THREADS THAT INTERTWINE, BREAK, AND REMAKE TISSUES: PRACTICES OF CONNECTION AND CARE OF LIFE By Imayna Caceres

Imayna Caceres, Pêdra Costa, Marissa Lôbo, and Verena Melgarejo Weinandt, “Offering station,“ 2015

We live within systems of dispossession and traumatogenic [1] structures of oppression which produce stories of loss, pain, and transgenerational trauma. I focus in this text on modes of being with others – human and non-human – that emerged in my migration experience as binding connections and repairing lessons concerning acceptance, community, and kinship. In this attempt, I employ autohistoria-teoría, which was conceptualized by Gloria Anzaldúa as a form of theorizing in which personal experiences, social protest, poetry, and one’s personal and collective history – revised and in other ways redrawn – become a lens with which to reread and rewrite existing cultural stories. [2] For Anzaldúa, autohistoria-teoría allows us to “expose the limitations in the existing paradigms and create new stories of healing, self-growth, cultural critique, and individual/collective transformation.” [3]

Growing up in Lima with migrated mestizo-Indigenous sociocultural practices from the eastern Andes, I found myself in Austria, uprooted from the modes of life in which I grew up, the affective forms of my loved ones, the sharing of a common history, the beliefs, the sounds and rhythms, the tastes, the humidity of the ecosystems that collaborated in making me. An uprooting that became further destabilized by the experience of racism connected to new structures of inequality, accumulation, and domination, including the procedures of immigration systems within the European Union, and living without the political rights of a citizen, such as the right to elect a political group that looks after one’s well-being. [4] The histories of migration from which I come gave me many insights on ways of belonging, and on being – and feeling – seen as not belonging, neither here nor there. Living in these borderlands of non-belonging, living half and half, [5] brings about what I identify as a denaturalizing of the world one knows, and with it, the realization of it being one of many possible ways of living. A source of instability, this denaturalization can, in turn, act as a ground from which to imagine a flexible transformation of our modes of living. Referring again to Anzaldúa, in the borderlands, one is able to develop the faculty to transit between worlds, practices, and languages, and to act as a bridge between (nature)cultures [6] : “Bridging is the work of opening the gate to the stranger, within and without. […] To bridge is to attempt community and for that we must risk being open to personal, political, and spiritual intimacy.” [7] Here it is important to mention that when referring to the spiritual, I do not wish to make reference to private beliefs or a personal/collective connection to religion. Instead, by spiritual I mean a practical, nurturing relation to a materiality or ecosystem (local and cosmic) that is practiced out of need. A care of the relationships with what keeps us alive, which is the basic condition for our life to exist.

In this new space, I also found myself in the privileged position of having access to fundamental basic services that the majority population of the world does not have, and which I did not have before coming here. In thinking of loss and trauma, it is helpful for me to recognize such ambiguities, and to do so in awareness both of experienced oppression and of our powerful capacities for regeneration.

Recognizing these faculties in ourselves is also a way of relating to complex personhood and to avoid centering the story of ourselves around the damage of the experienced oppression. [8] In “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Eve Tuck identifies damage-based frameworks of research as the attempt to explain present manifestations of oppression by looking at historical exploitation and domination, [9] noting that the potential long-term cost of this approach, to establish evidence of harm or injury in order to achieve reparation, and for which the potential long-term cost is to think of ourselves as damaged. Focusing strictly on the damage that communities face, this approach to social change toward justice creates pathologizing narratives of pain. Concerned about research in Indigenous communities, Tuck opens questions about what the long-term costs of people thinking of themselves as marginalized, oppressed, invisibilized, even when part of a strategy of reparation, can be: “Does exhibiting the wounds hold those in power accountable?” [10] Or do these strategies of denunciation “simultaneously reinforce and re-inscribe a one-dimensional notion of marginalized communities as depleted, ruined, and hopeless” [11] and entirely defined by oppression? Tuck calls on us to learn from and build on the work happening in the communities themselves, viewing this as an opportunity for regeneration, which simultaneously acknowledges historical pain and takes action to reframe it. Thus, Tuck invites us to recognize our histories beyond domination and to insist that research in our communities celebrates our survivance as a capacity to create spaces of synthesis and renewal. [12]

Reflecting on my migration highlighted what I experienced as forms of repair that were connected to a sense of care and renewal. Among others, these included: working in decolonial ecofeminist migrant collectives, learning from the non-human beings in my neighborhood, and processing and grounding the lessons received through my artistic practice.

