OBJECT RELATIONS IN SEPIA TONES Isabelle Graw on Birgit Megerle at Galerie Neu, Berlin

„Birgit Megerle: Bond“, Galerie Neu, Berlin, 2023, Installationsansicht

The third time’s the charm: I’m trying to write a review, an exemplary one, if possible, for our “Reviews” issue, one in which I will ideally also reflect on my critical approach. [1] My chosen object is Birgit Megerle’s exhibition “Bond” at Galerie Neu. I thought it was a compelling show, starting with the display architecture. With a staggered arrangement of three temporary walls painted in beiges and grays, Megerle had created an installation that perfectly conveyed her painterly program: the portraits she showed likewise relied on a muted palette of roses and greens that seemed to both put her sitters on the stage and allow them to withdraw, not unlike in some portraits by the painter Sylvia Sleigh. Several motifs in Megerle’s paintings, moreover, hinted at insights of the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, obviously a point of particular interest to me as an adherent of Klein’s metapsychology. The question, needless to say, is: Was it just me projecting Klein’s ideas onto Megerle’s portraits, or are those paintings really a bit “Kleinian”? Also very much on my mind is the fact that, if I’m not mistaken, it was mostly artists, critics, and curators who appreciated “Bond” – it was, however, not met with the same enthusiasm in the commercial sector. I have written the following review in the probably naïve belief that economic developments have not yet completely detached themselves from the value judgments of Critique. Though my primary intention is to do justice to Megerle’s work. In so doing, however, I’m also trying to counter the waning influence of symbolic value in certain segments of the art market.

