We Are the Revolution Isabelle Graw talks with Sarah Waterfeld (“Staub zu Glitzer”) and Anna-Sophie Friedmann (“B61-12”) about the Volksbühne occupation

Isabelle Graw: As I was watching (online) your first press conference during the Volksbühne occupation ((https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OQZHJv4O1g ), I was immediately taken by both the substance of your undertaking and its aesthetic specificity; how, for example, the lady playing the part of the press spokeswoman was styled according to the Volksbühne actress look; and how there was this rocket object set up next to her, which (though this was probably not your intention), I read as an allusion to Cosima von Bonin’s rockets. I also liked how you advocated for “getting off the hamster wheel.” It might be worth noting, of course, that getting off the hamster wheel, though a risky decision, often turns out in retrospect to have been a useful career move. In this, you also hit on the existential anxiety that’s increasingly felt among Berlin’s creative class as gentrification increasingly renders this city unaffordable, while at the same time demonstrating that a different kind of social space, a different kind of community, is possible – or in your words: “the reappropriation of the public space in the age of privatization.” Furthermore, you instituted a gender quota in your proposal, reserving 50% of positions for women. In light of the subtle forms of discrimination that women continue to confront in the cultural sector, that appears to indeed be a necessary measure.

All of this said, I do have a couple of questions concerning the art-theoretical premises of your project. The concept of “performance” is crucial to it: you’re very clear that what you’re doing is a “performance” rather than an “occupation.” That makes especially good sense in a theater, where everything is a production to begin with, a setting where actresses perform their parts and themselves. In an art context, however, one must also consider how performance is prized as the most advanced art form because it’s thought to be less compliant with the commodity form. This is a fallacy, of course, as the performer’s body is not incapable of becoming a commodity, a medium of value. The current desire for the live experience offered by performance art is surely also linked to the social media of our digital economy, which exploit our self-presentation as a resource. The program Chris Dercon has outlined for the Volksbühne likewise banks on performances, as when the event “Fou de Danse” in Tempelhof is billed as “All of Berlin performs itself,” or when the theater season at the Volksbühne opens with Tino Sehgal’s performance-based works. What’s ignored in this context is that the rise of performance as a coveted art form correlates with the growing significance of performance in the working world, where maximum performance (of self) is increasingly demanded. Given these factors, performance art seems to me to be a rather fraught art form. And so, then, why do you nonetheless invoke this tradition?

Sarah Waterfeld: We debated these questions extensively, and some in the collective preferred the idea of performance, while others disavowed it from the outset and referred to a “transmedia theatrical production.” I personally didn’t want the term “performance” in the press release, but not everyone in the collective uses the concept with scholarly precision. So it’s a word that was inserted with a non-specialist hand. Another factor was that “performance” was meant to convey a certain ironic overtone. When people approached us and said, aren’t you organizing the occupation, we retorted tongue-in-cheek that it was a performance.

Graw: The term “performance” also came up after the eviction …

Anna-Sophie Friedmann: I joined in only later — at the point when “Staub zu Glitzer” disbanded on day X and “B61-12” was launched – but have been intensely involved since. Although I have educated myself about what happened before I came in, I have a very different perspective arriving mid-stream, and so speak, here, only for myself. As an actress, I do think that “transmedia theatrical production” is the more accurate and precise term for what we’re doing. But I don’t see why “performance” would necessarily be that concept’s antagonist. All those wonderful intellectual ideas are helpful only when we can get them across to people. So when we speak a language everyone understands, I do not see a contradiction so long as the chosen word matches the substance. To my mind, both “performance” and “transmedia theatrical production” describe action art: art in the form of an action. Performance doesn’t strike me as an inappropriate term—it’s just less specific.

I personally prefer people to call us performers rather than occupiers, because the word gestures in the right direction; many people are unaware of the distinction between mimetic, performance, and transmedia theatrical productions. Still, it would’ve been more consistent to not mention the word “performance” at all. We should’ve kept calling it a “transmedia theatrical production” until people would’ve been forced to look it up.

Graw: Maybe this is a good opportunity for you to explain what you mean by “collective, transmedia, mimetic theatrical production.” In preparation for this conversation, I looked at the “Transmedia Manifest” (https://transmedia-manifest.com/), to which you’ve referred. It proposes that transmedia is about fiction superseding reality. That made me wonder whether, especially in the context of an occupation, it might not be more interesting to bring out the tension between reality and fiction. Doesn’t conflating the two mean giving up on the possibility of making a real difference, which is to say, engaging in politics?

