Between you and me A Correspondence on Autofiction in Contemporary Literature between Isabelle Graw and Brigitte Weingart

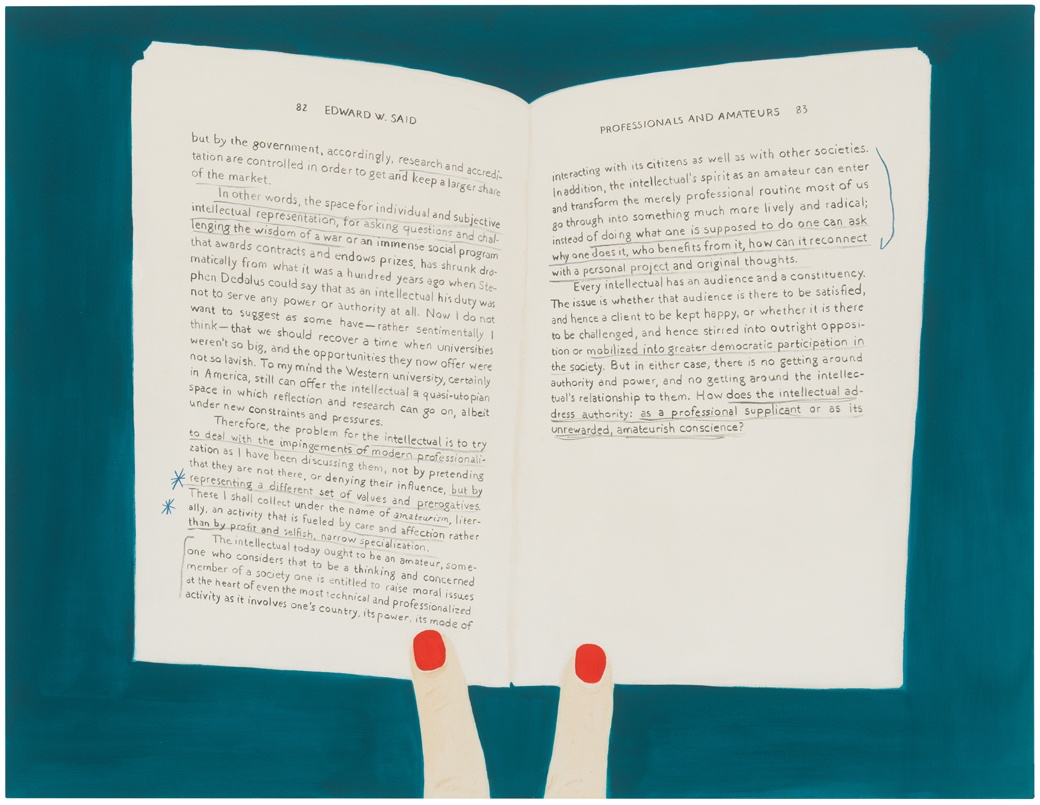

Frances Stark, „Reading Edward Said’s Representations of the Intellectual from 1994“, 2019

Dear Brigitte,

I mentioned it when we were sitting together a little while ago, drawing up plans for the issue that readers now hold in their hands: in recent years, I’ve devoured more contemporary literature than ever before. In particular, I’ve really gotten into the work of writers (many of them women) associated with the label “autofiction” – Annie Ernaux and Deborah Levy are among the most prominent examples – who portray both their fictional and putatively authentic “selves” as nodes in which social forces intersect. I had not paid so much attention to contemporary literature for 30 years (it has also not been so relevant to Texte zur Kunst), [1] but now I find myself especially interested in living writers – besides the two I just mentioned, I’ve been reading Natascha Wodin, Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh, Ben Lerner, Rachel Kushner, Angelika Klüssendorf, Violaine Huisman, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and many others. What I think they achieve, each in his or her own way, is a poignant rendition of how the new coercive social pressures take hold of their subjects (and their consciousnesses). Yet the “I” that makes its comeback in their books is not one that (as in Karl Ove Knausgaard [2] ) merely records its lived life in a documentary register. Rather, it’s conceived as social through and through: molded in specific ways both by the prevailing class structures and by sexist and racist determinations, which are also negotiated and articulated in the act of writing. This I, we might say, is more than a structural effect and also not just a confessional subject striving for authenticity.

Ernaux, in particular, has rightly been praised for having transposed biographical material into a sort of social biography. And indeed, she and writers like Levy and Cusk have produced vivid descriptions of social constraints; more precisely, of the personal dimensions of capitalism: how it infiltrates our minds and even shapes our life crises into predetermined structural patterns, how it directs our desires and inscribes itself into our own self-understanding; all of this is described in these books. Right now, it seems to me, literature is doing a very good job of addressing these concerns, also in comparison to much of the visual art being produced today: perhaps because literature is better equipped to give a trenchant and straightforward representation of the interplay between technologies of power and techniques of the self.