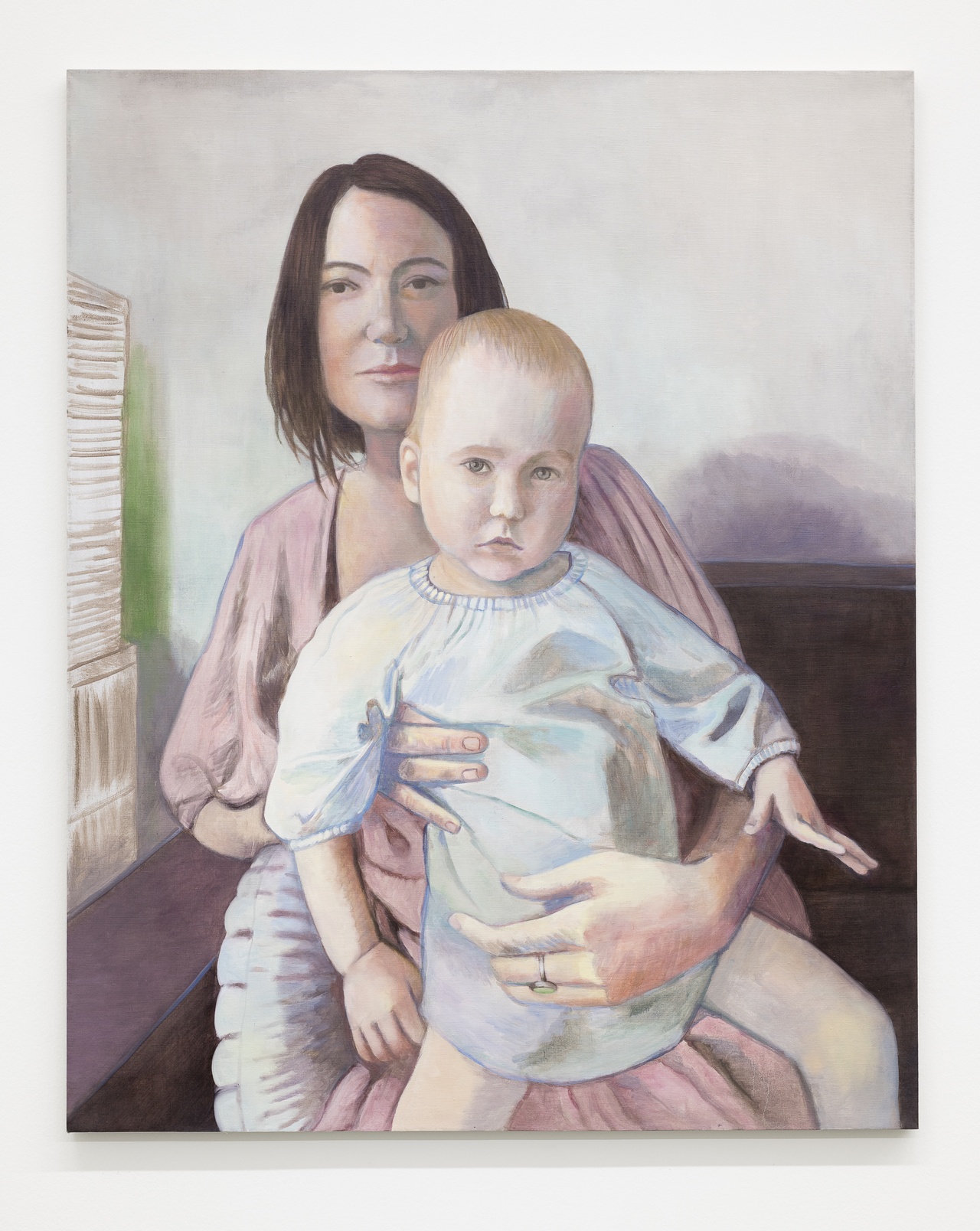

But first things first. Let’s take the portrait Interrelation as an example for my hypothesis that Melanie Klein’s thoughts on “object relations” echo in Megerle’s work. The picture shows a dark-haired woman in a dusky-pink dress holding in her lap a blond toddler who exhibits an aura of omnipotence. The child forcefully pushes himself to the fore and, it seems, resolutely away from his mother. Instead of depicting the mother–child relation in the tradition of Raphael as pure intimacy and symbiosis, Megerle accentuates the ambivalent and aggressive aspects of the relationship between infant and caretaker that Klein consistently emphasized. Far from merging with his mother, the toddler breaks away from her, most basically by dint of his rather monstrous size. Megerle’s portraits demonstrate throughout that subjects constitute themselves in – that they do not exist outside – complex relationships: in Kleinian terms, the framework of “object relations” that inevitably involve negative feelings as well. Consider the Alain Delon figure in Care IV, hugging the “little brother” in a gesture blending protection and paternalism inspired by a scene in Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers, or the young woman in a trench coat (Caprice) acknowledging with a knowing smile the presence of others who do not necessarily mean well: Megerle’s subjects are always enmeshed in complex and conflict-laden relationships. Subjecthood, in her work, is premised on an ambivalent sociality – just as it is according to Klein.

Birgit Megerle, „Interrelation“, 2023

It fits that Megerle pays at least as much painterly attention to her sitters’ outfits as to their relationship dynamics. The painstakingly rendered folds, fabrics, and textures – take the light-blue romper suit of the infant in Interrelation – leave no doubt that apparel plays a central part in her work. From Delon’s ribbed sweater in Care IV to the loose cable-knit pullover and glossy trench coat of the young lady in Caprice: clothes, for Megerle, constitute an abstract painterly zone. Yet unlike the classic fashion-maven artists, 19th-century painters like Édouard Manet or Berthe Morisot, she doesn’t primarily use garments to demonstrate her expert technical skill. Rather, they read as an index of their time (Delon’s sweater is very 1960s). The sepia tones, too, remind one of the photographic sources behind the portraits. At the same time, the apparel has gotten a fashionable update. There’s no doubt about its contemporaneity. History and presence blend into each other.