Waterfeld: The goal isn’t to replace reality with fiction. Rather, it’s more about recognizing that fiction and reality play equally important parts in the making of our world, since world-making is a mimetic process. So it’s actually about dismantling hierarchies and no longer descending into the fiction. In literary scholarship, we operate with a well-defined concept of fiction. Even when the author uses his real name, he’s the intra-diegetic author. He remains a fiction.

Graw: But what’s called auto-fiction also implies that the distinction between real and fictional, between authentic and staged, is left in abeyance?

Waterfeld: I read the Transmedia Manifest not as a standalone theory but more as a position paper put out by a group of people with backgrounds in different disciplines. And that makes it inherently interesting to me. I recognized parallels with the early Romantic idea of progressive universal poetry, which hinges on duplicity as opposed to the dualism of the two planes of existence, finitude and infinitude, which is to say, reality and fiction; on the dialectical interrelation and on building awareness of it, for example, by breaking the fiction, addressing the reader, self-reference, which in turn gesture toward the mimetic making of the world. Poetry as a tool of emancipation.

Friedmann: On day X, a collective formed that meets every two days and is engaged in political activities. That’s a reality. Even if we operate under the pretense of theatrical production and thus a guise of fiction, what’s real is still real. Fiction and reality blur into each other or evolve in parallel. That, to my mind, is where the productive tension comes from.

Graw: So the strategy is that whenever someone tries to commit you to what’s real you say that that reality is a fiction, staged, and whenever someone dismisses what you do as mere staging, you insist on the dimension of the real. But what do you mean by “transmedia”? Does the term describe a hybrid conception of media, one in which they are intrinsically heterogeneous and blend into each other? That sort of conception of media had its place at Castorf’s Volksbühne as well.

Press conference, 09.22.2017

Press conference, 09.22.2017

Waterfeld: Our idea of transmedia goes beyond the notion of hybridity. I do think the Transmedia Manifest describes our activities fairly well. For example, the notion that narrative is no longer linear, but rather, is supplanted by a story-universe with different but interrelated strands; and that its addressee is no longer the reader, beholder, or spectator but the “experiencer.” And no matter what he does – even if he’s just there and refuses to become involved and rejects it, that’s another narrative strand, each of which the transmedia people call “rabbit holes.” There are different entryways into the work. For example, if someone overheard our conversation right now and then went to the homepage and watched the film (https://b6112.de/), he would’ve created a rabbit hole. So reality is shot through with holes through which one can enter the story universe, and within that story, all “experiencers” can communicate and thereby flesh out their own narrative strands. And literature has always functioned that way. So “transmedia” is about the future of storytelling in the digital age. It’s about the interaction of experiencers who are no longer mere consumers.

Graw: What this subject experiences seems to have a lot in common with the ideal of participation in postmodern art. However, among art historians, that ideal has been fairly controversial since the 1990s. Rather than see the viewer’s participation as emancipatory, many regard how she’s drawn in as problematic or even infantilizing: e.g., all she can really do is relate to a given proposition. What’s more, the participatory ideal suggests that there’s an aesthetic experience that’s accessible to everyone when in reality that experience remains bound up with certain prerequisites and hierarchies. Museums embrace work designed to solicit participation in part because it lends art the appearance of accessibility and dresses it up as an event.

Waterfeld: “Participation” is obviously a fraught concept as long as we live under capitalism. As long as art must generate profits to sustain its originator or an institution, participation is a problematic idea. But that’s no reason to think that things can’t change—it’s not a law of nature. In a different world, the concept of participation would have distinctly positive implications. Still, the fact that value can be extracted from art raises a lot of problems that exist in the framework of this economic system. Participation in and of itself doesn’t carry negative connotations.

Graw: But aren’t the mechanisms of value extraction that are operative in the visual arts very different from those in the theater world? In the visual arts, objects are being traded (even performance art yields marketable relics, props, documentary materials), whereas the theatrical production is a live experience; spectators pay for admission but no objects with speculative potential are produced. And then the ideal of participation is no less controversial in the theater.

