A Survey on the significance of textiles in contemporary thought and praxis

Anni Albers, "On Weaving", 1965

Anni Albers, "On Weaving", 1965

Textiles have recently been the focus of a number of exhibition and research projects situated firmly within the context of contemporary art and exhibition praxis. They include “Decorum. Carpets and tapestries by artists” (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), “Hollandaise” (Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam), “Social Fabric” (INIVA, London), “The Stuff That Matters. Textiles collected by Seth Siegelaub for the CSROT” (Raven Row, London), “Textiles: Open Letter” (Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach), “Kunst und Textil” (Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg), “To Open Eyes. Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today” (Kunsthalle Bielfeld), “Textile (An Iconology of the Textile in Art and Architecture)” (Zurich University), and “Networks (Textile Arts and Textility in a Transcultural Perspective, 4th to 17th Centuries)” (Humboldt University, Berlin).

Prompted by this situation, we asked art historians, artists, and curators for statements on the question of why textiles have drawn repeated waves of art-world interest since the 1960s, and to what extent their current popularity is due to their affinity with multiple contexts. As well as feminist and queer strategies, this interest focuses on exchanges between fine and applied art (as examined in the historical Arts and Crafts movement or the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s), and between art history and cultural studies with reference to media, social, technological, industrial, and style history. In this context, renewed attention is being paid to the late nineteenth-century writings of Viennese textile curator and art historian Alois Riegl. In these he took textile studies as the basis for establishing a connection between aesthetic formalism and sociological functionalism, examining and demonstrating the interaction of aesthetic, societal, and economic dynamics. This inherent switching between inward and outward references generates shifting perspectives: While the woven structure as pure surface follows a history of style or technology, in its materiality and manufacture it is part of a cultural and social history – an interconnection that also reflects the inseparability of material and immaterial work, between art and craft, as well as highlighting hierarchies in the global distribution of labor and resources.

Increased awareness of textiles’ richly relational mediality, as well as their charged connotations with craft, skill, and knowledge, with the collective and the individual are only some of the aspects explaining their impact. Furthermore, and beyond the technical aspects, there are metaphorical charges that words such as “thread”, “weave”, “knit”, “fabric”, and so forth have adopted through the rhetorics of media studies and social theory. The questions and fields only hinted at here also imply a structural antagonism that not only complicates analysis of concepts of authorship and work, but also continues to raise the question of processes of subjectivization in topical ways.

The following contributions discuss the role of textiles within a curatorial, artistic, and art-historical practice regarding the question of how the confrontation with their multiple contexts can lead to the emergence of criteria for artistic and social criticism.

Translation: Nicholas Grindell

T'AI SMITH

Binding Economies: Tectonics and Sieve

In Gilles Deleuze’s 1990 essay, “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, he mentions textiles in two contexts: First, they are cited briefly as a vestige of the nineteenth-century model of capitalism – an industry that, despite its “complexity”, has been outsourced along with metallurgy and oil extraction to developing countries (textiles exemplify a model of production that economically fabricates reams and reams of plastic- and organic-threaded stuff). Secondly, the textile’s adaptable structure (as a network of flexible threads) is conceived as the underpinning “logic” of the control society: “A sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point” to flexibly control “dividuals” (human subjects) in a society of fob keys, Internet protocols, and passwords. [1]

"Textiles: Open Letter", Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, 2013, installation view

"Textiles: Open Letter", Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, 2013, installation view

