Miranda Warning Amanda Schmitt on the Power of Allegory and Allusion

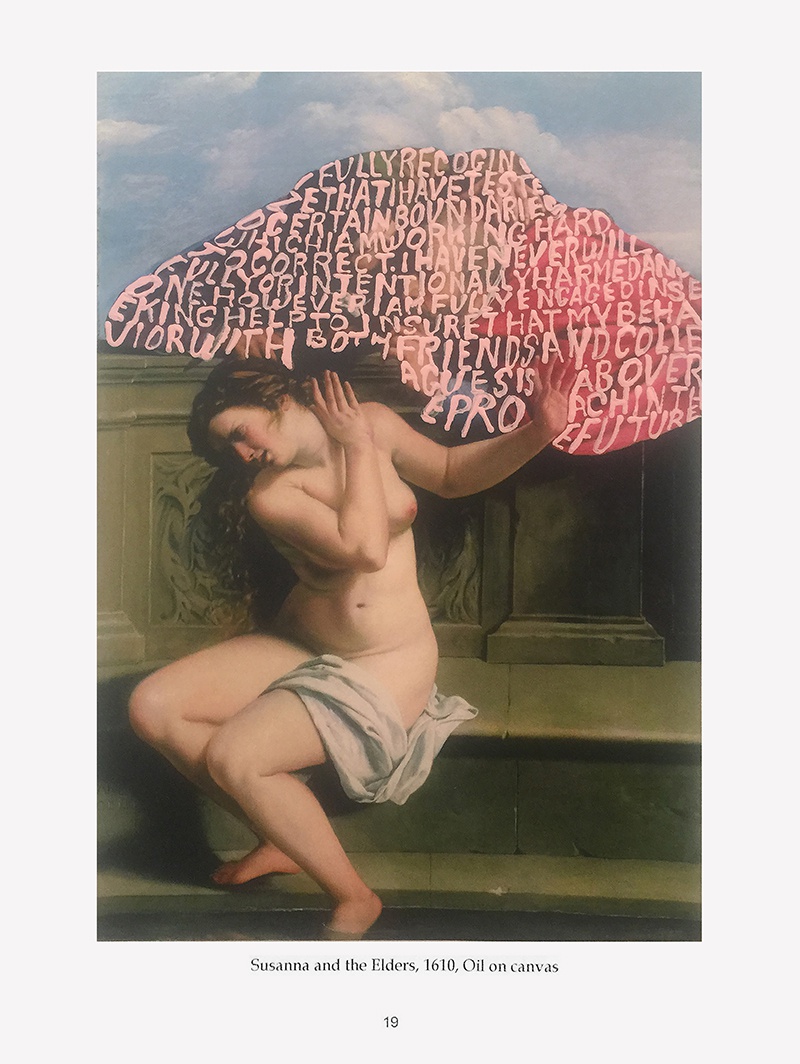

In 1610, a young painter at the beginning of her career named Artemisia Gentileschi depicted the biblical story, Susanna and the Elders. Four centuries later, in early 2018, the artist Betty Tompkins tore a reproduction of this painting from an art history book to create a work for her Apologia series. The story of Susanna, like Artemisia’s, like Betty’s, and like mine —and like so many others— was that of a young woman subjected to lecherous and abusive behavior by men in positions of power.

As a version of the story goes, Susanna sets out to bathe. In her private moment of wholesome pleasure, she is taken advantage of by two peeping perverts (the “Elders”). Knowing that they had violated her privacy in their lewd voyeurism, they fabricate a salacious lie about Susanna and blackmail her, using this threat to demand she have sex with them. When Susanna refuses, the men retaliate and throw Susanna to the courts to be sentenced to death, accused of a falsified crime. The story ends with Susanna’s virtuous triumph: it is the Elders who are put to death. Susanna regains her integrity, but not without her life threatened and significant damage to her reputation.

This is just a story, one which has been selected by both Gentileschi and Tompkins, perhaps because it stands as a vivid collective allegory for abuses of power and sexual violence. This image is especially powerful today in light of the recent allegations of sexual misconduct and complicity emerging from those who wield tremendous influence in the art world (not to mention countless other industries). Although these abuses have been broadcast publicly in the recent months, we are reminded that--in the words of the late art historian Linda Nochlin--“If we turn from allegory to historical reality, we find that women have, for the most part, had a hard time of it…in all realms of high art.” [1]

Gentileschi’s choice of allegory turned out to be prescient, for the parallels between her painting and sympathy for Susanna would become all too real: a year later, Gentileschi was raped by an elder male painter (who was in her home, meant to be teaching her), whom she subsequently indicted. Initially disbelieved, Gentileschi was put on trial, her horrifying trauma exposed to the public to be analyzed and scrutinized in invasive detail. [2]

Although Gentileschi was an unquestionably skilled and accomplished painter, something of her legacy as an artist is overshadowed by not only this crime against her body, but also by the conduct of the prosecution and the trial that was held to address the crime. The court did not initially believe Gentileschi’s testimony. Instead, she was subjected to a gynecological exam in the court, in front of the judge, to prove that her body had indeed been penetrated. Further still, she was then forced to submit to the tortuous process of the sibille, an instrument which slowly crushed a plaintiff’s fingers in order to pressure them into confessing the truth (in Artemisia’s case, to determine whether or not her virginity was forcibly taken by her accused, the painter Agostino Tassi).

