ASSET LOGICS

„TIME in CRYPTO related ART and NFT“, Galerie Nagel Draxler at Square, St. Gallen, 2022, Ausstellungsansicht / installation view

Unlike most art forms, you can’t make an NFT without the market. You might say this is self-evident, and that a kind of market positionality is contained within the name “NFT,” or non-fungible token – and you’d be right. Otherwise, why call something a “token” and refer specifically to its “non-fungibility”? Non-fungible, if the term needs clarification, is finance jargon for “cannot be exchanged 1-to-1 for other assets of the same kind.” Dollar bills, for example, are fungible; paintings (and houses, used bicycles, unpaid debt, etc.) are not. Dollar bills signed by famous artists become non-fungible – yes, you could still use them to buy groceries, but it would be a poor financial decision. Perhaps paintings become fungible again if they are so unwanted they return to their material use-value as kindling and fire starter – or perhaps not fully, since some paint is toxic.

And there’s an interesting point here: fungibility is an abstraction. The apparatus that allows me to believe that my dollar bill can always be exchanged 1-to-1 with your dollar bill is outside of the object itself: it is systemic, a product of a state, a series of institutions, trust, and language. The dollar bill has two lives, one as a symbol and one as an object. As a symbol, it is fungible, 1-to-1-to-1-to-1, “in God we trust.” [1] But as an object, my cotton-linen paper dollar bill was printed in 2001, it has a coffee stain on the left corner, and someone doodled the poo emoji on it in blue ballpoint. Yours was printed in 2019 and should still be crisp, but you’ve been carrying it rolled in your wallet for half a year now, using it to do cocaine because you found it on the side of the road and convinced yourself it was lucky. Artworks, with their claims of aura, of the precious hand of the artist, have their own symbolic projections, but they have more in common with the lucky dollar bill than the normal one. Non-fungibility is the ur-state of “things”; they come into the world first as non-fungible. Fungibility depends on the symbolic apparatus of the state.

Late Uruk tokens aus / from Tell Brak, Syrien / Syria, ca. 3350– 3100 BCE

There is evidence from the ancient Mesopotamian city of Uruk, where archaeologists found some of the first known records of accounting, that at first a method called “correspondence counting” was used, which required no knowledge of numbers. Instead, clay tablets in the shape of the thing being counted were used, and the counter could check whether they “corresponded”: five clay tablets shaped like loaves to count five loaves; eight tablets shaped like jars to count eight jars. [2] The abstraction of the pure number independent of the thing being counted came later. And this is to say there is some irony, and perhaps a site of reflection for how deep and how far the machine of abstraction has traveled, that in the blockchain world, unlike the real one, fungible tokens were invented first.

But that is beside the point. The point is that placing something – some kind of digital image or artwork – into the framework of an NFT, or perhaps in adjacency to the blockchain generally, hails it as an asset, entering into a financial relationship with other assets. In other words, into a market. This has been stated well in other places, most eloquently by A. V. Marraccini in Artforum, who writes that through the “wrapper of the smart contract, all NFTs become a kind of performance of exchange.” [3] But when I say that “you can’t make an NFT without the market,” I don’t mean this strictly, or even primarily, in the ontological sense. I mean this much more literally. Simply creating an NFT will result in its appearance on a marketplace website. We can speak about markets intangibly, as an arena with an indefinite border where things are bought and sold and where anything that can be priced may potentially enter it, but there is also the far more tangible NFT marketplace, which is a website.

The subset of non-fungible things we’re calling NFTs are stored on a blockchain. In fact, that’s what an NFT is, in its most distilled form: it is a kind of smart contract, which is blockchain-specific code that corresponds to an agreed-upon standard template. In the case of Ethereum, the relevant standard is called ERC-721. [4] Any NFT that appears on any marketplace website also has a corresponding smart contract, which must conform to such a standard. Most people who create NFTs do so directly through the interface of a marketplace website: click, click, upload a JPEG, click, click, done, and this layer is invisible to them. But there are other ways to create an NFT, including interacting with the blockchain directly, without the marketplace as an intermediary, using a bit of code to create another bit of code – the NFT smart contract. But here’s the thing: your NFT will soon appear on a marketplace anyway. All the data on the blockchain is public, and anyone can read from it at any time. Big marketplace websites such as OpenSea scrape, display, and list all NFTs, no matter how they were created, without permission or consent from the creator or owner. That permissionlessness is specifically one of blockchain’s core affordances.