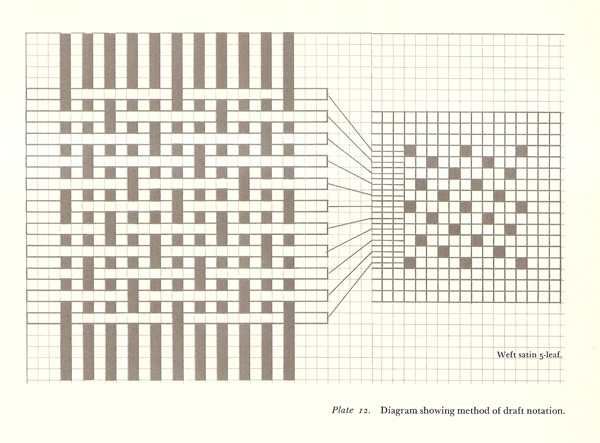

The first type of society corresponds to what Michel Foucault identified as a disciplinary model of production: Machines and humans working in unison, following discrete patterns. One might say that this society, to borrow a term from nineteenth-century architect Gottfried Semper, works through tectonic joints, or a mode of binding discrete thread-like elements. Typically understood through the figure of the grid – a recursive model that carries within its form a sense of order, repetition, and division – the disciplinary society is explicit in the weave draft, a working pattern that diagrams the action of the loom’s heddles. For something particular is at stake in the heddle, a particular advance in the technology that, over several centuries, as Anni Albers wrote in “On Weaving”, “prepared the way for the mechanization of the loom, and contributed to greater speed of execution.” This is so because heddle rods or cords, which are used to space but also raise and lower warp threads in perfectly even and sequenced intervals, function to order the procedure of weaving – to render it uniform. The efficient economy of the heddle is thereby inscribed in the weave draft’s grid. Thus, as developed for patron books and textile manuals (Bindungslehre) – which originated in newly industrialized textile mills in the eighteenth century – the weave draft might be called the quintessentially industrial-modern diagram. Its coded pattern figures the relationship between the abstraction of machinic processes and that of labor under modern capitalism.

The control society is a bit different, Deleuze says; it works like a sieve. In late-capitalist societies with their “flexible” models of work, the textile is reimagined, so to speak, as an operative potential – as that which is adaptable, easily bends. So the figure of the sieve’s mesh is a diagram of the so-called Net (with its complex connections) and of its protocols: The “mesh” here implies a particular manner of distilling data into increasingly malleable threads and then binding or knotting off sections. In effect, in this model of society, the textile migrates from tectonics and stuff (material goods produced on machines, and bought and sold) to an underlying logic of “the fold”; of “infinite work or process” that does not finish, but only ever continues, modulates from corporate boardrooms to social media platforms. [2] It becomes an abstraction of an abstraction.

So, for the purpose of responding to the question, I would say that textile modes are important in art today perhaps because through their plastic forms and methods they generate and conceptualize contradictory modus operandi – the dual methods of global capital. So they imply on the one hand sweatshop labor, and on the other the matrix of the immaterial economy of the Internet, a flexible and adaptive new-capitalist domain; they diagram the economy’s flexible modes of operation, even as they also work within it as material stuff. Effectively, they bind the disciplinary-cum-control societies that currently cross between developed and developing worlds, where one can’t exist without the other.

In this sense, artists who have more recently taken up the problems of textiles (for example, Lisa Oppenheim, Florian Pumhösl, Sascha Reichstein, Yorgos Sapountzis, Zoe Sheehan Saldana, Mika Tajima) do not so much borrow its material specificity or use it as a symbol of this or that idea. Rather, they borrow its contradictory logic; their work enacts its simultaneous objectives of binding, covering, and adapting. The “textile” at play is less an object than that which moves from the domain of plastic form to the temporal folds of concepts, societies, and economies.

Notes

| [1] | Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, in: October, 59, Winter 1992, pp. 3–7. |

| [2] | Gilles Deleuze, The Fold, London 2006, p. 39. It is perhaps important to note that the language Deleuze uses to describe the concept of the Baroque in The Fold maps well onto the language he uses to describe the functioning of the control society. |

Asier Mendizabal

Warp and Weft as Structural Metaphor

1.

The act of alternately interlacing flexible fibers to construct a weave is one of the oldest and most decisive of human abilities. Traces of basket making appear printed on some of the earliest ceramic remains, for which they would have served as molds, suggesting that basketry developed before pottery. It is also thought that rudimentary weaving of flexible fibers preceded, and in fact originated, textile technology. If ceramics are most profusely documented within historical narratives of the earliest technologies – until the successive appearance of bronze and iron – it is due to the abundance of ceramic archaeological remains. For the same reason, stone and metallic remains have given their names to humanity’s pre-writing periods. Due to their ephemeral nature, organic baskets and fabric weavings have not left remains with which to write about cultural evolution or fill museum cases. This, at least, is the pragmatic explanation for why basketry, and textiles in general, which were so crucial to humanity’s socioeconomic history, have been relegated to a secondary place in western historical narratives concerning technologies as carriers of meaning.