Collective resistance and regeneration

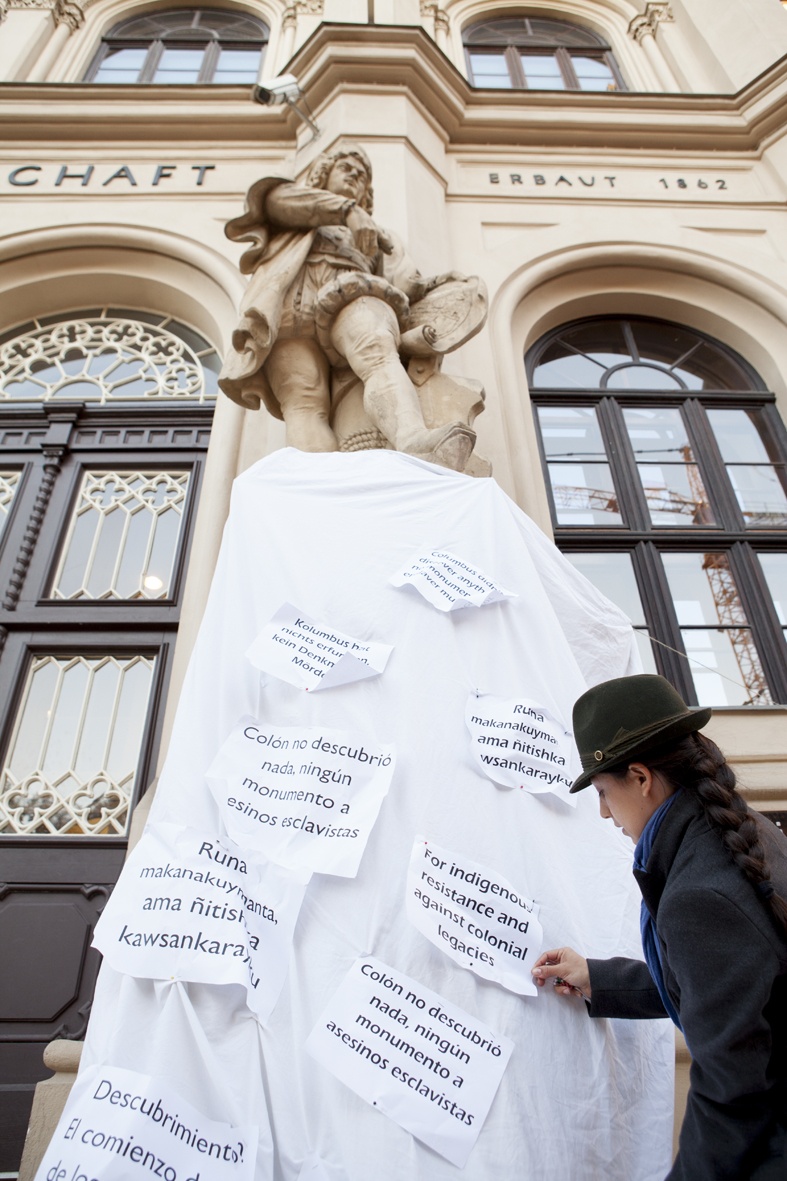

Within the activities of the diasporic Latin American collectives in Vienna, of which I am a part, one can witness the effect of various healing practices. [13] In the gatherings of Trenza, Futuñeras, or Kollektiv Antikoloniale Interventionen in Wien, migrant Latinx women activate decolonial ecofeminist issues about the places we come from, about the places that make us. An example of this is the organizing of actions around October 12 – a date described historically in a colonizing frame as the day of the discovery of America – in different places where Columbus is commemorated. We write the names of the people, past and present, who have defended rivers, mountains, lands, and waters. Through offerings to the earth and rituals that celebrate the aesthetic political practices of our community, we give thanks to the cosmos for providing what we need to live. We invoke rituals we know from the mestizo-Afro-Indigenous worlds in which we grew up and in which subterranean memories come to the surface. We dance to music and performances of cumbia, maracatú percussion, nueva canción, bullerengue, and rap fused with rhythms of Latin American folk and carnival. We come together with other migrant women with whom we resonate, with people who can see ourselves in ways as we see ourselves, who understand the paths and the parts that make us up.

Through these experiences, I have learned to understand ritual as a political technology of reciprocity and reconnection between species that presupposes a world that communicates. Through this signaling of basic relationships with the earth, these rituals become a tool to question the hegemonic orders that have led us to the current anthropogenic crisis and to create a sense of community, allowing a political rethinking of the ways in which we want to live. As a practical reaffirmation of the histories we come from, the memories of these practices are activated through the body, through singing and dancing, creating affective bonds that produce a sense of healing.

Trenza collective, Intervention at a Christopher Columbus Memorial, Vienna, 2018

Redrawing relationships with the non-human

I learned the importance of putting down roots for stability by working and caring for plants, and it was something that happened gradually through my interaction with different non-human beings. Standing on the Danube canal I feel the presence of the river, and something begins to flood me. I bathe in the old Danube and feel the river as a maternal force that embraces every particle of my body. The river embraces me, gives me care, and I feel that I belong. I am overcome with a sensation where I can feel the skin of the world on my skin. I had many other experiences with this mother river and declared it part of my supporting ecosystem that feeds my insides and that is family in the absence of my biological family. The river points out to me the beings that also depend on it: the curtains of reeds, the birds, the fish, the insects, the trees that draw with their roots in the meadow. The river heals me every time I am in its presence, and being with the river becomes a ritual experience.