Friedmann: At the core of theater is a power that should be harnessed to inspire people to think hard and ask questions. The spectator should be faced with something that compels him to ponder what he’s just experienced. I’m not saying that theater cannot also, in this, be a source of entertainment, but the spectator should be taken seriously. I hope that our project has initiated in the viewer a process of genuine change, bringing him to consider issues that he might’ve preferred, consciously or not, to side step. Even if parts of the theater world have unfortunately become very exclusive, theater should not be used for the purposes of capitalist manipulation.

Graw: But there’s an essential difference between producers and consumers that the ideal of participation tends to blur. Unlike the consumer, the producer bears responsibility for her output, a responsibility that’s also reflected in her authorship and the rights that come with it. The hope of turning the consumer into a producer, it seems to me, glosses over these producer’s privileges.

Friedmann: Privileges of this sort, I believe, have no place in a situation in which art serves as a means to a higher end.

Graw: What exactly is the benefit of trying to suspend the distinction between production and consumption?

Waterfeld: Right now, there’s the need for art to politicize people. As long as we live in this sick system of global slavery, that’s the pressing need, regardless of whether it’s literature, painting, or, in our case, theater. In a different social system, the primary need may be for theater and other art forms to entertain people. But I don’t see the point of a literature that doesn’t engage with contemporary realities and doesn’t insist on wanting to make a change. I can’t wrap my head around how it’s even possible to be making art today without seeking to change social realities. You have to be so absolutely ignorant and self-satisfied to do that. Like, I’m perfectly fine—so now I can write apolitical crime fiction. After all, I don’t have a problem. That’s an attitude I reject as long as we live in this barbaric situation.

Graw: The problem is just that by committing art to the goal of social change you tend to lash it to a purpose and turn it into a mere means to an end. Dealing with superficially political content doesn’t necessarily make art political. When I visited the occupied Volksbühne in the evenings, I thought it was wonderful to see the organizational skills (and sense of humor) that went into the occupation. At the same time, I wondered why you didn’t come out with a stronger visual-creative statement. In that regard, what I saw was more reminiscent of the typical squat aesthetic. Why didn’t you devise a distinctive artistic program and visual vocabulary?

Waterfeld: We had a variety of ideas. But how do you implement those with no budget? We had a studio, which we paid rent for, but we had no funding for the film production or even one of the actions. We all plowed a lot of our own money into that action, since we were all volunteers. There was just no way to make certain things, like the visual materials, happen without a budget. Our logo is the Giacometti cube from different perspectives. Jakob Gerber from the film team has wonderful things to say about that choice of logo. A second visual element is the bomb: the work of art.

Graw: What led you to choose the bomb motif, which I earlier interpreted as a rocket?

Waterfeld: That’s our film team’s humorous take on North Korea. They wouldn’t want to live there, no do they have any intention of defending the North Korean system. But the nuclear danger has been a latent presence for years—by which I don’t mean that we’re constantly scared of nuclear war. Still, we thought it was remarkable that the newest American nuclear bomb, the B61-12, is built to be as small as possible. In the past, descriptions of these bombs always highlighted that they were the biggest, most massive, capable of annihilating everything. Now the goal is to develop the smallest nuclear bomb. That’s a development we find very scary, because these bombs are built to actually be used. And the capitalist edifice has started to wobble. The thousands of dead bodies drifting in the Mediterranean Sea are not the only evidence. Europe is anxious to defend its wealth against those who are rushing toward it. At the same time, the Americans are starting to build small nuclear weapons. The nuclear war threat scenario is being maintained. So in this humorous perspective, a nuclear bomb of one’s own is what it takes to be heard and stay part of the conversation. That’s why we built ours. It’s a faithful replica, made with the simplest of means.

Graw: Yes, that bomb was an effective artistic-visual statement. Otherwise, however, a visitor to the occupied Volksbühne was reminded of a mixture of the typical squat aesthetic and the atmosphere of a self-help group. I don’t even necessarily mean that critically—it’s simply a look that’s almost impossible to avoid when self-organized groups come together for political action.

Waterfeld: We’d also made uniforms featuring the Giacometti cube. Unfortunately, almost all of them were stolen after the first night. We had two left.

Graw: What did those uniforms look like?

Waterfeld: They were blue workers’ overalls we’d been given by P14, the Volksbühne’s youth theater ensemble, with the Giacometti cube spray-painted on them. People thought they were cool and so they swiped them. We had twenty of them. Now there are two left, and in the end it was simply a question of money whether we’d make new ones. And then we’d chosen that legend “Doch Kunst” (“Art After All”) for the banner because we liked the message it sent, even though we’d have wished for a different aesthetic.