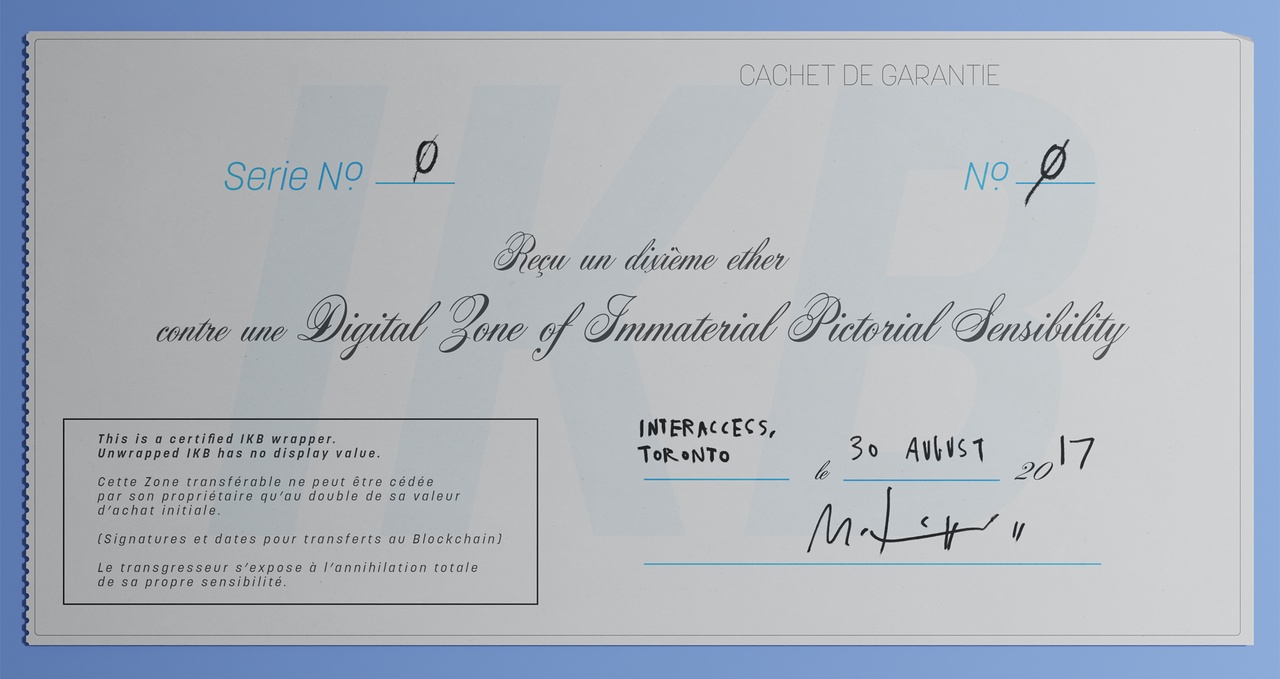

Mitchell F. Chan, „Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility No. 0“, 2017

The NFT is for sale right from its creation – no soft gestation in the studio, no ask-only price list. You don’t have to create a listing. The NFT is visible already, and I can place a bid. Yes, you the creator or owner can hide it, but only after it has been listed in the first place. The market is the default. Most NFTs seem to assume that the JPEG is where the art is, the art is in the image, or in the video, but most NFT marketplaces and the press race to assure us that it is otherwise: the meaning is the price, current bids, sales history, the thrill and bafflement of being confronted by a million-dollar racist monkey picture. [5] This is what they talk about. This is what they show us. But if, as we might say, the market is the massage, where are its trigger points? [6]

It’s impossible to talk about NFTs without talking about their outsiderness – and the way they reveal the process by which money whets the appetite of institutionalization. NFTs often borrow aesthetics from cartoons, video games, renders, or pixel art with a wholehearted and fully literate embrace that the institutional art world seldom manages – but that’s not the source of their outsiderness. It is located more in the tautologies of the institutional theory of art, where things become “artworks” when canonized by the art world – something we cannot define, of course, but we know it when we see it. [7] Many NFT stars have no formal art training or prior experience with the world of museums and traditional galleries. Only after his infamous 69-million-dollar auction success did Beeple begin talking about getting an art history degree. [8] Not to mention collectors-only parties at popular NFT events, or blockchain companies buying out Times Square: spectacles forging a new kind of institutional legitimacy at lightspeed. We can observe, alongside Federico Campagna, “the apparently contradictory fact that there is not one, but countless and potentially infinite ‘centres’” [9] – all of them seemingly available to be decentralized. There is a community of creators and collectors of NFTs who do not know or care about the norms and codes of “contemporary art” – and why should they? Who are you to tell them what the emperor is wearing? It’s not even a conversation. They have their own emperor. His name is Justin Sun. Or maybe punk #-something.

