UNTANGLING SHADOWS Emile Rubino on Daniel De Paula at Galeria Jaqueline Martins, Brussels

“Daniel de Paula: veridical shadows, or the unfoldings of a deceptive physicality,” Jaqueline Martins Gallery, Brussels, 2021, installation view

Cables run throughout Daniel De Paula’s exhibition “veridical shadows, or the unfolding of a deceptive physicality.” These cables connect a freestanding LED multi-screen setup to some of its detached units positioned throughout the space at Galeria Jaqueline Martins’s new location in Brussels. The video playing on these monitors is a bewildering compilation of appropriated drone footage from the inspection of ballast water, oil, and gas tanks in cargo ships. In the description of this work, soberly titled obscuration (2021), the word “negotiation” implies that the process of obtaining the footage should be considered an inherent part of the piece. This expanded approach is not uncommon for De Paula – his research often materializes through strategies of acquisition, appropriation, and displacement of structures or materials from political, bureaucratic, and financial institutions.

At the center of the exhibition is an engraved copper plate that De Paula borrowed from the Centre Céramique in Maastricht, and which was used for production at the famous Dutch glass and porcelain factory Petrus Regout & Co. in 1865. Before the publication of Das Kapital (1867), Karl Marx apparently witnessed the terrible working conditions imposed by Petrus Regout in the factory while he was in Maastricht to visit his sister. For De Paula, the materiality of this copper plate, engraved with decorative patterns of tangled flowers, hides the reality imposed by the owner of the means of production. The artist puts what he considers to be the “shadow” of this object – the history and ideological subtext contained within its materiality – for sale via an official certificate narrating this history and confirming the ownership of the “shadow.” While this gesture comes across as rather didactic, it does ground the rest of De Paula’s work within a regime where a “shadow” is at once a substance and an indicator of time, labor, and value.

