Lost Traces of Life A conversation about indexicality in analog and digital photography between Isabelle Graw and Benjamin Buchloh

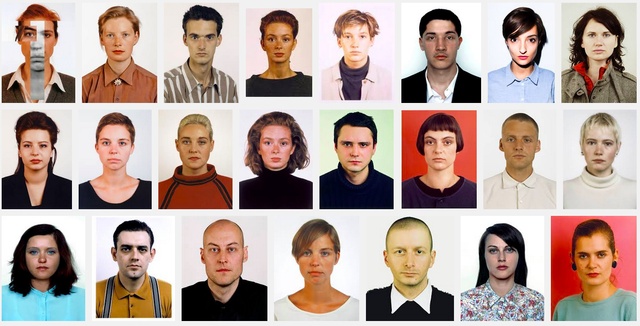

Google image search for "Thomas Ruff Portraits“

Google image search for "Thomas Ruff Portraits“

There is no theory of photography without the question of indexicality: the influential studies of Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, and Rosalind Krauss persist in contemporary photo discourse and beyond. And though virtually no one still believes in the photo-image’s claim to truth, the promise of authenticity, however illusory, continues to compel us.

But how can we characterize the relationship between the image and its referent today? Looking back, has our perspective on the history of photography, on the iconic works of the Bechers or Maholy-Nagy’s New Vision, changed? As images proliferate, the imaging (and editing) of the self in particular, what new questions are raised? In the following pages, Isabelle Graw and Benjamin Buchloh discuss not only the semiological interpretation of the photographic image, but also the photo-image’s potential as a form via which subjectivity constitutes itself.

Benjamin Buchloh and Isabelle Graw

Benjamin Buchloh and Isabelle Graw

Benjamin Buchloh: If I understand you correctly, I think that you’ve offered a slightly reductive version of the semiological definition of photography. Photography’s mystery or allure, at least until the advent of digital production, was always that its mode of representation could be both indexical and highly iconic at the same time. In other words, Peirce’s two basic concepts operated in tandem in the photograph. It’s worth keeping in mind that, in the mid-nineteenth century and again in the 1920s (which is to say, during photography’s golden period), this duality of the photographic image was of central importance to its theory and practice: Anna Atkins and Fox Talbot, for example, were fascinated by both the medium’s purely indexical dimensions and its iconic capacity. Fox Talbot stressed both aspects as equally important in constituting the photographic image. This duality then re-emerges, though as part of a wider-ranging discussion, in the 1920s; see, for example, the debate between Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision and the New Objectivity of Albert Renger-Patzsch. Moholy claimed that the realism of light’s indexical trace offered a new unmediated materiality, championing a novel technological conception of realism, unfiltered by subjectivity, that went far beyond traditional notions of representation. By contrast, the New Objectivity – as we already know from Benjamin’s “Little History of Photography” – demonstrated a return to a much more conservative conception of realism. Here, photography was considered predominantly in terms of its iconic dimension, which is to say the narrative structure of pictures. There was no interest in activating the beholder through indexical confrontation; rather, an earlier depictive style was privileged, a narrative realism that promoted a purely iconographic conception of the photographic image. A third history of photography lets us retrace this shift toward conventionalism, one that takes into account Düsseldorf between 1960 and 1980 and Bernd and Hilla Bechers’ influence there at the time. In the Bechers’ systematic approach – in their radically strict self-limitation to very specific, defined historic architectonic structures – one finds that the indexical quality of photography, here mapping a correlate of these structures, still played a central part. It is only in the works of the Bechers’ students that the narrative and traditional register of iconicity is fully brought back into action (for example, in the revival of genres like the “portrait” or the “landscape”).

Graw: Certainly photography has always been more than just a matter of indexicality – hence my earlier mention of “index effects.” And I would argue that “portrait” and “landscape” are present even in the Bechers’ own photographic series, which is to say prior to being more fully expressed by the generation they taught. It would seem that certain iconic tendencies were already implicit in the Bechers’ work, with their students then carrying these tendencies to extremes. True, the Bechers’ photographic project was a kind of industrial archaeology, appearing only all the more so given the serial and systematic aspect of their output: capturing highly specific types of industrial facilities, set in unspectacular landscapes, always deserted, usually before a neutralizing gray sky. Such an aesthetic, one wherein the artist subject aims to efface all traces of his/her own involvement, underscores the photograph’s role as a record, as pure registration. On closer inspection, however, things turn out to be more complicated with the Bechers’ images: the industrial facilities – I’m thinking, here, of their “Pithead Frames” and “Water Towers” series – emerge as lead actors. There is seemingly nothing mediating our view of them. As these objects come into their own in an aesthetic sense, we can also study their physiognomy, which is comparable to, say, the bodies in August Sander’s portraits. This personifying view is borne out by the Bechers’ own choice of words: their stated aim was to penetrate the “essence” of their objects, to “familiarize themselves” with selected buildings and then see how they compare. [4] These are terms we ordinarily use when speaking of people; effectively, the Bechers’ project was thus a kind of portraiture. Later on, this aspect of portraiture – whose purpose, as in Sander, is classification and typologization – is isolated and blown up; for example in Thomas Ruff’s work, which combines monumental proportions with the anti-expression of New Wave aesthetics. So where you see discontinuities, I see the unfolding of something that was in fact already latent. In the end, the portrait genre, together with this sense of an authorial artistic subject making certain defining choices, reappears in the Bechers’ work through the back door, wouldn’t you agree?

