A CRAB DOES NOT GIVE BIRTH TO A BIRD: NII KWATE OWOO ON HIS FILMS AND FORMATIVE INFLUENCES An Interview by Jeanne-Ange Wagne

Nii Kwate Owoo, “You Hide Me,” 1970

JEANNE-ANGE WAGNE: Thank you so much, Nii Kwate Owoo, for taking the time for this conversation, which ties in with the current issue of TEXTE ZUR KUNST. That issue focusses on the topic of restitution, and your film You Hide Me (1970) is highlighted in an essay by Oliver Hardt. I had the pleasure to curate and coordinate the KuK Tuesdays “Dislocation” series at TU Berlin, and You Hide Me was screened as part of one of its events, hosted by Kino Arsenal last summer. You were present, and the screening was followed by a Q&A with the cinematographer Jide Tom Akinleminu. A lot of your film’s layers were peeled off during the interesting conversation between you and Jide. I would like to build on that and talk a bit more about your practice and how it has evolved. In recent years, you’ve been able to present and discuss You Hide Me on several different platforms and stages. Our conversation today, more than eight months after the screening at Kino Arsenal, is proof of the ongoing relevance of your film for the restitution debate. I would like to use the opportunity to contextualize your work and shed light on your artistic background. Let me begin by asking what role Ghana’s political history plays, not only in your life, but also in your cinematic work?

NII KWATE OWOO: I have to go back to my childhood in Accra. My late father, who is now resting peacefully in the arms of our ancestors, had a big influence on my development. When I was about four years old, he was a political activist and a chairman of the party of the late Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah, who became the President of Ghana after the struggle against British colonialism, which resulted in the declaration of our independence in 1957. My father was a very proactive Nkrumahist. I used to ride on his shoulders to political rallies. When I was still a toddler, he took me to most of the rallies that he attended or helped organize as part of the Gold Coast’s struggle against British colonialism. Subjectively, I believe that even though I was quite young, I was imbibing things, and I was being psychologically influenced by the cry for freedom and the way in which the masses at these rallies used to sing political songs. It was actually my father who set in motion my political development. And he was also a movie fanatic. There was a cinema, about five minutes walking distance from our house, called the Globe Cinema and he used to take me there to watch movies, every Friday, Saturday, Sunday. This was during the colonial period, in 1948. I was exposed to the big screen; many movie scenes are etched in my memory. Later on I realized that a lot of the films I saw were with Frank Sinatra, singing. I saw some action movies, too, but I was mainly influenced by these movies starring Frank Sinatra. I became fixated with the moving image and with the power it had on me. I sat on my father’s lap, and I didn’t fall asleep at all, watching the movies right to the very end.

WAGNE: Would you say that until this day, Ghana’s history and political development are at the center of your work?

OWOO: Well, in a way, Ghana’s history is the reason why I started this kind of work in the first place. I went to a very famous high school in Ghana, Mfantsipim School in Cape Coast. It was a very religious Methodist Mission School. History and art were my favorite subjects. And then, in the mid-1960s, my parents sent me to the UK to do my advanced level certificate in London. I did that and decided to stay and go to art school. My idea was to come back home to Ghana as an art teacher. But an unexpected incident changed my course.

WAGNE: What was that unexpected incident?

OWOO: I was on a train and realized that I had missed my station. Walking back to my intended destination, I came across a billboard advertising a television school. I followed the directions to the school and became so excited when I discovered that it was a television school that offered a three-month short course for foreign students. I was accepted and learned how to produce a TV program from A to Z. During that period, I spent a lot of time in London’s cinema houses. After I completed the television course, a friend told me about the London Film School. Since I wanted to make movies, not only television programs, I applied, was admitted, and studied the techniques of filmmaking and movie production. Shortly before graduation, I dropped by the British Museum on one of my walks through the city. The idea of making a documentary exposing the hidden and stolen and looted artworks from Africa was hatched in my mind during that visit.

