GARY INDIANA (1950–2024) By Bruce Hainley

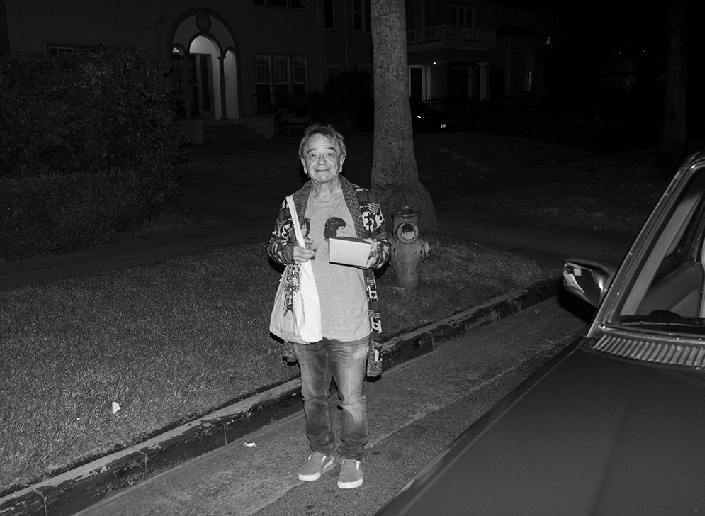

Gary Indiana in front of his Los Angeles apartment building, 2021

On the phone he would often break into song. The last time he did this it was Alvin and the Chipmunks’ rendition of “Ragtime Cowboy Joe,” sung in a chipmunk voice. He would sing songs by Dory Previn and quote her lyrics, some of which scored his art and essays, but his signature number was “Who Taught Her Everything (She Knows).” Trouper, he knew all the songs of Funny Girl.

He changed his name to Gary Indiana because he thought his parents might see an obscure film journal where he’d published a little essay with an obscene title. A friend suggested the alias. “I was smart but not sophisticated. It wasn’t Hoisington but Gary that bothered me. Why did my parents call me Gary? Probably because Gary Cooper was popular when I was born.”

When he was feeling blue, he often watched Color Me Kubrick. John Malkovich plays the perfectly named Alan Conway with delicious, faggy lubricity. For a few years in London in the 1990s, Conway impersonated Stanley Kubrick, looking and sounding nothing like him, for free bar tabs, hotel rooms, comely tosses with gullible male beauties, and, probably, no end of fun. The last text I sent Gary, on Tuesday, October 22 at 14:50: “It’s Stanley Kubrick. I hope you’re feeling better. Tried ringing you just a minute ago.”

“I didn’t ever believe in god, but I’ve had moments in my life when I felt at one with the universe,” Gary told Jason on a really deep late-2019 broadcast of Hollywood Freeway.

“When I lived [in LA] in the ’70s, and I worked at Legal Aid in Watts and at the Westland Twins at night, selling popcorn, I used to drive up to Malibu Canyon sometimes, just to get to this one spot, where all you could see was the ocean and the sky – and I’d always be playing [David Bowie’s Low] in my car. It was the only peace that I ever actually felt during that time. Just peaceful. I think it’s one of the most beautiful things that Bowie ever did. I mean, I love everything by David Bowie. Everything. David Bowie was so important to me when I was […] 19, 20, 21. I never liked gay stuff [cackling] … but I loved the androgyny of that whole glitter period, glam rock period, so much. It seemed like it was for people like me rather than people like them [cackling]. My mother told me once that when I was a child if Judy Garland ever came on the television that I would run into the kitchen and hide under the kitchen table [laughing]. But Bowie I really had a response to …”

Lifelong insomniac, Gary reported from Arles how much he liked watching Florent Hurel, “this lovely man,” who, “every very late night and early morning on French TV, for well over an hour […] just sits on a sofa reading books aloud. He makes wonderful little gestures with the fingers of his free hand. Sometimes he crosses his legs at the knees. Sometimes he holds the book in both hands. He reads as if he’s reading these books for the first time, it’s not at all a theatrical performance. Yesterday it was Jane Austen, Persuasion. Today it’s Irène Némirovsky and Apollinaire.”