It is possible to imagine another reason for this oversight. The account by which gestures and technical skills, whose histories have been inventoried through archaeological remains, acquire symbolic function in the West – that is, how they went from being mere skills to art forms – privileges some of these gestures and not others. Indeed, the following are considered fundamental: Subtraction, in the form of a carving, incising, hollowing out, casting, or grating; addition, in the form of assembling, constructing, or superimposing – the very act of painting; modeling; and the abstract variation of molding or melting down. All of these are physical gestures that originated in the noble actions that made up what history calls the arts. They are modes of giving form to material through direct action upon it. The metaphor of control over that which has no form, over nature. These actions become sign value and are characterized as arts because they account for individual expression, of the force of a subjectivity that leaves a trace of the actions – cutting, hitting, hitching together – a vestige recognizable as the cipher of a subject. Nevertheless, the interweaving of warp and weft, subjected as it is to the grid structure that makes it possible, does not seem favorable for transmitting the individual mark that the historiographical canon has privileged as the motor of progress. To the contrary, it is a skill that seems, within its own structure, to refer to a social act, to collective knowledge.

2.

Before the appearance of photographic technology, the representation of the masses in the illustrated press was achieved via almost abstract filigrees that were consistent with the printing technique used, and that reduced the tiny heads that extended to cover the landscape to an almost textile-like grid of rehearsed marks. Individuals were unrecognizable. The form represented was the totality, and not the sum of its parts. There was a revealing correspondence between this image and the characterization, between suspicious and hostile, that sociology made of the phenomenon as a kind of blind magma, uncontrollable and terrifying, subject to the mechanism of flows more than to the will of its members. Photography, on the other hand, made it possible to capture all the complexity of myriad factions in an instant, in a fraction of a second. In so doing, it generated a paradoxical effect: The form of the mass totality and that of each of the persons that made up the mass could be read simultaneously. An image was thus generated that seemed to resolve the ever-present contradiction in articulating the political – the impossible conciliation between the individual and the collective, strangely resonant with the relationship between the background and the figure in pictorial representation. The perceptive paradox by which, in a weaving, we can only perceive the warp by not seeing the weft or the weft by not seeing the warp.

In 1897 the technique of reproducing photographs directly using a rotary press was introduced. This didn’t allow for good reproductions of photographs of masses of people, however, because the dots that make up the photograph, printed by means of a semitone screen became interwoven with the small heads that formed the image. The grid of dots that made half-tone reproduction possible was superimposed onto the grid of points that formed the multitude of tiny faces in the image represented. The overlapping of the two weaves produced an enigmatic aberration in the related image – a kind of structural metaphor that the graphics industry calls Moiré, borrowing a term from the textile industry.

Translation: Jennifer Josten

Mateusz Kapustka, Anika Reineke, Anne Röhl, Tristan Weddigen

Omissions

Exhibitions are gauges and catalysts of public interest. However, they are only conditionally capable of treating their subject matter in an in-depth academic way. Customary exhibitions focusing on one medium cater to classical notions of art that seek to ennoble textiles. They are staged as artworks, predominantly as paintings or sculptures. This may correspond to the artistic intention, be it reflected or not. But the orientation toward the guiding medium of painting flattens the textile. Its specific spatiotemporal qualities, such as its handling of gravity, its plasticity and tactility, its function as a visualizing foil, the establishment of a context and an-architectural space, the unity of image and carrier, are not brought to bear in displays of this sort. Due to its mode of production and manifestation, the textile prompts one to create superficial analogies and formalistic assimilations that disregard the differences between the variegated object-related and conceptual genres of the textile.

But the textile actually calls the classical concepts of object, work, image, and art into question. This could be a further motivation for art studies to expand its horizon to fundamentally include all objects. In the case of the textile hybrid, the specification of objects necessary to arrive at insights can be achieved foremost by focusing on its transmedial potential. The translation of one medium into another, e.g., from woven fabric into carved stone and vice versa, allows each to be better understood through reciprocal, comparative differentiation. It poses a fruitful challenge to exhibitions and descriptions to bring to light the medial interfaces and incoherences, metamorphoses and misunderstandings.