Daniel de Paula, “fetiche-feitiço,” 1865-ongoing

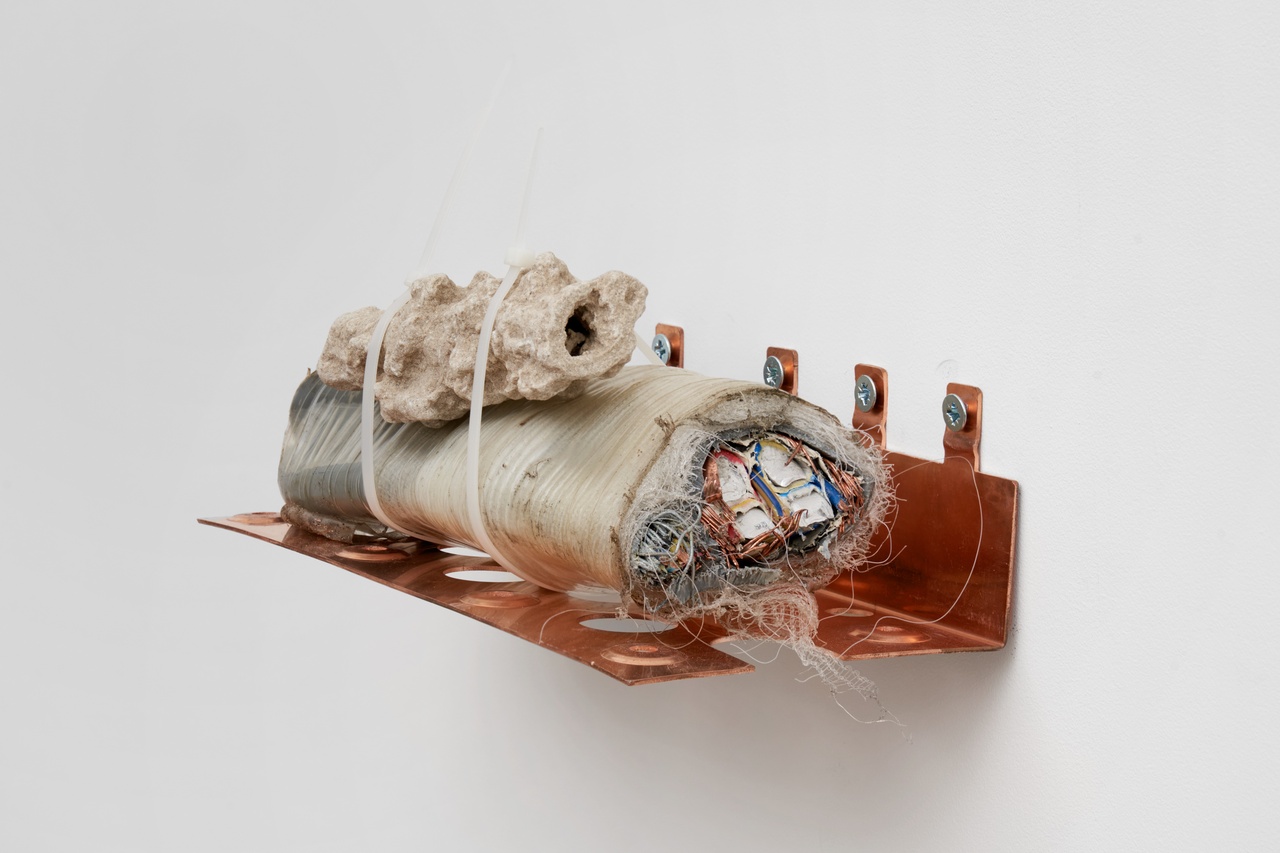

By addressing and uncovering the many layers of these material narratives and histories, De Paula also creates a framework for his conceptual research to take on a more physical form. Composed of small fulgurites zip-tied to cut-off sections of submarine and subterranean data cables, six sculptural arrangements titled power-flow (2020) make up a large part of the installation. Fulgurites are natural formations that occur when lightning strikes the ground and sinters various mineral grains or sediments together. In De Paula’s amorphous assemblages, these delicate mineral formations contrast with the heavy-duty cables. Despite the loose relationship to electricity that these two components share, the act of tying them together to compose these sculptures seems to result from a process of formal abstraction, more than from De Paula’s research. These constrained pairings appear to follow what Reza Negarestani would call a “protocol of cruelty,” whereby “abstraction is the order of the formal cruelty of thought. In its most trivial and unsophisticated form it involves pure mutilation: amputating form from the sensible matter. In its most complex – that is, most veritable – instances, it is the concurrent organization of matter by the force of thought, and the reorientation of thought by material forces.” [1]

Two of these odd contraptions are vertically mounted to the wall like prosthetic spines held by metal brackets from high-frequency antennas. On an opposite wall, a smaller cable assemblage presented horizontally on an L-shaped copper plate resembles an amputated limb – half a forearm, or a wrist with thick metallic bones and copper veins insulated by discrete layers of plasticky flesh. The visceral nature of this technological debris, which used to run at the bottom of the ocean, could call to mind Théodore Géricault’s gruesome still life Study of Feet and Hands (1918–19) – a preparatory work for the The Raft of the Medusa (1918–19). For this study, Géricault, not unlike De Paula, had to negotiate with people working in institutions in order to borrow fragments of decomposing corpses.

Daniel de Paula, “power-flow,” 2021

Submarine data cables, which have also been the subject of in-depth research and underwater photographs by artist Trevor Paglen, are exemplary of the dichotomy between dematerialization at large and our slow awakening to the tangible reality and finitude of digital means of production. After all, the sea of data and the sea where these cables run is also the sea where the bodies from The Raft of the Medusa disappeared and the sea where the bodies of migrants are disappearing today. In this regard, our ability to actually “see the sea” is even more limited than we may think. As Hito Steyerl points out, our “contemporary perception is machinic to a large degree. [And] the spectrum of human vision only covers a tiny part of it. Electric charges, radio waves, light pulses encoded by machines for machines are zipping by at slightly subluminal speed.” [2]

The invisible exchanges going through these cables and the forces that power them are often undermined by our old conceptions of digital means of communication as being different from traditional means of production or transportation. Already in the late 1970s, Raymond Williams identified the ideological blockage induced by the reducibility of means of social production to the realm of media, and to mere “devices for the passing of ‘information’ and messages between persons who either generally, or in terms of some specific act of production, are abstracted from the communication process as unproblematic ‘senders’ or ‘receivers.’” [3] Senders and receivers are no less unproblematic than the tools that connect them. In a previous exhibition at Galeria Jaqueline Martins in 2017, De Paula displayed a rock used as ballast in Portuguese vessels during transatlantic journeys to colonial Brazil. Stones like this one provided caravels with the stability that enabled the exploitative import-export relation and allowed aristocratic elites to accumulate surplus capital.

Daniel de Paula, “deceptive physicality, veridical shadows,” 2021

In the present exhibition, an inconspicuous plastic crate holds a small batch of decommissioned road reflectors equivalent to one kilometer on public highway purchased by the artist at auction from the Dutch government. Placed directly on the floor, social continuum reflection (2021) is reminiscent of Robert Smithson’s “nonsites” and their geometrical bins containing rocks. This work also elicits a tangible parallel with public transportation infrastructures by building upon De Paula’s 2015 site-specific installation testemunho. In testemunho, he displayed rock core samples resulting from geotechnical surveys performed for public works and mobility in the state of São Paulo in a way that formally emulated Walter De Maria’s The Broken Kilometer (1979) while directly addressing local issues of corruption linked to the construction of a nearby ring road.

Devising these connections between minimalist artistic legacies and societal concerns is a recurrent motif in De Paula’s approach to questioning the arduous relationship they maintain. In 2014, the artist also translated and made available to the public a manifesto written by Charlotte Posenenske in 1968, and treated it as a work, untitled [to Charlotte Posenenske]. Social continuum reflection is clearly informed by Posenenske’s thinking around dynamic structures and distribution networks, and it brings to mind her remark about the first major traffic distributor in the Federal Republic of Germany’s interstate highway system: “The Frankfurt junction is mine.” [4] This idea of artistically appropriating the commonly owned productive space represented by these routes and networks not only reiterates their social function but also highlights them as spaces where value creation occurs in unregulated ways in spite of the inherently public nature of these infrastructures.