Gary Indiana, Florent Hurel on TV, 2021

In one of his last emails, sent barely a week before he died – and he did not think he was going to go so suddenly or soon: he’d rented an apartment in Paris for the spring and was planning to shoot a short “Godardian” movie based on Balzac’s Ursule Mirouët, starring the glamourous equestrian neighbor of a friend in Arles – an email almost certainly sent to others and that might have been part of a new novel that had been frustrating him but with which he’d finally made headway, he wrote:

“All these books piled up on my desk. The Island of Fu Manchu, Wuthering Heights, Death on Credit, The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, Victor Serge Notebooks 1936–1947, Moll Flanders, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Emperor Fu Manchu, a biography of Diderot, A Savage War of Peace, Mau Mau and Kenya: An Analysis of a Peasant Revolt. The answers are in plain sight. The ones we’re given to answer. Some we know we’ll never know.”

Witold Gombrowicz’s Diary, Charles Francis Adams Jr. and Henry Adams’s Chapters of Erie (“the most astute and concise book ever written about American capitalism and its political reverberations”), Jane Bowles’s Two Serious Ladies, all of Jean Rhys – aspects of each of these shine in different parts of his work and provide answers, too. What interested Gary about Ursule Mirouët was her complete indifference to money. “For which, in the end, she’s rewarded.” His film would be a retort to current vulpine appetites for celebrity-notoriety, “currency,” acquisitions, the cult of the name, and of prizes, on which certain artist- and writer-types work incessantly, clearly harder than they work on anything else. Several were named, with a derisive laugh.

The morning after he’d reminded me that his favorite thing in the world was The Boy Friend (Ken Russell’s 1971 musical phantasmagoria, a singing-through – as working-through – of the delirious glory of Hollywood musicals: dawn-bright Twiggy, smoky-voiced Georgina Hale, wicked Antonia Ellis, Tommy Tune incomparable, the entire cast, delirious sets, and costumes, all so heartbreakingly glorious and gossamer-winged), on October 7, 2024, under the subject line “and, on the other hand,” he sent, in separate emails, scans from Jean Guéhenno’s Diary of the Dark Years, 1940–1944, entries from December 8 and then December 23, 1940. In the first, Guéhenno prompts himself not “to […] be destroyed by propaganda, invaded by ‘society’”; in the second, he laments: “What I have seen the past thirty years is a real enigma to me. How did the milk of human kindness turn into the blood of battles? How, out of love, have we ended up killing each other so conscientiously?” Between those two emails, Gary sent a Grandville caricature, delineating scenes in the land where preposterous differences in class rank are made visible by differences in size, elites elongated as ostriches, workers squat as hedgehogs. He trusted that he didn’t need to mention the upcoming elections in what he’d long ago called the “excremental empire,” its funding of Israel’s bombing of Palestine, the horrid interrelatedness –or repeat the point Céline makes in North that Gary thought couldn’t be made often enough: “Wars are fought by poor people for rich people.”

Marx’s fine-tuning of Hegel’s facts and personages appearing, so to speak, twice – the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce – has been getting a lot of play lately, but no one seems to have mentioned that those two modes have become cruelly simultaneous. Gary’s writing speaks to holding contradictory ideas, as well as contradictions of an artist’s life and art, in one’s head at the same time, a skill almost totally obliterated by current easy absolutism. He allowed things to steep in their murky complexity and confronted the situation with ferocious, gimlet-eyed intelligence, moral outrage when needed, and, much of the time, with lunar humor.

For a few months in 2019, Gary was considering writing a long essay on Harlots, Moira Buffini and Alison Newman’s smart period drama about brothels in Georgian London, based in part on historian Hallie Rubenhold’s The Covent Garden Ladies. There was little about Harlots that didn’t touch a deep vein of his aesthetic and intellectual passions: 18th-century literature, plunder’s history, the dynamics and mental weather of sex workers. He preferred Harlots to The Crown. “I think The Crown could be improved any number of ways. Why not have the Duke of Windsor smother his mother with a pillow? Couldn’t Elizabeth have a lesbian affair? Churchill could be shown giving Stalin a blow job. Hitler might be seen fucking the Duchess of Windsor in the ass while getting his own ass fucked by Goering. This would simply be poetic license.”

