DAN GRAHAM (1942–2022) Nicolás Guagnini

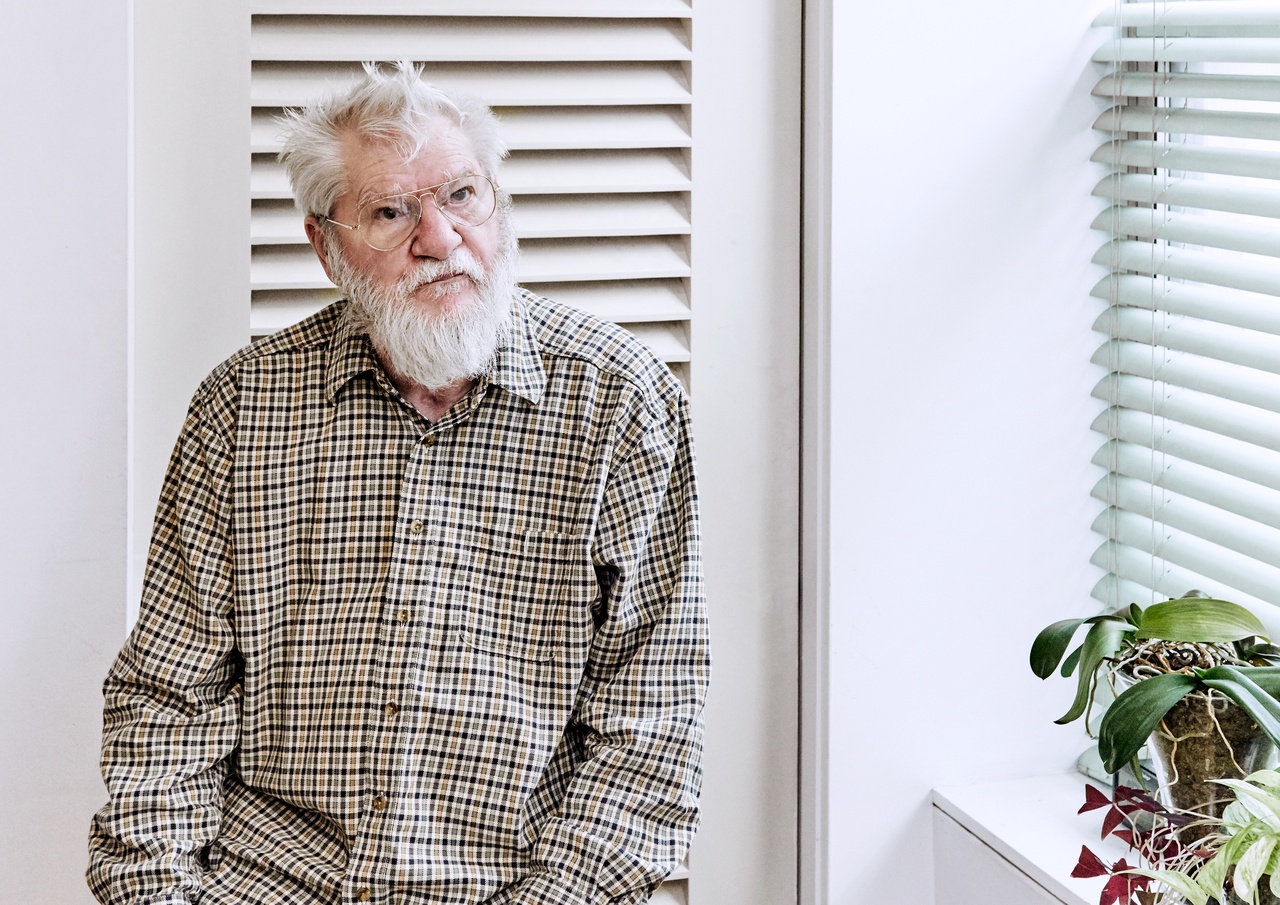

Dan Graham, 2018

LUNCH WITH DAN

During 2007 and 2008, in the time leading up to Dan’s big retrospective in the United States, Dan and I had lunch about once a week. Retrospectives, understandably, freak artists out. For Dan, any fantasy of outsiderness was being dissolved. He was engaged in a raging battle with the curators over many aspects of the exhibition, but whatever the negotiations were, or were not, he did gain important control over deciding the catalogue’s authors and contents, which featured interviews with artist friends. Ours was to be a distilled version of a public talk we did in 2006. The section of the talk that was ultimately published concerned Dan’s work in magazines. Not only was Dan in full disavowal mode of prior critical reception itself, but the focus was on conceptual art, to which he ascribed the now often-quoted characterization of “academic bullshit.” Besides and beyond the incendiary aspect of this pronouncement, what transpired in our public talk was the core of Dan’s argument: the replacement of objects by ideas could not exist without a social system of communication, namely magazines, and that system was full of contingency, context(s), and had a historical form and function. His was an argument against autonomy.

