TRANCE, TRAUMA, DRIVE Beate Söntgen on Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen’s study on the modernist visualization of the human disposition

Vaslav Nijinsky, „L’Après-midi d’un faune“ (The Afternoon of a Faun / Der Nachmittag eines Fauns), 1876

The table of contents of Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen’s book Modern Art and the Remaking of Human Disposition (2021) alone is auspicious. It charts an unexpected constellation of artistic works from around 1900 through a diverse range of genres and media, from Georges Seurat’s paintings to the Vienna Secession’s Beethoven exhibition all the way to Vaslav Nijinsky’s dance L'Après-midi d'un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun, 1912). The pose that painted and living figures assume in artistic works and performances is the book’s thematic frame. Exemplified by their frontality, poverty of gesture, and lack of expression, Butterfield-Rosen reads these fin de siècle poses as the visual articulation of a new understanding of the human disposition. Not thinking or feeling but rather automatic impulses and the unconscious mind outside our control come to the fore in these representations – representations that, through the intermingling of human and animal, underscore the philosophy of that time, scientistic psychology, as well as psychoanalysis.

The grievance inherent therein, that man is no longer the intellectual crowning jewel of creation, no longer “master” in his own house, as it was so aptly put around 1900, is also reflected in the period’s critical reception of the works: it bemoaned a form of existence being brough to view that, instead of depicting rationality and sensitivity, was dull, rigid, animalistic, and, indeed, not the slightest bit intellectual. The frontality of the figures was the artistic device par excellence, according to Butterfield-Rosen, and yet not in the spirit of a modernist reading in which frontal figure representation is viewed as a milepost on the high road to abstraction. Rather, Butterfield-Rosen sees frontality as an artistic response to the imperative that the depiction of psychological interiority be brought up to date with the insights and theories of the time.

The author expands on this by looking at the rhetorical concept of the figure: in current usage, it denotes a form through which a thought is expressed and is thus in keeping with the idea that intellectual ability distinguishes the human subject. Western art’s centuries-long striving for variability and liveliness in the depiction of the human disposition was transfigured around 1900 into the very opposite, namely into striving for stiff, unmoving, frontal postures, as had been done in ancient Greece. In this way, the figures became figurae in the original rhetorical sense, namely the expression of a deviation from the norm, in this case from the demand for artistically rendered aliveness, which again was considered to be the expression of distinctively human faculties, most especially the creative power of the intellect. One of Butterfield-Rosens’s most fruitful methods of exploring the historicity of objects is to retrace the changing meanings of words.

The three sections of the book, each of which is dedicated to one of the artistic positions mentioned at the beginning, can also be read independently of one another. However, it is through this constellation that the multifaceted nature of these new insights into the human condition as well as the implications they hold for art, the history of knowledge, and society are most clear. Butterfield-Rosen considers posing – the attitudes made evident through poses – under the rubric of disposition: a term deliberately selected for its proximity to the rhetorical figure of dispositio in addition to Michel Foucault’s dispositif. According to the working hypothesis, poses are formal mechanisms through which each of the discussed works transmit to their audience various types of knowledge about the inner state of the subject. The author understands the artistic works as theoretical objects, to use Hubert Damisch’s words, that oblige their observers to grasp theory while at the same time providing them with the means to do so.

How this is to be understood is brilliantly demonstrated by Butterfield-Rosen. She develops her theses by means of a concise examination of the works, especially of frequently overlooked details, and by analyzing contemporary art criticism as well as scientific and philosophical approaches. In this way, the study illuminates the relationship between historical conceptions of the psyche and the formal logic of the artistic works.

Geores Seurat, „Les Poseuses“ (Models / Die Modelle), 1886/88

Georges Seurat is an ideal opener. Few other works from the period so clearly emphasize the new conception of human disposition as Les Poseuses (Models, 1886/88) – at least once the author has sharpened our vision. Drawing on Giorgio Agamben, she points to a “loss of gestures” around 1900, correlating with an obsessive preoccupation with gestures at the same time, as in Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. The sudden shift from expressive gestures to illegible postures is evident in Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass, 1862/63), where empty body language attests above all to the unsuitability of traditional forms of communication within the pictorial as well as with the viewer. It would have been illuminating to compare the specific form of the frontal that had already been employed by Manet as a means of defying the postulates of aliveness upheld by the art academy with the specific form of frontality that was used in art around 1900.

Seurat also invokes the repertoire of classical poses, albeit in a self-referential studio scene that makes posing its theme. And not only that. With Les Poseuses, Seurat is also responding to the criticism made about his painting Un Dimanche à la Grande Jatte – 1884 (A Sunday on La Grande Jatte – 1884, 1884/86), which had been faulted for the rigidity and lifelessness of its figures in particular. A section of the painting also appears in Les Poseuses, in fact, the very section that had been criticized most harshly, namely the section featuring the lady depicted in stark profile with a cul de Paris and a little monkey. The monkey and the woman both mirror each other’s posture, a relation by which imitatio in art coalesces with mimicry in fashion and the consumer world – a coalescence that also suggests a resemblance between human and animal modes of behavior. After all, it is the monkey that symbolizes the imitative impulse in art, for example in caricatures, an impulse also governing fashion, which is largely represented by women.