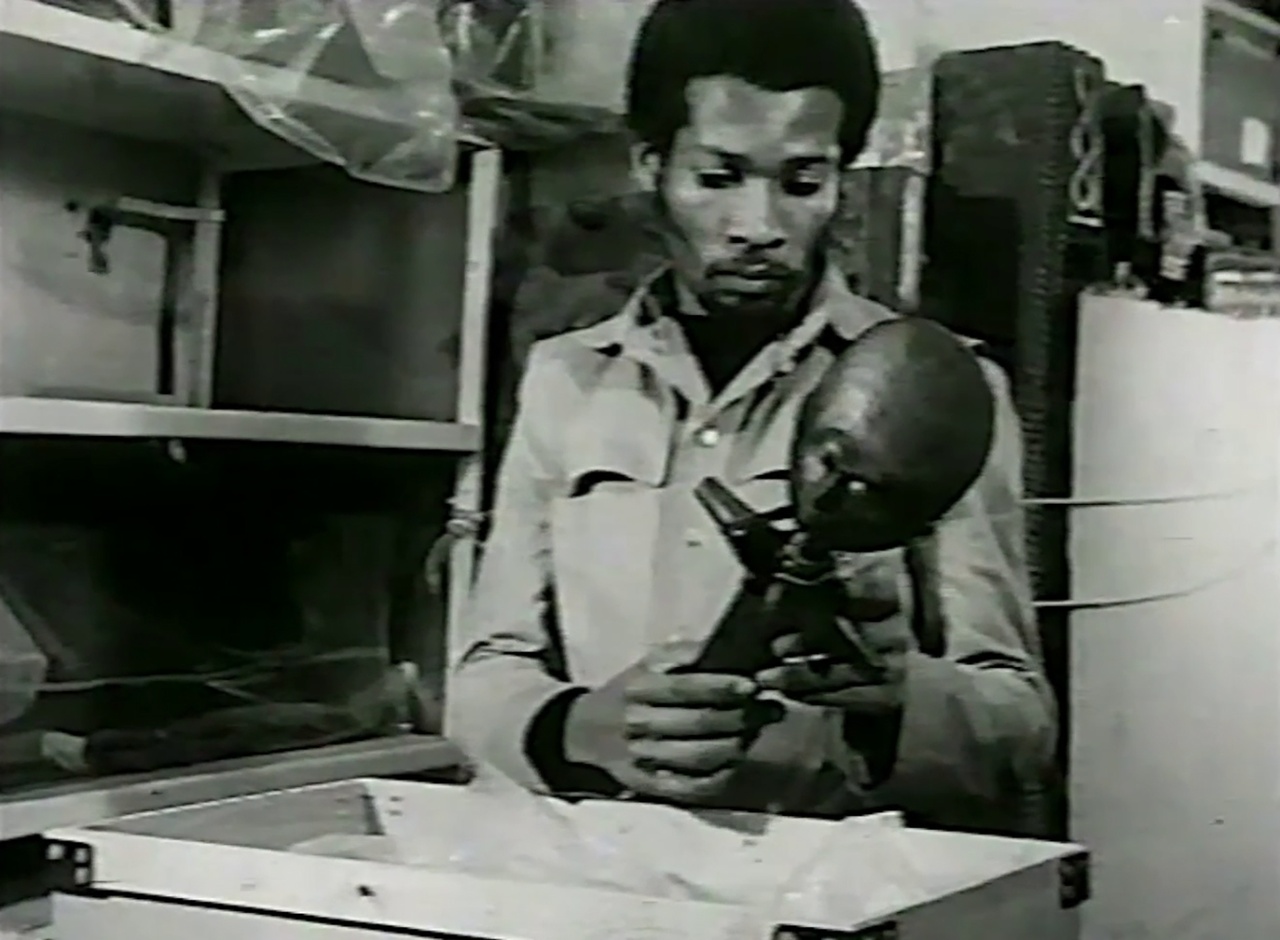

Nii Kwate Owoo, “You Hide Me,” 1970

WAGNE: In the preface to their current issue, TEXTE ZUR KUNST’s editors write about the very recent moment in which the return of material culture appropriated in colonial contexts has gained traction. Restitution has become a hot and pressing topic. But of course, debates around Africa’s translocated material culture are not new. Benedict Savoy addresses them also in her 2021 book title Africa’s Struggle for its Art. Do you recall from the 1960s and 1970s how present restitution claims and corresponding conversations were then, when you visited the British Museum?

OWOO: I had no knowledge of any restitution claims and debates at that time. Nobody had introduced me to any discourse around restitution, I was totally ignorant of it. I went to the British Museum because I was interested in history – in African history, to be precise. I just went there on impulse because I wanted to explore some ideas on African art. I was an artist.