Graw: Why didn’t you ask visual artists to do the design for the banner or the printed matter?

Waterfeld: Oh, we did. It wasn’t easy, actually. Over the past nine months, the cooperation committee I’m on has looked for people who would work with us. We fanned out and talked to people: to institutions, to artists, to actors. I think the many rejections we received were a product of the fear that being publicly seen as associated with a ragtag posse of pseudo-artists would be a career-endangering move. We observed and drew up profiles of eight types of cooperation. Anyone who contacted us about working with us received an email listing these eight forms. Number eight was the one we welcomed least: it let the would-be partners protect their careers by waiting and seeing whether the project would turn out a success, and if it did, they would retrospectively pledge their support and claim that they’d been part of it from the start. A whole number of people chose this mode of cooperation, no doubt out of fear. Given the heterogeneous and unfunded troupe we were, they couldn’t imagine that our project would be a success. They simply didn’t take us seriously.

Friedmann: As far as I know, the big production was originally planned for the summer of 2017. Dercon, who was in on what was going on, had security guards walk around the Volksbühne, hoping to safeguard the premises by shutting out the production, which would’ve featured numerous artists from all fields. There was a complete schedule, many people were interested, and there would’ve been an opportunity to enjoy this production for free: artists didn’t have to be someone to make their art and spectators didn’t have to be someone to enjoy it. Theater minus the exclusivity factor, accessible to everyone. Defying a tendency—and this brings me back to what we talked about a moment ago—that risks losing sight of the meaning of art, and especially of the meaning of the kind of theater I want to make.

Graw: So the plan for a production, a detailed program, with plays, directors, actors, had been worked out before the occupation proper?

Waterfeld: Yes, a program had been drawn up for July. But there were concerns that many involved would be away for August. A discussion was held where people said that a production involving, by then, 3,000 people couldn’t be canceled on account of some individuals’ vacation plans, and so the security service was hired. We’d prepared a schedule for three months: plays, concerts, performances, photography exhibitions, art … always leaving room for people who would learn about the production once it was on and want to be part of it. We had a plan: go in with a program that would generate attention and then discuss and create something together. We would’ve advanced a program for three months and then disbanded on day X to ensure the whole thing wouldn’t turn into a job-creation scheme, to allow a new collective to form.

Graw: You saw yourselves more as enablers or midwives of a new Volksbühne that you intended to initiate?

„NADRYW- Die Volksbühne als letzte Realität", documentary, 2017 (Dir.: Lydia Dykier)

„NADRYW- Die Volksbühne als letzte Realität", documentary, 2017 (Dir.: Lydia Dykier)

Waterfeld: Exactly. For example, I personally had no intention of being stuck for the next two years in some collective, some administrative structure, and devote all my energy to it. I’m a writer, I want to work by myself from home. It was just important to me to set something in motion, to get a project going.

Graw: What happened to the program you’d envisioned for the summer?

Waterfeld: Some things did happen. For instance, Milo Rau wanted to do something the day after the eviction, and Cyril Tuschi planned to stage an interactive event featuring virtual reality glasses and a ballet ensemble in July. He wanted to use the ballet hall for several weeks or months. These items on the agenda had to be canceled when the original date was called off. There were people who were livid. They said: I went to such great lengths and you postpone just like that? You can’t do that.

Friedmann: Ton Steine Scherben were going to come and play as well – in the end they simply performed in front of the building. That’s something that bears emphasis today: Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, the square, is still open and people can use it to make art – that hasn’t changed and won’t change. Our goal was never to disrupt ongoing rehearsals and projects. That’s why, once the initial schedule fell through, we needed to set a new date fairly quickly. Bringing all those people back in would’ve been too risky, because if we’d have to cancel again, that would’ve cost them more of their time and money than we could reasonably ask of them. Still, the people who came during the production witnessed a lot of very different and in some cases highly sophisticated art being made. It was fantastic. A space for club collectives, a space for conversation and politics, a space for art. Everything at the same time, for and with everyone. And keep in mind, we had only six days. Six days!

Waterfeld: René Pollesch, too, promised to put old plays or new productions on stage under the collective artistic direction. And other people … Another goal was to meet the spectators’ demand to be able to see the plays in the repertoire again.