Interesting enough is that it is the social milieu of art, the vaunted “art world,” that often serves as a glamorous backdrop for events, especially in the books of US-American authors like Moshfegh, Lerner, and Kushner.” [3] Being fundamentally reproducible, books have less value potential as symbolic objects than the unique physical things made by visual artists, and so it can seem like literature is trying to ride the coattails of visual art, which has seen considerable symbolic and market appreciation in recent years. For example, when the nameless protagonist of Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018) works in a gallery, her status as a culturally informed and socially privileged hipster is confirmed.

George Romney, „Lady Seated at a Table“, ca. 1775

Yet the authorial I we encounter in these books is also not truly fictional, although the concept of “autofiction” seems to suggest as much. Whereas Roland Barthes had previously introduced his opening autofictional scene in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (1975) with the assertion that the voice we hear is that of a “character in a novel,” Deborah Levy, in The Cost of Living (2019), characterizes her (female) literary self as someone who “is close to myself and yet is not myself.” [4] The assertion of fictionality – which Barthes underscores with his frequent use of the distancing third-person singular pronoun “he” – has given way, in Levy and many other writers, to an I that’s fictional but nonetheless has much in common with the author: a literary figure, therefore, but one that remains anchored in the author’s I (and thus also in her social conditions).

If this I is social through and through (and, unlike Barthes’s alter ego, doesn’t seek to transcend its social situation), that’s also due to its being marked as “female”: a marker that cannot be stripped away, it incessantly confronts the author’s fictional-authentic I with social ascriptions that assign her a place as “woman.” I can’t help wondering, though: To what extent does this I of autofiction achieve something new? Or is it merely a continuation of tried-and-true literary conceits?

Love, Isabelle

Dear Isabelle,

your observations concerning what’s currently being debated – and clearly also hyped [5] – as “autofiction” make a lot of sense to me, which is exactly what has me wondering whether this might not at least in part be a case of old wine in new bottles. Much of what you describe is at work in older texts, like the literature of the 1960s and ’70s: take, for example, Hubert Fichte, whose œuvre happens to be enjoying yet another revival these days. [6] Over the many volumes of his Geschichte der Empfindlichkeit (History of Sensibility), beginning in 1974, Fichte has his alter ego Jäcki oscillate between being based on lived life (auto-) and a perpetual “reinvention” of the character – with the latter being the site of utopian sexual fantasies (-fiction?) and theoretical readings and studies in ethnology. Moreover, Fichte certainly tried to devise alternative modes of writing (by, for example, developing a dialogical format in which the speakers’ lines are set apart only by dashes, thereby “desubjectivating” them – a technique he also used in the transcription of his interviews, and which bears some distant resemblance to the way Rachel Cusk integrates other voices). Or take Peter Handke’s Children’s Story (1981), in which “the adult” or “the man” stands in for the place where one might expect an I. In his A Sorrow Beyond Dreams (1972), on the other hand, it is an I who mourns the mother’s death while recounting her life as a collective biography in a way that, as in Ernaux, transforms an account of symptoms into a social diagnostic. Similarly, Rainald Goetz’s balancing act between the total emphasis on subjectivity on the one hand and writing as mere recording of preexisting discourse on the other would merit more than the footnote in which you’ve mentioned him; Kathy Acker sends her regards; etcetera, etcetera (one hardly dares to open that Pandora’s box because so many examples come to mind).

What’s more, even in “traditional” autobiography we rarely come across a naive conception of authenticity, but regularly encounter reflections on the constitutive function of narration for one’s own life story, on how the text – not least through its imposition of linearity – “co-authors” the putative “self” (e.g., Lawrence Sterne’s extravagantly hyperbolic Tristram Shandy, whose first volumes came out in 1759, and which pretty much invented metanarration). In the texts that are now treated as “autofiction,” however they differ from each other, as in some of the precursors just mentioned, what seems to have become established as standard is a kind of postmodern upgrade of autobiographical narrative: instead of assuming a complex identity, which is then depicted in the text, the ego or its placeholder restages itself as a resonant body of perceptions, conversations, social relationships, art experiences, readings (without ever abandoning the idea that this self is anchored in its own corporeality; that may be something we want to get back to). Instead of the teleological construction of a life as an integral whole, we find the fragment, the dialogical form (as in the epistolary format we’ve chosen), or else an episodic structure, often prompted by a private crisis or a transformation that, for good reason, is assumed to be generalizable (a failed marriage or the experience of parenthood leads to an analysis of gender relations; transgendering to biopolitics; the escape of a “transfuge de classe” [7] from his or her original milieu to class society; police violence against people of color to racial politics). From the legacy of metafiction, which, after its first heyday in Romantic literature, has come to be regarded as a hallmark of postmodern writing, it’s perhaps not so much the reflection on the scene of writing as, rather, the focus on questions of memory, of the labor of recollection (again, in relation to micro- as well as macro-social trauma) that has found its way into autofictional texts.