The two large semantic fields of textile-material phenomena on the one hand and poetic-linguistic metaphors on the other are incongruent. This is indicated, for example, by the inflationary use of the terms textus and fold. After an exploratory phase, the discursive levels of the objects and of concepts must now be connected more precisely at certain points. While analogies are drawn in an increasingly broad way, the gradual separation of object and language probably reflects one of the current problems of art studies. Object-related glossaries can be a help and provide more in-depth knowledge of what exhibition catalogs can only partially deliver.

The hybridity of the textile as a medium, technique, material, and metaphor demands a challenging, inter- and transdisciplinary approach. The alienation between the university and the museum is particularly evident in the area of textile arts. National and international research and training traditions foment methodological mistrust and intradisciplinary xenophobia that seeks security in closed peer groups. What is instead required are conceptual hinges between conservational and academic material research, for instance.

As feminist art studies have shown, the modern master narratives and their guiding concepts of authorship and authenticity have a discriminating impact on research and careers. Although mainstreaming is beginning, the textile and its studies still gets entangled in certain features attributed to them, such as anonymity, femininity, materiality, and craft. Artistic media and their histories, the mingling of media mythology and research discourse, must therefore be subjected to constant disciplinary self-critique. While the canons of epochs, cultures and genders in academic studies are gradually dissolving, the dominant canon of media, which has been expanded but not overcome by contemporary art, still prevents art studies from turning to the object itself.

The textile is close to everyone. As an archaic cultural technique, it suggests anthropological constants that make the medium a playground for false friends. Even if this is excusable in art, everyday experiences, taken to be universal, are not sufficiently specified in science with a view to social and cultural history. Due to their mobility and multifunctionality, their global production and distribution, textiles are today not only in the focus of public and artistic interest but also the subject of transcultural research as a medium of exchange. However, the project of “interweaving the globe” should not stop at the migration of forms, understood as a history of styles and in a politically neutralizing manner, but it must consider the direction in which resources flow as well as the increasing inequalities in the exchange system. Even if the textile has tended to test-run alternative, non-capitalistic conditions of production since the industrial revolution – from Arts and Crafts to Guerrilla Knitting – these are often rehashes of old, neo-primitive, art-historical material myths and therefore political kitsch and symbolic substitute actions. Even the roles of victim and perpetrator and the distributions of power defined in terms of gender in the field of the textile have been far more complex ever since Arachne than conventional gendering in the medium presumes. The textile is fundamentally political, it is the fabric of social conflicts, as the history of the weaver uprisings has shown. In the case of the textile, there is always the danger of the ornament covering up the material, of formalism concealing politics.

All these expectations and omissions tear at the textile in different directions. But instead of leveling it, the issue is to fight for the textile, to turn it around and inside out, to stitch it together. The textile is not an archaic hut displayed at world fairs, a worldwide tent, a protective sheath, but a tense zone of contact and conflict.

Translation: Karl Hoffmann

Judith Raum

Judith Raum, "Disponible Teile", Galerie Chert, Berlin, 2012

Judith Raum, "Disponible Teile", Galerie Chert, Berlin, 2012

Several interesting aspects come together in the textile medium. First, its phenomenological constitution: As Michel Serres describes it, [3] the textile is a medium that, as opposed to harder ones, represents something softer and more fluid. The textile is more prone to decay than other materials – it tears and wears more easily and ultimately disintegrates. That makes it similar to the corporeal, not least due to its flexibility and the attendant ability to adapt to grounds and forms, to dress them and become a second skin, so to speak.

Grasped in this way, what interests me in current works is where the textile appears within economic and colonial projects – within endeavors that have established “hard” structures. Not only in the sense of infrastructures, buildings and industrial plants, as in the case of the construction of the Baghdad Railway in the Ottoman Empire, which was (indirectly) operated by Deutsche Bank, but also in the sense of the mindset with which the economic penetration of a country was pursued.

