ANTI-PASTORAL Dan Ward on Carol Rhodes at Alison Jacques Gallery, London

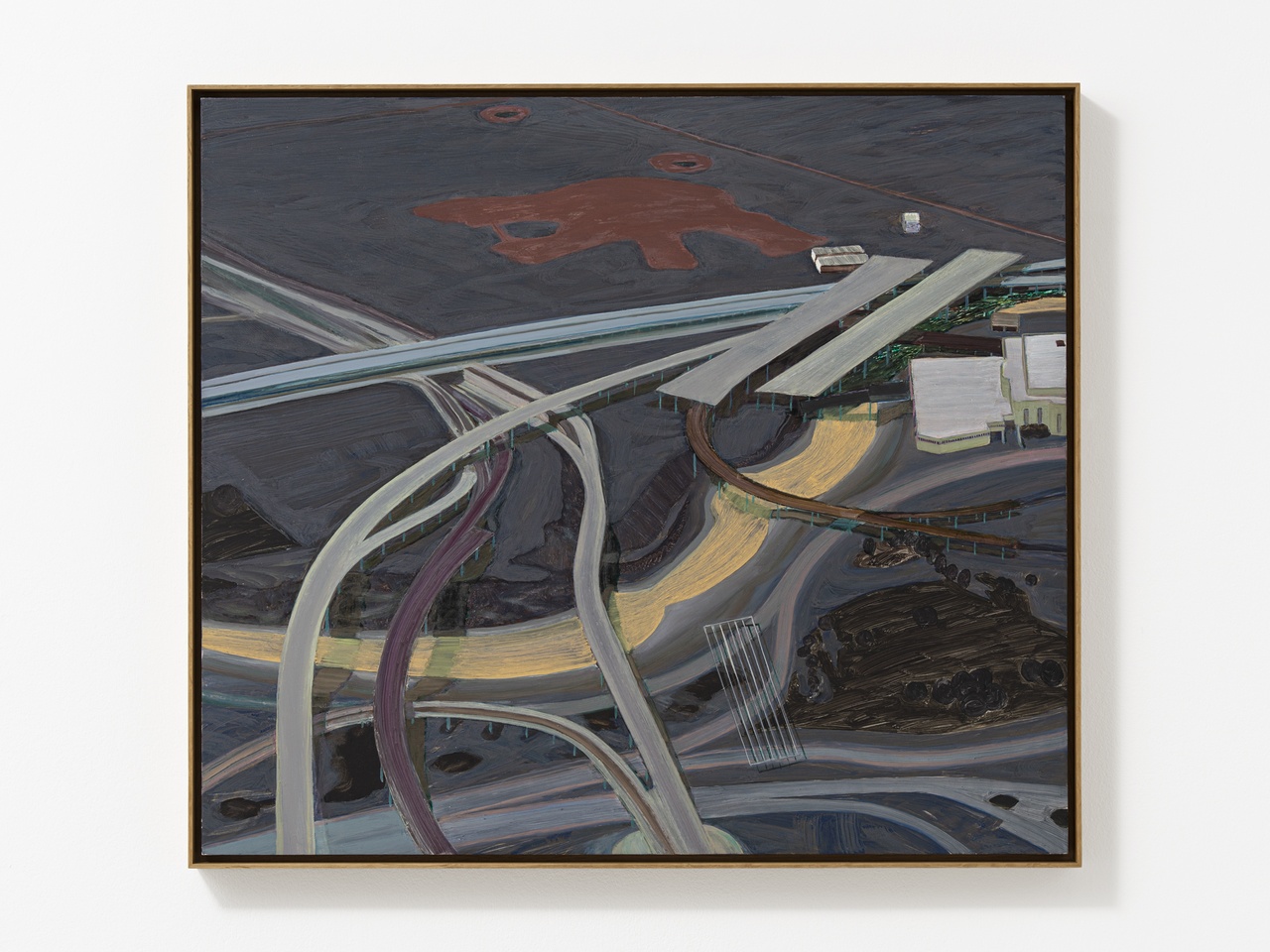

Carol Rhodes, “Surface Mine,” 2009-11

Fields are pierced, bent, and luminous; roads stretched thin; the boundaries of property splayed like a rotting circulatory system. In the work of Carol Rhodes (1959–2018) the thick, unbroken line of official record is a central component and dispute in her style: approximated but placed under significant duress. The abridged display of her work at Alison Jacques Gallery, comprised of nine oil-on-board paintings and five pencil-on-paper drawings dated between 1996 and 2013, all center on the archetypes of industrial landscape and their attendant environments. Roads, warehouses, stations, rivers, compounds, hills, and mines are delicately figured and demarcated. The form, however, is not of photographic deference or likeness but deliberate visual indeterminacy: dense, anti-pastoral, synthetic.

