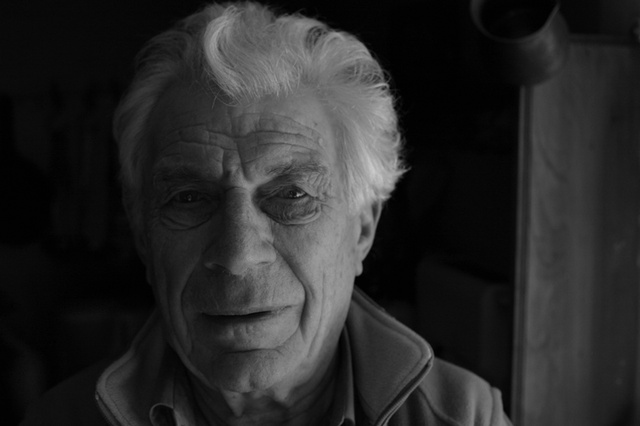

Svetlana Alpers on John Berger (1926–2017)

At first glance, “Portraits: John Berger on Artists” (2015) appears a formidable book. It is very thick. The binding is so tightly stitched that it is hard to hold open. The spare illustrations are all in black-and-white. As the author says in a brief preface, they are not items in a luxury brochure for millionaires but simple memoranda. But reading it is a confirming or, perhaps better, a liberating experience. Tom Overton, the cataloger of those of Berger’s papers recently donated to the British Library, has assembled a history of art out of the author’s changing viewings and views of individual artists. It brings us back to making and looking at art as an essential human enterprise. Given the state of the world, this is a moment to reread John Berger (b. 1926 and, until very shortly before his death this past January, still very much alive and still writing).

He dropped out of art school after WWII because he decided that rather than pinning paintings to a wall there were too many political urgencies to attend to. In 1962 he left England for good, finally settling in a French alpine peasant village. But art, whether making drawings or photographs or writing, has always been a center of his broadly Marxist production – from novels to essays to reviews to the famous 1972 TV program “Ways of Seeing” and the marvelous “Success and Failure of Picasso” of 1965.

Let me try to give a taste of it: take the Fayum Portraits – those remarkably present Greek -inspired Egyptian frontal paintings of the faces of the newly dead. Portraits about the experience of being looked at, Berger writes. We were not meant to be seeing them. They were meant to be buried with the dead. But Berger also sees them in our time, when the media surround us with an unprecedented number of images, many of them faces. Is that impersonal noise a way to be alive? For us, in the midst of that, these portraits can be life-affirming. And also (this is a characteristic Berger move), we are seeing them in a century of emigration: “So they gaze on us like the missing of our own century.”

Berger is a historical writer. History situates the artist at the time of making, but it also belongs to the living viewers when they see things made in time past. Viewing is a happening that never stops.

The Fayum portraits are immediately followed in the book by Piero della Francesca, presented here as the supreme painter of knowledge, of a state of mind. He is painting what the world would be if we could fully explain it. Unlike later painters, Piero hid nothing. A mathematician, he was close to science. We need, Berger suggests, that confidence in bridging art and science today.

Or take Géricault’s small paintings of mad people. I remember his extraordinary head of an old woman, now in the museum in Lyon. Berger relates them to historical attitudes toward madness – from being a rarity (as it was to Géricault), to being something one could hope to cure, to being, as Berger understands it today, typical of human life. He places our view of Géricault by describing the huge gap between the normal experience of life on this planet and the public narratives offered to give sense to that life. His mad man seems, to Berger, a consequence, not a rarity. Are we even able to feel compassion today?

Or a marvelous passage praising a Van Gogh drawing of olive trees: “[…] everything he sees he fingers […] within the drawing today there seems to be what I have to call a gratitude which is hard to name. Is it the place’s, his, or ours?”

Berger sticks to the historical realities of every maker, the realities of the studio one might say. But he also writes of seeing historical art in his own time – a time whose circumstances, in his view, are grim. No idealist, Berger accepts the fact that looking changes with the times. Take his views on the English painter Francis Bacon. Berger started out 60 years ago writing about him negatively – the horror in his work was fashionable, not real. But a little more than a decade ago he changed his mind; it seems the pitiless world that Bacon invented turned out indeed to be the way of the world in which we live. The work was prophetic.

Berger values – more properly put, loves – art to the full. That means he takes it seriously as a register and measure of the human condition. Who else these days writes about art in this way for a large public?

Last October (2015), I had dinner with John Berger and his companion in their house in a Paris banlieue. At one point, I ventured to say that I thought I wrote to get things clear in my own mind. NO, John said, as he lifted his huge chest upwards at table, I write to make things clear to the world (or did he say to intervene in the world?). True enough. But reading this book, I believe he also writes to get things straight. Maybe I write more in the spirit of intervening than I admit?

This text, which appears in English in the March 2017 print issue of Texte zur Kunst (#105) was first published online as: Svetlana Alpers, “Life of the Mind,” by Phi Beta Kappa’s Key Reporter, http://www.keyreporter.org/BookReviews/LifeOfTheMind/Details/1898.html.

Notes

| [1] | Sandro Klopp, „Seasons in Quincy. Four Portraits of John Berger“, 2016, Filmstil |