Hedi, Gary, and I all had an immense appreciation for the work of writer, actor, and filmmaker Jacques Nolot – particularly the films he directed, especially Before I Forget (Avant que j’oublie, 2007). Because Nolot was someone whose pursuits we often turned to in conversation, Hedi forwarded me Gary’s email about the film. A key part:

“One typical attitude towards hustlers among supposedly upper-class people is that they’re dregs of humanity with no future – one thing I loved in Before I Forget was that all the principals were or had been hustlers, gigolos, the old ones weren’t depicted as predatory, the young ones weren’t ciphers – Of course as gay histories become more commonplace it’s more common to find it acknowledged, without as much moralistic surprise as in the past, that many, many well-known gay men worked as hustlers at one time and/or routinely paid hustlers for sex – ‘hustlers’ is maybe an unfortunate term – I can’t recall what I was reading a few days ago, but it was a story about some writer, artist, some person of interest, and one nice aspect of the article was, that in the context of it, the guy paying everyone he had sex with was presented as completely ordinary, normal – & that was so lovely in the movie, too. The unobtrusive way the money was exchanged, even less emphatic than the glancing way the guy paid the psychiatrist by leaving a few bills on the table. I read some of the ‘mainstream’ old reviews of Nolot’s film – positive for the most part, but for mostly wrong reasons – what we find natural, they think of as amazingly courageous, disturbing, and also pathetic to show – the aging body, etc. – which, given how many received ideas tend to get packed into a review of anything, it is. But I think it’s more courageous to show that auction near the end, without portraying the people bidding on those things as horrible, or insensitive, or what have you. That’s how life is …”

Sometimes Gary would send me screengrabs of texts between him and some trick:

Guy: … many pay to eat my shit

Gary: I’m sure they do. I am not into that although they say it cures various ailments, chiefly narcissism.

Gary: So for four hundred dollars someone gets to eat your shit

Guy: correctomundo

Gary: I will call or text you some day in the coming week, even maybe this weekend that’s already started, and set up a time and send you my address. Please don’t make me eat your shit even if it seems like a good idea.

Guy: no problem see you soon

Let’s be clear that the sexual in his writing is never merely titillating, if it is ever that at all. It is a way of dismantling rote thinking about relationality, received ideas of what is exchanged between people in intimacy.

“I want to be the hole he wants to fuck, but, why, exactly. Because I want sexual things to stay at a certain place, not spill out into role-playing and learned sentiment, I want this guy’s boyishness and the feelings he has immediately before, during, and after the sexual connection, but not most of what goes on outside that connection, I don’t want his slop, his emotional retardation, his bullishness, I don’t want his masculinity except in the form of his hard dick. I want his macho expectations of life to be disappointed and I want my ass to be his consolation prize.”

I knew Gary well enough to know that he put, when typing, two spaces after a period between sentences, old school, but also that many people knew him better and/or longer, many times over, than I did. Barbara Kruger. Patrick McGrath. Renata Adler. Larry Johnson. To name only a few. I’d much rather be reading something they recalled. Actually, I’d rather be reading something Gary, still alive, just published.

The first time I met him, in a taxi with Richard Martin, the late, great, gone-too-soon editor, writer, scholar, and Met Costume Institute curator, Gary regaled us on our way downtown with a hilarious and incredibly louche story, freaked with sapphism, about Lauren Hutton. Gary was very funny, had few equals as a raconteur, and, also, as too many have recently been too quick not to mention, he was often touchingly, almost bewilderingly, kind.