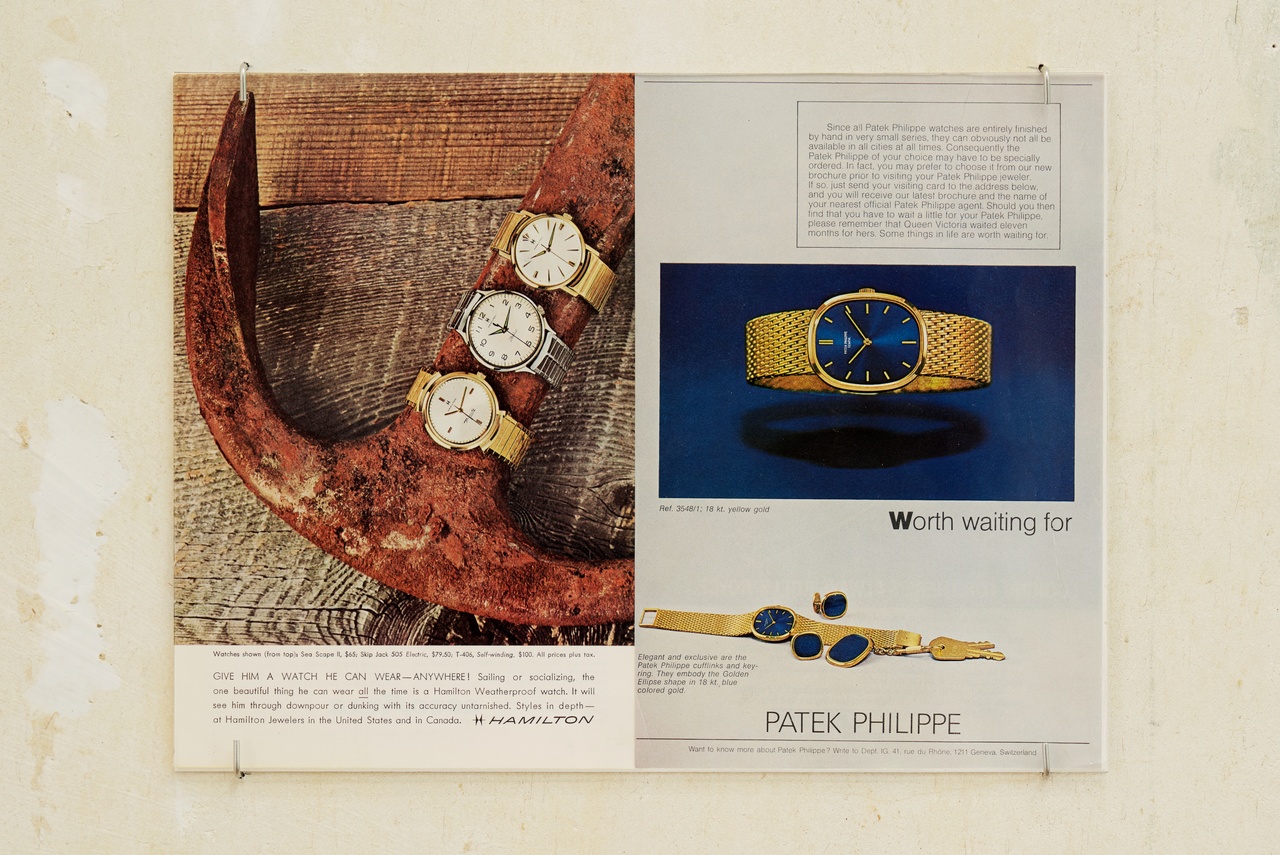

Like footnotes to the exhibition, a series of five collages of watch advertisements hang on the wall behind the gallery desk. Gold watches with precious quartz mechanisms look as if they are emerging from rocks and crystals; some are tied to a rusty pickax and accompanied by slogans such as “sailing or socializing, the one beautiful thing he can wear all the time.” Recombining abstract time, social relations, and materiality, De Paula’s collages, arrangements, and thoughtful displacements remind us that while “shadows” look as natural as the passing of time, they only exist because someone is casting them.

“Daniel De Paula: veridical shadows, or the unfolding of a deceptive physicality,” Galeria Jaqueline Martins, Brussels, June 5–July 31, 2021.

Emile Rubino is an artist and writer based in Brussels, Belgium.

Image credit: Galeria Jaqueline Martins, photos: GRAYSC

Notes

| [1] | Reza Negarestani, Torture Concrete, Jean-Luc Moulène and the Protocol of Abstraction (New York: Sequence Press, 2014), 5. |

| [2] | Hito Steyerl, “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition,” in Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (New York: Verso, 2019), 47. |

| [3] | Raymond Williams, Culture and Materialism: Selected Essays (New York: Verso, 2020), 57. |

| [4] | Burkhard Brunn, “Aspects of Her Work,” in Charlotte Posenenske 1930–1985, ed. Renate Wiehager (Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2009), 119. |