No Meaningful Loss, Tal Sterngast on Joav BarEl at Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv

Joav BarEl, Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv, 2012, exhibition view

Works of art that seem contemporary yet have been produced in another era are like phantoms. They are here but live in another dimension. It is hard to find the right tone to speak about them, to categorize them properly or speak of relevancy, because they rather reflect our contemporary regime of spectating, in which relations of time and distance are being eliminated and unified, than raise questions about what the works are. They are, in a way, appropriated, rejuvenated, displayed, and framed by the exhibition.

The exhibition “Pop Works” at the Tempo Rubato gallery in Tel Aviv gathered eleven acrylic paintings by Israeli painter Joav BarEl (1933-1977), all made around 1969. The beaming, pictorial paintings share a reduced spectrum of phosphoric, complementary colors. At times, they appear like shimmering collages, made from negative/positive patterns. The somewhat threadbare canvas edges can be noticed only at a closer look and bring up the paintings ’age‘ and provenance.

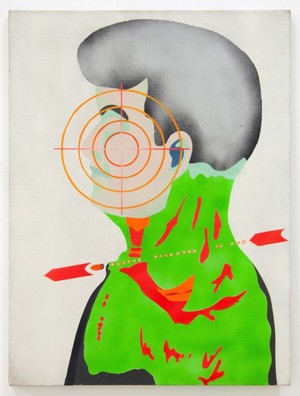

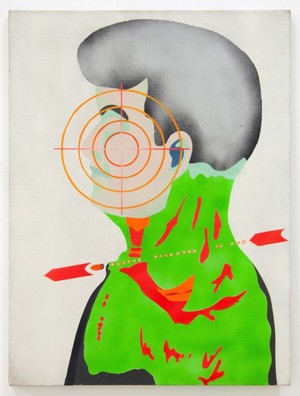

Joav BarEl, “Kennedy Assassination”, 1969

A schematic profile of a man’s face is seen through circles of a target diagram in “Kennedy Assassination”. A grey-sprayed, Elvis-like forelock frames the face; a neon green area shapes the figure’s body, spotted with glowing red and orange stains that evoke blood splatter or a cross section of inner body parts. An illustration of a bullet’s straight movement ‘through’ the figure is painted in a diagonal dotted line, piercing the body and cutting through its assumed trachea. The diagram of the bullet’s route through J.F. Kennedy’s flesh, striking him in the back and exiting through his throat, was by 1969 (when the work was made) already a subject of several US federal investigations and at the heart of what was to become one of the most mysteriously unsolved controversies of the 20th century, namely: who conspired to kill the popular American president? While the hairline cross in BarEl’s painting might relate to Jasper Johns’ “Target” paintings (from mid 1950s onwards), most likely, Andy Warhol’s “16 Jackies” from 1964 – a grid of four photos of Jacqueline Kennedy selected from the massive media coverage of Kennedy’s death and its aftermath – had made an impact. BarEl used the deceased president’s figure as a media icon as well as the well-known diagram that was, (along with amateur 8mm film footage) at the center of the famous “Magic Bullet Theory”.

Engaging in political and cultural life in America, at that time New York (still) being the definite center of the contemporary art world, Joav BarEl showed a desire to reach beyond this peripheral art economy of Israel in the late 1960s. His use of industrial spray and complementary colors as well as negative/positive grids refer to photographic and print procedures. Spatial depth collapses in these late 1960s’ works into flatness of color; the ‘picture’ (rather than the painting) is held together by an image, which was already there, a ready-made image. Here, BarEl identified or experimented with first-generation Pop Art that had been just formulated ‘overseas’ against the imperatives of high abstract art. The work of artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Richard Hamilton who were introducing the commercial, the representational and mechanical reproduction into art, and were engaged with the American image industry in entertainment advertisement, served evidently as the form BarEl was attempting to ‘fill’.