Graw: How did Castorf’s troupe respond to the invitation in your press release to get involved?

Waterfeld: Many of them showed up. Sophie Rois showed up; Pollesch is directing productions in three cities right now, but he showed up whenever he found the time. Many came and many more told us that they had engagements but wanted to come as soon as possible. Generally, a lot of people – including the entire artistic staff – were willing to pitch in. At one point, we screened our film NADRYW about the Volksbühne at Kino Babylon and everyone knew about it and no one had a problem with it. Unfortunately, we had to edit out Sophie Rois because she’s still on the Volksbühne’s payroll, but all other staff members who appear in the film are perfectly clear about what they think of the liquidation of their theater.

Graw: But there was the report from official sources that a majority of the clerical and technical staff at the Volksbühne wanted to end the occupation.

Waterfeld: Yes, that’s about the stagecraft employees. I was present during the conversation with the staff that Dercon initiated. It’s important to note that this was far from a plenary meeting – only about 90 out of a total staff of 240 were there. And only permanent employees were allowed to speak. People actually raised their hands and Dercon said: You are not invited to speak here. He went over to the person in question and shut them up before they could say what they thought. The discussion went back and forth. In the end it was five very vocal, very macho men who really raised hell. They prevented a genuine dialogue and berated us and were inconsiderate. These five gentlemen would never have agreed to our idea, also for political reasons. But among the rest, many showed up and I’m sure that a solution could’ve been found that the large majority of the staff would’ve liked. I’m positive of this.

Friedmann: From the very beginning, the group was clear about its respect for the institution, which always extended to the staff as well. And the fact that that promise was kept wasn’t lost on the employees. Unfortunately, it wasn’t always possible to communicate effectively, for the reasons Sarah just described. Nonetheless, every effort was made until the very end to get them to talk to us.

Waterfeld: We wanted to meet with the entire staff on Monday (September 25) morning, but the city officials stopped us. They said they were still in talks with Dercon and asked us to abstain from calling the meeting. We diplomatically agreed. And then the officials came and presented a “solution” that was basically a joke.

Graw: What did that “solution” look like?

Waterfeld: That certain people weren’t allowed to speak. It was mostly men who spoke up. I then insisted on a quota-based list of speakers—not a chance. That’s how a genuine conversation involving everyone was prevented. We’d worked with several lawyers and an expert in labor law to draw up a paper for that Friday (September 22): a preprinted form with a legal notice that staffers shouldn’t speak about us in positive terms because that might be interpreted as damaging to their employer’s interests and could have resulted in their immediate termination. So we explicitly told the staff: talk to Dercon, to your employer, before you express your views.

Graw: So you didn’t lose sight of the risks to the staff, which I think was very responsible-minded and prudent. How did the visual artists engaged by the new Volksbühne, like Tino Sehgal or Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff, respond to what you were doing? As far as I know, they never publicly took a stance on the occupation.

Waterfeld: Susanne Kennedy was there during the negotiations with the staff, but I don’t remember whether she was allowed to speak. We met Tino Sehgal when we moved into the building. He had a rehearsal going on at the time and was cool with us. Mohammad Al Attar approached us and wanted to talk. And Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff were there the whole time. They said they were in the middle of a video project and asked us whether it was ok for them to keep working on it. People kept on doing what they were doing; that was the point of our action. During the entire six days, they were filming and interviewing people and working on their art.

Graw: What’s your view today of Dercon’s offer to let you use the Grüner Salon and the Pavilion? Does that offer still stand?

Waterfeld: Before I answer, let me quickly sketch the history behind the occupation. What happened was that a group of Volksbühne staffers approached the occupiers of the Institute of Sociology at Humboldt University and asked whether they couldn’t do something similar for them. There’d been the open letter against Dercon. Of the total staff, 177 people had said that they didn’t want this kind of radical change. They advocated renegotiating the directorship. Some of them got in touch with the Institute of Sociology occupiers and there was an ongoing exchange of ideas. The occupiers were students and people from political autonomous groups. When I joined in March, the meetings were still held on the rehearsal stage. Members of the artistic and technical staff were involved, as were actors.

Graw: So your group originally goes back to an initiative started by Volksbühne employees?

Friedmann: Correct. When politicians decide as they see fit behind closed doors, people will look for alternatives.

