How To Take In Sculpture Walead Beshty about Jan Timme at Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, November 19 thru December 12, 2005

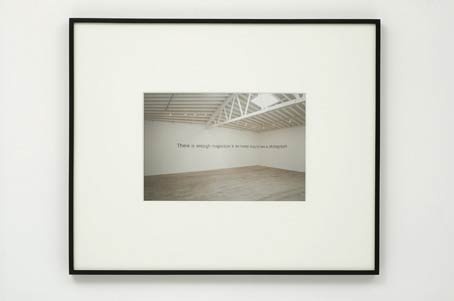

Jan Timme, "Installation shot. There is enough magnesium in the human body to take a photograph", 2005, Installationsansicht "Luft - Air", Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, 2005

Jan Timme, "Installation shot. There is enough magnesium in the human body to take a photograph", 2005, Installationsansicht "Luft - Air", Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, 2005

The initial impression one has of "Luft-air," Jan Timme's solo debut at Marc Foxx Gallery, is that of entering the gallery in the moment of a partial power outage. Dim light spills from the outdoors, guiding your eye past the fluorescent glow of the office, and into the darkened exhibition space where the only thing in view from the entrance is a single candle atop a slender pedestal. As you pass the clutter of invitation cards and artist binders on the front counter into the main gallery, you notice the candle flicker as if troubled by a random breeze, registering your body's disturbance of the air. Your eyes begin to adjust to the murky twilight, noticing the pale distended silhouettes cast across the room by the candlelight striking your back. In the periphery of your vision, a glowing rectangle of daylight focused from the skylight above slinks up the wall. You imagine its methodical voyage, scanning the perimeter of the gallery in a slow meander that repeats daily; you anthropomorphize its movement, imagining Sisyphean boredom. Seeking out its source, you find yourself positioned underneath the skylight you never noticed was there, craning your neck to look up at an image of another pair of feet perched on the edge of shadow. Your surrogate is a hazy video still in muted colors, echoing your own position poised in the gallery's perpetual shadow. Your attention shifts back to your silhouette, which, having centered yourself underneath the skylight, falls upon a single photograph in the corner of the room. As you move in to look, squinting to make out the image, you notice it is a photograph of the wall you're standing in front of, taken at some prior moment when the words "there is enough magnesium in the human body to take a photograph" were there. You're left to consider the fragility and futility of the gesture, and your own body as the raw material of representation, registered in absentia, as it had been moments before in the flicker of the candle's flame, mirrored from above in the video still, and outlined against the very same wall the photographed text once appeared on.

Should you have been distracted from the studied procession of phenomenological listlessness, a reading of the press release will realign your experience. As the text guides you through the spare exhibition, the fragile system of references unfurled amid experiential prescriptions in the first person, you are inclined to agree about your "transformation into a disembodied eye." The resulting experience feels conflicted, if not for the ephemeral preciousness of its immersive detachment, then for its simultaneously experiential aggressiveness.

In Timme's hands, the text on the wall is in its fourth moment of appropriation. Discovered by Timme in the Surrealist journal Documents, edited by George Bataille, it was initially published by a British chemist, then reprinted in the staid Journal des Debats, and finally employed by Bataille as a materialist provocation directed at gestalt humanism (the text itself lists the various raw materials that could be distilled from the human body, the sum total, it surmised would be valued at about 25 francs). [A1] Timme's repositioning outlines a progression from the unity of the self and the body, to the body as material thing, to its final becoming as empty signifier, a dematerialized representation. The text, painted directly into the corner of the gallery and perspectivally corrected to appear flat from the position the photograph was taken, short circuits sculpture's material condition, relegating it to the eventual end point of distribution, the installation view. Here isolated to a single perspective, Timme's gesture seems to parody the dependency of art on the photograph, turning contingent site specificity into decontexualized image in a single gesture, a condition paradoxically implicit in claims for sculptural autonomy (evoking Dan Graham's oft quoted dictum that art doesn't exist until it has been photographed). As critic Michael Fried observed in 1967, having been perhaps the first to identify (albeit derisively) the proto relational contingency evidenced in the program of minimalism, the ideal state of sculptural autonomy is realized in a "…continuous and entire presentness, amounting as it were, to the perpetual creation of itself, that one experiences as a kind of #Kinstantaneousness#K: as though if only one were infinitely more acute, a single infinitely brief instant would be long enough to see everything, to experience the work in all its depth and fullness, to be forever convinced by it." [A2]