By returning to sophisticated, large-scale figure painting, Seurat reinstates the anthropocentric academic tradition, only to simultaneously disavow its ideal of the highest measure of life, namely life invested with intellect, and not only through the analogy of the ape and the fashionable woman. La Grande Jatte is shaped by a rigid, repetitive, crude mode of representation, which critics disparaged accordingly. The hieratic forms were celebrated by a few admirers as a new “primitivism” that also brought out the creature-like nature in man. In Les Poseuses, Seurat offsets the rigidity of the figures in La Grande Jatte by quoting classical poses that suggest gentleness, charm, and contemplation.

The central figure in Les Poseuses assumes the pose of a famous classical Greek statue of Demosthenes, which, as the very embodiment of the intelletual activity of a thinking subject, is regarded as the first psychological portrait. Butterfield-Rosen reads the inversion, both gendered and mental, of the painted figure against the backdrop of the women’s movement, the image of the new woman, and the hysteria experiments: in her trance-like posture, the central figure, now a penseuse, is transformed into a parody of the supreme being. Yet the author herself doubts whether a feminist reading will hold water. For it is not only in Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, the Parisian psychiatric hospital, where the female body becomes the male-dominated spectacle of an unconscious automaton, but also in the studio. Butterfield-Rosen reveals an ambivalence formative in Les Poseuses by investigating the concept of katalepsis and its semantic shifts. Katalepsis describes trance-like states, and in its original sense refers to understanding and grasping. It is also this twofold meaning of active comprehension and an unconscious dawning that the author sees in the iridescent gaze of the central poseuse. Through the posture of Demosthenes, the figure demonstrates what she is, a model in the studio, tired after posing so long, and aware of her social and economic situation, and yet, at the same time, she gazes into emptiness, remains expressionless and closed. The question asked so vehemently around 1900, namely, what is thinking – in other words, what sets apart the highest species, which at that time was seen as the human – is here being answered with a Kippfigur, a visually ambiguous figure: thinking does not appear to be a sovereign act, as it had traditionally been depicted since antiquity in poses with the head propped up in contemplation or with the brow furrowed through the effort of thinking, but instead alternates here between the conscious and the unconscious.

