RENÉ POLLESCH AND FABIAN HINRICHS, HANNE DARBOVEN AND ROSEMARIE TROCKEL, KÄTHE KOLLWITZ Seen & Read – by Isabelle Graw

Pollesch/Hinrichs, ja nichts ist ok

Pollesch/Hinrichs, “ja nichts ist ok,” Volksbühne, Berlin, 2024

Premiering just a few weeks prior to René Pollesch’s passing, this play was not typical for the dramatist on a textual level: his usually sharp, contradictory, and rapidly delivered reflections were replaced by what at times veered into a one-dimensional lament, enunciated slowly by Fabian Hinrichs, whose tone when declaring (for example) “I have no fear and no money” rendered the statement feeling a bit banal. The quarreling members of a shared apartment, on the other hand, are played rather affably by Hinrichs. To portray “Stefan,” he quickly puts on Stefan’s glasses; to embody “Claudia,” he throws on a pink piece of clothing. Striking here is how an emphatic belief in the collective – something originally central to Pollesch’s artistic direction at the Volksbühne – gives way to a realization of how difficult it is to live with others. To gain a little distance from one another, one member of the group even constructs a wall of DHL and Amazon packages through the middle of one of the apartment’s rooms. In the face of relentless conflict, the outspoken enthusiasm of the early days gives way to a disillusionment from which even Hinrichs’s escape to an Airbnb apartment with a micropool brings no relief: the old roommates manage to find their way into this new abode, too. Emotional distress, death, and suicide are leitmotifs throughout the play – Hinrichs’s desperate pleas for help sound out at the start of the piece, before he is forced to realize that the present conflicts have sapped all his joy. It would be short-sighted, however, to read the essentially melancholic tenor of ja, nichts ist ok (yes, nothing is ok) as Pollesch’s final legacy: this is far from the first of his plays to deal with death, and the piece was strongly shaped by Hinrichs’s input and performance.

Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, Berlin; upcoming performances on June 12, 23, and 26, 2024.

“Hanne Darboven and Rosemarie Trockel: Early Birds”

“Hanne Darboven und Rosemarie Trockel: Early Birds,” Galerie Crone, Berlin, 2024

In this exhibition, an encounter with the early drawings of Rosemarie Trockel and Hanne Darboven is compellingly staged as a dialog between two distinct artistic procedures. Darboven uses graph paper for her diagrammatic notations, while Trockel often employs long-since-yellowed sheets in book-page size to carry over a visual language that oscillates between figuration and abstraction. What unites both artists is their use of drawing as something of a diary – which is especially apparent in Trockel’s Tagebuch from 1984–85, a drawing that declares a Rorschach-like stain to be a diary entry. Darboven too opted for the daily routine of an “inscription system,” filling graph paper with calligraphic loops or cross-sum calculations. Her larger-scale projects, such as the Ein Jahrhundert (A Century) artist’s book, also provided the advantage of committing her to a daily ritual. Both artists use drawing less for experimentation and more as a practice for coping better with their own lived reality; likewise, the two of them often integrate words into their pieces, thereby transforming the works into linguistic propositions. Especially striking in Trockel’s oeuvre is how well the subtle humor of her 1980s drawings has aged: the 1986 ink drawing Ohne Titel (Untitled) is a fine example of this, with its Sisyphus-like figure attempting to climb up but always falling back down. The exhibition also strikes a successful note in terms of installation and framing, spatially juxtaposing the works in such a way that they explicitly enter into communication with one another. And the old-master-style frames that a number of Trockel’s drawings are enclosed in underscore the latter’s historical character, while also symbolizing their significance from a contemporary perspective.

Galerie Crone, Berlin, April 26–June 15, 2024.

“Kollwitz”