Such infinite acuity in a "brief instant", a thing which reveals itself completely in the view, is an object that imbeds, or more exactly internalizes, the descriptive veracity of the photograph into its construction. Remarkably, Fried not only resolves sculptural "completeness" in visual apprehension, but locates this visuality in an idealized narrative prescription of "experience."

Timme concludes Fried's argument for autonomy, relegating sculptural and site specific intervention to the zone of the photograph, and parodying the condition of post minimal works—for whom materialist reflexivity, socio-political context, and entropic contingency were fore grounded—who are now relegated by history to the singular iconic view of the camera, kept alive in undead form by images. As Roland Barthes explained, "(the photograph) certifies that the corpse is alive, #Kas corpse#K, it is the living image of a dead thing." [A3] or as more apocalyptically put by Siegfried Kracauer, the photograph "annihilates" in its portrayl. Timme exploits the macabre valence of photography, piecing together a melancholic and distinctly pictorial sculptural experience. Expanding the photographic metaphor through the entire show, Timme transforms the gallery itself into a Camera Obscura, literally creating a darkened room, with the skylight above and candle within to cast images on its walls. If we choose to look into the press release, or speak with attendants, we learn the feet, framed in the skylight, belonged to Spike, the vampire protagonist from the television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer, himself the dead who is alive.

One wonders if this is, for Timme, an ironic embrace of the triumph of images over material, or more exactly a strategic foreclosure of the tactics initiated under the mantle of aesthetic materialism. The formal allusions to conceptual art, institutional critique, minimalism, and even California Light and Space, act as a memorial to their imprisonment in the dusty files of conservator backrooms, and art history slide lectures. In their wake, "Luft-air" reproposes sculpture as a distinctly narrative and pictorialist medium, whose efficacy is dependant on the relegation of the viewer to the role of the lone silent observer, reflexive and alienated, set adrift in the gallery's tabula rasa. In this frame, the morphology of material into symbol, history into quixotic narrative, site into non-site, and modernist reflexivity into personal cosmology is complete. "Luft-air" appears most effective as a prolonged lamentation of the possibility for auratic gesture, reproducing the authoritative voice of the artist within a materialist spirituality, and realized in the negative as a makeshift recuperation of a historically revisionist notion of artistic, and personal identity. Either way, the exhibition reflexively alludes to the observation that most contemporary art is resigned to its self-inflicted Lacanian prison, stuck between the actual death of artistic radicality, and the death of its symbolic order, kept alive through a fantasy enabled by black-and-white photographs. Timme places us in this abstracted isolated zone, amongst circuitous associations and intellectual meanders, orchestrating a site outside of the frenetic and temporal. With that ground successfully gained, Timme's exhibition seems all too comfortable in its disassociative symbology. As we follow his constellation of melancholic innuendo, effete sculpture, and poetic provocation, emotional experience—often claimed to have been abandoned by those who innovated many of Timme's tactics—is perhaps less recovered, than it is dictated.

Notes

| [A1] | The source text from "Documents" appeared as follows: "A famous British chemist, Dr. Charles Henry Maye, tried to determine exactly what man is made of and what is man's chemical worth. Here are the results of his scholarly research. The amount fat found in the body of an average human being would be enough to make seven pieces of soap. There is enough iron to make an average nail, enough sugar to sweeten a cup of coffee. The phosphorus would yield 2,200 matches; the magnesium would be enough to take a photograph. There is also some potassium and sulfur, but the amount is too small to be of any use. Those various materials, at the current rate, would be valued at around 25 francs"; "L'Homme," Documents, no. 4, 1929, 215 (Translation: Yve-Alain Bois, 1996). |

| [A2] | Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, Artforum, June 1967. p. 67. |

| [A3] | Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Hill and Wang, New York, 1981, p. 79. |