From the perspective of value theory, Isabelle Graw examines the art historical moment in the early 1960s when sculpture was transfigured into object. Yet, as Graw illustrates with two works from 1961, these objects nevertheless remain “specific objects” (Donald Judd). She argues that by evoking the presence of various traces of artistic labor within them, both works reveal the specific value-form of the art object. However, according to Graw, the central ideological operation of the art object is made tangible in Piero Manzoni and Robert Morris to the same extent that it is also foiled.

PROPOSITION.

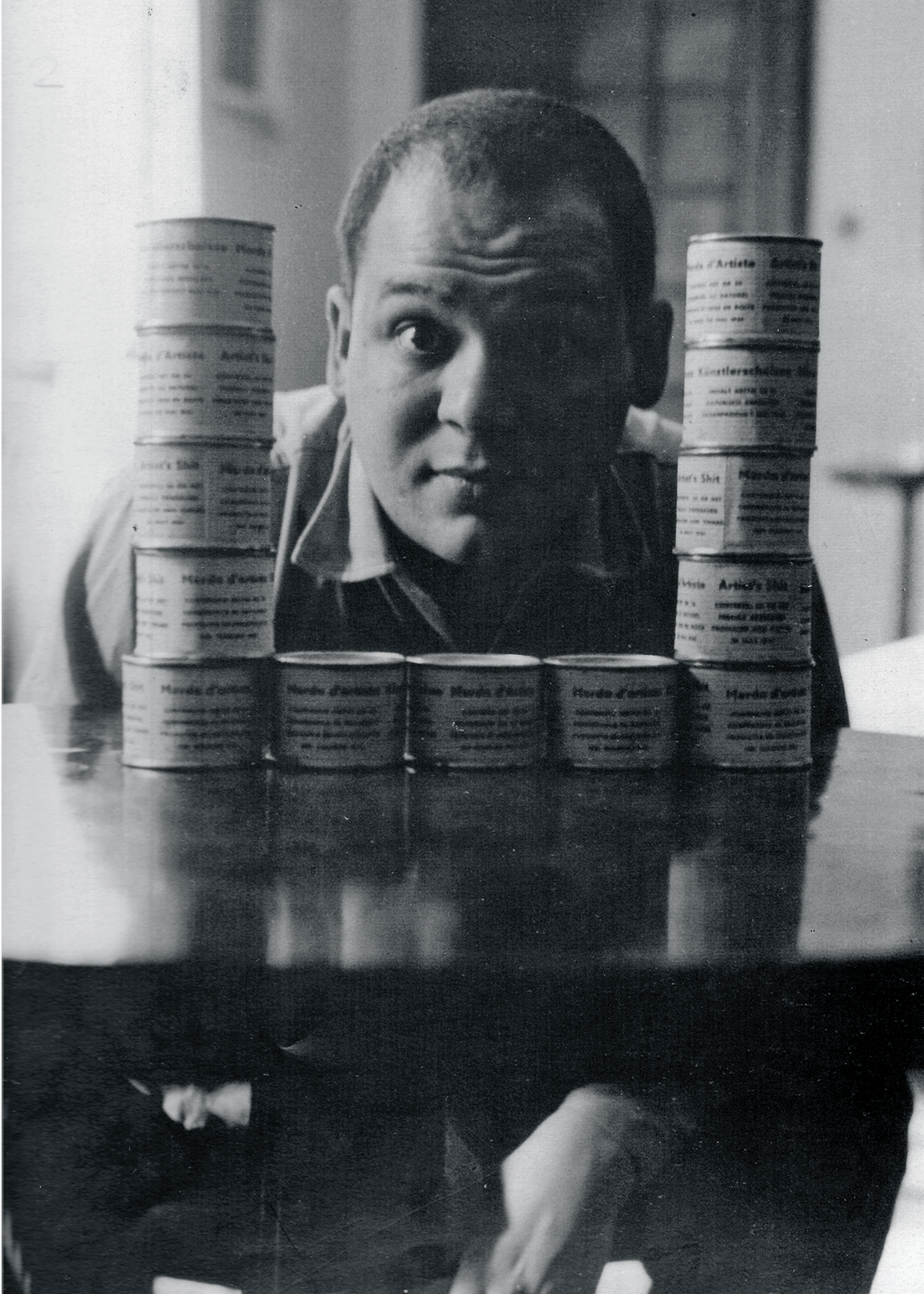

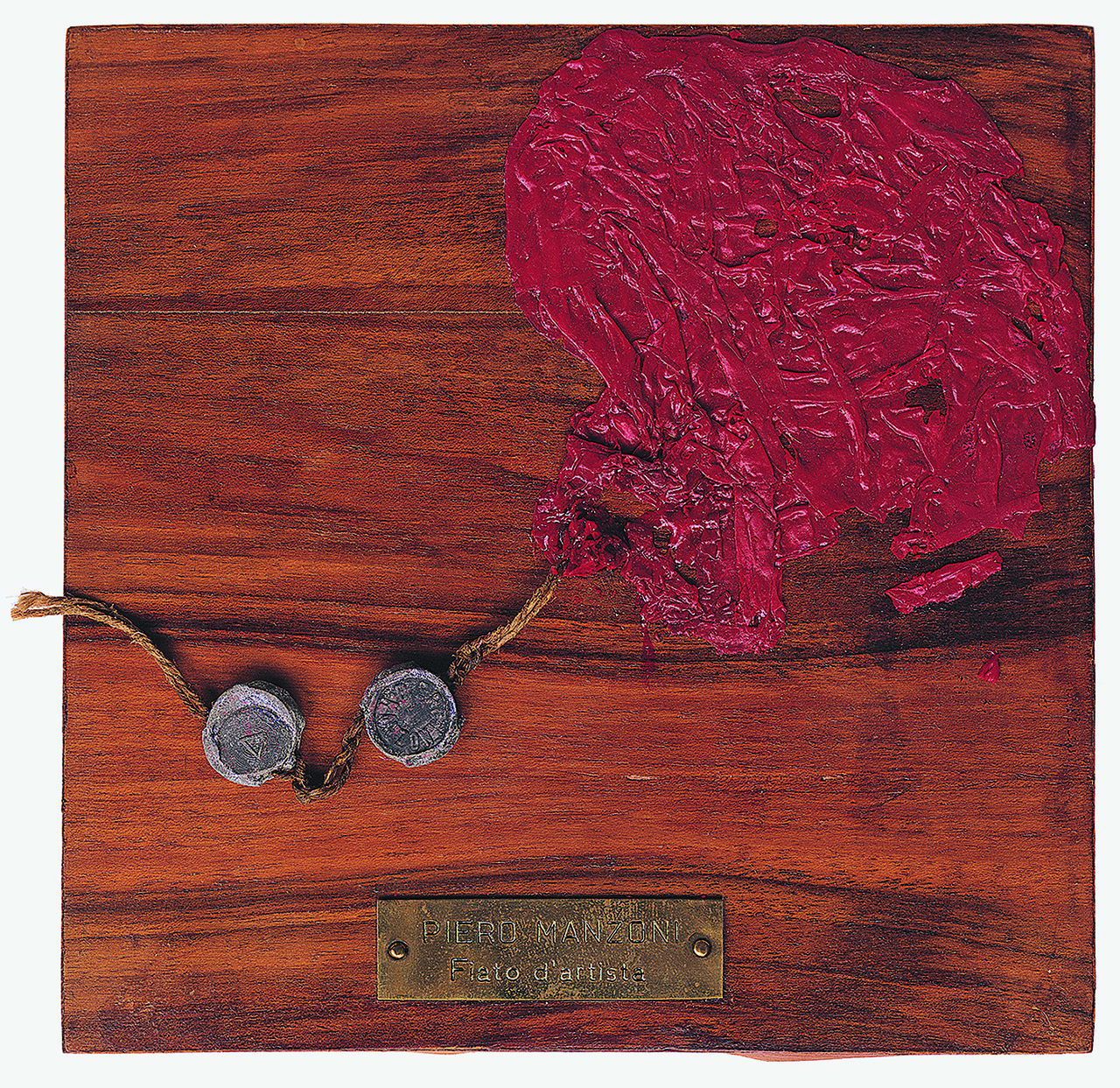

In the following, two works from 1961 – Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista and Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making – serve as objects in a value-theoretical demonstration. Manzoni’s Merda d’artista consists of 90 cans, said to have been filled by the artist with his own excrement. Morris’s sound box is a cube made of walnut wood, through which a recording of the sound of the box’s own making can be heard. Both of these works, in their different ways, create the impression of containing traces of the artist’s physical labor, or of their digestive process. After all, the body is “at work” during defecation, hence the metaphor of “doing one’s business.” For the psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster, expelling feces from our bodies every day is a form of labor. Against this backdrop, I will illustrate how Manzoni’s cans and Morris’s box both preserve the trace of work processes. I argue that these two artworks not only demonstrate the factors underlying the specific value form of the art object but also present them in an exaggerated and humorous way. From a value-theoretical perspective, this strong connection between the art object and its creator’s work process – pointedly emphasized in both Morris’s sound box and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista – is what makes the work of art the specific kind of commodity it is.