Waterfeld: Before I came in, people had met over the course of weeks and discussed together what an occupation might look like. But the Volksbühne employees ultimately pulled back from the plan. When they realized that the action was actually going to happen, they got scared, perhaps understandably. Scared for their jobs, scared for what would happen if there were injuries or if the landmarked building suffered damage. But these are all situations that can arise in the course of a theater’s normal operation, too.

Graw: There was also the petition initiated by Evelyn Annuß, which more than 50,000 people have signed by now. But the culture pages in the papers repeatedly reported that only a fraction of the signatories showed their faces in the occupied Volksbühne.

Waterfeld: Well, I wrote to the petition’s initial signatories just before the occupation. Two women got back to me who wanted to be named on our list of supporters, and one man wrote to say that he absolutely didn’t want anything to do with it.

Graw: That’s disappointing feedback! Especially considering that the petition and your intervention are in agreement that it’s not about Dercon personally but about a critique of the social and political implications of the way the new director was appointed.

Friedmann: It’s important to see that several initiatives can act in parallel, pursuing their respective goals without defeating each other, and that they’re often even motivated by the same issues. Many friends in the visual arts told us straight up, “Hey, if you’re against gentrification, go out and occupy a different building, but leave our theater alone.” In reality, fighting on both fronts can be of advantage to everyone involved and even strengthen our hand in every respect. This brings us back to the question of how art can function in this context.

Graw: That’s a reproach leveled against you by many commentators: if you’re against gentrification, why don’t you occupy a building that’s owned by real estate speculators? With that in mind, maybe you can explain what you see as the symbolic significance of occupying the Volksbühne. Why did it have to be this particular institution?

Friedmann: It’s precisely with regard to gentrification that the Volksbühne is a symbol of the big sellout of the city that’s going on right now, with the low-income population being pushed out of the center. Also, it’s important to draw the connection between art and political alternatives. The political system has become so gridlocked that a creative experiment appears to be the only way to try something new or illuminate things from a different angle. Acting in a sheltered space has advantages because that space is allowed to be alive and vibrant and people take something away from it. Our action spoke to so many people precisely because it was the Volksbühne, and it would’ve been justifiable even as an occupation because the Volksbühne has always also been a place of vigorous political engagement. It’s time people understood that art and politics are not wholly separate battlefields—both are about people who, as in this instance, are stuck in a deadlock that needs to be broken. If art is no longer allowed to be radical, its potential goes unrecognized.

Waterfeld: To my mind, the elimination, on Dercon’s direction, of the words “on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz” from the Volksbühne’s name is an enormous affront. It severs the institution’s ties to the urban fabric around it and erases the political aspirations it has stood for. The name Rosa Luxemburg, after all, symbolizes the possibility of a different system. In our film, Castorf says about the name change that to his mind it’s like defiling a corpse. That’s a wonderful image for this strategy, which, when you think about it, is absolutely unacceptable.

Graw: But might it not be argued that an incoming director should be allowed to change an institution’s name? What matters are the implications that rebranding has. And the transformation of the “Volksbühne on Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz” into a “Volksbühne Berlin” explicitly abandons the reference to a specific place with its history and the association with Rosa Luxemburg’s political resistance and the history of the founding of the Communist Party. Rejecting this purging of politics from the Volksbühne, your press release championed the vision of a city in which “all citizens” can “peacefully develop their potentials in equivalent circumstances.” What exactly do you mean by “equivalent circumstances”? That all conditions in life, regardless of how much money someone has or their status, are seen as equally valuable? And would this value be an ethical or economic concept?

WWaterfeld: We mean equivalent circumstances in a socialist, communist sense. We don’t get why a surgeon should earn more than a housecleaner. I could mention a thousand other examples. We use the word “equivalence” to avoid the term “egalitarian” with its strongly negative connotations. Still, we wanted to set the bar high, because we’re concerned not just with the city but with the entire planet. And of course that’s a cliché, too. When someone asks, Why are you doing that, the stereotypical answer is: For world revolution. And equivalence, in this context, means that people should all get the same for whatever they do.

Graw: Equal pay for unequal work.

Waterfeld: Yes. Part of the idea of communism, after all, is the abolition of the monetary system. From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

Graw: But what we saw in actually existing socialism was that inequalities and hierarchies creep into such a system as well. And I know from my own experience in self-organized groups that inequalities persist in them, as does some men’s propensity for macho-style dominance. Have you faced such problems in your group and what do you do about them?