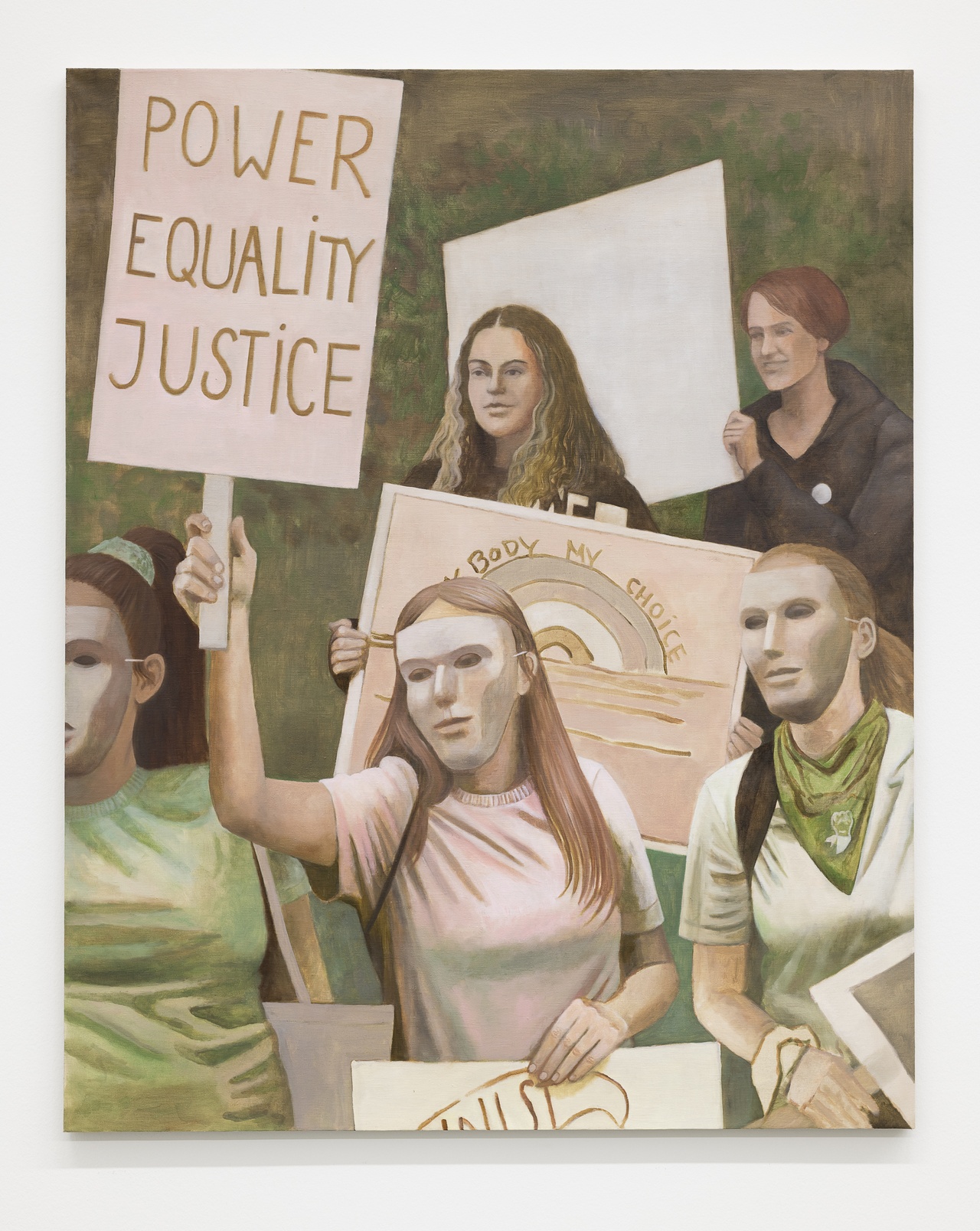

As noted above, Megerle installed three walls painted in light beiges and grays in the room to add hanging space. Their staggered placement in the gallery meant that the visitor entering the room didn’t have an unobstructed view of the paintings. So I made my way to the pictures past these partly empty surfaces, which reminded me of primed canvases. The walls struck me as symbolic of Megerle’s figurative visual language, which always supplies its antipode – the blank abstract pictorial surface. Each of the portraits features a backdrop that may be read as an abstract zone or a landscape. In Midi, for example – a veiled self-portrait – the background is based on the motif of a Cubist-style forest with dense foliage. The canvas-like temporary walls also pick up on the painterly trope of the “picture within the picture,” which features in Megerle’s central painting Signs (2023): a protest picture in pastels showing demonstrators, some of them masked, rallying against the US Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade and in support of the right to abortion. The ghostly figures hold up banners with messages such as “MY BODY MY CHOICE” or “POWER EQUALITY JUSTICE” as well as a blank one without any text. The mute sign – an abstract picture within the picture – is, I would argue, the prototype of the painted walls. The impression is that blank surfaces, in analogy with the muted colors, gently dull the noise of the textual messages in Signs, and the loud figurative pictorial language more generally.