Ordinary commodities, or commodity fetishes, as Karl Marx called them, abstract from the concrete labor that has been expended on them, thus concealing this labor, rendering it invisible. By contrast, the pieces by Morris and Manzoni conjure up the presence of precisely this production context and the physical work process, enabling them to present themselves as commodities of a specific kind. Morris allows acoustic traces of his work to emerge from the interior of the sound cube, while Manzoni fills the cans with the physical result of his process of bodily excretion. In both of these cases, rather than the work process being disguised, as with the commodity fetish, it is indicated to be present in latent form. The narrow reduction of artwork to commodity fetish, as in Theodor W. Adorno’s reflections on artistic labor, is clearly inadequate here. This is because, although Adorno claimed autonomy in art was only possible with the concealment of labor, Manzoni’s and Morris’s works in fact show the opposite: the possibility of the process of artistic labor becoming tangibly present within the art object itself.

The fact that art objects, such as cubes or cans, are especially suitable for such value-theoretical demonstrations can be attributed to the interior space created by their three-dimensionality. I argue that the presence of this interior space can promote the suggestion of an inner animation, something crucial from a value-theoretical perspective. But I also work out the ways in which auxiliary aspects – including signatures, limited editions, and the production of the artist’s legend – can help to underwrite these works’ particular value-form. I outline how Morris and Manzoni respond to the specific constraints presented by an emerging media society through these and other works, which are also marked by the personal. I regard Manzoni’s cans, in particular, as the seismographs of a shift in the reigning value system that would take place somewhat later, after the demise of the Bretton Woods Agreement (1973). Although I suggest the cans and Morris’s sound box succeed in inciting the viewer’s desire for there to be a person within the product, I ultimately show how they disappoint and counteract this desire. It is precisely because these objects withhold something from us that they hold such considerable potential for fascination.

1. MORRIS’S SOUND BOX AND MANZONI’S “MERDA D’ARTISTA” ARE OBJECTS OF A SPECIAL KIND.