Wash Westmoreland, „Colette“, 2018, Filmstill

I would nevertheless agree with you that there is something emerging in the relation between auto- and author in the contemporary texts we have in mind here that does strike me as somewhat new: while the “I,” in all its fictionality, “nonetheless has much in common with the author,” as you put it, we are facing something other than just the return of an author we’d written off as dead. Rather, it’s an arrangement that lets the writer have her authorial cake and eat it too: to anchor the character in the author’s I vouches for credibility, which is not (no longer?) guaranteed by the factuality of the writing. I would say that, as a strategy of authentication, this reliance on the I is also related to the discourses of the fake and the crisis of the factual (which the same theorists who proclaimed the death of the author are said to have helped cause) – and since falling back on constructivist findings and invoking objective truths are no longer an option, it makes sense to foreground the genuineness of the person, and thus authenticity. (Speaking of having one’s cake and eating it too: after all, the hybrid term “autofiction” happens already to imply both – the conjunction of the author’s own life with the [postmodern] awareness of the problems of representing the factual, which is always already undermined by selection, arrangement, narratability, etcetera, and thus by quasi-fictional elements …).

Which in turn brings us to the question of why the label is so in vogue right now, the answer to which must surely include an interrogation of its marketing effects: “As it happens,” Christian Lorentzen writes, “the term’s coining occurred not in a work of criticism but in the blurb on the back of the French novelist Serge Doubrovsky’s book Fils in the late 1970s: […] So autofiction came to us as part of the language of commercial promotion, a way of marketing as new something almost as old as writing itself: the blending of the real and the invented.” [8]

Love, Brigitte

Dear Brigitte,

no doubt you’re right: the “I” of autofiction and its oscillation between the promise of authenticity and literary stagecraft is not a novel phenomenon. Even Rousseau concedes on the very first page of his Confessions (1781) that, in his endeavor to give a truthful account, he may nonetheless not have succeeded in getting rid of all “ornamentation.” [9] In other words, the “truth” he proposes to reveal to us in this primal scene of autobiography is still a product of literary stylization.

You’ve quoted Lorentzen, who notes that the autofiction label came into being in part as a marketing device. A similar phenomenon can be observed in visual art: if you consider categorizations such as “Minimal art” or “relational aesthetics,” these are labels that, just like “autofiction,” do not just indicate a new genre, they also help sell the products on which they are stamped. Not coincidentally, writers like Cusk, Ben Lerner, and Angelika Klüssendorf actually do reflect on the peculiar economy of literature, incorporating scenes of the marketing of their work – book tours, readings, meetings with editors – into their texts. The writing, you might say, engages with the fact that it exists in a specific economy, or more specifically, that it circulates in a media society and celebrity culture in which public interest is invariably focused on the person behind the product. The texts themselves explicitly address the question of how the writer handles situations that are shaped by the marked desire for a kind of intimate interaction: authors are now more than ever expected to be personally involved in promoting their books and, like celebrities in other fields, package their lives for media dissemination – disciplines that Cusk happens to have mastered extremely well. And conversely, the more “lived life” their books seem to contain, for example by reflecting (or seeming to reflect) the writer’s coping with the challenges of motherhood or getting over a breakup, the greater their marketing potential will be.

Jean-Paul Sartre, by the way, already noted the nexus between a literary “I” putting itself on display and the social recognition such self-exposure garners in a media society, as well as the phenomenon of the author’s seeming to “live” inside his book. [10] In his autobiographical project The Words (1963), he gives an entertaining sketch of how he became who he claimed to be in the eyes of others. His “I,” he writes, existed only “for show.” [11] And this need to produce the “I” with a view to certain social expectations, we might say, has become even more acute in the age of celebrity culture. Sartre offers a striking image for the kind of situation in which the writer as the “giver” becomes his or her own gift: “I am taken up, opened out, spread on the table, smoothed with the flat of the hand and sometimes made to crack.” [12] Transmuted into his book, the author can be heard “cracking” in its spine: this anthropomorphic equation of work and writer, too, lives on in today’s autofiction.

At this point we should perhaps also think about the linkage between the current fashion for autofiction and our increasingly digital economy: if our so-called life events are traded as a valuable resource, especially on social media, this has to have an impact on literary production. Might it be that the putative “lives” of authors writing in the autofictional mode, being explicitly staged productions, prove so popular because many people are now grooming their online personae and engaging in social-media self-marketing?

But I think there’s yet another reason why the lives of others (and especially their supposedly authentic aspects) exert such a universal fascination today. To my mind, it’s a symptom of what sociologists describe as an atomized society, one in which isolated individuals pursue only their selfish interests. Maybe our feeling that we’re forced to rely only on ourselves, that we can’t expect solidarity and support, fuels a desire to see ourselves reflected in the literary accounts of equally isolated individuals? Moreover, the women writers, in particular – see Cusk, Ernaux, Levy, and Sheila Heti – broach a tangled set of social issues that’s an urgent concern for many (heterosexual) women today: torn between professional ambitions, difficult marriages, and maternal duties, the characters in their books navigate their life crises without social support. A growing body of literature offers poignant descriptions and analyses of the pressures weighing down on women. If this concern was largely absent from the works of 20th-century women writers, from Katherine Mansfield to Ingeborg Bachmann, that was surely in part because most of them chose (and for good reason) to remain childless and so weren’t especially concerned with the specific challenges of balancing the demands of work, children, partners, and society’s body standards and expectations.