My connection to the river is one of the instances that deepened my observation of the ways in which other entities live, survive, and thrive in this city. In this, I mindfully approach the beings I seek to know and learn from, thinking of them as people, as communities that are connected in natural-social structures. I pay attention to their ways of living, the roles they play, their relations of cooperation and competition, the way they cope with change, among other particularities.

I grow roots in Vienna and develop a connection with the beings that inhabit my immediate neighborhood. These multiple direct experiences resonate deeply with me: by reencountering llantén or Breitwegerich (Plantago major) and remembering its care work in my personal history, by observing rosemary and lavender withstand each winter, by enjoying the consistency with which daffodils bloom each spring, by recognizing the vulnerability of porous-skinned aspens, by paying attention to the ponds of my neighborhood where toads (Bufotes viridis), along with ducks, rabbits, and crows, make life. Being fully present and relating, and knowing that every sound has a frequency, I learn from other beings by listening to what they themselves say in their actions, in their living, in their choices.

Art as healing practice

Through drawing, painting, dancing, and collective actions, one is able to revise personal experiences, ground the lessons received, and process these insights bodily. The evoked arts and practices, intertwined with rhythmic language, scientific knowledge, and political-spiritual lessons (which are drawn from the ecosystems with which we coexist), contribute to the processing of memories, tracing affectively what is deemed necessary to remember.

Living in realities that are shaped by traumatogenic systems (such as disaster and racial capitalism, antimigration populism, ecocidal extractivism, and endless war among many others), my intention with this text has been to highlight the ways in which organizing collectively, employing artistic formats and our aesthetics capacities, can support us in our work for (re)generating practices of care of life.

Imayna Caceres is an artist and researcher who lives and works in Vienna. Informed by autohistory-theory, her work focusses on queer feminist thought as well as on concepts of border thinking. It draws on interspecies knowledge production to move beyond dominant scientific discourses.

Image Credits: 1. photo kunstdokumentation.com; 2. © Aunt Lute Books; 3. photo Verena Melgarejo Weinandt

Notes

| [1] | Achille Mbembe writes of capitalism and liberal democracy as traumatogenic institutions, or institutions that produce trauma. Achille Mbembe, “The Trauma of the World and the World as Trauma,” videos-saturday/Keynote lecture delivered at the conference Recognition, Reparation, Reconciliation: The Light and Shadow of Historical Trauma, Stellenbosch University, December 8, 2018, 08:26. |

| [2] | Gloria Anzaldúa, Light in the Dark / Luz En lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 241–42. |

| [3] | Ibid. |

| [4] | Achille Mbembe reflects on race and racism in regard to trauma: “[Race and racism] symbolize above all the memory […] of a trauma whose causes often have nothing to do with the person who is the victim of racism. [...] For it to operate as affect, impulse, and speculum, race must become image, form, surface, figure, and – especially – a structure of the imagination. [...] [P]eopling and repeopling the world with substitutes, beings to point to, to break, in a hopeless attempt to support a failing I. ... Racism consists, most of all, in substituting what is with something else, with another reality. It has the power to distort the real and to fix affect [...]. The truth of individuals who are assigned a race is at once elsewhere and within the appearances assigned to them. They exist behind appearance, underneath what is perceived.” Achille Mbembe, “The Subject of Race,” in Critique of Black Reason, trans. Laurent Dubois (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 31–37. In this regard, I also find valuable José Esteban Muñoz’s perspective on race and ethnicity as “affective” differences, meaning the “ways in which different historically coherent groups ‘feel’ differently and navigate the material world on a different emotional register.” José Esteban Muñoz, “Feeling Brown: Ethnicity and Affect in Ricardo Bracho’s The Sweetest Hangover (and Other STDs),” Theatre Journal 52, no. 1 (March 2000): 67–79, 70. |

| [5] | Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute, 1987), 38–39. |

| [6] | Ibid. |

| [7] | Gloria Anzaldúa, "Preface (Un)natural bridges, (Un)safe spaces." in This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation, ed. Gloria Anzaldúa and AnaLouise Keating (New York: Routledge, 2002), 3. |

| [8] | Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (September 2009), 409–28, 420. |

| [9] | Ibid., 413–15. |

| [10] | Ibid. |

| [11] | Ibid., 409 |

| [12] | Ibid., 422–24. |

| [13] | Kollektiv antikolonialer Interventionen in Wien, “Antikoloniale Widerstände 12. Oktober 2020,” Migrazine 2020/2. |