Morris’s box and Manzoni’s cans exemplify sculpture’s paradigm shift in the 1960s and 1970s, marking the transition from sculpture to object, a development that was particularly characteristic of Minimal Art. Around this time, the term object was applied to sculptural works of art, above all as a way of clearly differentiating minimal objects from sculptures and paintings. Donald Judd described the works of Minimal Art as “specific objects” – having a specificity he primarily attributed to their constitutive materials, such as steel or metal. This, in my opinion, serves as evidence of the need, felt even back then, to emphasize the special status of these objects. Although their serial nature meant they were aligned with the industrial production of “ordinary” goods, they nevertheless remained objects of a special kind, which Judd accordingly described as “specific.” From a value-theoretical perspective, what is interesting in this context is that Judd furthermore located the specificity of minimal objects in their three-dimensional character. This three-dimensionality creates “actual space” that is “intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface.” Judd’s emphasis on three-dimensionality thus sought to assert the superiority of the minimalist object over the painted image. For Judd, the power of this object comes from its suggestion of an “actual” and “powerful space.” Such a space could be said to exist in both Morris’s sound box and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista cans, where it is foregrounded and “filled” in a emphatically “actual” and “powerful” way.

Like Judd, Morris always emphasized the three-dimensional character of his minimalist works, characterizing them as “process type objects” – that is, objects that not only result from a process but that incorporate this process into themselves. Morris praised the painter Jackson Pollock for incorporating the process into his final product, but he considered the interior space in Minimal Art’s three-dimensional objects to be even better suited for the preservation of process. With Box with the Sound of Its Own Making, Morris seems to have taken this idea to its extreme. Through its integration of sound, the box also violates modernism’s law of purity, with previously separate fields of music/sound and sculpture/object here subject to direct mutual short-circuiting.

