STATE OF PLAY Stephanie LaCava on a Season of Stage Art and Durational Drama in New York

Diamond Stingily, “Past,” 2023, detail

Turn of the year and Manhattan is its own Atlantis, an island holding her breath. Spiritually dissolving, she’s unsure about what she can lose. An unseen net traps data and capital flow, quick and connected. Technology escalated fast; creeping technocracy. Still, New York remains aloof. She toys more than usual with intimate-scale theater and poetry; sees a stage set showing up as an art exhibition; actors as objects. Then, a clever twist: a short film plays on loop, every viewer written into the script, a bumbling spectator as lead character. The twisted city laughs as she live-casts the gallery-goer.

Even in 1969, during a visit to New York, Pier Paolo Pasolini was able to see the beginning of this troubling atmosphere, this confused city: “A much more complicated world, with an undercurrent of mass culture still undefinable and menacing.” After falling ill and finding himself unable to work, Pasolini picked up a pen to write six tragedies in verse. This possession ceded to magical expulsion, as he tells it. Theater freed him – cured him – “through a decision to do something that by its nature, by definition, could never become a mass medium. And in fact theater isn’t reproducible.” A play escapes spectacle because its audience is still “a flesh and blood public … of individually identifiable people, in front of flesh and blood actors.” [1]

New York coughs dramatically as if she’s about vomit. She’s not ready to fall sick. She spits up.

In the past few months, there has been a palpable increase in interest in both the staging and viewing of lo-fi theater or IRL gigs like Ruby McCollister’s Tragedy, or the Adult Film troupe’s Last Night Was a Play and Coastal Elites. A more stealth nod: Soho Boys at Secret Pour playing music with a painting on the wall of the infamous Ikea monkey meme, “When we were poets” written below it in Helvetica.

These are only sparks, hits off the consistent excellence of stalwarts like the Wooster Group or Richard Maxwell and the New York City Players. The former recently previewed Symphony of Rats, a new production based on Richard Foreman’s 1988 Ontological-Hysteric Theater play of the same name. It tells the story of a Nixonian figure, a president descending into madness. These sort of preview performances, similar to readings, are events with singular audience energies. Texts can be worked out in real time, logged post-factum on the page. The inverse happens, too: the spectators feed off the players’ antics to negotiate their own realities. As one of Foreman’s characters says, “It’s time to relieve yourself of the belief systems you only partially believe in.” Richard Maxwell is working on another story about shifting hierarchies. His is the yet-untitled narrative of the only daughter of an Irish American family who has just lost its patriarch. A vacant building downtown is being explored as the venue for the staging of the play, New York real estate gone awry, transformed into an unlikely gate of imaginative redemption.

Meanwhile there’s Pulitzer Prize–winner Annie Baker’s Covid-delayed Infinite Life about five women at a health clinic, played to acclaim at Atlantic; John Turturro in an adaptation of Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, cowritten with Ariel Levy; and Michael Shannon (aka DC Comics villain General Zod) as Estragon and Paul Sparks as Vladimir in Waiting for Godot at Brooklyn’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center. Beckett’s estate mandates that his plays are brought to stage without adaptation. This doesn’t account for what could happen IRL. A breathing, sighing, laughing audience is an enemy of (the Beckett) police.

Elsewhere the set piece channels unsettling theatrics. Diamond Stingily – who appeared in fellow artist Martine Syms’s film The African Desperate (2022) as a sculptor having a crisis as she finishes art school – opens the solo show “Sand” on the ground-floor gallery at Greene Naftali. Inside four pens of sand, one at the end of a constructed long jump runway, are hidden bronze-cast body parts including fingers and feet. It is difficult not to think of Edward Albee’s 1959 absurdist play The Sandbox, about the degenerative values of an American family who neglects their grandmother’s care. In the second part of the show, Stingily sections off the back room with a padlocked gate, similar to those seen in her previous works. A draped mauve valance hangs in the center of the back wall, like a stage curtain, with two freestanding lamps, one on either side. In the middle is a small photograph of a funeral home in Chicago where many of the artist’s family members had their services.

Currently on display at the MoMA is another of Stingily’s set-like works, Entryways (2021). There are three hinged doors with different baseball bats leaning at their sides. Stingily has said this came from her memory of her grandmother’s own front door. Rindon Johnson writes that the first time he saw Stingily’s recent work “I thought of Anton Chekhov’s gun: ‘if in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.’” [2]