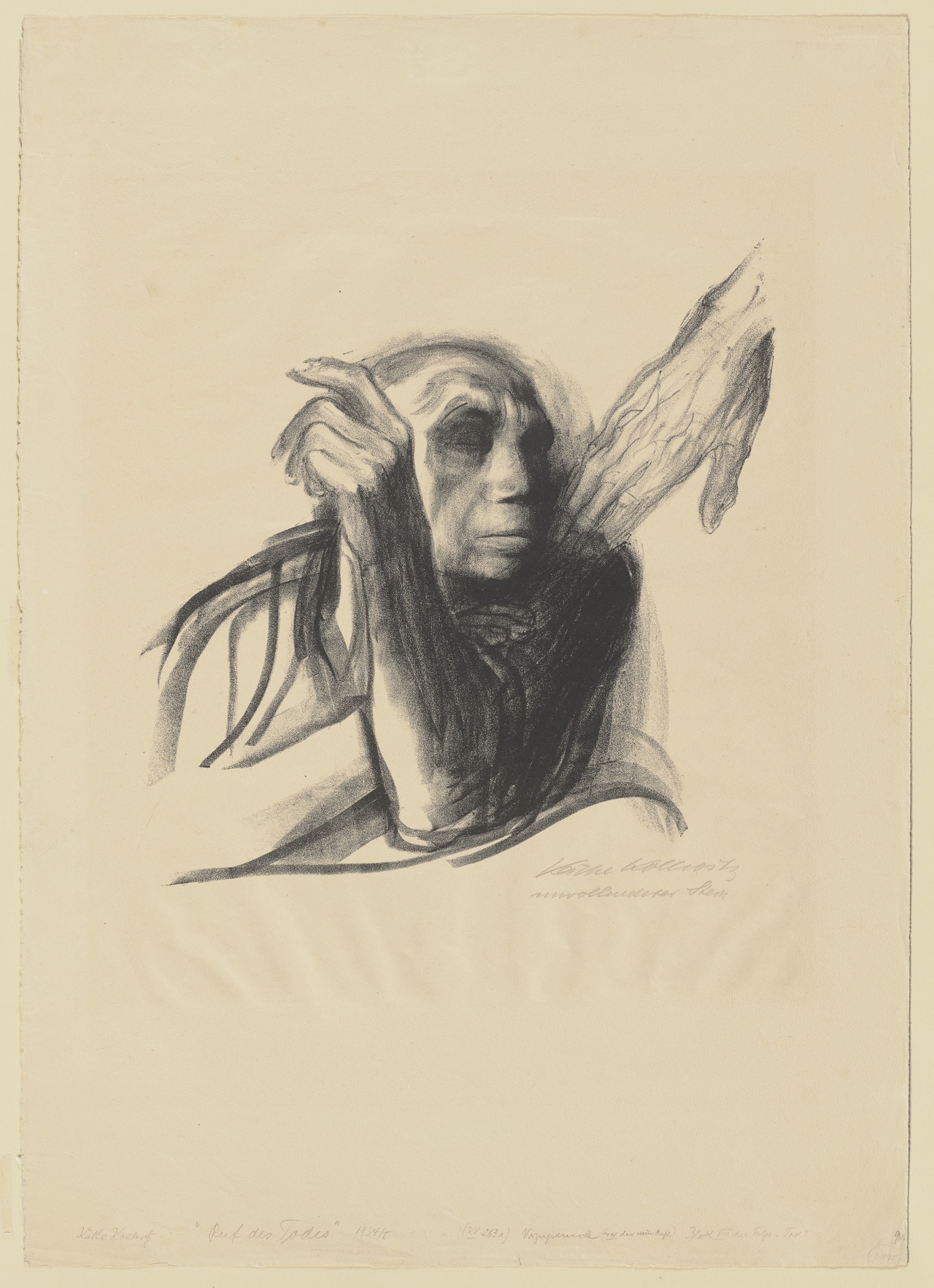

Käthe Kollwitz, “Ruf des Todes,” 1937

Why is there suddenly a Käthe Kollwitz revival? Especially at this point in time, given that since the 1970s the art world has seen her work largely as pathos-heavy agitprop? Beyond the exhibition at the Städel Museum bearing the unfortunate and sensationalist description The most famous woman artist in Germany, a showcase of her graphic works is currently running at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Numerous artists are making ever more frequent reference to Kollwitz as well, ranging from Sanya Kantarovsky’s quotations of her visual language in one of his paintings to Henry Taylor and Jill Mulleady’s integration of a Kollwitz drawing into their recent exhibition at the Schinkel Pavillon. To me, the current Kollwitz revival seems to be directly linked not only to current crises and wars but also to the resurgence of fascist tendencies. Indeed, Kollwitz used her overtly accessible visual language to fight against all such developments – in this context, one might think of her most famous graphic, Nie wieder Krieg (1924).

The exhibition at the Städel opens with a declaration that Kollwitz turned away from painting to solely dedicate herself to printmaking because of its political and communicative potential. A more thorough exploration of her departure from painting would have been beneficial though, especially considering that an oil self-portrait of hers demonstrates her undeniable skill in this area. One might speculate whether her turn to printmaking followed on from a realization that painting was mostly male territory at the time. Even in the first exhibition room, which is dedicated to Kollwitz’s self-portraits, her skillful use of pathos is evident. The emotions evoked in the titles – Klage (lament), for example – are illustrated with exaggerated gestures: here, a person clasping their hands intensely before their own face. In Ruf des Todes, Death reaches down toward the artist, who has depicted herself as an old woman recoiling violently from its grasp. Each gesture is marked by exaggeration; emotions are clearly defined and explicitly conveyed. Kollwitz’s radicality is especially evident in her numerous depictions of mothers who break from idealized notions of female parenthood: in Kollwitz’s work, we see them suffering from loneliness, sensing their status as a burden rather than a joy. What I found rather unnecessary, however, was the dedication of an entire room to her mentor Max Klinger, supposedly with the aim of highlighting differences between the two artists. Would the same treatment have been given to a male artist – a large section of his retrospective given over to a tribute to his teacher? Unlikely. The wall displaying Kollwitz’s political posters demonstrates how she so consistently found coherent and compelling visual formulas for conveying political messages. Here, however, there is no room for ambiguities, ambivalences, or openness to interpretation – the space for such nuances seems to vanish in face of the gravity of the situation.

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, March 20–June 9, 2024.

Isabelle Graw is the cofounder and publisher of TEXTE ZUR KUNST and teaches art history and theory at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste – Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. Her most recent publications include In Another World: Notes, 2014–2017 (Sternberg Press, 2020), Three Cases of Value Reflection: Ponge, Whitten, Banksy (Sternberg Press, 2021), and On the Benefits of Friendship (Sternberg Press, 2023).

Translation: Matthew James Scown

Image credit: 1. Photo Rob Kulisek; 2. © Thomas Aurin; 3. Courtesy Galerie Crone, photo Uwe Walter; 4. Photo Städel Museum