AN INHERENT FEELING OF PERIL Hugo Bausch Belbachir on David Armstrong at Kunsthalle Zürich

“David Armstrong,” Kunsthalle Zürich, 2024

After David Armstrong’s death in Los Angeles in October 2014, many of his friends recalled the significance of his voice. A cadenced voice they described as deceptively docile. A mother’s voice that, as his friend Jack Pierson put it, could “comfor[t] a child she is preparing to suffocate with a pillow.” [1]

Another friend, Wade Guyton, made his way to the late artist’s studio in Massachusetts. There, he recovered a few boxes brimming with hundreds of photographs. These images from the 1970s onward, the result of Armstrong’s relentless artistic pursuit, had remained mostly unseen. Folded haphazardly, stacked in defiance of reverence, some torn, as if bearing the weight of forgotten time. Guyton brought them to his studio in Brooklyn, where he, together with Colleen Doyle, spent ten years carefully archiving this fragile legacy. The viewer cannot be certain whether Armstrong intended for all of the works to be presented: if some were merely studies, or if others were outright discards. Guyton, too, cannot know. Nor can Daniel Baumann, cocurator and Kunsthalle Zürich director. Nonetheless, they are all exhibited and accorded equal significance, each encased in a sort of uniform (an elevated white frame) that imparts a sculptural dimension to them, emphasizing the subtle undulations of the paper on which they are printed. This curatorial decision responds to the posthumous complexity of a work about which very little has been written. A kind of mystery, epitomized by the strangeness of an artist’s voice and intrinsically linked to his biography. In this regard, the first institutional exhibition dedicated to David Armstrong seeks to uncover a personal history – one that begins in Boston, at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, with Armstrong’s companions, and then takes place in Provincetown, and, finally, New York, at the Mudd Club and other venues, culminating in his fashion works from the 2000s (these later works, although referenced, have been deliberately excluded from the exhibition selection). The show delves into nights spent together in student dorms. Nights filled with drug use and free-spirited sex – preceding the era of conscious everything. Nights spent dreaming of making films, becoming famous, and engaging in political activism. It presents portraits of the cursed geniuses in the artist’s orbit: poet René Ricard, writer Gary Indiana, beloved friends Nan Goldin, Christopher Wool, and Cookie Mueller, and countless others.

The works in the show were produced between the 1970s, when Armstrong oscillated between Boston and Provincetown, and the 1980s, when he settled in New York. They are anything but romantic. Better described as possessed. Possessed as in alive forever, despite many of these figures having died from AIDS and drug use, like Mueller, whose portrait Cookie at Bleecker Street, New York City (1977) opens the exhibition, facing – or even intimidating – each viewer as they enter; posed on a chair against a wall, her eyes slightly downcast and torso angled forward, she places her hand behind her neck, perhaps running it through her hair, in an attitude tinged with irreverence. A specter of the real world – that of Armstrong’s intimate circle of friends, lovers, and colleagues – echoing these words from Mueller herself: “Actors wait on tables, ballet dancers work as topless go-go girls, artists wash dishes, and that’s not even the worst part. Someday you might bring your garbage on the subway, someday you might even shit in your own bank.” [2]

David Armstrong, “Cookie at Bleecker St., NYC,” 1977

The presentation is structured in two parts: the first focusing on portrait photographs, and the second dedicated to the blurred landscapes Armstrong began producing from the late 1980s onward. These are accompanied by a selection of 300 contact prints. At the end of the exhibition, two monitors – one positioned vertically and the other horizontally – display a selection of color snapshots taken in 1979 during a trip from New York to Provincetown. Shot in club and bar settings on colored film and using a flash, the portraits of these early years formalistically align with those taken by Goldin at the time, and even feature some of the same subjects. Bea Roger (Bea, Boston, mid-1970s), for instance, was Armstrong and Goldin’s roommate in Cambridge in the 1970s. It was largely for this reason that Armstrong distanced himself from this aesthetic attitude early in his career, seeking to distinguish his work from Goldin’s and concentrating instead on black-and-white photography, primarily portraits, and using natural light. Also during this period in the late 1970s, Armstrong started to invite several friends to pose in his Elizabeth Street apartment in New York. Amongst them were his boyfriend Chris Hameon (Chris at Elizabeth Street, New York City, 1979), a model also known as French Chris; Suzanne Fletcher (Suzanne at Elizabeth Street, New York City, 1978), Armstrong’s lifelong friend whom he met in second grade in Lexington, Massachusetts; and artist Christopher Wool. They are captured with a medium-format camera, seated, at rest, bathed in the light coming in through a window. Unlike the earlier snapshots, these photographs stand out for their carefully composed nature that would set the tone for the remainder of his oeuvre.