The talk was to be edited by me and the curators/editors. Dan acted, as usual, as a meta-editor. It was futile to bring an agenda to conversations with Dan. Astrology, current events, interpersonal stuff, history, and art proceeded to parade in a sort of rhythmic windmill. Three things were certain: there will be one or two irate moments and a raised voice, there will be one or more personal or cultural insights of lasting and penetrating power, and there will be humor and affect. Such were the circumstances and the conditions for these lunches.

We met at Cafe Habana, a hip, inexpensive Latin-themed burgers-and-tacos outfit around the corner from his Nolita home and studio. The place was always full of beautiful young people working or consuming in the independent fashion shops that populated the neighborhood, and next-door, it had a small, fast-paced space for take-out with two tables and a window counter. We retrieved our burgers and miraculously got one of the tables. Dan vehemently struggled with a ketchup packet, pressing it with such force that somehow an ultra-thin stream shot up to the low ceiling, where it created an upside-down bloody pool. While I helped Dan with another ketchup packet, which he proceeded to spread on the burger and his beard, I realized everyone was looking at us. I was mortified. Yet, the two Mexican guys charged with the infernal job of manning the grill were clearly enjoying the anarchy of the situation; and the two Dominican women who were at the cashier and the tray and packing station, and who would no doubt be in charge of cleaning up our mess, were equally amused at our thrashing about the joint.

Dan took an ample bite of his burger while I quizzed into my drink. Still munching, he uttered: “Your mother became a psychoanalyst because she was a failed artist. She put so much pressure on you to be a genius that you had to leave your country.” He of course had no information about my mother’s childhood and teenage ambition to become a concert pianist. He was spot on. Dan had the ability of producing, extemporaneously and violently, an interpretative insight equivalent to about three years of therapy in an expensive Upper West Side couch in a single sentence. I was flummoxed, and moved. The ketchup from the ceiling began to drip on the table. The situation was dire. I managed to clean a bit and position my fries under the disaster zone. A failure had at least become a precarious system. The hipsters looked approvingly at Dan’s Hawaiian shirt, his spiky white hair, his guerrilla beard, his half-punk, half-Miami-Jewish-retiree look. Dan owned the room, performing real-life comedy, and was oblivious to it.

I retorted: “Dan, it is you who is obviously a genius.” Wrong move. Dan burst into a long, loud, angry tirade about how he was a failure most of his life. I endured it silently, which further entertained the Latin personnel and the model wannabes. This concluded abruptly in a simple, blurted statement: “Balla is better than Picasso.” Still reeling from the psychoanalytic insight followed by the ritual screams, I tried to evade the polemics: “This is comparing apples to oranges. They are both great in their own way.” Dan pressed on. There was no changing pace or subject. “Balla’s conception of space as time is much more advanced, Picasso’s is just classical; Balla has humor … have you seen his poodle painting? It’s about middle-class ladies walking their dogs; Balla evolves into banal decoration, Flavin’s highest value; Picasso is always full of bulls and naked women instead. Balla has range. He let Boccioni take the lead and became a funnier artist.”

The message has been conveyed, the discussion has been had. “Genius” is the enemy, range is the goal. The interview for the catalogue must very clearly differentiate Dan from Weiner and Kosuth.

A DREAM ABOUT DAN

The night after Dan died I dreamt I had to call him and tell him about his death. I woke up rattled, confused, and for most of the day feeling incredulous about the impossibility of making the call. I rationalized the nightmare somehow as just grief. A few days later it became clear. It contains Dan’s core lessons: time is not linear, the subject is not unified.

Nicolás Guagnini is an Argentine born, New York-based artist and writer. He is a Saggitarius in the western horoscope and a Horse of Fire in the Chinese horoscope.

Image credit: Andrew Boyle