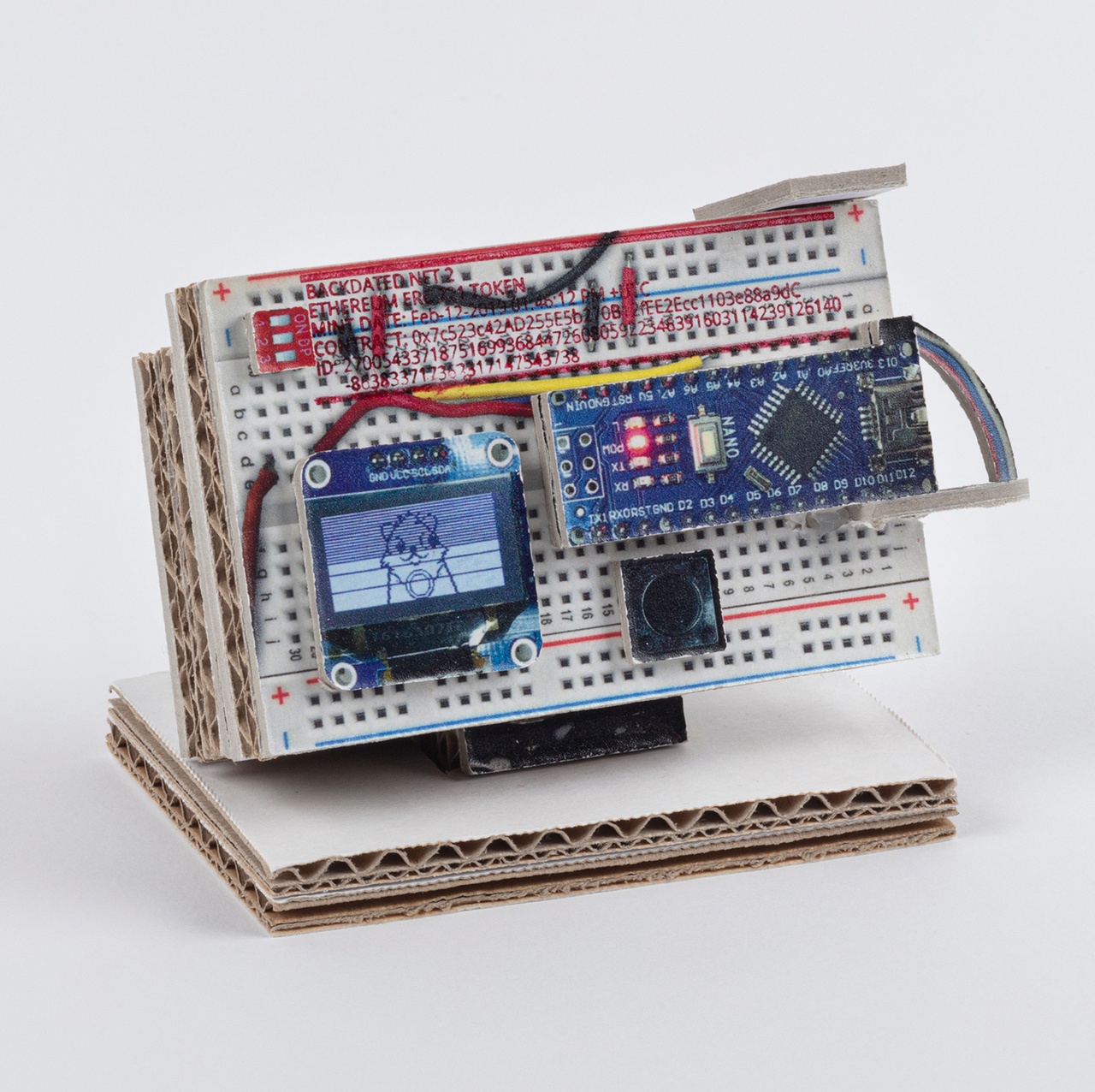

Simon Denny, „Backdated NFT / Cryptokitty Display Hardware Wallet Replica (Celestial Cyber Dimension)“, 2018–2019–2021