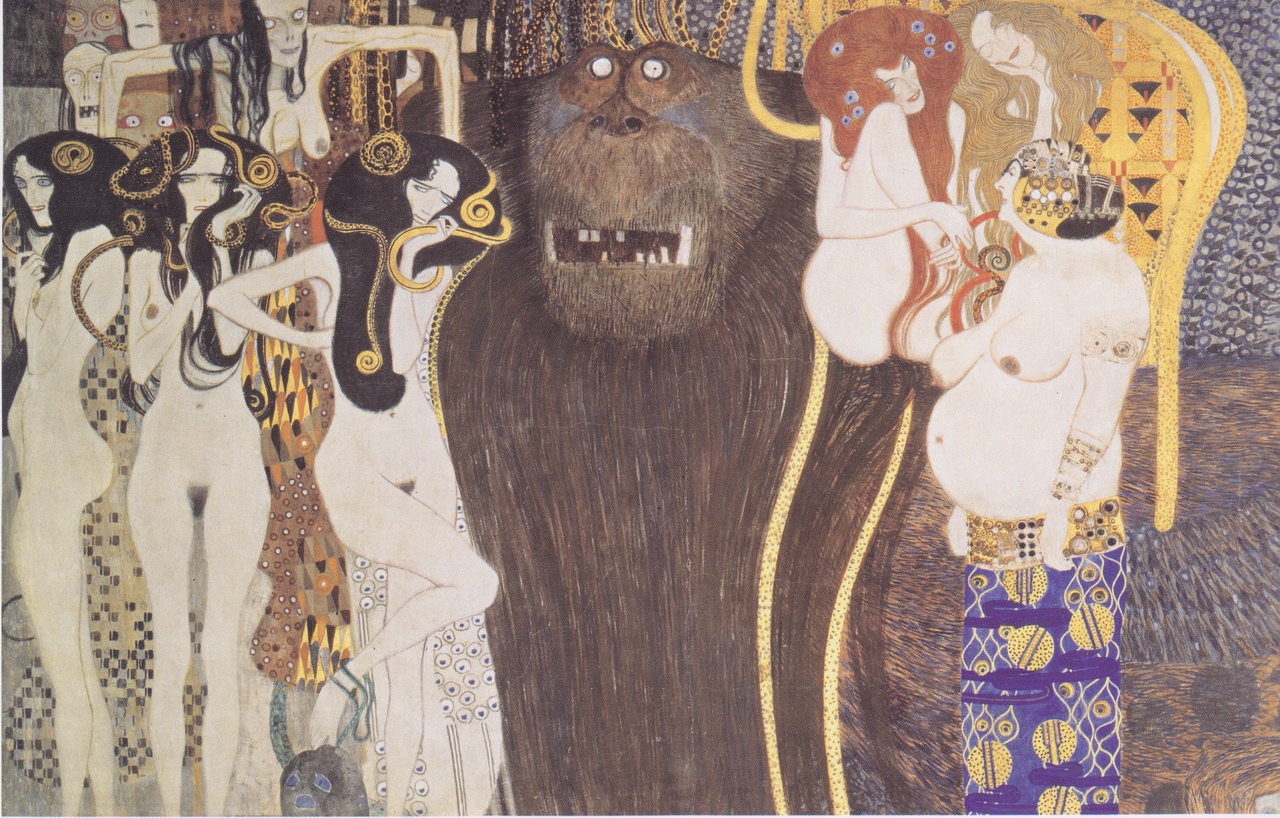

Gustav Klimt, „Beethoven Frieze / Beethovenfries (The Hostile Powers / Die feindlichen Gewalten)“, 1901

The role that the emerging psychological and psychoanalytical sciences had assumed is succinctly illustrated by Butterfield-Rosen with the Beethoven exhibition at the Vienna Secession in 1902. Here, once again, the whole array of creator myths is trotted out in Max Klinger’s monument to the composer: in a posture of masculinity, intellect, and genius, Beethoven sits enthroned, shimmering between the hieratic and the classical. What undermines this posture and the notion of the creative, inspired genius that goes with it are the decorations on the wall, which strip the central figure of his power through the proliferating ornamentation. It is Gustav Klimt’s contribution, in particular, that presents eroticism and sexuality in place of the intellect as literal drives, which are almost animalistic, as evidenced by the sperm-shaped ornamentation and the golden monkey heads. However, as Butterfield-Rosen illustrates in comparison with Auguste Rodin, the connection between sexuality and the act of creation should not be understood on analogy with ejaculation, giving birth to fertile thoughts and bringing forth the corporeality of thought. What reigns in the Beethoven monument is the “spirit of gravity” so ridiculed by Friedrich Nietzsche, which the figure’s seated position ultimately reenforces. Klimt’s rendering, by contrast, conveys the experience of fluidity and effortlessness, evoking an unconscious realm of life. Again, the author works with the literal and metaphorical meaning of the critics’ own words while making precise iconographic observations, for example within the domain of grasping and gravitas. It is the hand and finger gestures of Klimt’s paradise angels that meet the fist of the sculpted Beethoven with Buddhist connotations of openness.

The sexual as a regressive drive, which also reigned in the arts, finds its culmination in Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreographic adaptation of Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, 1894), a musical evocation of Stéphane Mallarmé’s related poem from 1876, precisely through the rigid poses held in frontal or sharp profile, which entail the cessation of movement in, of all things, dance. And citations abound here, too, this time taken from Greek vases. The leitmotif is the erect position of the faun’s arm and hand, an unambiguous display, to both the retreating nymph and the shocked audience, of his desire to penetrate. Sexual union does not take place, and the faun must be content with himself. As a late autobiographical account attests, the fact that Nijinsky was deliberately tapping into the contemporary interest in the then recently identified topic of infantile sexuality, as first addressed by Sigmund Freud, evident in the stage directions: the nymph was to be considerably taller than the petite faun, whose piebald costume underscores his animal nature.

Through both precise analyses of iconography and the history of discourse, Butterfield-Rosen brings out the interplay of masturbation, exhibitionism, and voyeurism which is made visible by Nijinsky’s mise-en-scène, while also mirroring the audience. Everyone does it, is the message, unbearable in its visibility, that the piece conveys. Dream work and artistic representation meet, as Butterfield-Rosen argues, in an attempt to give expression to the unconscious, to the psyche as an apparatus dominating the human disposition.

Not all aspects of this multifaceted study can be recounted here. Within intelligently laid out theoretical frameworks, the author illuminatingly brings social and discourse history, reception aesthetics, and visual studies together. The theses are convincingly elaborated through an intensive examination of the material. That the historical study’s interrogative horizon is grounded in the present is as apparent in its discussion of “primitivisms” as it is in the attention paid to the problematic implications of the term posthumanism, which despite a critical perspective still retains its reference to European humanism. The study leaves nothing to be desired in its intellectual reach, in the precision of its observations and argumentations, and in its lucid, descriptive presentation.

Emmelyn Butterfield-Rosen, Modern Art and the Remaking of Human Disposition, University of Chicago Press, 2021, 352 pages.

Beate Söntgen is a professor of art history at Leuphana Universität. She is the spokesperson for the DFG research training group “Cultures of Critique” and headed the project “PriMus – PhD in Museums” with Susanne Leeb. Her current research project on “Artistic Life as Intervention” is part of the “Intervenierende Künste” reseach group at Freie Universität Berlin. Her research areas are art, art theory, and art criticism of modernism and the present. Most recently, she coauthored the reader Why Art Criticism? (Hatje Cantz, 2022) with Julia Voss.

Image credit: 1. Public domain, 2. Public Domain, Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia; 2. Public domain, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna