alienígena carries extra-terrestrial connotations.) As an alternative to this opposition, Geiger’s images point to a space of common marginality.

Geiger was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1933 to Polish Jewish parents who had immigrated during the previous decade, shortly before a larger wave of refugees began arriving from Europe. Among the latter was Fayga Ostrower, a prominent abstractionist and socialist whose family Geiger’s parents met at a cousin’s wedding. [1] Geiger would later study under Ostrower, absorbing her approach to the graphic arts as democratized and distributable, and therefore more politically viable as a means of producing images. The drawings and prints that form the basis of nearly every body of work in this exhibition attest to the depth of the impression.

A major early achievement was her inclusion in 1953, and at the age of 20, in the 1a. Exposição nacional de arte abstrata (1st National Exhibition of Abstract Art) at the Quitandinha hotel in Petrópolis, where she appeared alongside concrete and neoconcrete artists like Ivan Serpa, Antonio Bandeira, Lygia Clark, and Lygia Pape. Following the military coup in 1964, however, Geiger abandoned abstraction: “Something within the ‘isms’ and within that aesthetic didn’t make sense anymore.” [2]

Anna Bella Geiger, “Brasil Nativo,” 1976-77 (detail)

It’s at roughly this point in Geiger’s career that the exhibition at MASP begins. In the years following 1964, the path Geiger took (as she grappled with the crisis of an authoritarian state, the complexities of Brazilian national identity, and the weight of Global Northern cultural hegemony) led her through an astonishingly diverse range of formats and motifs: from drawing and painting to film, maps, land art, appropriation, artist books, and self-portraiture. These are divided into seven bodies of work that are distributed around the exhibition halls of the MASP as well as at the SESC Av. Paulista, São Paulo, like islands that can be visited in any order.

Throughout her varied production, an understanding of the body as both a locus of identity and a disruptive force remains a constant. You can already see it in the earliest pieces on view. In the late ’60s, Geiger’s practice veered toward the figurative, or rather what critic Mário Pedrosa termed the “visceral,” [3] as she began producing leaky compositions in watercolor, ink, and aquatint on paper resembling organs, situated in fields of negative space that enclose but also penetrate, even slice them. Bleeding and strewn about the picture plane, they speak not only to corporeal but also societal undoing.

One of Geiger’s most extensive projects is her ongoing work with the map as subject, where bodily interventions and other distortions frequently create ruptures in a form that is still laced with colonial ideology. Among these works, the body enters most clearly in those that originate in drawing, where the intimacy and specific touch of the hand rub up against the map’s pretense to rational order. In El Primer Mundo (The First World, 1977), for example, Geiger drafts a map of the world where the continents have been tilted and realigned along the globe’s horizontal axis, their forms filled in so vigorously with graphite that they pucker, like aged, leathery skin. And her own skin enters into the frame in a series of films titled Mapas Elementares (Elementary Maps, 1976), where the camera peers from behind her bare shoulder as she draws.

Nowhere, perhaps, is Geiger’s body more potently implicated in a refusal of the map’s totalizing logic than when she literally ingests it in her iconic O pão nosso de cada dia (Our Daily Bread, 1978), a series of six postcards and a paper bread bag that document Geiger eating the centers out of two pieces of bread, leaving behind holes in the shapes of South America and Brazil.

Geiger’s ability to operate within indeterminacy (what exactly, for example, are we to make of the fact that the contours of those chewed-out holes look so similar?) is part of what makes her work so formidable. Visual elisions, rhymes, and wordplay crop up everywhere, allowing for resonances between disparate motifs that give the work a sense of gnawing difficulty. It was around 1980 that she began to work with a dichromatic pattern based on cloud formations. [4] Printed in green and white, it also resembles a world map, or perhaps a military camouflage pattern – the latter suggesting its own model of one thing becoming another, a model inflected with threat. It was the primary element of the immersive installation Mesa, friso, e vídeo macios (Smooth Table, Frieze, and Video), which she mounted at the 16th São Paulo Biennial in 1981. It also featured in two videos there: Quase mapa (Almost Map, 1981) and Quase mancha (Almost Stain, 1981).

The exhibition is full of such “almosts,” where Geiger replaces the signs of a dominant order with shrewdly altered substitutes, challenging their inevitability by opening them up to subjective association. Like the faltering simulacra of Brasil nativo/Brasil alienígena, they leave you with a sense not just of dissolution, but of nascent potential. As if, in the moment when the paradigm flickers, you can already glimpse new lines of relation being sketched.

Walking through the exhibition, it’s difficult not to feel the work’s urgency redoubling in light of the contemporary moment, when extreme-right politics are surging not only in Brazil but around the world. Geiger cultivated her practice as a response to the question of art’s role in a moment which – though far from identical – seems to echo our own. Her longstanding insistence on troubling categories, as well as on the complexity of the particular, may help us understand not only the conditions that brought us here, but also ways of moving forward.

“Anna Bella Geiger: Native Brazil/Alien Brazil,” SESC Av. Paulista/Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, November 29, 2019 –March 1, 2020.

Scott Roben is an artist and writer living in Berlin.

Title Image: Anna Bella Geiger, “Brasil Nativo,” 1976-77 (detail)

Image credit: Eduardo Ortega

Notes

| [1] | Anna Bella Geiger, interview by Adriano Pedrosa, “Uma história toda ligada: entrevista com Anna Bella Geiger,” in: Anna Bella Geiger: Brasil nativo/Brasil alienígena, exh. cat., Museu de Arte de São Paulo, 2019, p. 73. |

| [2] | Gabrjela de Laurentis, “Nota biográfica,” in: Anna Bella Geiger: Brasil nativo/Brasil alienígena, p. 267 (author’s translation). |

| [3] | Mário Pedrosa, “Anna Bella Geiger,” in: Correio da manhã (Rio de Janeiro), February 6, 1968. |

| [4] | Anna Bella Geiger, interview by Zanna Gilbert, “Anna Bella Geiger, Part 3: On Mapping,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0qcCb7rFwHU. |