Angelika Kauffmann, „Louisa Hammond“, ca. 1780

By pure coincidence, I recently stumbled across another primal scene of autofiction that I wanted to tell you about: Paul Nizon’s Das Jahr der Liebe (1981). If you can overlook the somewhat objectionable libertinage of his writing (his views on women’s bodies, for example, are irredeemably sexist), the book is a prime example of the metafictional “reflection on the scene of writing,” as you’ve aptly put it. What he does is suggest to the reader that she’s an eyewitness to the process of writing, as though she were with him in his study: “And so I sit down in front of the typewriter, fix my mind on something that, in the course of the day, I retrieved from the tepid gray flows of my time and, as it were, put into safekeeping in my waistcoat pocket, then I condition myself as though in preparation for a long jump, or rather: a steeplechase, I focus on the start and plunge myself into the machine, blindly, in a single bound, my sole intention being to land.” [13] The athletic metaphors romanticize the process of writing as a kind of physical challenge, a spirited attempt to surmount an obstacle. Nizon’s ideal of “writing blindly” or “writing as a warm-up exercise,” which harks back to the Surrealist technique of écriture automatique, is another thing that I think books by contemporary writers like Heti, Nina Lykke, Ben Lerner, or Maggie Nelson bring back in updated form. In a variety of ways, their texts similarly make us believe that the author simply sat down at the typewriter, started somewhere, and let it flow. Their literary productions, like Nizon’s, pretend to be “in the making,” and so it feels like we’re privy to the circumstances in which the writers live and work. In celebrity culture, such illusions of intimacy, here created by means of literary technique, are generally in demand and (usually) rewarded. But perhaps the explanation for the ascendancy of autofictional literature is more simply that virtually everyone is now an online writer, presenting and (ostensibly) revealing himself or herself through words, and so there’s an urgent need for models to guide us on how to handle these formats?

Love, Isabelle

Dear Isabelle,

reading your reply, I’m struck again by how permeable the boundary between life and work that various avant gardes labored to dismantle has now become, and not only in autofiction; permeable in a way that artists and writers back then couldn’t have imagined in their wildest dreams (or nightmares). Like you, I think it’s obvious that today’s digital culture has contributed to this shift, especially through its impact on celebrity culture – but what exactly has that impact been? Star cults and celebrity culture, after all, have been thriving for much longer, in literature as elsewhere: many historians single out Lord Byron as the archetypal example, who, the story goes, woke up one morning in 1812 and found himself famous – the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage had become a bestseller in just a few days. [14] It’s hardly a coincidence that Byron is considered a leading figure of Romanticism, a literary movement whose stated purpose was to fuse life and work, and Byron’s Childe Harold (like Goethe’s Werther) was indeed “an amalgam of character, narrator, and author.” [15] The “Byromania” unleashed by this autofictional text avant la lettre also had media-historical reasons not dissimilar to those we see now: it was facilitated by the popular press and the democratization of a literary culture that was previously the exclusive preserve of the educated classes and aristocracy (a closely related second development was the establishment of authors’ rights, which endowed authorship with the cultural cachet it still has today; the other side of this coin is the author-as-brand-name).

“Democratization” is of course something that digital social media are widely credited with, thanks to their promise of participation for all. And when you look at phenomena like micro-, DIY-, or “accidental” celebrities, it’s hard to deny that the field of the kind of public visibility that’s perceived as “celebrity” has been drastically restructured (from “fifteen minutes of fame” to “famous to fifteen followers,” though some YouTube stars have parlayed a small but devoted following into an audience numbering in the millions). But what strikes me as illuminating for our present concern is the fact that, on social media, micro-celebrities and megastars use the same platforms as us “normal people” – which implies that “democratization” is effected not least by the expansion of the imperative to be visible. As a consequence, we’re all under pressure to devote a lot of energy to cultivating our public image, promoting ourselves: structurally, our situation resembles the one that, in traditional star culture, was reserved for public figures well known for an œuvre that existed beyond themselves (film, music, etc.) and their publicity departments. So as we’re busy constructing our online personae on a daily basis, it’s nice to have paragons to emulate (and stars, needless to say, have always made perfect paragons).

I think it’s crucial here that the rise of the digital economy also entails a renegotiation of the distinction between public persona and private life, which has long been central to the construction of the star’s image in celebrity culture. That’s partly why gossip plays such a vital role in traditional star worship: by intimating undisclosed knowledge about the star’s private life, it comes with the promise of shedding light on what he or she is “really” like (and the general awareness, even among fans, that such glimpses behind the scenes are hardly ever unstaged, as any “exclusive profile” illustrates, is no obstacle to this desire for authenticity; it rather allows for speculations about the details of the staging, always of course with a connoisseur’s nonchalance). This brings us back to what you’ve mentioned as the resource called “life”: as Richard Dyer – who you might describe as a bit of a star in the field of Star Studies – already pointed out with regard to film stars, there is a nexus between the star cult and the indexical quality of photographic, or more generally, audiovisual media: it makes quite a difference if the appearances and stories can be attributed to a body that continues to exist beyond the staged reality (after the closing credits have rolled). [16] Thinking about this makes me realize that, for several years now, whenever I read something that doesn’t leave me cold (either because I loved it or because I resented it), whether autofictional or not, even academic writing, I routinely run a Google search, including images, on the author (most recently, given my own struggle with balancing career and family, I’ve often also found myself wanting to know whether they have kids …).

