Commited Occidentalists. Philipp Ekardt on Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho at Mathew, Berlin

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, installation view

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, installation view

One wonders what initial reaction Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho might have had when the organizers of Berlin’s Mathew Gallery first approached them with the idea for this exhibition, a show that would involve multiple artists and take as its common denominator their shared non-differentiated ethnicity – in cruder terms, a show of “Asian” artists only. One could also speculate about the potential repercussions of such a proposal, had it been articulated with unmitigated clarity in one of the art worlds of New York or Los Angeles, for example, where the question might have echoed with the self-cognizance of certain local groupings. (And here one ponders also how such a wide array of potential resonances failed to carry over into the increasingly international, yet nevertheless predominantly white context of the Berlin scene, where race is typically still treated as a non-issue, or a ‘critical special interest’ at best.)

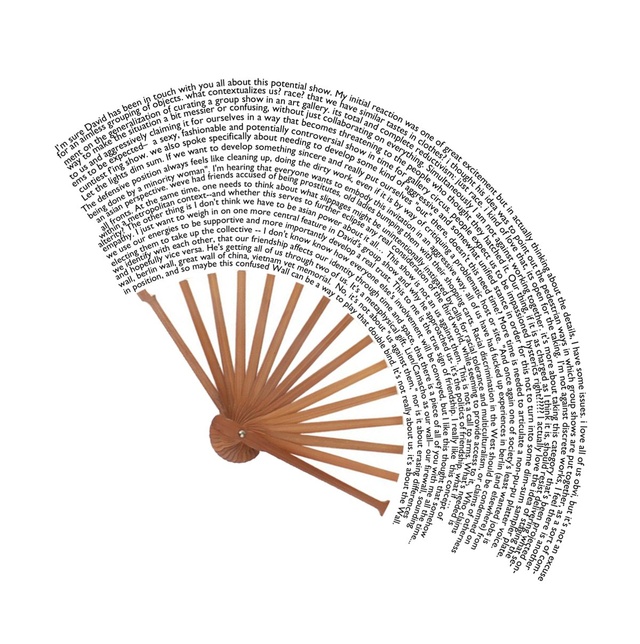

How to respond to such an interpellation? Is there an option besides merely rejecting said problematic proposal? Shades of possible alternatives appear recorded, it would seem, in the image circulated as the show’s invitation (subsequently posted to the gallery’s website) which contained text extracted from email-exchanges between Lien, Camacho and the show’s other participants (Lisa Jo, Margaret Lee, Carissa Rodriguez, Amy Yao, Anicka Yi) arranged in an arch that radiates from a photograph picturing the central linkage of a tourist’s “oriental” fan: “My initial reaction was one of great excitement but in actually thinking about the details, I have some issues. I love all of us, obvs, but it’s not an excuse for an aimless grouping of objects. what contextualizes us? race? that we have similar tastes in clothes? I thought the idea was to point out the pedestrian ways in which group shows are put together, as a sort of comment on the generalization of curating a group show in an art gallery. Its total and complete reductivism: just race. i kind of love that, it’s open for the taking.”

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, invitation/press release

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, invitation/press release

There are of course many situations in which this “total and complete reductivism: just race” could take a much more violent form; an experience that the text also mentions: “all of us have had fucked up experiences in berlin (and elsewhere) from an asian perspective. weve [sic] had friends accused of being prostitutes [n.b.: why being hailed as a prostitute would count as an ‘accusation’ is a different matter], old ladies bumping them with their shopping carts.” Hence, the question here seems less about the latency of the problem of race/ism in its primary form – that the gallery’s request is an “impossible” invitation; that is clear and all in the open – but rather, how that category is reformatted through the logic of the art system, which potentially employs it as the possibly dumbest common denominator. The gallery’s invitation to Camacho and Lien could even read as a revelatory reduplication of any number of curatorial maneuvers; as a charade, as a flirtation with the frivolous, as a reenactment – but also by drawing attention to the ways in which art is shown according to categories of cultural, national, or even racial adherence: for instance, “German Art.” What would that be?!

Photo: Louis Vuitton/Annie Leibovitz, 2011.

Photo: Louis Vuitton/Annie Leibovitz, 2011.

Lien and Camacho’s response can best be described as a symbolic retort – a gestural appropriation of various stylistic tropes, and as a concomitant formal inventory, at times employed to connote “Asianicity,” or “Eastness,” to use Barthesian vocabulary. [1] One could also call their response, and the entire show, an exercise in rhetorics. The installation that made up the exhibition consisted of imitation Berlin Wall slabs built from a mixture of materials that included, among others elements, papier-maché, lumber, transparent foil, and rice glue. With Lien and Camacho in charge of the work’s physical execution the two covered these segments with scribbles, paroles, graffiti, and other treatments, relying in part on suggestions from the other artists involved. The slabs were arranged in a semi-circle that cut through the exhibition space, creating an arched formation again recalling the structure of a fan. But there was yet another congruence between that object and the installation: upon closer inspection the wall’s strange, almost mildewy materiality appeared porous and light, which is to say not unlike that of the handheld fan itself; a counterpoint to the heaviness of the piece’s architectural and political reference. Motioning towards the wall that, yes, once partitioned the city into West and East, the installation stood in Mathew displaying all sorts of political demands and imperatives, sometimes also just mere observations, combined with a number of visual motifs, such as mouths wide open as if shouting political slogans, or a very large Hello Kitty face. A scroll ran down one segment: Racial discrimination in the west should be condemned on all fronts. Other statements read, Erase My Face, The Income Gap. Rote Angst (a translation of the American “Red Scare”); Reject Suckcess; and, with a tip of the hat to two issues in contemporary art and critical theory: Speculate My Dick and Post-Net Sucks. All told, it looked as if a more refined version of Berlin’s East Side Gallery had been set up on the premises of a gallery that derived at least some portion of its initial credibility from a symbolic decision to open in Berlin’s western districts, here Wilmersdorf. The work, by evoking the paraphernalia of political protest and the folklorization of the memory of political struggles, in turn exuded a composite sense of interest, bemusement, and ennui.