WAGNE: You are indeed an artist, not a politician. I would say that your art is a form of research, but you didn’t attend art school and film school to become a researcher per se. I would be interested to know: Who are your cinematographic role models, or peers that you relate to?

OWOO: Cuban cinema had a major influence on me, politically and ideologically, especially the works of the late Santiago Álvarez. While I was in England, the Vietnam War was raging – it was on television all the time. I became a member of a Black political movement in London called the Black Unity and Freedom Party. And through this movement, I was exposed to very interesting documentaries and progressive films about the Cuban Revolution. Cuban cinema really shaped my approach to structure and storytelling. It also made me want to tell stories of sociopolitical and cultural relevance. Much later, before I left England in the mid-1970s, I saw The Other Francisco (1975) by Sergio Giral, a feature film set on a plantation in Cuba, which summed up all the ideas I have been dealing with in terms of form, content, and technique.

WAGNE: While screening You Hide Me at Kino Arsenal last summer, you mentioned that West Africa magazine, which was published in London between 1917 and 2004, discussed the film. It took a while for the film to become more popular. Nigeria was the first African country to actually buy a copy for its National Museum. When was that?

OWOO: In 1971. I made the film in 1970. A year later, I took it to Ghana, where it was banned. But the ban was publicized in the Daily Graphic, Ghana’s national newspaper: it ran a big editorial supporting the film, criticizing the ban. And West Africa magazine, which was based in London and I believe was owned by some Nigerian publishers with British sponsors, picked up the story. Back then, it was the only magazine that covered news, politics, and contemporary culture in West Africa. It was very popular and an essential source, if you wanted to know what was happening in Nigeria, Senegal, or along the West Coast of Africa. A lot of educational institutions, universities, and research institutions had a subscription. And for us, African students and Africans living in the UK, it became a way of catching up and keeping up with what was happening. And then when I got back to London from Ghana, where the film had been banned, the editor of the magazine got in touch with me, and I was able to screen You Hide Me at the Africa Center.

WAGNE: These days, you’re constantly receiving loan requests, especially from art museums in the Global North. Have you also been contacted by ethnological and/or anthropological museums – the very institutions that are most likely in possession of contested collections, looted African heritage? Are these institutions, which are quite central to the restitution debate, also looking for a dialog with you, or is it more art magazines?

OWOO: In fact, most major museums and institutions in Europe and North America have avoided me. The only organizations that have been in contact with me are cultural initiatives, sometimes universities and educational institutions or even NGOs. I’ve never been approached by any of these museums that are actually holding on to looted African artifacts.

Nii Kwate Owoo, “You Hide Me,” 1970

WAGNE: How are the discourses on colonial provenance research and around Africa’s material culture unfolding and being negotiated in Ghana – specifically in Accra, where you are based? What initiatives, projects, and approaches are there?

OWOO: The Ghana Ministry of Arts and Culture organized a conference I was invited to about two years ago, for example. A spectrum of academics and cultural activists met there to set up a campaign, a Ghanaian government-supported organization. This is important because the Ministry of Culture was the one that actually invited us to form a collective called the Focal Group, whose aim and objective it is to lay the foundation for the Ghanaian authorities to campaign for the return, restitution, and repatriation of our art objects in British and North American museums.

WAGNE: How do you assess and think about this three-year “loan” of the 32 artifacts, many of which were looted from the Asante Royal Court during the British War campaign against the Asante people in the 19th century? The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London are “lending” the artifacts back to Ghana, where they will be displayed in the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the seed of the Asante Kingdom …

OWOO: I’m in the process of making a documentary film about the return of these artifacts. I’ve started shooting the documentary. I was in Kumasi recently, in February, to witness the Fowler Museum’s items returning to the Manhyia Palace. I’m going back in a few weeks to document the temporary return of the Asante King’s artefacts, also known as Ghana’s “crown jewels.” I wasn’t part of the negotiations that decided on the items. But to me, it’s a journey. I see it as a journey of a thousand miles that begins in one step. I believe that it’s good that something is coming. Since the Sagrenti War over 150 years ago, I was the first person, through my film You Hide Me, to expose these looted items. Of course, I would prefer museums to return everything, but it’s not in my power to make them do so. What I’m doing is trying to produce a three-language version of You Hide Me, because in the Asante region the dominant language is Akan. I think of it as a way to decolonize the film, by translating it into local language. I’m almost done and will try to screen it in Kumasi before the arrival of the items from Britain, which has been scheduled for this month, but hasn’t yet happened.