Gentileschi was contemporaneously recognized, yes, for her work as a painter, but her legacy is also defined by her status as a woman who not only had the courage to report sexual misconduct, but sought justice for it as well. As her career progressed she grew to be celebrated, but her artistic merit was never recognized in the way she believed she deserved: in her own words, “If I were a man, I can’t imagine it would have turned out this way.” [3] Worse perhaps is that contemporary mass media interpret some of her best work, such as Judith and her Maidservant (1613-14) and Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614-20) —other biblical stories whose subject matter was highly popular at the time with painters—as “revenge paintings.” [4] As if her entire subsequent career proceeded as a personal vendetta, an attempt to regain her dignity and to assert her female power.

Although I am not a painter, I am a woman in the arts. I wonder if my career will be defined by my lawsuit, Amanda Schmitt v. Artforum International Magazine, Inc., and Knight Landesman. Or more importantly, could this moment, for women in the arts, be defined by (again, in the words of Nochlin) a staunch refusal of their “time-honored role as victims [of men]”? [5] Can this moment be used to define a new legacy, and more crucially, to instate a new trajectory for women in the arts?

Like Gentileschi, I was harassed and taken advantage of at the beginning of my career. Tassi, to justify his crime, offered marriage (albeit, as a feeble attempt to restore patriarchal honor to Artemisia’s father, Orazio). Knight Landesman offered "career advice." Artforum offered a "female task force," as a way to publicly address their undermining failure to uphold their "feminist ideals." [6] (It was rebuffed in a public letter signed by more than nine thousand women in the arts: “We will not join ‘task forces’ to solve a problem that is perpetrated upon us.”)

Just like Artemisa Gentileschi, I seek accountability. I seek recognition of the abuses of power and acknowledgment of hypocrisy, to call the problem by its name and to establish the groundwork for lasting structural change.

In her current retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Zoe Leonard envisions what lasting change might look like by utilizing the museum, as a public and private forum, to pay homage to the great query posed by Nochlin in 1971:

"Those who have privileges inevitably hold on to them, and hold tight, no matter how marginal the advantage involved, until compelled to bow to superior power of one sort or another.

Thus the question of women's equality--in art as in any other realm--devolves not upon the relative benevolence or ill-will of individual men, nor the self-confidence or abjectness of individual women, but rather on the very nature of our institutional structures themselves and the view of reality which they impose on the human beings who are part of them.”

These words, along with other excerpts of the formative essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, are posted throughout the administrative offices of the museum. It is crucial to note that the boundaries between the public spaces of the museum (for visitors and art-viewing) and the private offices (for employees and administration) are made visible, through glass walls. Thus, the symbolic intent in Leonard’s placement and curatorial collaboration (between the artist and Elisabeth Sherman, Bennett Simpson, and Rebecca Matalon), aided by the vision of the architect Renzo Piano here is clear: institutional transparency.

Betty Tompkins is working to record this moment into art history, through her Apologia series. As powerful male figures in the art world attempt to publicly issue apologies for their misconduct, or admit loss of ‘privileges,’ Tompkins cements these words for further internal circulation and in so doing reveals ‘institutional and intellectual weaknesses’ [7] throughout our industry and its built-in complicit and enabling system of historical inscription.

In my contemporary viewing of it, Gentileschi’s Susanna seems to convey some level of exasperation in her face, an annoyance, maybe. It reminds me of an expression that was repeated in some of the more popular signs (held by many of our elders) at last year’s Women’s Marches across the world.

Zoe Leonard, “Homage” (2018), installation view, 2018

Zoe Leonard, “Homage” (2018), installation view, 2018

Protest comes in many forms and it is a continuous project. Art can break rules and open doors that appear to be permanently closed. Artists like Betty Tompkins, Zoe Leonard, and Artemisa Gentileschi —among countless others (to whom, in their private and public acts of solidarity, I remain grateful)— clarify, expose, and articulate issues which many still find unspeakable. In Gentileschi’s depiction of Susanna, Tompkins and I have found a warning, imaged centuries ago, that this road is a long one, and it’s not going to be easy, but that each of us has the responsibility of paving the way for those to come. By pursuing prosecution (and in Tompkins’ and her gallery’s case, by inserting this dialogue into the marketplace), both Susanna and Gentileschi forced their communities to take a position, and in so doing, dismantled the false consciousness of complicit neutrality.

I am writing this about Artemisia and Betty, and Zoe and Linda, not only as an act of identification, gratitude, and historical solidarity, but also because my lawyers cautioned me not to write anything about my own experience at this time. This is another kind of silencing, though its juridical forms of suppression mirror those of Gentileschi’s time as well. In contemporary parlance, we all know that “Everything you say can and will be used against you in the court of law.”

Since allusion is all that I am safely allowed, I turn in the end to the words of another witness, Margaret Atwood, whose secret code from The Handmaid’s Tale reads: Nolite te bastardes carborundorum.

Amanda Schmitt

Title image: Betty Tompkins, “Apologia (Artemisia Gentileschi #4)”, 2018

Notes

| [1] | Linda Nochlin, “Women Artists Then and Now: Painting, Sculpture, and the Image of the Self.” Global Femi-nisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art, 2007. |

| [2] | The case was fought in 1612 in Roman court, and the full transcript has been preserved and translated to English and published in Mary D. Garrad’s monograph on the life and work of the artist, "Artemisia Gentileschi - The Image of The Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art" (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989). |

| [3] | Keith Christiansen and Judith Walker Mann, Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi, exhibition catalog. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013. |

| [4] | The Guardian has in recent years described Gentileschi as “More Savage Than Caravaggio,” and the media conglomerate VICE has broadcast that she “Specialized in Revenge Fantasy.” |

| [5] | Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader. Ed. Maura Reilly (New York & London: Thames & Hudson, 2015). |

| [6] | Public Statement issued by Artforum, October 25, 2017, Artforum.com. https://www.artforum.com/news/id=71891 |

| [7] | Linda Nochlin, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" (1971), in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (Boulder: Westview Press,1988), 147-158. |