Birgit Megerle, „Signs“, 2023

By transposing slogans like “Power Equality Justice” into the gallery space, Signs also makes the art world’s challenges tangible: the latter is a milieu that, as we all know, is decidedly short on both equality and justice. Yet the picture articulates its protest in delicate pastel hues (light pink, light green), signaling that any such remonstrance is subject to the conditions of painting. It was surely not by coincidence that the mother-and-child picture Interrelation mentioned above hung diagonally across from Signs. The proximity underscored that it’s perfectly possible to be interested in the psychodynamics of the mother/caretaker–child relationship while also being a staunch defender of abortion rights. What might seem like a contradiction is here visibly part of the same stance.

Midi, Megerle’s veiled self-portrait, comes in muted colors as well. We see a figure in a light-pink cardigan and a pastel-purplish hat who is glancing at us from the corners of her eyes. The peculiarly “dry” appeal of this oblique perspective bears an aesthetic resemblance to the portraits of Philipp Otto Runge. Yet although the figure unmistakably looks a bit like Megerle herself, she can also be read as alluding to earlier works by the artist, such as the portrait of the actress Françoise Dorléac, who, in a scene in Jacques Demy’s film Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967), has her portrait painted while sitting at the piano, an even broader-brimmed hat on her head. By short-circuiting her quasi-self-portrait with earlier portraits by her hand, Megerle appears to confirm the bon mot, attributed to Leonardo, that all painters au fond paint themselves. Unlike the Dorléac portrait, however, Megerle’s doppelganger sports the soft knowing smile we have already encountered in Caprice: as though the figures were thinking about their counterparts and about themselves at the same time. Moreover, the motif of the melancholy double demonstrates yet again that our self is made up of others, and that our dependence on others can be a source of joy, but also of sorrow – see Judith Butler’s The Force of Nonviolence (2020).

Painting aficionados flocked to Megerle’s show. Her institutional success was already evident in the enthusiasm of many museum people. Friends and acquaintances, too, praised Megerle’s portraits as her best to date. I wonder why their justified enthusiasm is not directly reflected in purchases by blue chip-collectors, the way it often did in the 1990s. I don’t think the only thing that has changed since then is that the connoisseur-collector type has been superseded by the speculative collector, who is primarily interested in rapid appreciation and cares little for the symbolic dimension. Moreover, it seems as if the desires of many collectors are now governed by laws of their own that are no longer in communication with criticism’s attributions of value. However, I firmly believe that the painterly and theoretical-psychoanalytical wager of Megerle’s intelligent portraits will pay off in the long run. If I didn’t, I would probably turn my attention other objects: as an art critic, I’m not prepared to say goodbye altogether to the idea that I exert some influence in the market. My objective in this review was accordingly to make the case for other values than those that prevail today in parts of the commercial sphere. Yet it’s impossible to predict with certainty at what point in time that symbolic value will translate into market value. And the latter, when manifesting itself in the continuous commercial success during an artist’s lifetime, is a double-edged sword. Just think of all the economically extremely successful artists who suddenly feel vindicated and produce work that more than anything else attests to their newfound sense of their own importance. Then again, it’s possible to achieve commercial success yet remain self-critical: many artists are quite conscious of the arbitrary nature of their achievement in a market that, in the final analysis, is always a bit of a crapshoot. That said, as a critic I remain structurally entangled in the market dynamics, even if my influence in some of its segments – such as the auction circuit – is vanishingly small. Right now, though, the winds seem to be shifting once again, as some speculative collectors have pulled out of the art market due to high interest rates. They prefer to put their money to work in their bank accounts. This development suggests that criticism’s finest hour may have arrived, and reviews like this one might regain a bit of their former influence.

“Birgit Megerle: Bond,” Galerie Neu, Berlin, March 10–April 15, 2023.

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and Vom Nutzen der Freundschaft (Spector Books, 2022).

Image credit: © Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Neu, Berlin; photos Stefan Korte

Notes

| [1] | Editor's Note: This is a revision of the review initially published on September 20, 2023. |