Waterfeld: We mustn’t forget that, even though we live in a democracy, we’ve never actually learned democratic processes. I have two children myself and wish they’d been taught an understanding of democracy in kindergarten at the latest. There are plenty of efforts in that direction, like the democratic daycare centers and schools in Berlin. Still, the structures we live in are ultimately authoritarian through and through. In kindergarten, in school, at university, we’re always told what to do and not to do: when to get up, when to perform, etc. All the while, the pretense is that we’re involved in every decision and make self-determined choices. But the child doesn’t experience this coercion as a self-organized process. In my perception, our school system is militaristic and sadistic. Then, once we’re grownups, we’re told we’re free to make our own choices because we supposedly live in a democracy.

** Graw:** But as we saw in the 1990s, the ideal of self-determination you seem to be advocating proved a perfect correlate of the requirements of a neoliberal economy. The autonomous subject, an agent who both takes responsibility for and exploits himself, is in demand in the labor market. What’s more, the ideal of self-determination tends to blind us to the extent to which processes of subjectivation are ultimately subject to heteronomous forces.

Friedmann: But who determines what exactly that heteronomy looks like?

Graw: That’s a good point, although one may also find the repressive structures in school and at university enjoyable, experiencing them in the individual perspective as a kind of heteronomy that lends stability and structure to one’s own life.

Friedmann: But that’s very different from one person to the next.

Waterfeld: When I was at university, we still studied toward a Magister degree. That was a comparatively speaking quite self-determined form of study. All of that has now been rolled back. I have many friends who work in academia. Students in literature classes today are given exams with multiple-choice questions. In terms of self-determination, we’re actually regressing at a rapid pace – it’s an illusion to think that people in the academic world are self-determined in what they do. What we’re sold as self-determination in settings structured for purposes of commercial exploitation is different from what self-determination actually means.

Graw: That’s true – we’d need to draw distinctions between different conceptions of self-determination. With few exceptions, the culture pages of Germany’s newspapers responded to your action in astonishingly condescending tones. You were called “parochial anti-gentrification activists,” the occupied Volksbühne was described as a “playground for kooks.” What do you make of this hostility, this refusal to engage with your ideas? Do you think it might be motivated, psychoanalytically speaking, by the journalists’ envy of your courage because they themselves had to loose that courage long ago?

Waterfeld: Yes, but then even Castorf himself called us “boys and girls,” although he knows perfectly well that we’re not boys and girls. He was presumably afraid that we’d turn out to be dilettantes – and this from the director who put the city’s freaks on his stage, no matter that they weren’t trained actors. So that he of all people would say that he saw dilettantism taking hold, that’s almost a joke.

Friedmann: Who decides what’s dilettantism and what isn’t? Isn’t art still in the eye of the beholder? “To each time its [own] art, to art its [own] freedom.” As long as people passionately stand for relevant issues, there’s no such thing as dilettantism in the theater.

Waterfeld: Yes there is, though I can only speak for myself: when I go, say, to Berlin’s Gorki-Theater or to the Berliner Ensemble, I feel like I’m being taken for a ride. I watch a show like “Atlas des Kommunismus” at the Gorki, and to me that feels like youth theater. That sort of play may have its legitimate purpose, but people who are more interested in questioning themselves or what they think they know no longer have an aesthetic home. The old Volksbühne was different—I’d leave after a show and think, I’d never heard this or that philosopher’s name, why does the production invoke him, what does he say? That never happens with any of the other theaters, not even with the Berliner Ensemble. I feel like I’m getting hoodwinked and I’m never challenged as an intellectual.

Graw: I kind of feel the same way. I wanted to come back to the much-touted offer from the director’s office to let you use the Grüner Salon and the Pavilion – where do things stand in that regard?

Waterfeld: Even if the offer still stood, it would be irrelevant to our current planning. We’ve stated our demand: we want be inside the space within two years to work there with our collective. Managing that kind of stage in the longer term requires putting together the financing and an organization. We figure we need two years to do that. That’s our demand, that’s “B61-12,” that’s what our press release says. As long as there’s no new text, no new work of art, our concept hasn’t changed.