WAGNE: And the new film you’re doing? What’s the title?

OWOO: The Asante Kingdom of Gold.

Nii Kwate Owoo, “The Asante Kingdom of Gold,” 2024 (Pre-production still)

WAGNE: I found this beautiful conversation between you and Ousmane Sembène, titled “The Language of Real Life.” To stick with the topic of language and your quest to decolonize You Hide Me by translating it into three local languages first and then produce further language versions, I wanted to end with this proverb that you recently shared with me: “a crab does not give birth to a bird.” Could you maybe just simply describe the meaning behind it and the role of language in your work?

OWOO: “A crab does not give birth to a bird” is an old proverb that originates from our traditional language. I use it to describe myself, because my father influenced my development as a political activist. He was a political activist before I was born. When I say a crab doesn’t give birth to a bird, it’s obvious: a crab will give birth to another crab. I grew up in the midst of my father’s political activity, in the struggle against British colonialism for the independence of Ghana. I’m a product of that era. And that era also influenced my take on language. When one nation conquests another, the conquerors impose their ideology and their language, their culture, and way of life onto the conquered nation. And because I grew up during the struggle for independence, which was against colonialism, when I became politically active, I began to realize that the importance of language was so critical. The three-language version of You Hide Me is my first production venture that puts this realization into practice, by decolonizing the English-language commentary into Ghanaian languages. I guess less than 1 percent of the Ghanaian population have seen the film or heard about it. The local-language versions will help reach local communities. There are several local-language television stations in Ghana now, from the south to the north, and they are searching for program ideas. My long-term goal is to do various language versions of You Hide Me, in Twi, Hausa, Ga, Ewe, for example. And after that, to move on to other languages in West Africa, like Yoruba, and perhaps even languages from Southern Africa and make the film available to people in different places, including rural areas.

WAGNE: Yes. I love that you’re willing to use the power of plurality and the power of language as a way to provide access. And it’s wonderful to see that there’s this major educational potential that You Hide Me provides, even 50 years after its release.

OWOO: I want my films to stimulate debate and discussions on a broader level. They shouldn’t become intellectual exercises accessible only to a small, privileged part of society, or the elite.

Nii Kwate Owoo was born and raised in Ghana and has been producing and directing films since the early seventies. After graduating from the London Film School, he formed the first Independent African film production company (Ifriqiyah Films) in the UK under which he produced and directed his first film You Hide Me. He worked as a research fellow and coordinator for the Film and Video department of Europe Africa Research Project in Gower Street London. In the late 70’s he organized the first African Peoples Festival of Films at the Keskidee Centre in Islington. Back in Ghana, he took up an appointment as a research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana and founded the Media Research Unit of the Institute in 1978. Nii Kwate Owoo has been active in the movement for a Pan African Cinema and has co-produced a series of documentaries. In 1991, he directed the feature documentary OUAGA - African Cinema Now (1988) with Dr. Kwesi Owusu as well as AMA, the first African feature film both financed by British Television network Channel Four. In 2002, his film Women of Substance, a feature documentary shot in six African countries for the African Women Development Fund (AWFD) received international acclaim. Nii Kwate Owoo is devoted to the research and exploration of the use of African cultural traditions and storytelling formats (orature) in film and video and to encourage cross media experimentation in the production process. His new five-part docudrama series The Asante Kingdom of Gold on the history of the Asante Empire is currently in the fund-raising stage.

Jeanne-Ange Wagne is an artistic-researcher, event curator and knowledge mediator, who engages in artistic research on (German) remembrance culture, colonial history and colonial provenance research. As a knowledge mediator, she regularly offers critical mediation formats for the public program of cultural and art institutions most recently for Villa Oppenheim, Brücke-Museum, Dekoloniale, and KW Institute for Contemporary Art. She has worked for the German branch of the transnational research project The Restitution of Knowledge, at the department of Art History at Technische Universität Berlin where in 2022 and 2023 she co-curated and coordinated the event series KuK-Tuesdays: Dislocation.

Image credit: Courtesy of Nii Kwate Owoo