In these contexts, I understand the textile as a resistive medium, because on the phenomenological level it appears to undermine the “hard” structures that are to be established. Within German economic colonialism and technology export at the end of the 19th century, for example, I am interested in the moments when such transient things as cotton and wool threads become significant. When tarpaulins, shawls and cloths play a role, when utensils and materials that have more to do with temporary forms of life than with stable structures are put to use. When, to speak on a different level, hierarchies deemed valid enter into a state of flux, when both the forms of production and the usage of certain materials allow process-related changes more than they reinforce prevailing conditions.

The phenomenological dimension of the textile connects with its socio-historical and economic-historical dimensions: cloth, fabric and clothing satisfy fundamental human needs; the knowledge of weaving, felting and knotting is age-old. But it is precisely the weavers and workers in the textile industry that have long been working under the most precarious and incapacitating conditions, while the accumulation of capital is also based on the production of textiles. The continuity of the close ties between large banks and the business with the textile medium is curious. Deutsche Bank’s chairmen of the board were members of the founding committee of the Deutsch-Levantinische Baumwoll-Gesellschaft operating at the end of the 19th century, for example, and repeatedly and actively encouraged the aggressive approach of the German cotton industry in Anatolia. Already in 14th-century Tuscany, there were close connections between the banking and textile sectors; the “hard” and “soft” currencies were often owned by one and the same powerful institution. In 1374, the wool beaters and weavers put their finger on the then prevailing grievances and criticized in a surprisingly topical way the financial, tax and wage policies of the times.

In my paintings and objects, textures and methods become readable that refer to the phenomena described above. The lengths of cotton fabric treated in layers and precariously assembled objects are spanned with ropes or installed in the space supported by bars. They become components of a flexible architecture in which they form a context together with documents of my socio- and economic-historical research. For me, the textile is not least the medium I have an affinity to as a painter, in a sense also described by Michel Serres: The textile is the skin of the painter, into which experiences are tattooed. The textile carrier possesses a topological dimension in that it is a place where touching is not subordinated to seeing. At issue here is how I touch a surface, how the paint penetrates the fiber. For the eye, this results in the extent to which certain layers relate to each other in a planned or coincidental way, whether connections appear loose or solid, whether something remains open or has already been determined. Hence, for me, the textile always raises questions as to the manner of painting, questions that simultaneously refer to the basic problems of representation.

Translation: Karl Hoffmann

Note

| [3] | Cf. Michel Serres, The Five Senses, London/New York: Continuum, 2008. |

Leonor Antunes

“In an anagram all the elements exist in a simultaneous relationship. Consequently, within it, nothing is first and nothing is last; nothing is future and nothing is past; nothing is old and nothing is new …. Each element of an anagram is so related to the whole that no one of them may be changed without affecting its series and so affecting the whole. And conversely the whole is so related to every part that whether one reads horizontally, vertically, diagonally or even in reverse, the logic of the whole is not disrupted, but remains intact.”

—Maya Deren

In Maya Deren’s film “The Witch’s Cradle”, we watch a series of choreographed movements performed by Marcel Duchamp and the camera. Part of the film’s sequences are interrupted by -Duchamp manipulating a piece of yarn that suddenly starts making its own journey around his body. The thread moves from the controlled manipulation of the human hands to the liberation of the “magical” qualities set by the camera. Deren was comparing the Surrealist objects to magic and cabalistic symbols, like when she parallels string games played by a little girl (evoking the mythological figure of Ariane’s thread) with a second string that goes first along the leg of a man then circles around his neck, luring us into the movement of the flying bowline.

In one of the (unfinished) film’s final sequences, we see a body moving backward, pulling the thread attached to the camera. The physical limit of such movement is controlled by the thread’s tension. The thread has a metaphorical meaning, due to the context of Deren’s work and the film’s location. It was shot in New York in the former space of Peggy Guggenheim’s collection “Art of this Century” designed by Frederick Kiesler in 1942. Kiesler conceived a labyrinthine and Surrealist space that was both mobile and demountable; a conceptual space that explored all manners of aperture, curtains, hanging walls, and rope systems.

Maya Deren, "The Witch's Cradle", 1943, film still

Maya Deren, "The Witch's Cradle", 1943, film still

I am particularly interested in the relationship established between the line, or yarn, with the body, as a unit of measurement, which is defined in relation to the scale of the human body and the spatial environment around it. The idea of a string tied around the fingers serves as a mnemonic device. I am also interested in the relationship of the body with built space using an element that develops within it being manipulated and deployed. This device can be seen as a rope, which through its successive knots and displacement defines surfaces which in turn define volume.