There is an essence of danger woven into David Armstrong’s portraiture. An inherent feeling of peril that is palpable in the desire the images embody. A danger that coincided with the AIDS crisis, which claimed most of his friends. A danger (never fantasized, but experienced) that encompasses the exquisite tension of the body at its limits; the torrent of love, sex, and the lost that comes with it. Look at Kevin (Kevin at St. Luke’s Place, New York City, 1977), who became Armstrong’s first boyfriend upon arriving in New York after they fell in love in a club in 1977: portraits of him are a concentration of love and pain; they record his physical transformation as he succumbed to AIDS, shifting from portrait to portrait and culminating in his final, almost unrecognizable, image (Kevin at Avenue B, New York City, 1983), taken just weeks before his death at the age of 24. An adoration of beauty and a defiance of what constitutes the ordinary is present as well in Armstrong’s images. While visiting the exhibition, I cannot help but notice the Proustian sumptuousness of the portrait of René Ricard (René at His Apartment, East 12th Street, New York City, 1979), delightfully sprawled on his bed in his apartment. Dressed in a white leather coat with its collar partly turned up, Ricard casts a gaze both complicit and cursed from below. So does Andrew (Andrew as a Sailor, New Haven, 1996), whom Armstrong met in Berlin in the early 1990s.

“David Armstrong,” Kunsthalle Zürich, 2024

The second part of the exhibition emphasizes this loss as one that lingers in the landscapes left behind. The selection of soft-focus landscape photographs stands for a body of work Armstrong began producing in 1992 during a trip to Berlin, where he was visiting his friend Goldin. He continued creating these photographs upon his return to the United States and throughout the remainder of his life. As Wade Guyton and Daniel Baumann note, the landscapes

David Armstrong was a photographer of the anti-hero: of the punk, the cursed poet, the sex worker, the lost, and the loner. Those who define themselves against the normative myth, or at the very least, who exist within the irreverence imposed by such myth; its conformity, its fear of desire, and its disdain for everything outside its limits. By consistently photographing his subjects indoors – with the notable exception of some shots taken on the beaches of Provincetown – Armstrong built a body of work (further extended in his fashion photography) that reveals itself within the secrecy of an interior; in a place insulated from the normative myth.