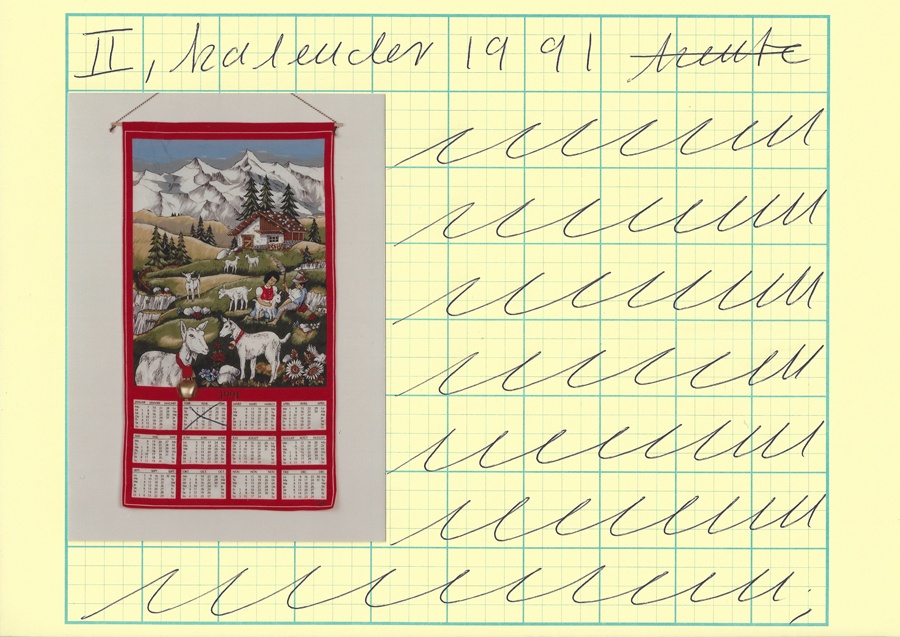

Hanne Darboven, „Mickykalender I–XII", 1991, Detail

Maybe the availability of such information online means that we tend to read all texts as virtual romans à clef, even in the absence of formal devices – first-person narrative – or paratexts that explicitly encourage us to draw connections to the author’s life: if the clues aren’t handed to us, we’ll go hunting for them. For instance, before I even started reading Angelika Klüssendorf’s novel Jahre später (2018), I knew that it was in part “inspired by her marriage to Frank Schirrmacher.” There’s nothing in the book to suggest as much. Yet even reviewers who reject autobiographical (or “indexical”) readings can’t help hinting at the fact that the character of Ludwig in the book may be based in part on the real-life Schirrmacher, a celebrity cultural critic. [17] And of course I promptly Googled interviews with the writer because I wanted to know what she had to say about this interpretation … With someone like Knausgaard, there’s effectively no need to Google, which has surely contributed to his status as a literary superstar.

So I guess that autofiction certainly also caters to the desire among the cognoscenti for “highbrow gossip.” Interestingly, alongside the rise of autofiction, digital celebrity culture has seen the advent of a kind of “auto-gossip”: instead of waiting for paparazzi to snap unauthorized and “unflattering” pictures, today’s celebrities just pick up their cell phone cameras themselves and post their private pictures, “no make-up,” online. I’d be curious, by the way – also because digital culture means there are lots of pictures in play – what the equivalent of autofiction in visual art would be. Moyra Davey comes to my mind, though perhaps mostly for her interest in books … I’ll leave it at that. I’m curious to hear what you think –

Love, Brigitte

Dear Brigitte,

I’m sorry it’s taken me a while to write … In visual art, I think, the boundary between life and work was fairly permeable even in the early modern period, for reasons that had to do not just with the history of media, but also with the way value gets ascribed. Giorgio Vasari’s Vite (1550), for example, contain plenty of “highbrow gossip,” in the form of anecdotes about the artists being portrayed (all of them men) that supposedly encapsulate their demeanor or wit. Description of the art and biographical account blend into each other. The legends that Vasari spun have since formed a kind of transparent veil over the works, bolstering their credibility and thus their symbolic value.

Later on, in the early 20th century, it was, as you’ve noted, the historical avant gardes that were invested in an emphatically close nexus between life and work, also as an emancipatory project; it was seen as progressive to translate art into life. Since the 1960s, by contrast, references to life in visual art have been seen in a different light. Given the new technologies of power (what’s often discussed as “biopolitics” or, in the Foucauldian tradition, as “biopower”), technologies that home in on our everyday practices and our personalities, i.e., our affective lives, mining life for art, can no longer be considered an essentially innocent or, for that matter, progressive practice. When it’s life itself that’s literally going to work, as I once put it with a view to Warhol’s Factory, that necessarily shifts the terms of the discussion around works of art that are (or appear to be) saturated with the resource that is life. [18]