In 2011 I did a commissioned project for the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid. The project titled “walk around here walk through there”, was quoting Maya Deren’s instructions to Anne “Pajarito” Clark (the artist and mother of Gordon Matta-Clark) who was performing in the film, indicating to her how to move in the space. In this exhibition a black nylon rope was placed on the ceiling creating a hexagonal shape, forming a net from which several black leather sculptures were suspended. The sculptures’ weight concealed the rigid hexagonal pattern created on the ceiling. The rope’s leftovers were kept on the floor, as a line going from the first room to the second and returning back to the first room and thus leading the spectators to a “possible” way out. I always use an entire spool, and try to move the rope in the space without cutting it. I see it as a way to reactivate the use of line moving in space.

Recently I have been looking at the ways certain indigenous tribes in Brazil are weaving different materials, how they manipulate and -produce volume within different densities and purposes. The Xingu tribes, in Mato Grosso, which I am visiting this year, still use their traditional techniques and work with natural fibers that they cultivate in their region. It is interesting how such looped fibers and handcrafted mats can literally expand infinitely in space, in all directions, building a structure with no apparent limits or end. Or the way they fabricate nets for hammocks using very basic looms, bringing to mind how nets have no end, like a Möbius strip, having the same mathematical quality of being nondirectional.

I am interested in the dialogue that this specific knowledge establishes within a certain perspective of modernity in Brazil. How architects like Lina Bo Bardi engaged with the vernacular, with Afro-Brazilian culture and native expressions of the Brazilian northeast; which serves as a dramatic counterpoint to the recent notion of the “Presence of the Past”.

Bo Bardi’s passion for new engineering solutions and for the handicrafts of the complex ethnic and racial demographics of Brazil’s regions were not the nostalgia for a world before modernism, but rather a legacy regarding a belief in the artwork as representing an ongoing engagement in a process, rather than a singular assertion of an object as a utopian frozen moment.

Within the multiple ways of reading fabrics, what I find most striking are exhibitions that can activate space the way in which fabrics do, the way that weaving builds a structure row by row, layering or piling specific knowledge on top of each other; crafting a platform for social political and economic interaction of a world of real possibilities.

Koyo Kouoh

HOLLANDAISE. A journey into an iconic fabric

The bright and distinctive wax prints that I worked with in my exhibition “Hollandaise – a journey into an iconic fabric” at Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA) and Raw Material Company in Dakar are generally regarded as African fabrics, while there is nothing African about them, be it in their production technique, their design, their manufacture or their commercial marketing. The history of wax prints is an emblematic tale of commercial domination that began in the middle of the nineteenth century and continues down to today. It is also a tale of the – to put it mildly – transfer of the skills of the Indonesian batik tradition to Dutch textile manufacturing. The specific wax technique is used today by the Dutch company Vlisco, and many others, was traditionally developed in Java, Indonesia, and brought to the shores of Africa in a grand project of commercial expansion.

I would argue that the emergence of a modern consciousness during the pre- and post-independence era accentuated an African orientation toward Western-style clothing that was already there from the early years of colonization. One must know that modernity in an African perspective does not necessarily relate either to the period or to the set of ideas associated with that term in Western societies and rather relates to a period of self-assertion, a leap in education, self-reliance and economic prosperity that followed the liberation movements in the mid-twentieth century.

It was also during this period that wax prints were increasingly embedded in the traditional order – at least in Cameroon – as a means of drawing the line that divided tradition and modernity. The ultimate result of this was the social interpretation of the use of wax prints, which identified someone wearing wax prints as traditional, and someone in Western clothing as modern.

In the process of digesting colonialism and its various aftereffects that are still being experienced today on political, psychological, cultural and economic levels, blaming Europe is a welcome, recurrent pattern. While the French and the Brits get more than their share, one rarely hears the Dutch mentioned. I was intrigued by this, especially when you look at how an iconic Dutch product has become the defining metaphor for African design, fashion, and expression that symbolizes identitarian “authenticity” within Africa, and in the eyes of those looking at it: wax prints (also commonly called Hollandaise, in their high-end version). The wax print is both a fake, and nevertheless a true sign of Africanness worldwide.

