SEEN & READ – BY ISABELLE GRAW "La Naissance des Grands Magasins," Jörg Später, Ulrike Edschmid

“La naissance des grands magasins: 1852–1925”

“Les Grands Magasins Dufayel,” 1895–1900

The triumphant rise of Paris’s department stores required certain socioeconomic conditions, as this exhibition vividly demonstrates. A first decisive factor was the formation of a new social class toward the end of the 19th century – the bourgeoisie – whose then-burgeoning sense of self-confidence can be seen in a series of commissioned portraits that opens the exhibition. Here, self-assured businessmen pose alongside their elegantly dressed wives. The department stores also benefited from the so-called Haussmannization of Paris, which famously saw swathes of the city demolished and replaced with grand boulevards: these wide streets were perfect for leisurely strolling, which made them a location of choice for department stores. Graphic materials demonstrate the enormously significant role played by the expansion of the rail network, which made transporting goods easier and allowed those living outside the capital to easily visit it to go shopping or have goods delivered to them at home. The exhibition also emphasizes how department stores benefited from the ongoing industrialization of France, the products of which were celebrated in the Expositions Universelles. Beyond this, the emergence of leisure pursuits such as attending balls, visiting the theater, and walking for pleasure all fueled the rise of Paris’s department stores, since each of these activities required a suitable outfit. Looking at the posters and catalogues on display, it’s striking how little the marketing strategies of around 1900 differ from those of today, even if their specific visual and textual strategies are typical of the era. Already then, there were seasonal “clearance sales,” monthly promotions, home deliveries, and collaborations with famous designers – like Maurice Dufrêne, who designed a range of furniture for Galeries Lafayette. Early department stores attracted people from different social classes, since they gave visitors an opportunity to stroll through opulent surroundings for free; the fact that they could amuse themselves without having to pay for entry was a novelty, as the exhibition rightly underlines. That the majority of visitors to department stores such as Le Bon Marché are now well-heeled Parisians and wealthy tourists seems to be due to invisible barriers, however: whereas 19th-century shoppers could rummage through bins of goods in search of a bargain, most departments stores of today resemble art fairs, with curated booths featuring individual brands. The democratic promise of the department store has long disappeared, then. No longer a “ladies’ paradise” (Émile Zola), it now tends to be a high-end destination meant primarily for the rich.

Musée des Art décoratifs, Paris, April 10–October 13, 2024.