You’ve asked about “autofictional” strategies in visual art comparable to those in literature. Off the top of my head, I can think of three exemplary artists of the 1960s and 1970s: Dieter Roth, Hanne Darboven, and Anna Oppermann. Their autofictional procedures likewise consistently gesture toward the particular media-historical conditions that make them possible. In Roth, self-invention and the work of art coincide; see his late video installation Solo Scenes (1997–98), with numerous screens showing footage from cameras that recorded him around the clock, surveillance-style, as he went through alcohol withdrawal, including when he slept or ate. Oppermann’s Ensembles turn on a magical aspect of the objects that she’d touched or lived with and that appear piled up like relics in a kind of shrine. The works reveal how her I is mediated by things she used or collected. And in Darboven, the I that can be glimpsed in her works was recognizably formed by print media as well as by institutions such as the school system, with its disciplining emphasis on cursive handwriting.

As to autofictional techniques in visual art today, we probably need to draw a basic distinction between artists like Francis Stark or Josef Strau, whose works evince a decidedly literary dimension and come with relevant texts, and others who rely on various aesthetic devices to let their fictional and putatively authentic “self” show through: Henrik Olesen’s most recent work comes to mind. But then it’s important to remember that we obviously encounter visual art on very different terms – in public and/or commercial spaces – whereas the act of reading typically takes place in a more private and secluded setting. So there’s a greater intimacy to how we engage with our books (or the texts on our Kindle screens) that lets us feel like we’re entering into a personal conversation with the authors, even more so when they operate in an autofictional mode. Maybe our need for such direct contact in a sheltered setting is so strong right now because our professional and private lives tend to exhaust our capacity for social interaction? Maybe reading an autofictional life story lets us get back in touch with ourselves, as though finding the I that we’ve lost sight of in the other I of the author? The correspondence format that we’ve chosen for this exchange of ideas has proven well-suited to such an inclusion of the other in a rich tradition that goes back to Marivaux’s Life of Marianne (1731–45). Any letter “contains” its addressee, which lets it negotiate the writer’s as well as the recipient’s social circumstances in a relatively sheltered space. Seen from this angle, it’s hardly a coincidence that Ta-Nehisi Coates chose to frame his fantastic book Between the World and Me (2015) as a series of letters to his son, meant to prepare him for life in a society whose basic fabric is steeped in racism.

Love, Isabelle

Dear Isabelle,

now it’s I who am responding after a considerable delay. Blame it on the usual flurry of urgent tasks and the perpetual multitasking, but also on a talk by Édouard Louis that I heard last week and that really gave me pause. [19] I went there with a certain skepticism because, as you know, however much affinity I feel for anyone who’s moved from one class to another, there’s something I’ve had a hard time forgiving Louis and his friend and mentor Eribon for: to my mind, they haven’t tried to devise a mode of writing that would make their work accessible to the people and relatives they describe – or if that’s asking too much: at least reflect on the fact that they’re turning the lives of others no less than their own into writing. At bottom, this is the old charge of treason, though now with a literary or, more properly, linguistic-political twist: it seemed to me that they (unlike, notably, Ernaux) in a sense presuppose the illiteracy of the people they portray (who would, in any case, never read the books) – that the language in which these newly minted bourgeois examine their social advancement effectively seals their repudiation of the place they come from …