Regardless of its origin and the exploitative mechanisms attached to it, this fabric has been adopted, and through its use has created a local meaning of its own and a hierarchy of styles and quality that should not, and can not, be denied. Ever since wax prints were introduced in Africa, women have collected them, along with other textiles such as batiks, lace, and Congolese damas. These collections are part of what can be seen as a sort of underground feminist project that serves to provide financial independence to women outside their husband’s knowledge and control. They are a form of savings. Beyond the financial value of the fabric, the vintage pieces also give the wearer prestige and an aesthetic edge.

It was estimated that 75 percent of all wax prints in Africa displayed Vlisco designs, according to postings on Vlisco’s website, but only a portion of these were theirs. Around 2006 the cheaper imitations from China seriously threatened the continuation of the firm. To combat this trend, Vlisco decided to become a leading fashion brand in Africa. Since that date Vlisco advertises with the subtitle “The True Original”. The company now not only produces new designs for wax prints, but also launches these as collections with the rhythm of the fashion trade. An advertising campaign accompanies each collection, and flagship stores have been opened in major cities of West Africa. The photo shoots for the quarterly advertising campaigns are organized by a Dutch agency in Amsterdam. Black models are hired to perform Africa and the ultimate look of the stylish African woman. With this strategy, Vlisco perpetuates the biased idea of African authenticity by suggesting that the authentic African woman is dressed in wax prints, and preferably “true original” ones.

It is worth mentioning at this point that over the past two years of preparation for this exhibition, during which SMBA and I repeatedly sought Vlisco’s support for the artists’ research, the company displayed a resolute rejection of the exhibition project. The level of criticality which we were bringing to the debate around wax prints did not appeal to their purely commercial interest and growing anxiety about remaining a market leader. The company did not understand that this exhibition is not meant to put them in the spotlight, but rather to offer a new reading of the idea of African identity that wax prints convey in general. It is intriguing that after more than a century of dealing with an iconic product, the company has not managed to draw from the wealth of creativity of design professionals in Africa and its diaspora. Save for popular culture imagery, the predominant visual lexicon of Vlisco’s wax prints still draws its inspiration from African fauna and flora.

This statement is an excerpt from my article in the exhibition catalogue “Hollandaise”, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam and Raw Material Company, Dakar, 2012/2013.

Irene Below

The aim of the show “To Open Eyes. Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today” at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld, the “city of linen”, was to investigate the connection between social history and the development of textile art. For the museum director and curator Friedrich Meschede, the exhibition thematized the development from the applied textile art of the Viennese Workshops to autonomous “pictures made of fabric”. A midpoint along this path was occupied by the Bauhaus weavers, above all the Bauhaus member Benita Koch-Otte, who from 1934 onward was active for close to thirty years as the artistic director of the weaving mill at the Bodelschwinghschen Anstalten Bethel near Bielefeld. The broad range of her works until 1933 could be discovered in 2012 in exhibitions in Weimar and Berlin; Kunsthalle Bielefeld now showed later works as well. My catalog text on Koch-Otte’s life and work [4] dealt with, among other things, her activities in Bethel under the conditions of National Socialism, her therapeutically founded concept for the weaving mill, and the pressure to adapt as a Bauhaus graduate and foreigner returning from exile. I derived information concerning the latter point predominantly from Koch-Otte’s letters to her close friend Gunta Stölzl in Switzerland, in which she described her rejection of the political conditions in Germany, her difficulties with the Christian milieu and her ambivalences regarding the structures in Bethel and the weaving mill. I placed the political concessions that Koch-Otte had to make in this context – the master craftsman’s exam in 1937, since the Bauhaus degree was not recognized, and the production of two, now lost carpets with Nazi emblems for municipal facilities, one of which survives in a photograph. These concessions allowed her to be repatriated and to conceive the handicraft enterprise in Bethel as a therapeutic-artistic place for disabled, sick and healthy people. It contributed to saving the lives of patients in Bethel who were threatened by euthanasia measures. To this end, the weaving mill made use of the positive stance toward craft and domestic textiles rooted in the Nazi ideology. The reference to the long tradition of domestic textile craft, especially weaving, served to legitimize the work at the weaving mill. For example, at a procession of the Anstalten on May 1, 1941, there was a historical, rural weaving mill on the wagon of the weaving school; on a second one, with the inscription “Spinning and Weaving are Our Duty”, a linen weaver, spinning girls and female peasants in historical garbs. In this frame, Koch-Otte was able to stylistically and thematically continue her work which she had begun as the director of the weaving mill at Burg Giebichenstein in Halle until she was discharged in 1933. This is shown in the loose-leaf collection “Deutsche Warenkunde”, a self-presentation of the Betheler workshop from around 1940. One sheet depicts the star carpet designed in Halle in 1932, which was still woven in Bethel, the second shows a wall fabric designed in 1940 – photographically presented similar to the wall fabrics of Burg Giebichenstein ten years earlier. However, the experimental combination of materials is now replaced by a more conventional fabric of flax and wool.