Minimal Art’s serial-industrial production methods and the readymade strategies of Pop Art also find resonance in Manzoni’s cans. After all, these are ordinary commercial cans, 90 of them, manufactured industrially, in their form reminiscent of tins of tuna or pâté. The mode of packaging alone emphasizes the commodity character of this work of art. But the labels attached also demonstrate a mimetic orientation toward the aesthetic of the commodity. These labels claim to guarantee that the contents are “authentic,” with “no preservatives” having been added. While adopting the rhetoric of the food industry, Manzoni also signed each individual can: as a result, the cans hover between being standard commodities and unique works of art. Food production companies also attempt to lend their products credibility and a sense of seriousness: for instance, the German brand “Dr. Oetker” refers to its founder’s doctorate. But no one seriously thinks that some part or trace of “Dr. Oetker” is present in his frozen pizzas. However, Manzoni and his cans filled with his own feces do feed this fantasy, which is further fueled by his signature.

3. THE ECONOMY OF THE CAN IN THE 1960s.

It was no coincidence that it was the “can” format to which Manzoni turned. We might, in this context, also think of Jasper Johns’s Ale Cans (1964): this work features two ale cans cast in bronze, thus they are not readymades in the strict sense; they have also been painted on and seem far more sculptural than Manzoni’s cans. In 1962, shortly after Manzoni’s exhibition of his cans, Andy Warhol exhibited 32 paintings entitled Campbell’s Soup Cans at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. Warhol’s images were presented on a kind of supermarket shelf, emphasizing their similar status to commodities. Manzoni’s can serves to contain his corporeal excretions, whereas Warhol’s can is the central figure within an image. One might say Warhol sacralized the can, enhancing its value by portraying it as a sacred object. Manzoni, by contrast, used the can as a container for his shit (rather than food), in this way devaluing and profaning it as an object.

4. THE LIMITED EDITION AS A WAY OF PRESERVING VALUE.

Despite their differences in media and iconography, what connects Warhol’s and Manzoni’s cans is their shared emphasis on their own status as a limited edition. Manzoni always spoke of “90 cans of Artist’s Shit,” while Warhol’s work is often called “32 Campbell’s Soup Cans,” as if the number of these hand-painted works formed an integral part of the work. In both cases, reference to the edition’s limitation ensured that serially produced works could approximate the status of unique works of art, since by definition limitation means their numbers are limited. What’s more, this limitation exists because of a decision made by the work’s author, who in doing so recalls themselves to mind, so to speak. By deciding the size of the edition, the artist brings their own authorship into play. In this context, it makes sense that Morris’s sound box is only available as a very limited edition: there are three exhibition copies in addition to the original, which is now held at Seattle Art Museum. This means that the box is not a unique object. Morris deals with it like a piece produced in a limited edition, reducing its authenticity; it exists as a plural thing but in only three copies, which shifts it back in the direction of uniqueness. And since Morris himself has determined the exact number of copies to be made, here, too, he resonates within his own work, inside these limited-edition sound cubes, as the work’s unique author.

5. ARTISTIC LABOR IS INCREASINGLY SIMILAR TO LABOR IN GENERAL BUT REMAINS COMPARATIVELY PRIVILEGED.

In this context, it is telling that Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making seems not to have been industrially made, as was quite common with the objects of Minimal Art. Instead, the box results, audibly so, from its creator’s (supposed) craftsmanship: Morris claimed to have made it with a hammer and saw in a three-and-a-half-hour process, and the recording of which plays from inside the box. To me, Morris’s box seems to offer symbolic proof that there is something specific about artistic labor, despite repeated attempts, since the 1920s, to take artistic labor closer to labor in general. Artists such as Alexander Rodchenko and, later, Richard Serra portrayed themselves as industrial workers in photographs, whereas the work put into Morris’s box is presented as craftwork or, more precisely, as a combination of manual and intellectual activity, since the box containing the sound of its own making is clearly based on an idea, which the artist then creates manually. The box also reminds us that artistic labor remains a comparatively privileged activity, as opposed, for example, to waged labor. As a rule, artistic labor results in a product with a materially unique character that is still attributed to its creator even when it circulates independently of them.