Bernd and Hilla Becher, “Water Towers,” 1965–82

Bernd and Hilla Becher, “Water Towers,” 1965–82

Buchloh: I think you’re making a very interesting argument but I still take a different view. I would say it was exactly the Bechers’ radical self-limitation to highly specific architectures and deserted spaces that gave rise to this extreme dialectic, a dialectic in which the ambitions both of New Objectivity and of documentary photography were put into historical perspective or even overturned altogether. In other words, their radical concept was based on the insight that neither Sander’s nor Renger-Patzsch’s models nor Moholy’s New Vision had any purchase left in postwar Germany or elsewhere in Europe. It was the rigidity with which the Bechers insisted on this double negation that made for an immensely complex epistemological difference between their work and earlier photographic practices in Germany. In that regard, one might actually compare their output to that of Ed Ruscha: in the books he started making in 1962, he similarly finished off the notion that certain photographic conventions or subjects could be of timeless relevance. By comparison, the work of the Bechers’ students does represent a distinctive slide into conventionality; they turned, quite simply, into very good photographers, and in retrospect their artistic potential looks less radical.

Graw: Because of photography’s automatic quality, art scholars usually regard it as an art form that undermines authorship. Most recently, Robin Kelsey used Adam Smith’s metaphor of the invisible hand to characterize the medium’s agency and, more importantly, what he calls its “chance nature.” [5] Indexicality similarly suggests an automatic and physical self-inscription of the object that does not necessarily require the presence of an author; it indicates a vacancy of the position of subjectivity or intentionality. Some critics have accordingly understood the index as an anti-subjective procedure that records the ghostly traces of vanished objects; not least, for instance, Rosalind Krauss’s “Notes on the Index.” [6] Would you stand by this reading of the index as a critique of authorship today?