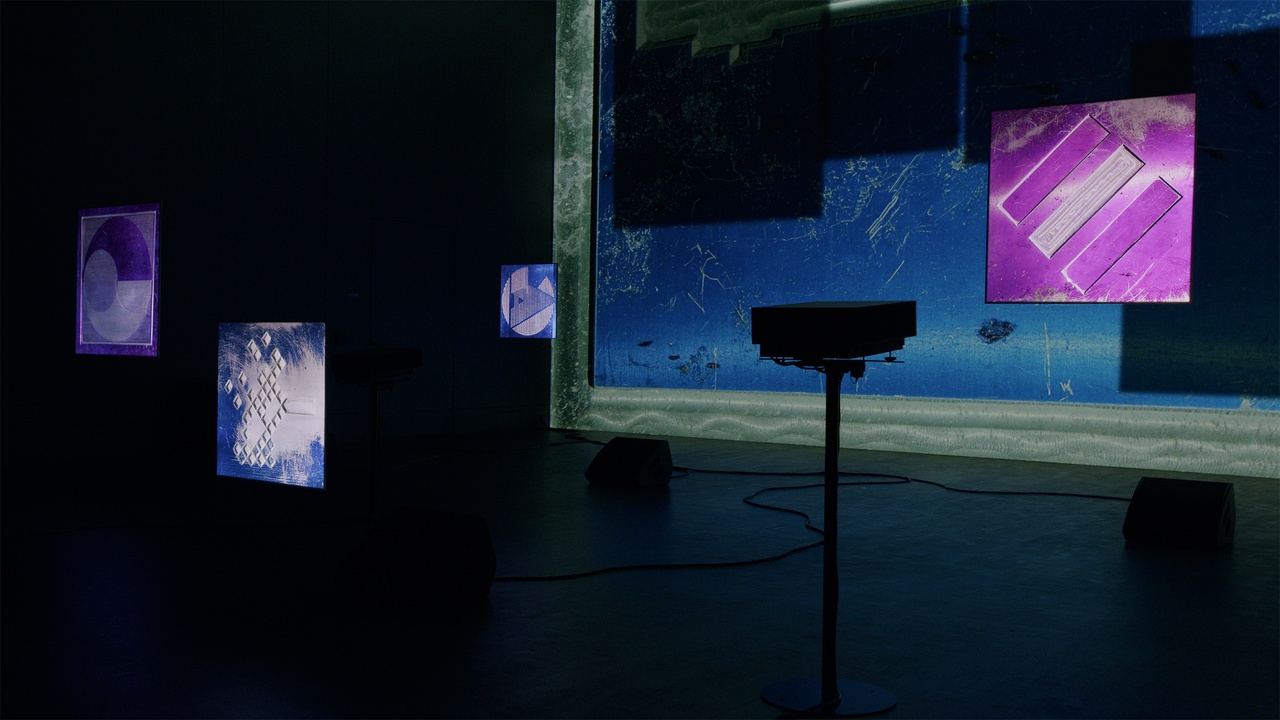

“Alexandre Estrela: Flat Bells,” Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, 2023, installation view

Nearby at MoMA is Flat Bells (2023), an installation by the Portuguese artist Alexandre Estrela in the fourth floor Studio. Metal plates modeled on 1980s logo printing plates are used algorithmically to generate shifting sound and color. “The sound and image you’re experiencing are neither celestial nor supernatural but the echoes of the extraordinary existence of an artificial organism,” writes Estrela in a leaflet text. However, he cautions, “bear in mind that the bells’ behavior is colored by volatile humor.” The day I see the show alongside its curator, there is a glitch in the system – a laugh, perhaps. While the work is generated live and meant to be unpredictable, its imaging behavior that day was something she hadn’t seen before. She explains to me that, strangely, though visitors are allowed to move between the objects on the floor, they generally decide to sit facing the main projection. Typically, the back wall of the space is floor to ceiling windows onto a Manhattan cityscape, but Estrela insisted here on a drywall intervention.

The work becomes its own kind of durational theater. Visitors lend their time to this room, clocking longer engagement than in front of other works in the museum. The room is thereby seemingly “played,” onlookers both player and audience. Estrela’s text continues, “the hazards of coexistence generate a complex code of musically inclined signs, which can be understood as a new visual language or as a post-dodecaphonic, post-minimal, post-concrete form of music.” Even the old signs have grown weary.

New Theater Hollywood

Downtown, on the Lower East Side, “Signs of Wear” at Reena Spaulings features photographs of damage by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff. Episode 1 of their work-in-progress film series plays nearby telling the story of a character who comes into money as compensation for being hit by a bus. These funds are then used to purchase a theater, not unlike the one the artists will open in Los Angeles this coming weekend, on January 14th. The short movie plays on a screen standing on a counter found backstage in the same spot on Santa Monica Boulevard where Henkel and Pitegoff will run New Theater Hollywood. They plan to keep the space open for two years, harnessing the surrounding energy and channeling it into alternative performance.

New York is not yet Atlantis, but the swell is hungry to capsize greedy empire. “Make work that is more abrasive, more complicated, and also more provocative, perhaps to render it as little consumable as possible,” Pasolini advised in his early warning: make things that can’t be swallowed whole.

Stephanie LaCava is a novelist and critic. Her first novel, The Superrationals, was published by Semiotext(e) in 2020, while her second, I Fear My Pain Interests You, came out from Verso in 2022. She lives in New York City.

Image credit: 1. © Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, photo Zeshan Ahmed; 2. © Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, photo Oresti Tsonopoulos; 3. © New Theater Hollywood, Los Angeles, photo Calla Henkel