Joav BarEl, Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv, 2012, exhibition view

Symbolically, BarEl died in 1977 at the age of 44 from a heart attack as he was stepping out of the airplane on his way to leave Israel to the USA. In Israel, BarEl was an artist, influential art critic, writer, lecturer, psychologist and co-founder of a locally significant artists group called 10+. The group collaborated to react-rebel, in a reduced, imported from abroad manner (Paris-London-New York), against the strictly modernistic artists (abstract art, painting-as-painting) who till then had inhabited the art establishment of the young Jewish state. The work of 10+ artists was already pervaded by the idea of the Readymade and concerns of the immediate-historical as well as by the political and material conditions of art production. BarEl’s own artistic work was eclectic, he made expressionist abstract reliefs of stone, epoxy and plaster, small works on paper like ink drawings and collages for Kafka’s novels, conceptual sculpture and installations (like “Dysfunctional Door”, 1971), and left behind a book with unrealized concepts (“Book of Ideas”, 1969-1974).

In his current exhibition in Tel Aviv, black and white stripes fill the painting “Ma’avar Hazaya (Crosswalk)” from top to bottom. Two graceful female model figures and a strange shadow of a moped driver inhabit it. The striped background serves as a flickering op art surface as well as an endless staircase on which the figures move, dressed in white, Chanel-like fashion outlines. (Jackie Kennedy's blood-splattered Chanel suit that she wore on the day of the assassination comes to mind ). The moped slices the space between the two women. They both turn their back to it and its driver: the woman in the background turns her head to look at him while the other one walks away; and in the mirrored parallelism of their movements their relationship seems to be temporal just as it could be spacial: a sequence of a ‘Before’ and ‘After’ event. The figures’ faces are sprayed: eyes, hair nose and lips are marked graphically as holes or stains, as though they were printed negatively.

Joav BarEl, Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv, 2012, exhibition view

“Coming?…” shows a female in a red dress with her hand frontally between her legs. The painting’s ground is a radiant green grid, divided by straight yellow lines into either a cross or possibly a dance pole. The woman’s face seems unfinished: it is drawn in pencil and the red lips are the only feature painted in the face. The white (unpainted) hand is placed elegantly on the woman’s lower part, giving the impression that she could be masturbating. The title “Coming?…” may be understood as liberated or as suppressing, as a vulgar joke or a cheeky demonstration. And just like the title, the hand gesture in the painting, at the focus of our view, is as liberated as it is suppressing, a sign of sexual revolution or a manifestation of an objectified female image with a weakened ‘gaze’? The woman sampled here, with eyes hollowed out like a skull, is glamorous yet cheap, comic and desperate. The ‘gaze’ as a vehicle of existential articulation of desire, but also of self-defense, is displaced into the woman’s red lips. This maneuver reoccurs also in “Models in Red and Green (‘Up Set’)” where the feminine lips condense articulation.

How is one to receive these images of female sexuality – the topic that applies to more than half of the paintings in the exhibition? Despite visual similarities, BarEl’s approach lacks the autonomy and female power of resistance which Pauline Boty’s pop works share with Evelyne Axell’s psychedelic, erotic air brush paintings on plastic and plexiglas showing female nudes. Both Women artists seemed to have embodied (through life and work) a certain optimism and liberation in pop and died young (Boty died at 28, several years prior to BarEl’s paintings, and her work had been almost forgotten for three decades until it was rediscovered 1990s; Axell died in 1972, at the age of 37) – just before Pop Art became preoccupied by market mechanisms. Several of BarEl’s paintings like “Woman in Red with White Hair”, “Models in Red and Green (‘Up Set’)” or “Coming ?…” are populated by real-life fashion models (BarEl worked with a slide projector) yet unlike Boty’s and Axell’s women, they are depicted by a man who expressed a lifestyle as masculine as could be, in the midst of a chauvinistic and militarist culture. Much more than an image of women’s changed self-perception in the 1960s BarEl’s figures rather serve as commodity fractions, as signs of a void that hides no promise of revelation, but also (in relation to and against the imperatives of the high abstract and the aura, in the old sense of the word) no meaningful loss.

Joav BarEl, Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv, 2012, September 5 – November 3, 2012