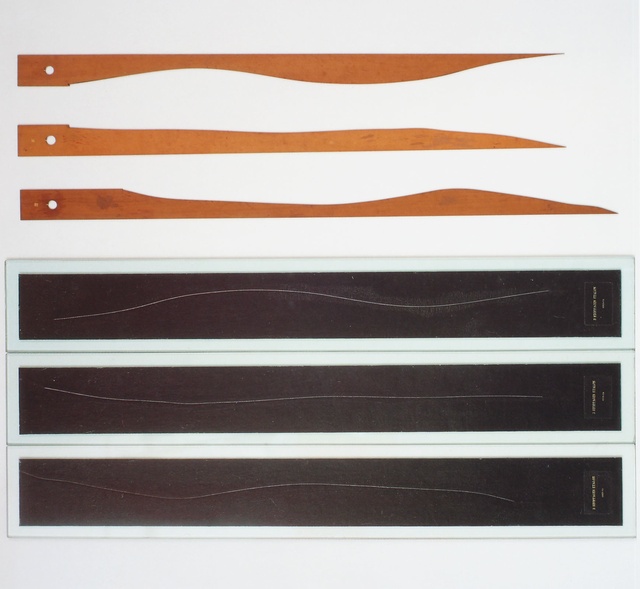

Marcel Duchamp, "3 stoppages étalon" (3 Standard Stoppages,

detail), 1913/14

Marcel Duchamp, "3 stoppages étalon" (3 Standard Stoppages,

detail), 1913/14

Richard Serra, "Splash Piece: Casting,“ Jasper John’s Studio,

New York, 1969/70, installation view

Richard Serra, "Splash Piece: Casting,“ Jasper John’s Studio,

New York, 1969/70, installation view

Buchloh: No, that is not a reading that I would defend today, although we would need to examine the reasons for the disappearance of indexical radicalism as an anti-subjective operation in greater detail. The historic key moments of performative indexicality, from Marcel Duchamp’s “3 Standard Stoppages” in 1913 to Robert Rauschenberg’s “Tire Print” (executed in collaboration with John Cage in 1953) and Richard Serra’s first “Splash Piece” in 1968, did pursue an important agenda that we shouldn’t discount – even if, from today’s vantage, these projects may seem utterly obsolete. By eliminating subjectivity from the gestures of painterly and sculptural production, they not only proposed an anti-authorial and profoundly participatory anti-aesthetic; in all three cases, it was also the (post-)Surrealist hope of achieving a liberation through and by means of freeing the unconscious (as championed by André Breton) and locating it beyond the registers of the technological regimes of control, which was exposed as a false promise. However, in a contemporary world – wherein we experience an ostensible reduction of indexicality to pure presence or pure production, which has now long been part of the standard arsenal of the culture of spectacle – these are no longer the questions or challenges we face.

Graw: Should we really associate the works of these artists with an anti-authorial aesthetic, given that they are the ones who initiated and triggered the experimental artistic setups in question? In one of the pieces you’ve mentioned, Rauschenberg’s “Tire Print,” the artist directed the project throughout: he glued the sheets of paper together, provided the black paint, and asked his friend John Cage to come by in his Ford Model A and drive over the paper he laid out in the street. The resulting tire track motif is not just the outcome of a specific experiment the artist arranged; it also bears the mark of John Cage, a renowned and influential artist of the time, or more precisely, of the style of his driving and car. Might we not say that the work’s implicit critique of authorship is counterbalanced by John Cage’s ghostly presence in it?

Buchloh: It’s wonderful to hash out the illuminating differences between our views of these works. Still, we do need to take into account the circumstances that were necessary for “Tire Print” to be realized – which is to say the conventions of post-automatic painting that prevailed at the time – in order to situate the specific qualities of Rauschenberg/Cage’s intervention. In other words, we need to understand this intervention as an explicit opposition to the mythology and heroic ambitions of Pollock or Barnett Newman in which the art world was invested. Similarly, it would be a mistake to read Duchamp’s “3 Standard Stoppages” with its deliberately complicated (and deeply ironic) acts of preparation, execution, and exhibition as a renewed affirmation of authorship and production, when they were, before anything else, a brilliant deconstructive comment on the pretensions of Cubism.

Albert Renger-Patzsch, "Aluminiumtöpfe, Warenhaus Schocken, Zwickau," 1926

Albert Renger-Patzsch, "Aluminiumtöpfe, Warenhaus Schocken, Zwickau," 1926

Graw: I didn’t read “Tire Print” as an affirmation of authorship – my contention was rather that an altered version of the principle of authorship indirectly resurfaces in this piece, in the traces of paint left behind by the car with John Cage at the wheel. I do concur with your other point: that to arrive at an adequate understanding of what is at stake in a work of art, we need to situate it in its historic context. But we now live in a digital world. Would you agree with the observation that there no longer are any indices in today’s world because their existence requires analog recording technologies? Or might we characterize the data traces generated by digital imaging as indices as well?

Buchloh: I’m probably the wrong person to be asked this question! I really haven’t at all studied how the rise of digital technology has influenced the theory and practice of photography so I should therefore be cautious about even attempting an answer. But there’s one thing that does seem certain: digital technology has utterly changed and perhaps even undone the material basis that analog photography had presupposed. To stick to the examples from the Düsseldorf School, what makes Andreas Gursky’s work so repugnantly appealing and explains the enormous success he’s had is primarily his strategy to fuse the indexical, iconic, and post-analog photographic semiologies of the photographic image – or rather, to make them cancel each other out. As a result, his pictures present us with a world devoid of critique or analytical contradictions, a stage on which the regime of the spectacle is naively celebrated as irresistible and insurmountable. This is in fact not unlike Renger-Patzsch’s New Objectivity, where a naive fetishistic faith in machines and technology underlies the idealization of the world as it was.

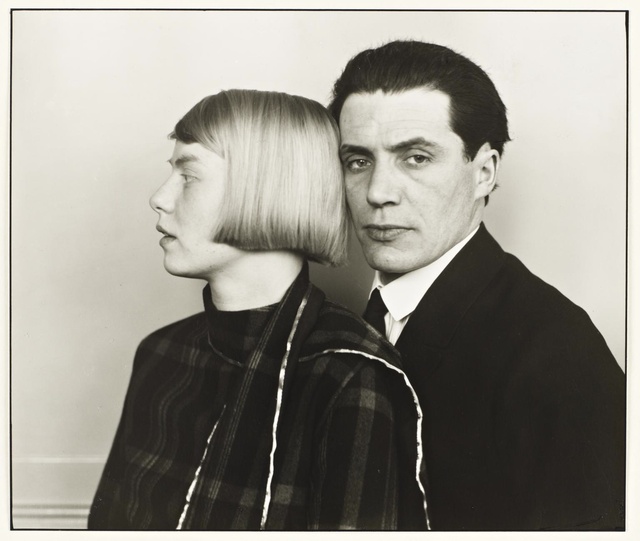

August Sander, "Architektenpaar. Der Architekt Hans Heinz Lüttgen und seine Frau," 1927/28