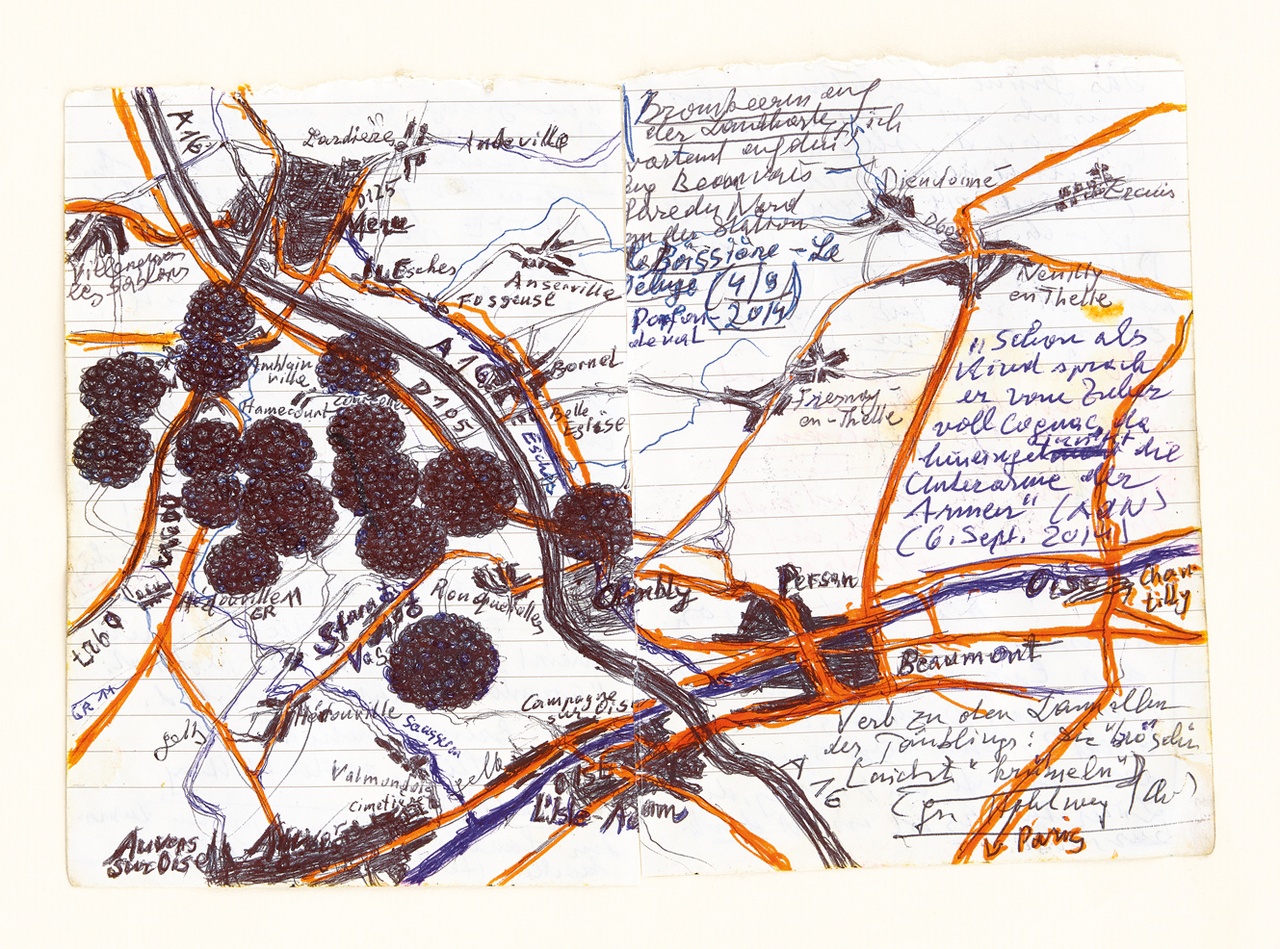

Peter Handke, „Brombeeren auf der Landkarte“, n. d.

But Louis convinced me that his “transformation” was not the result of a choice but of an escape, also from homophobia, of course, and that those who call on him to speak for his class (of origin) are ultimately always trying to put him back in his (former) place. That really hit home – and it made me see an analogy with the precarious speaker’s position from which women and people of color operate in the field of autofiction. Claudia Rankine, for instance, whose acclaimed Citizen: An American Lyric (2014) was widely read in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement, reflects on today’s identity-political interventions by sketching the conflict between a (black or white) “historical self” and an individual “self self,” [20] which adds several layers of complication for the position from which a black woman writes. In a similar perspective, Ta-Nehisi Coates, although not exactly defending the Trump supporter Kanye West, pointed out the burdens that come with being a black celebrity: if society at large forever regards Kanye as an “example of his kind” and holds him responsible for his entire community, so does that community – as it did with Michael Jackson before him: “And we suffer for this, because we are connected. Michael Jackson did not just destroy his own face, but endorsed the destruction of all those made in similar fashion.” [21]

Needless to say, in taking a less dim view of Louis – I’d previously dismissed him as mostly a drawing-room revolutionary, primarily on the basis of his public image as a celebrity and especially after I’d seen the photographs of the trio Louis-Eribon-Geoffroy de Lagasnerie [22] – I was certainly taken in by a strategy of authentication. Or, then again, the commitment with which he spoke persuaded me, because at the end of the day, such statements do succeed in sharing something and confronting listeners, most of whom are presumably members of the “dominant class,” with a world that’s become disconnected from theirs. As he was speaking, I was even convinced of his rather pointed claim that that class must expend an enormous amount of psychological energy on the self-delusion required to block out the fact that voting for the Right (or even: not voting for the Left) means being complicit in the killing of migrants.

Now that I’m putting it to paper, that does strike me as laying it on a bit thick. Still, let me for once take our epistolary format as license to indulge in the confessional mode myself: for the first time in a long time, I’m cautiously hopeful – a sentiment bolstered by rereading En finir avec Eddie Bellegueule (2014) after the lecture – that something like a “committed literature” is possible: a literature that doesn’t get tangled up in aporias or lose its way between the dreary alternatives of activist sloganeering for the converted and a Kafkaesque or Bartleby-style refusal to engage. [23] Now, this sense of urgency in the engagement with reality, which, exactly as you say, encourages the reader to “get in touch” not just with herself but also with other lives, with the lives of others, is surely not a universal quality of today’s autofiction – for instance, I don’t see it in Knausgaard, the trend’s poster boy. Which may be yet more evidence that “autofictionality” isn’t anything more than a catchall term used to lump together works that are so different that progressive politics can hardly be regarded as their common denominator. Still, there are examples of autofictional writing that deftly short-circuit the I with the society in which that I articulates itself, and then the sparks fly … To be continued, I hope!