One of the slabs displayed the slogan, Comme des Orientalists – its various entendres riffing on several pertinent contexts: first, that of Orientalism – the phenomenon itself. The headline also called up Edward Said’s canonical, eponymously titled 1978 study that presented the first extensive critical analysis of said phenomenon. [2] Like in the case of their May 2014 performance at Hamburg’s Golem club “G-SPVK SPEAKS BITCHES ON ICE” (with Christian Naujoks), the reference hence targets both the phenomenon and its discursive critique. In the case of the Hamburg performance, the reference to discourse was coded into the allusion to Gayatri Spivak, another founding figure of postcolonial studies, who is here also invoked by the purported stylistic tension between the register of academic discourse and a manner of speaking or writing that more or less convincingly gestures towards a ‘radical’ pose by attempting to sound ‘ghetto’, which the theorist, activist, and University Professor at Columbia has turned into her trademark. Lien’s and Camacho’s prowess for communicatively nailing such issues shows up again in the this performance’s flyer, featuring a photograph of the actress Angelina Jolie – she, of the humanitarian rights trip into Cambodian backwaters, where she posed on the deck of a wooden barge for Louis Vuitton, her LV Alto tote bag slung over one shoulder – her salary for the resulting LV campaign undoubtedly donated in full to a good cause. In the image on Camacho, Lien, and Naujoks’s flyer, Jolie kicks back on what looks like a luxurious bed in a hotel suite, her arms casually crossed behind her head – a posture also taken by a little ‘Asian’ boy to her right who, media consumers will easily recognize, is Maddox Chivan (né Rath Vibol), Jolie’s adopted son from a Phnom Penh orphanage.

A further reference in Comme des Orientalists points, obviously, to Comme des Garçons, the fashion house, founded by designer Rei Kawakubo, whose works were instrumental in reprogramming Parisian prêt-à-porter into the 1980s system of ‘post-fashion.’ After showing her designs in 1981 at the Paris Semaine de la mode, Kawakubo’s mostly black, physically ‘worn,’ ‘torn,’ radically wide and asymmetrical designs, like those of her colleague Yohji Yamamoto, were disgustingly labeled by some among the Western fashion press as ‘Hiroshima Chic’; this, another act of (negative) Japonisme or inverted Orientalism that reproached the non-Western designer-subject with failing to conform to projected notions of ‘elegance,’ while missing out on the path-breaking investigation of the very concept of elegance that Kawakubo’s dresses actually performed. [3]

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, installation view

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, installation view

In evoking such a multiplicity of levels – political, discursive, stylistic – Camacho and Lien’s show was savvy, educated, perhaps even studied and academic. One might go so far as to detect a whiff of weariness in it, a slight shrug in the face of all these referential riches. The maneuvers it engaged are necessary. The problem of ‘race’ exists. But the virtuosity with which these referential and stylistic moves are executed suggest that we have carried out similar ones for more than a good while. The show was titled “Who Do You Love,” and within the intricately constructed architecture of references and rhetorico-positional ripostes that question seemed to imply an impossibly firm affective positioning were it not for that one sentence: “I love all of us, obvs, but it’s not an excuse for an aimless grouping of objects.” The release further states that “if connectivity defines the paradigm that continuously disappoints, perhaps it’s because we forget that a point of contact is also a point of separation. To view a wall begs the question of how you stand in relation to it. [4] Who do you love?” Given the show, these sentences must be considered another rhetorical move. Connectivity and relationality seemed only second to third order concerns in a complex set of maneuvers that skillfully evaded articulating the central question: “What’s your stance?”

The Intangibles of Collaboration (Addendum): An earlier version of this text suggested that Lien and Camacho also work independently. They have responded to clarify that they always collaborate. The original text also stated that Lien and Camacho wrote the fan text. It was in fact composed by them, but using language extracted from an email chain between all of the show’s invited participants. Further changes from the initial version include a description of the wall installation, which had previously been described as with: "each participant assigned one module, the two received instructions from the other artists on how to cover these segments with scribbles, paroles, graffiti, and other treatments."

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho, “Who Do You Love”, Mathew Gallery, Berlin, May 2 – June 28, 2014

Notes

| [1] | See, for example, Barthes’s elaboration of the concept of “Italianicity“ in his Mythologies, New York 1972. |

| [2] | Edward Said: Orientalism. New York 1978. |

| [3] | On CdG’s appropriation and inversion of orientalism, as well as Kawakubo’s investigation of the concept of elegance see the chapter “Ex Oriente Lux” in Barbara Vinken: Fashion Zeitgeist. London 2004. For a general documentation see the catalogue Future Beauty. 30 Years of Japanese Fashion. London 2010. |

| [4] | It cannot go without mention here that the citizens of the GDR, when viewing the wall that Lien’s and Camacho’s show symbolically resurrected, were faced with a limited choice of options for how to relate to it, to say the least. |