August Sander, "Architektenpaar. Der Architekt Hans Heinz Lüttgen und seine Frau," 1927/28

Graw: It’s certainly the case that Gursky’s pictures present a world without critique. I’m just not sure we can find fault in his work for suspending the tension between the indexical, iconic, and post-analog registers given that it demonstrates that these types of signs can, in fact, peacefully coexist. What’s more, everyone today already assumes the constructed nature of the digital image; calling its authentic relation to life and reality into question has become routine. And yet with some pictures – selfies, for example – “authenticity effects” cannot help but be transmitted. However much a selfie may have been manipulated and edited, its core purpose is to authenticate presence, along the lines of: I was here; I still exist. Selfies, I would argue, feed on photography’s indexical potential, especially since the subject who triggered the shot appears before the camera. When people edit and enhance these pictures, perhaps they’re trying to breathe life into them, to animate them, at the very moment when their hold on some indexical keepsake of that life has become less certain?

Buchloh: The question of whether the selfie retains a vestige of the index is hard to answer, although technically speaking, the picture’s indexicality remains in place. But indexicality also always presupposed a subject conscious of the material realities of the production of photographs; that subject, as Walter Benjamin noted with a view to the portrait of young Soviet pioneers, may not yet have had any uses for an image of its own likeness, but there was, at least, a confrontation of a possible future self with the technological possibilities of contemporary photographic production. Today, we seem to have largely lost this horizon of a possible new future self, and so I would say that the material indexicality of the digital image is insignificant as well – it was already manifestly insignificant when the Surrealists and, later on, Andy Warhol repeatedly posed for the Photomat. These artists were keenly aware that the days were numbered for the kind of subject that lent itself to indexical and iconic reproduction – the obliteration of subjectivity worked hand in glove with the power of the novel technologies of self-delusion.

Kanye West and Kim Kardashian, via Instagram, 2015.

Kanye West and Kim Kardashian, via Instagram, 2015.

Graw: Why is it that you say that the subject has been “obliterated” in media society? In the 1960s, in particular, the point was to redefine what subjectivity was under the conditions of the contemporary media environment, to envisage it as an alienated, split, mediated, non-authentic consumerist subject: see, for example, Warhol’s fascination with seemingly every last detail about this subject and the reality of its life. The members of his Factory in many ways labored under the requirements of celebrity culture, but within that culture they also fought for, and won, new possibilities for action, self-conception, and sexual identity. Concerning the selfie, I would similarly argue that, in allowing for general cosmetic and more radical alterations to our looks, it departs even further from the idea of the authentic bourgeois subject than the photo booth picture. Still, the subject that perpetually reinvents and remakes itself in the selfie remains sovereign to a certain degree. It asserts itself in the picture, reminding others of its existence, signaling that it is alive and trying to retain some control of its life, struggling against the ultimately inescapable pressures of a new economy even as it effectively caters to them.

Buchloh: The question of the demise of subjectivity has come to feel a little worn out today – now that few still believe that emancipation will come through the disintegration of bourgeois conventions of subjectivity. My instinct here, as always, is to return to the prognoses of the Frankfurt School. They foretold in detail the processes of the breakdown we’re currently feeling: the only subject that’s presented to us in the public arena now is a spectacularized substitute for subjectivity; all forms of traditional subject formation look utterly obsolete and ridiculous in comparison. The contemporary art world perfectly illustrates this development – take, for instance, the symbiosis between Kanye West, Steve McQueen, and the Kardashians recently displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In this, we see the new subject of our contemporary world, at least in the realm of cultural practice.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Notes

| [1] | Charles S. Peirce, “What Is a Sign?” in: The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings, Vol. 2: 1893–1913, Bloomington 1998, p. 9. |

| [2] | Ibid., p. 6. |

| [3] | A term I owe to Diedrich Diederichsen, who used it in his inaugural Adorno lecture in Frankfurt/M. on June 16, 2015. |

| [4] | See Bernd and Hilla Becher, Die Architektur der Förder- und Wassertürme, Munich 1971, pp. 11–18. |

| [5] | See Robin Kelsey, Photography and the Art of Chance, Cambridge, Mass. 2015, pp. 311–12. |

| [6] | See Rosalind Krauss, “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America,” in: October, 3, 1977, pp. 68–77. |