"To Open Eyes. Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today", Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 2013-2014, installation view

"To Open Eyes. Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today", Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 2013-2014, installation view

Until today, the relationship between Bauhaus modernism and National Socialism is a rather blind spot in Bauhaus research. The at first open, then for a long time ambivalent stance toward National Socialist design tasks and commissioners in the cases of Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and others is usually disregarded and suppressed, as are the corresponding designs and completed works. Only in recent times has the attempt been made to precisely examine the complicated living and working conditions in these years and the behavior oscillating from case to case between currying favor and resistance. It would be informative to do so also under the aspect of different materials, media and genres and consider the fact that modern designs were accepted more in arts and crafts and apparently also in textile art.

My catalog contribution written in this vein, along with the picture of a carpet with National Socialist emblems, led to the critical question in the daily Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung: “What to think of an artist who in her work brought together NS symbols and the Bauhaus which was shut down by the Nazis?” [5] In her review in the weekly Welt am Sonntag, the critic Christiane Hoffmann then attacked the entire exhibition and the director of the museum, ending with the words: “How can Friedrich Meschede grant space to the artist Koch-Otte without mentioning that she earned money with woven Nazi symbols? In this respect, the director discredits his exhibition and himself.” [6]

I never received an answer to my letter to the editor in which I outlined Koch-Otte’s adverse stance toward National Socialism, the biographical circumstances and her art-therapeutic concept. When I inquired, I was told that an abridged version was to appear, but it was neither printed nor placed on their Website.

“To Open Eyes. Art and Textiles from the Bauhaus to Today”, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, November 17, 2013 - March 2, 2014.

Translation: Karl Hoffmann

Notes

| [4] | Irene Below, “Man baut jetzt in Bielefeld ein Kunsthaus, u. es sind wohl auch manche gute Dinge im Depot‘. Benita Koch-Otte – Eine Hommage”, in: Friedrich Meschede/Jutta Hülsewig-Johnen with Christina Lehnert/Henrike Mund (eds.), To Open Eyes. Kunst und Textil vom Bauhaus bis heute, exh. cat., Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2013, p. 88–99. |

| [5] | Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung, 11/25/2013, http://www.noz.de/deutschland-welt/kultur/artikel/428574/kunsthalle-bielefeld-zeigt-textilkunst. |

| [6] | Welt am Sonntag, 12/1/2013, http://www.welt.de/print/wams/nrw/article122431469/Unter-dem-Teppich.html. In a commentary in the same issue, http://www.welt.de/print/wams/nrw/article122431470/Bielefeld-und-die-Vergangenheit.html, the entire affair is scandalized against the foil of the history of the Kunsthalle’s name: It was endowed by Rudolf August Oetker in 1968, and despite recurring vehement protests until 1998, named after Oetker’s stepfather Richard Kaselowsky, a member of the “Freundeskreis Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler”, a party member and director of the company during the time of National Socialism. The publication of the study “Dr. Oetker und der Nationalsozialismus” after the death of the company patriarch, in which the long disputed, close ties of the firm and the family to the National Socialist regime were proven once and for all, appeared a few days before the textile exhibition was opened. |