Like the forms of the NFT exhibition – where the digital metaverse gallery full of JPEGs, a skeuomorphic white cube, has been superseded by the physical white cube full of wall-mounted televisions – the immediate entry of NFTs into the market has bled over into physical exhibitions, too. Recently, at the opening of a new NFT-related exhibition, I sold my own artworks – no gallery staff, no middlemen. Collectors sent me money in real time, I whatsapped them my Ethereum address, and they left the gallery with the artwork in hand. Even as booth babes are cast out of fairs, artists become them. [10] The pure market speaks. There is an art world that would be horrified by this – but only one of many art worlds. And it is the horrified art world that is eating its edges as fast as possible, now with blockchain co-branded events during Art Basel and several blockchain-sponsored events in Venice during the Biennale’s opening week. As Bataille reminds us, “Extreme seductiveness is probably at the boundary of horror.” [11]

Selling one’s soul is the original forbidden act of putting something sacred and non-fungible into the market. But to recall the process by which 1,000 different pieces of dirty paper become dollar bills and where you, the individual, become human resources, we can ask, Which cog is more central to the engine of capital? Which process of assetization, that of the non-fungible or the fungible, is more violent? In his book Debt, David Graeber contrasts market and human economies, writing, “In a human economy, each person is unique, and of incomparable value, because each is a unique nexus of relations with others.” [12] Of course, with NFTs the distinction may not matter – the soul is for sale from the start.