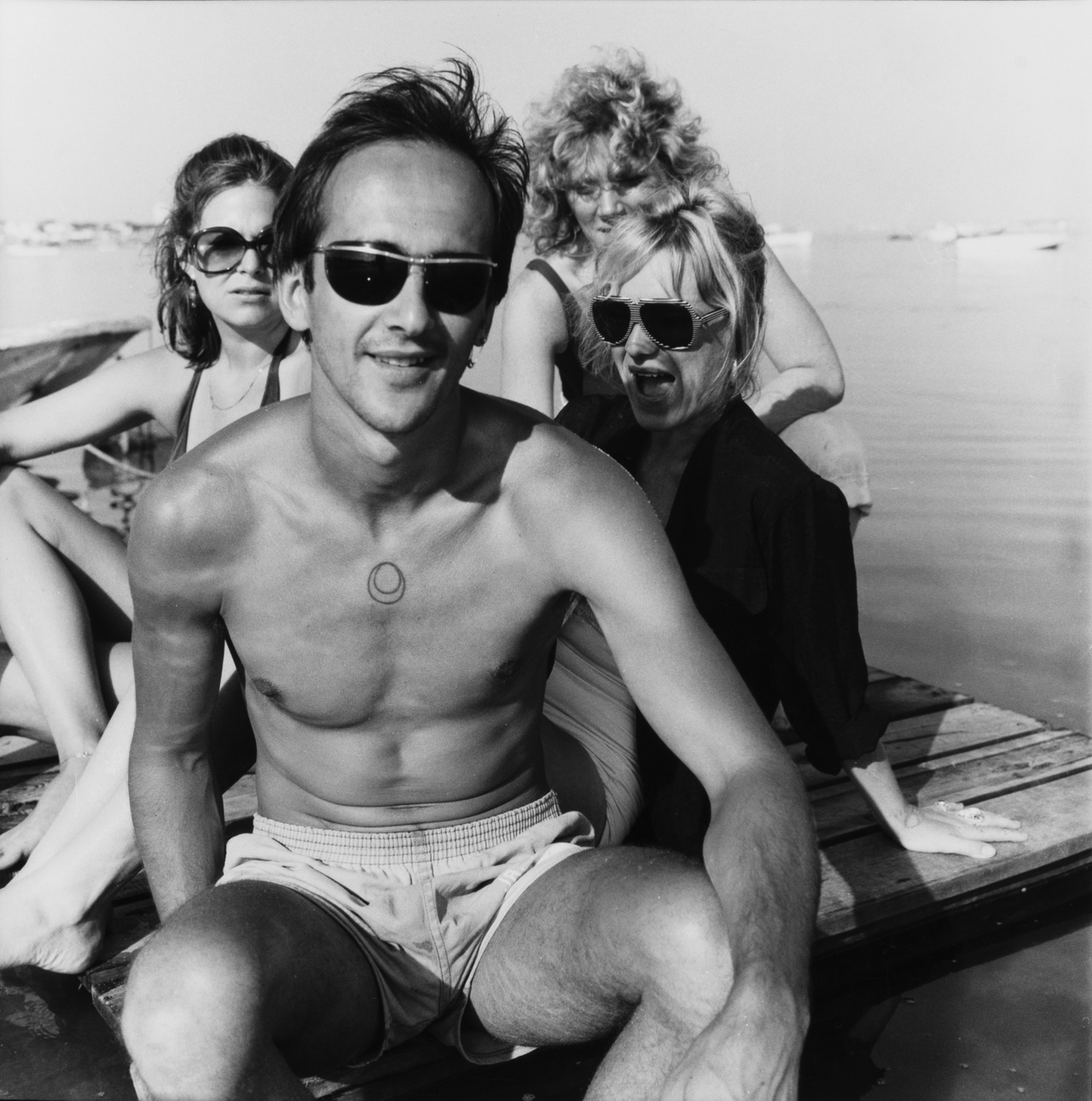

David Armstrong, “Bruce, Cookie, Sharon, and Linda at Herring Cove, Provincetown,” late 1970s

What is ultimately important to grasp from this exhibition is that, compared to photography, no other medium has succeeded in offering such a clear critique of this myth – the myth of America, of the bourgeoisie, of normative sexuality, of the imperative to labor, and of submission. These critiques are evident in the works of Weegee, Robert Frank, Walker Evans, Larry Clark, and Diane Arbus, among others. No other medium has articulated this with such directness, and it is crucial to emphasize the profound importance of the group –simultaneously connected and distinct – formed by David Armstrong and Nan Goldin together with Mark Morrisroe and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. [4] The crucial difference lies, nevertheless, in the fact that, unlike Arbus, who ventured to New York’s Washington Square Park to photograph figures she considered “freaks,” Armstrong, much like Clark, photographed his friends, lovers, and all those with whom he intended to share his life.

In ever new forms, American photography has depicted the individual as an outsider, and photographers have often considered themselves independent, et d’une certaine manière supérieure from the situations they depict, observing these contexts from a position of the brave explorer – akin to the act committed by the anthropologist venturing into regions of unknown cultures. David Armstrong, however, developed a practice rooted in his own participation, never positioning the margins of any context as spaces from which he stood apart, and always understanding them as integral to his own existence.

“David Armstrong,” Kunsthalle Zürich, June 8–September 15, 2024.

Hugo Bausch Belbachir is a writer and curator based in Paris, France.

Image credits: 1. Photo Cedric Mussano; 2. Courtesy of the Estate of David Armstrong; 3. Photo Cedric Mussano; 4. Courtesy of the Estate of David Armstrong

Notes

| [1] | Jack Pierson, “David Armstrong (1954–2014),” Artforum, November 19, 2014. |

| [2] | Cookie Mueller, “Another Boring Day,” Ask Dr. Mueller: The Writings of Cookie Mueller (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1997). |

| [3] | Wade Guyton and Daniel Baumann, David Armstrong, exh. cat.(Zurich: Kunsthalle Zürich, 2024). |

| [4] | In 1995, the exhibition “The Boston School,” organized at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, was the first exhibition to consider a common denominator between the work of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia, Nan Goldin, Jack Pierson, Mark Morrisroe, and other artists from the Boston suburbs between 1975 and 1985. See Lia Gangitano and Milena Kalinovska, eds., Boston School, exh. cat. (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1995). Though it is now manifest that this group only ever existed as a myth – Armstrong and Goldin having already left the School of the Museum of Fine Arts when Morrisroe and Pierson arrived, and the legend being only assumed much later, in the 1990s – this quintet nonetheless came to symbolize a photographic historical context marked by a crucial recognition of friendship, desire, and death. |