Since the 1960s, market constraints have increasingly intervened in artistic practice (with fewer and fewer artists able to make a living from their work). Nevertheless, in contrast to waged workers, artists can, largely speaking, determine the subject of their work, as well as their own working hours. Other workers can only dream of such freedom. However, Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making also contains a hint of symbolic identification with waged labor. The tape recording documents the time – three and a half hours – spent making the piece, suggesting the possibility of calculating an hourly wage for the artist, as with waged workers. But at the same time, Morris’s piece also shows that in relation to artistic labor, the actual duration of working time is unimportant. Unlike industrial work, work created in a comparatively short time can also pay very well in the art world. Morris, by making the time spent working on the box into the subject of the work, alludes to the similarities and the differences between artistic labor and other forms of labor.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a Marxist slogan was prevalent among artists: render your conditions of production transparent. Morris’s sound box may seem to align with this, but it does so only on a superficial level. Although the box supposedly contains the acoustic trace of its own production, we ultimately learn little about the nature of the work. The labor that made the box literally remains in the dark: the sealed box makes any direct access to the artist’s working process impossible. It appears solely as an acoustic trace.

6. THE PRODUCTION OF LEGENDS LENDS PERSONALITY TO IMPERSONAL-SEEMING WORKS.

As well as through the signature and the limited edition, the artwork’s specific value-form has traditionally seen its value guaranteed by the production of legends associated with the artist. Since the early modern period, artists’ life stories have been chronicled according to certain narrative patterns, lending greater credibility to their work. You could even say that, beginning in the 1960s, as mechanical and serial processes threatened the close tie between works and authors, anecdotes have been used all the more urgently, precisely in order to repair the formerly tight connection between the two. Warhol was very adept at enriching his works with legends. Thus, he claimed to eat Campbell’s soup every day, lending a personal touch to his apparently impersonal Campbell’s Soup series, creating the impression of a kind of physical proximity. As sculpture expanded and dissolved its boundaries from the 1960s onward, enabling it to be anything ever since, relations between objects and their creators demanded strengthening. Manzoni went particularly far in this respect, claiming to have filled each can with 30 grams of his own shit, sealing them up to be “smell-free.” The supposed content of the cans brings us closer to the artist’s most intimate activities, his physical excretions. Morris also tried to give his sound box a personal aspect, explaining that he used walnut wood because it reminded him of the smell of walnut trees in the yard of his childhood home. In this way, Morris’s choice of materials helps to energize the neutral form of the cube with something personal. Via this personal anecdote, Morris inscribes a biographical subtext into the box, creating the impression that the artist’s personal origin story is materially resonating within this work. We are a long way from Minimal Art’s supposed depersonalization of the work of art.

7. MAKE USE OF THE SUGGESTIVE POTENTIAL OF INTERIOR SPACE.

It is no coincidence that Manzoni’s cans and Morris’s sound cube were created at a time when parts of the New York and Western European avant-garde were breaking away from Abstract Expressionism, the previously dominant belief system. Artists opted for serial industrial processes and readymade strategies in order to undermine the deep connection between the physical artist’s inner body and the painted image, a connection that had been claimed by Abstract Expressionist painters. In particular, the avant-garde now sought to vehemently reject the premises of action painting, as formulated by critics such as Harold Rosenberg. Where Rosenberg claimed that the painted image was inextricably bound up with the artist’s biography, artists associated with Minimal and Pop Art insisted on the impersonal nature of their own process. Rosalind Krauss has argued that minimalist sculpture sought to abandon the impression of a living “interior space,” as was typical of the work of such modernist sculptors as Henry Moore and Anthony Caro. Instead of suggesting that form unfolds from this living interior space, as the modernists had done, the artists of Minimal Art followed an “ordering system” that “came from outside the work.” Krauss claims that this move enabled them to strip objects of their illusionism, their uniqueness, and their privacy. However, Krauss’s account seems to ignore what is at stake in many 1960s art objects and to miss the point of Morris’s sound box and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista cans. Both of these works, in fact, convey the existence of exactly the kind of “illusionistic center or interior” that Krauss suggests has been overcome. Both Morris and Manzoni fill this interior space and even render it more alive. One could take things a step further and say that these objects, thanks to their three-dimensionality, make the spectator mindful of a living inner space and, ultimately, create an indexical trace comparable to the painterly trace. Whereas painters can avail themselves of a large repertoire of gestures that can be read as ostensible traces of their creators, the only device available to the industrially manufactured cube or the Pop Art readymade box is their interior space. And this is indeed what Morris and Manzoni put to use.