Which doesn’t mean he couldn’t be unnerving. Intellectually. In terms of what he knew and knew in ways that other people didn’t, never did, and perhaps never will again. He was inspiringly well read, from the so-called canon to the most outré murmurings, and a rousing intellectual perhaps as only someone who was acutely unacademized – I’m tempted to say uninstitutionalized – could be. Vividly candid self-starter, he didn’t like stupid or calculating people. He had earned the right to be difficult – and most of the time he really wasn’t. Or not without reason. He’d tangoed with difficult people and knew that often some have difficult but crucial truths to convey – in complex sentences, in scintillant turns of mind, as art – and we ignore or abandon them at our peril. He didn’t acquiesce to so many of the hackneyed ideas of what constitutes importance, cultural and otherwise, didn’t acquiesce to what so many deem “success.” Certain modes of living and thinking are being pointedly, viciously obsolesced, have already been obsolesced, as we continue to entertain ourselves into oblivion. Embracing the difficult, the off-piste, Gary lived a more kaleidoscopically varied and colorful life than most. A line from his beloved Werner Schroeter’s Eika Katappa repeats at many points in his writing: “Life is very precious, even right now.” It appeared first in 1982, at the top of Gary’s grand early essay on Schroeter’s movies, and then later, in 1994, as one of two Schroeter-related epigraphs that kick off the pornographic romp of Rent Boy. Precious, not easy.

After Vile Days was published, he sent me this afterword:

“I keep forgetting to mention, though it’s always present in mind, in these things, that at the same time this mini-me artworld fantasia was unfolding, people who were just as gifted, just as interesting, and just as worthy as the people who were, in fact, being regarded as such, were DROPPING DEAD, day after day, week after week, while the circus did its cartwheels of dubious coinage … perhaps it’s still an imperfectly repressed gash in the ? something of time … but it was so much the wallpaper of that period, the Lady in the Radiator, the unspoken of spoken of every day … how soon we forget.”

Via the art of the still deeply underappreciated Meg Webster, in particular Hollow (1985), that sculpture that was “an earthwork, a garden, a grotto, a microcosm,” Gary wrote that Webster’s intervention “takes the transience of everything, including itself, cheerfully in its stride.” In this strange thing, it is “possible to understand the futility of art without giving up on it, because the work is joyful and ‘irrelevant,’ hard labor personified and cosmic pleasure.” Then he ended with this gentle notice: Hollow “makes you feel that living and dying are important processes to pay attention to, and that everyone is always doing both. You could die even if you belonged to the country club, and you could live even if you didn’t.”

He cared deeply about his friends, about friendship, and was wary of admirers. On the phone: “Admiration is just the flipside of contempt.” We were talking about Resentment. “I’m such a cunt – even to people I’m really really fond of – in that book.” Pause. “You know Jean-Henri Fabre’s book on the dung beetle? Everything from Resentment comes from that.” Then he broke into “Who Taught Her Everything (She Knows).”

He was one of the last hotlines to a way of being almost entirely eclipsed. What he wrote about Pasolini glosses some of his intellectual and life project:

“Pasolini identified with the losers of the global economy. He used his sexual difference as a tool of analysis, a goad to empathy. In this sense, his homosexuality was a far more potent quantity than the open gayness of any number of contemporary writers, film-makers, actors and CEOs. A different quantity, certainly, than the homosexuality of people clamouring to join the military, serve in their nation’s intelligence services and police forces, enter the clergy or participate in the sham of family values by lobbying for marriage and adoption rights.”

Gary’s great subjects are America and so-called masculinity – and their cons. He agreed with Grace Slick, who, he told me, once declared, “I’d rather have my country die for me.”

He hadn’t eaten anything all day the last time we talked. He’d fallen asleep under his desk and couldn’t get up without pain. He dreamed of fixing himself a big “Scottish” breakfast – I don’t know why Scottish – eggs, bacon, tatties, smoked haddock, sausages, porridge, scones. He talked about broiling things in the oven and eating them all up, relishing even the description of this feast. He was so excited to eat the next morning, but he just didn’t have the energy to make the meal now.

Larry called to tell me Asha had called to tell him that Gary had died. I’d called Gary earlier, the day before, to check up on him and had a sinking feeling something was wrong because it was the second time I’d called in 48 hours to no response.

His favorite thing in the world was The Boy Friend.

In one of our summer conversations, he told me: “Death is not the worst thing that happens, it’s just the last thing that happens.”

Bruce Hainley lives in Houston, Texas.

Image credits: 1. © Laura Owens; 2. Courtesy of the Estate of Gary Indiana