Love, Brigitte

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Notes

| [1] | It’s telling that, in all the years since Texte zur Kunst was launched in 1990, there hasn’t been a single issue devoted to literature, though we’ve occasionally run interviews with writers like Rainald Goetz. See “Wie bist du denn drauf? Ein Interview mit Rainald Goetz von Isabelle Graw und Astrid Wege,” in: Texte zur Kunst 28, 1997, pp. 39–51. Of course, I still followed contemporary literature, like Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, which I read right when it came out (in 1997). I remember being both fascinated with and upset by her flirtation with the pose of female masochism – and, later, Navid Kermani’s inspiring Dein Name (2011), also a project in the domain of autofiction, though its narrator is, as Diedrich Diederichsen put it, “relational,” which is to say, characterized by his social ties. See “Die besten Bücher des Jahres 2011,” https://www.sueddeutsche.de/Kultur/geschenke-in-letzter-minute-die-besten-buecher-des-Jahres-2011. |

| [2] | Fredric Jameson has aptly described Knausgaard’s technique as “itemisation.” See Jameson, “Itemised,” in: London Review of Books, vol. 40, 21, 2018, pp. 3–8. |

| [3] | Kushner also writes for Artforum, so she’s at home in the art world. Lerner is an academic by trade, and his work is read in art circles. Moshfegh, too, is personally associated with several members of the social milieu of the visual arts. |

| [4] | Deborah Levy, The Cost of Living: A Working Autobiography, London 2018. |

| [5] | See, for example, Alex Clark, “Drawn from Life: Why Have Novelists Stopped Making Things Up?,” https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jun/23/drawn-from-life-why-have-novelists-stopped-making-things-up. |

| [6] | See the exhibition project “Hubert Fichte: Love and Ethnology,” organized by Diedrich Diederichsen and others: https://www.projectfichte.org. |

| [7] | This is how Didier Eribon characterizes himself: as a “‘class traitor’ […] or a ‘renegade’ […] whose only concern, a more or less permanent and more or less conscious one, was to put as much distance as possible between himself and his class of origin.” See Eribon, Returning to Reims, London: Penguin UK, 2018. The translation of “refuge de class” as “class traitor” seems somewhat exaggerated for what might better be translated as “defector.” |

| [8] | Christian Lorentzen, “Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin: How ‘Auto’ Is ‘Autofiction’?,” https://www.vulture.com/2018/05/how-auto-is-autofiction.html. On Doubrovsky’s practice and theory and the history of autofiction in a narrower sense (before its current renaissance, which apparently escaped the author’s attention), see Claudia Gronemann, “Autofiction,” in: Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction, vol. 1, Theory and Concepts, ed. Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf, Berlin 2019, pp. 241–46. |

| [9] | See Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Confessions (1782), trans. Angela Scholar, Oxford 2000, p. 5. |

| [10] | See Jean-Paul Sartre, The Words, trans. Irene Clephane, London: Hamilton, 1964. |

| [11] | Ibid., p. 49. |

| [12] | Ibid., p. 133. |

| [13] | See Paul Nizon, Das Jahr der Liebe, Frankfurt/M. 1981, p. 30. |

| [14] | Loren Glass, “Brand Names: A Brief History of Literary Celebrity,” in: P. David Marshall/Sean Redmond (eds.), A Companion to Celebrity, Malden, Mass./Oxford 2016, pp. 39–57, esp. p. 39. |

| [15] | Ibid., p. 38. |

| [16] | “Joan Crawford is not just a representation done in paint or writing – she is carried in the person née Lucille Le Sueur who went before the cameras to be captured for us.” Richard Dyer, “A Star Is Born and the Notion of Authenticity” [1982], in: Christine Gledhill (ed.), Stardom: Industry of Desire, London/New York 1991, pp. 132–40, esp. p. 135. |

| [17] | “Reading novels as autobiographical is a philological taboo. And yet no reader is so above human affairs that she would not look for the substratum of real experience behind characters in a novel. It is a well-known fact, and mentioned in her Wikipedia entry, that Angelika Klüssendorf was married in the 1990s to Frank Schirrmacher, the former co-publisher of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, who died in 2014 […].” Ijoma Mangold, “Scheißreich, aber anständig,” https://www.zeit.de/2018/05/angelika-kluessendorf-jahre-spaeter-roman. |

| [18] | See Isabelle Graw, “When Life Goes to Work: Andy Warhol. A lecture delivered at the conference ‘Andy 80?’ at Harvard University,” in: Texte zur Kunst 73, 2009, pp. 124–35. |

| [19] | Édouard Louis, “Changing: On Self-Reinvention and Self-Fashioning,” Mosse-Lecture at Humboldt University, Berlin, June 27, 2019. |

| [20] | Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric, New York 2014, p. 14. |

| [21] | Ta-Nehisi Coates, “I’m Not Black, I’m Kanye. Kanye West Wants Freedom – White Freedom,” https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/05/im-not-black-im-kanye/559763/. |

| [22] | It didn’t help that Louis expressed his support for the Gilets Jaunes movements in rather simpleminded terms in several interviews. |

| [23] | See Theodor W. Adorno, “Commitment” [1962], in: Notes to Literature, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen, vol. 2, New York 1992, pp. 76–94. |