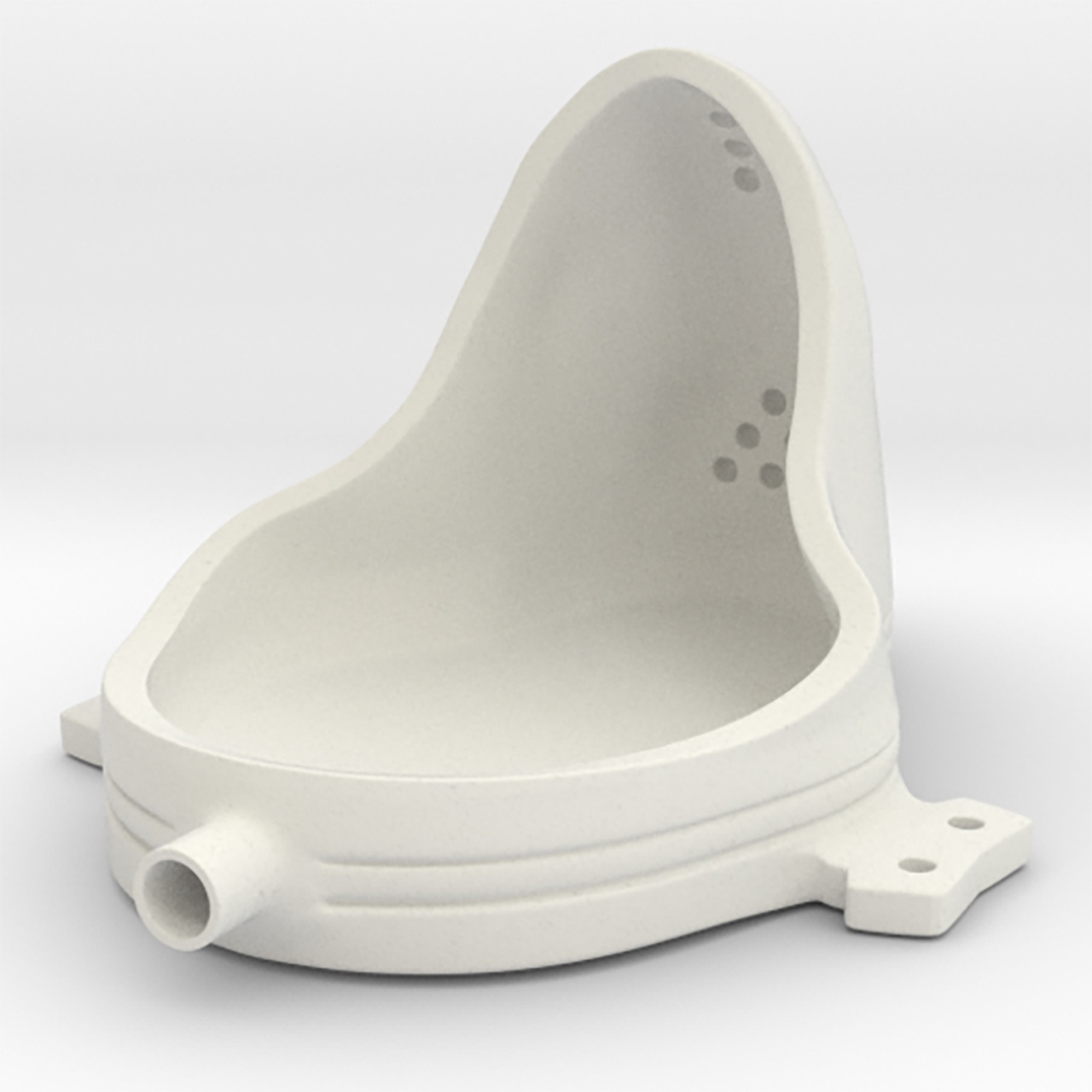

Rhea Myers, „Urinal“ aus der Serie / from the series „Shareable Readymades“, 2011

In a recent conversation between McKenzie Wark and Rhea Myers, Myers, one of the first and best artists in the blockchain world, remarked, “Capitalism enjoys it when you resist, because that’s how it finds new things to enclose.” [13] I’m reminded of the controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis about language: that the structure, grammar, and use of a language shape the perceptions of the world held by its speakers. Is there anything to say with the words of the market that isn’t the market itself? The art world is uncomfortable with the money changers in its church, but God is praying over his dice as he shakes them. In the immortal words of 20th Century Steel Band, “Everyone’s got to make a living. Heaven and hell is on earth.”

Sarah Friend is an artist and software developer, specializing in blockchain, games, and the p2p web. Recent exhibitions include “Off: Endgame” (Public Works Administration, New York), “Worldbuilding” (Julia Stoschek Collection, Düsseldorf), “Proof of Stake” (Kunstverein in Hamburg), “Breadcrumbs” (Galerie Nagel Draxler, Cologne), “Proof of Art” (OÖ Landes-Kultur, Linz), and “Panarchist Dinner” (Floating University, Berlin).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy Galerie Nagel Draxler, photo Julia Maja Funke; 2. Tell Brak project 2001, photo Jack Cheng; 3. Courtesy of the artist; 4. © Simon Denny, courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz; 5. 3D printable digital model by Christine Webber, commissioned by Rhea Myers

Notes

| [1] | “In God we trust” is the official motto of the United States and appears on its currency. |

| [2] | Tim Harford, “How the World’s First Accountants Counted On Cuneiform,” BBC World Service, June 12, 2017. |

| [3] | A.V. Marraccini, “Ethereal Presence: NFTs and the Theater of Risk,” Artforum, June 16, 2022. |

| [4] | William Entriken, Dieter Shirley, Jacob Evans, and Nastassia Sachs, “EIP-721: Non-Fungible Token Standard,” Ethereum Improvement Proposals, no. 721, January 24, 2018. |

| [5] | The Bored Ape Yacht Club, a large and well-known NFT series, was called out by artist Ryder Ripps as potentially having encoded racist messages. See Dorian Batycka, “Artist Ryder Ripps Called the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs Racist. Now, Yuga Labs Is Suing Him for Trademark Infringement and Harassment,” Artnet News, June 29, 2022. |

| [6] | Marshall McLuhan, The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects, produced by Jerome Agel (Corte Madera, CA: Gingko, 2001). |

| [7] | Justice Potter Stewart, in the famous 1964 Jacobellis v. Ohio verdict on whether the state of Ohio could, in accordance with the First Amendment, ban the showing of Louis Malle’s film The Lovers (Les amants), stated the following: “I have reached the conclusion […] that under the First and Fourteenth Amendments criminal laws in this area are constitutionally limited to hard-core pornography. I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.” |

| [8] | Jason Farago, “Beeple Has Won. Here’s What We’ve Lost, New York Times, March 12, 2021. |

| [9] | Federico Campagna, Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), 166. |

| [10] | “Booth babes” are models, usually women, hired by conferences to attract more visitors to their trade fair booths. Recently there has been a push to end the practice of hiring them. |

| [11] | Georges Bataille, Visions of Excess: Selected Writings 1927–1939, trans. and ed. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985), 17. |

| [12] | David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years (New York: Melville House, 2011), 158. |

| [13] | “Conversations: Rhea Myers and McKenzie Wark,” moderated by Brian Droitcour, Outland, February 25, 2022. |