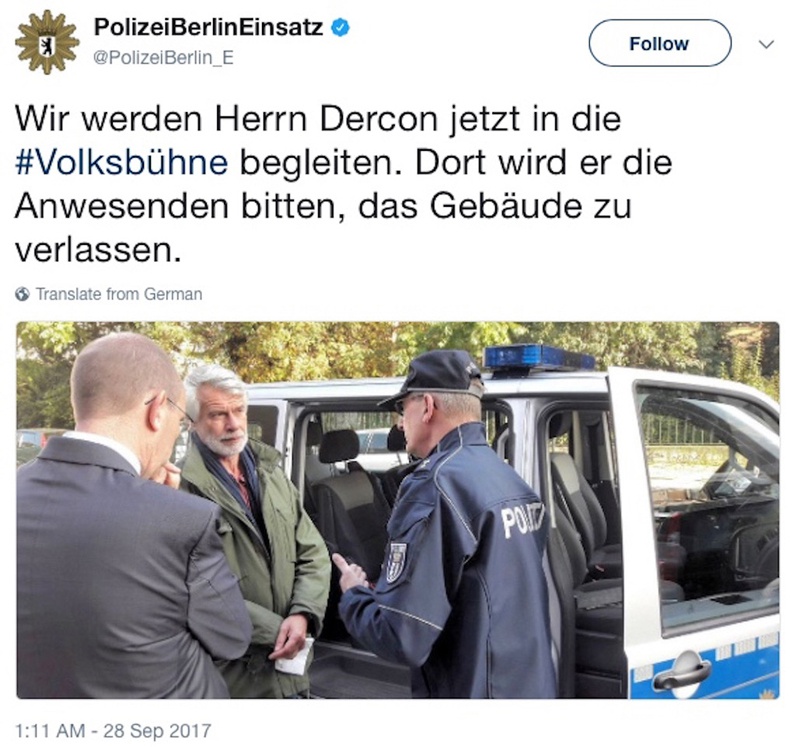

Graw: Ok – but you’re no longer inside the Volksbühne. Dercon called the police and had the occupiers evicted.

Waterfeld: We’re not inside right now.

Graw: And what’s going to happen now?

Waterfeld: I can’t give you specifics yet. But the plan stands. We’re still interested in making our work of art a reality. All of it.

Friedmann: What also surprised me was that we were really given no more than thirty minutes to clear out of the building. We were still going back days later to clean up and move stuff out. And on this point it actually is Dercon personally that I’m critical of …

Waterfeld: … the fact that he called the police without telling us that that was what he was going to do. He could’ve come by and let us know.

Friedmann: We were in the middle of negotiations, which were unilaterally terminated by the eviction.

Waterfeld: That’s the political scandal. That a senator of culture from the Left allowed the eviction to happen this way. My impression is that the parliamentary left is in self-destruction mode. A brilliant move would’ve been if Lederer had stepped down as senator of culture and made common cause with our collective. That way he would’ve signaled that something important is at stake and he’s part of it. People would’ve joined his party in droves because they would’ve realized: Wow, that guy is a real leftist! He gets it. But right now the “Left” is steering a social-democratic course, which is pointless, since there’s another party for that. Especially now, with the Alternative for Germany inside the parliament, the opportunity would’ve been perfect for the Left to take a clear stand. What makes it worse is that, on the day of the eviction, the Alternative put forward that urgent motion to evict. And the Left complied with that motion in an act of preemptive obedience instead of opposing it and then introducing a politically similar motion later on. Actually yielding to the Alternative for Germany on this point was a pathetic display of political incompetence that’s truly insane and shocking.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Anna-Sophie Friedmann (b 1992 in Vienna) is an actress and activist. She is part of the non-profit theater cooperation „Traumschüff geG“, as well as the collective „B6112“. She is currently studying acting at HfS „Ernst Busch“ Berlin.

Sarah Waterfeld (b 1981 in Berlin) is an author and scholar of literature. She has taught classes on „Transmedia strategies of political intervention“ at the University in Potsdam. Her transmedia two-novell-series („Sex mit Gysi“ and „Was vom Hummer übrig blieb“), byproducts of her 2012 candidacy as the head of the German party „Die Linke“, were published in 2015 and 16 respectively. She co-initiated „B6112“ and was spokesperson for the „Staub zu Glitzer“-collective.

Isabelle Graw is the publisher of Texte zur Kunst.