Rhodes lived and worked in Glasgow for most of her life, and a clear line of influence on her work can be traced via the “occasional exhibiting space” 42 Carlton Place, which she established with fellow painter Merlin James. Showing the work of Christina Ramberg and Prunella Clough among others, Rhodes likewise studied a particular object that was subsequently flattened, mutated, and compressed into frame. It is easy to read in this method an ambiguity or vagueness in the treatment of its subject: allusion instead of direct address. At times the perspective seems to slide out of place. It is unclear if a road’s angle indicates if it is traveling north or south, or is simply a stray line. A piece of metal or a stack of coal indents or seems to float above the painted plywood. At first glance, Rhodes insists upon the particular and contingent only for their arrangement and execution to reveal an impossible-to-maintain unity. And furthermore, as the “natural” units – hills, valleys, rivers – constitute as much importance as the industrial in each picture, topographies are not overwhelmed by one or the other but are instead congealed together and mutually deadening.

Carol Rhodes, “Coal,” 2008-09

In River, Roads (2013) an asymmetric and overlapping arrangement of roads and buildings exemplifies the fictional compositing Rhodes employed, taking from sources such as textbooks on geography, geology, and urban planning, along with photographs she took herself. As if reconstructing a crime scene, elements are appropriated and marginally adjusted: color, scale, and texture, but framed, cropped, and stretched in order to elucidate a paradoxically clearer, unreal image. Stubbornly aerial, each work surveys and indexes the particular components of an ambiguous, historically temporary process. The building to the right could be a depository or a station, and just below it a forest, or perhaps a dense raw material. The pictures focus on the usually unmemorable processes of construction, transport, and maintenance, while refusing the specific logics of their design or giving in to any elegiac refrain.

Images of capital and images of production are, at their root, a question of ordering: discerning hierarchies, fumbling with questions of scale and causality. A whole subgenre of photography and film is committed to “revealing” or “mapping” the supposedly clandestine operations of the state and/or commerce: a methodology propped up by going into Marx’s “hidden abode of production.” [1] These are artworks constituted by clean lines, diagrams, and neat conclusions. And yet by importing this methodology, the same miscalculation is carried over. That is, the impression that capital acts as “a coherent ordering of things,” and as such, the secrets of its world can “be discovered with arithmetic means and certainty.” [2] Capital, tout court. These paintings are not that strict record, though Rhodes’s concern over the arrangement between soil, water, tarmac, coal, etc. is clearly evident, as well as her commitment to rendering their idiosyncratic surfaces. Each picture is also not a banal accountant’s list of materials but a haunted, unpopulated rendition of a specific enclosure and its paradoxically indefinite endpoint. Or, put differently, the strict empirical limits and associative impasse of the subjects Rhodes chooses to paint are discarded in favor of expressing the internally fucked up and endless rearrangement of the living that they actually constitute.

Carol Rhodes, “Industrail Landscape II,” 1998

As if to further distance paint from object, the color is exaggerated, muted, or replaced, testing the limits of what truthful transcription should, or could, constitute. The earth is a murky gray-black, the river nuclear yellow, and a shape that resembles a figure stenciled into the field at the top of the painting a maroon-red. It is easy to reach for the apocalyptic here, but this is not a dystopia yet to arrive; it has existed in Britain for a long time. The colors used seem closest to those found in photographs of industrial slaughterhouses or rare earth mines, in which mile-wide pools of blood and ammoniacal nitrogen gather. But in the application of paint, such as in Surface Mine (2009–11), a green is revealed under the yellow of a field at the top of the painting, and a fleshy pink runs up the middle section. An affinity of color and shape that, due to Rhodes’s placement and marking, could indicate both or neither: grass or cadmium, flesh or roadwork. The paintings are also remarkably flat, wiped and sanded to almost a single layer. Road and Valley (1999) provides enough cues and depth to suggest a raised road to the left-hand side, cutting down through a darkened landscape with a river or a valley (or raised train track) to the upper right. But the perspective is flattened as if to make each part equivalent, unified, and unbalanced by the inconsistent black – a fragile appearance that simultaneously outlines the actual instability of production as well as its inevitable reordering. This precariously balanced collection of elements is held together as much by the surface treatment of Rhodes’s materials as by any observed object of study or physical continuity.

The skeleton of this project is revealed in Rhodes’s drawings, initially made in preparation for her paintings but eventually displayed in their own right. In Compound and Slope (2008) the building complex placed in the center – from which tendril-like pencil lines extend in all directions, denoting partitions and arbitrary designations – gives draft form to what is built up and further investigated in oil. In the bare white planes are the faint rubbed-out sketch marks of previous versions, redolent of what may have once been concrete. Like a photograph that has been double exposed an infinite number of times, or as if drawn on discarded plans.

Carol Rhodes, “River, Roads,” 2013

These works, then, depict not only a simplistic cartography but the historical and symbolic depth of inscription contained in such a process. For property cannot be understood through diagrams and documents alone. It is an impossibly violent form. And unlike the various categories of records, reportage, and photography, these works will never be useful in a process of forming correct definitions. It is precisely in this refusal that Rhodes’s pictures declare an apocalypse that is permanently unraveling and recurring but is never absolute.

“Carol Rhodes,” Alison Jacques Gallery, London, April 30–May 29, 2021.

Dan Ward is an artist and writer based in London.

Image credit: Courtesy of Alison Jacques Gallery, London