In his book Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde (What we see is what looks at us), Georges Didi-Huberman pointed out that there is something human to be found in minimalist objects, contrary to Krauss’s opinion. For Didi-Huberman, the works of Minimal Art have a “latent anthropomorphism”; he also distances himself from the view, held by Krauss and Judd, that minimalism is characterized by a “pure and simple rejection of inwardness.” Instead, he suggests, the interior is precisely what is important in minimalist cubes, although their interiority can often oscillate between fullness and emptiness and should therefore be understood as a “unsettling place.” Against this backdrop, we can characterize both Morris’s sound box and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista cans as “unsettling places.” They make comparable claims – to be filled with the sounds of the manufacturing process or the traces of their creator’s body – but ultimately, in neither case, do we know if this is true. To investigate that claim – by opening the box or one of the cans – would be tantamount to destroying these as works of art. Since the content of these objects ultimately remains in limbo, something unsettling and alarming continues to emanate from them.

9. MANZONI’S CANS AS A SEISMOGRAPH OF CHANGES IN VALUE.

The pricing of Manzoni’s work must also be viewed as an integral part of it. In an interview, Manzoni said that he set the price per can (each of which supposedly containing 30 grams of feces) to correspond to the current daily equivalent of a single troy ounce of gold. By allowing the price to be dictated by fluctuations in the price of gold, Manzoni highlighted not only the structural relationship between art and money but also contemporary parallels between the work of art in its materiality and uniqueness and the qualities of the dollar as a currency, prior to the expiry of the Bretton Woods system in 1973. The dollar had been the global anchor currency, partly secured on the material value of gold, a relation reminiscent of the crucial material dimension that underlies the art object’s specific value-form.

Almost prophetically, Manzoni seems to have foreseen the consequences for the art world of the end of Bretton Woods and the associated free-floating currency exchange rates. After the dollar came off the gold standard while continuing as the world’s reserve currency, works of art came to the foreground as possible objects of speculation, since they are materially based currencies, as the dollar formerly was. The great commercial success of the New York Scull Auction (1973), a sale of contemporary artworks that was strongly opposed at the time by many artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, was clear evidence of this development. For the first time, an auction for contemporary art made high profits. Manzoni’s pricing also seems to have anticipated the fact that the market prices of artworks would become subject to stronger economic fluctuations than ever before. His cans herald the rise of the art object to a speculative investment in the wake of the dollar’s departure from the gold standard; they also point to the increasing arbitrariness of art prices. By determining the price of his cans in an ultimately arbitrary manner, Manzoni also tells us that the price of an artwork cannot fundamentally be justified. Price determination may offer the appearance of plausibility, but it nonetheless remains random.

CONCLUSION.

Although both Morris’s sound box and Manzoni’s Merda d’artista cans suggest that they contain the artist’s labor (Morris) or the product of his labor-like digestive process (Manzoni), in fact, this is precisely what they withhold from the viewer. We have no access to the work itself, only to its supposedly indexical traces. This figure of withdrawal – that something seems present and yet remains absent – is crucial for the art object’s specific value-form. If the work did not withhold the artist and their working reality from us, it would lose its fascination and its disturbing aspect. Thanks to the processes alluded to, art objects suggest that traces of the artist or at least the traces of their labor process are contained within them. But ultimately, they keep all of that from us. They feed our phantasmatic longing for the person in the product while simultaneously disappointing us. For the spectator, conversely, this means remaining engaged with the object – in other words, recipients twist it and turn it to lend it symbolic meaning, which will eventually be transformed into market value. As a recipient, one also does work: the interpretive and theoretical work that enters into these objects – work that likewise resonates within them and contributes to their specific value-form.

Translation: Brían Hanrahan

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020); Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021); and On the Benefits of Friendship (Sternberg Press, 2023).

For legal reasons, some images that accompany this text in the print publication cannot be included here.

Image credit: 1. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan; 2. © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan; 3. Public domain; 5. Photo Michail Kaufman; 6. Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milan

Notes