Jörg Später, Adornos Erben

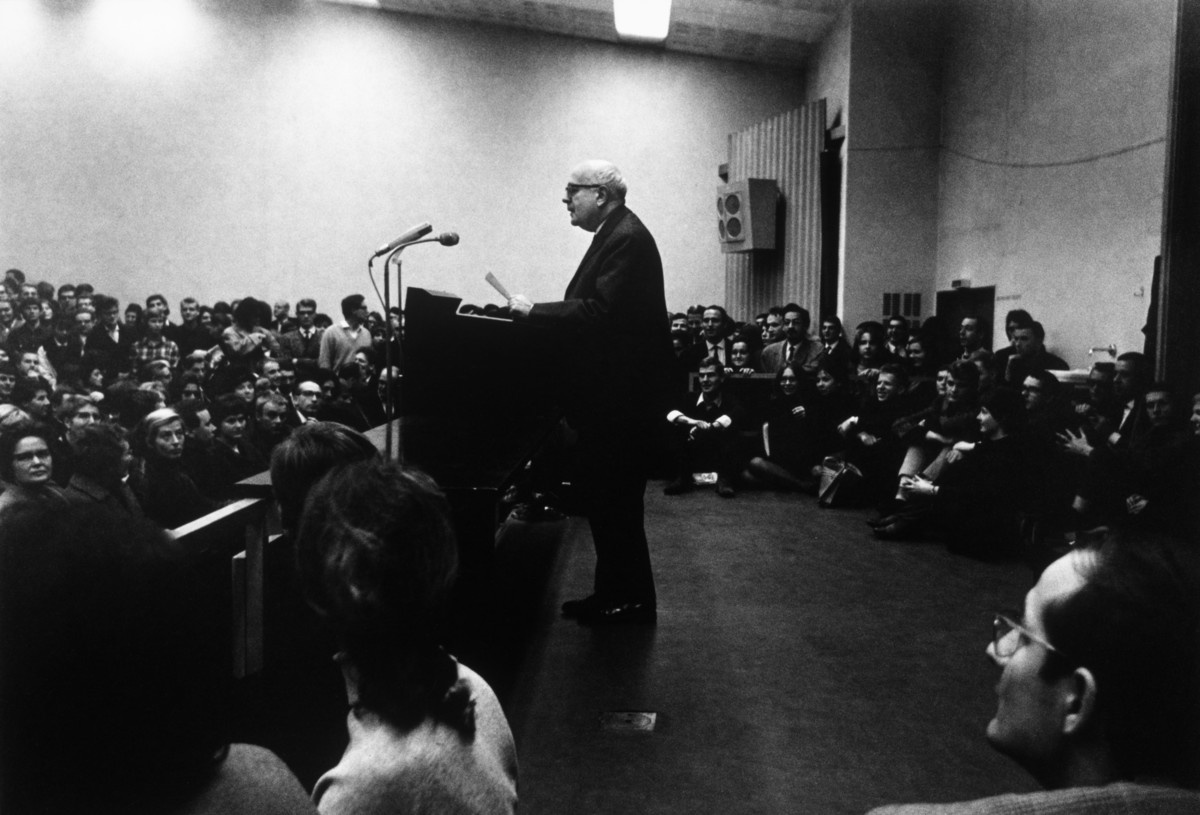

Theodor W. Adorno at the University of Frankfurt, 1964

Jörg Später’s new book on “Adorno’s heirs” is a grippingly written “narrative history of theory,” offering new historical perspectives and theoretical insights even for those well-versed in critical theory. His focus is not just on the first generation of Theodor W. Adorno’s students, but also on the battles and front lines of the culture wars around intellectual history within West Germany – from the student movement of the 1960s to the Historikerstreit of the 1980s, when the question of how Germany should deal with its legacy of Nazism and the Holocaust became a matter of public debate. For example, Später reminds us that even after 1945, “Nazis, opportunists, and conservative revolutionaries” occupied many of the leading positions within the German media, literary world, and universities. To talk of left-wing cultural hegemony in the 1970s is thus a misnomer, he claims – only a few universities actually gave positions to critical theorists, as in Bremen and Hannover. Später’s study also stands out for its special focus on Adorno’s female students, such as Helge Pross and Elisabeth Lenk. Their work – on the significance of gender in education (Pross), for example, or on André Breton’s poetic materialism (Lenk) – receives close attention and recognition from Später here, and I immediately ordered their books myself. He also demonstrates how the Habermasian shift from a philosophy of the subject to communication theory weakened (and ultimately depoliticized) critical theory. According to Später, the 1968 generation’s fascination with Adorno was not only due to the latter’s irresistibly apodictic way of speaking, but also to the student movement’s “negative identification with the persecuted.” The fact that Adorno rejected the students’ political engagement – preferring to write rather than sign open letters, and to play the piano rather than protest – contributed significantly to his rift with the movement. As Später demonstrates, the anti-authoritarian milieu of the time was fairly hostile to theory, more interested in self-organization than abstract ideas. This politicization also had its price, then.

Später also addresses the anti-imperialist left’s battle against Israel – including its afterlife in the current conflict. In Später’s view, this battle began following the Six-Day War of 1967, which he sees as having partly served to “iron out” German guilt: by insinuating the victims of the Nazi regime were capable of the same barbarities once inflicted on them, he claims, some Germans were able to relieve their own guilt about the Holocaust. From that point on, many leftists saw Israel purely as a “Zionist colonial state,” with some going on to draw “unacceptable parallels between Israel’s military conduct and the crimes of the Nazis” during the Israel-Lebanon war of 1982. On this point, Später invokes Detlev Claussen’s claim that, by the mid-1970s, the idea of “never again” was as good as forgotten, despite the pivotal role it had played in forging a leftist consciousness in Germany after the war. It can be argued here that there were other reasons to become left-wing, such as the fight against inequality or the belief in a better alternative to the capitalist system. Some of Später’s remarks on the “leftist scene” display a slight tendency for totalization. For it’s clearly not the case that all leftists – “whether anti-imperialist, anti-German, or post-colonial” – are “trapped in the Israel complex” to this day, even if he rightly goes on to ground this complex in German guilt. There are also more nuanced propositions on this subject, however, such as the distinction Später draws (following Dan Diner) between “historical Zionism,” whose cause he sees as having been justified by the crimes of the Nazis, and the Zionist social structure of Israel as a country, which can be justly criticized. Finally, he makes a convincing argument that the Historikerstreit – that is, the dispute triggered by Ernst Nolte’s assertion that there is a “causal nexus” between the gulag and the Holocaust – not only shifted blame for the Holocaust away from Germans but also came close to arguments made by the Nazis themselves. In Später’s historical perspective, however, the Historikerstreit also triggered urgent and long-overdue “criminological research into the mass murders and crimes [of the Nazis], above all in eastern Europe.” While Nolte sought to draw a line under the Holocaust, then, the result was actually the opposite. Two touring exhibitions on the subject were produced by the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, for example, prompting much discussion and raising awareness of the crimes committed by the Wehrmacht especially. As Später appositely writes: “The past that refused to disappear after Nolte’s lament now began in earnest.”

Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2024.

Ulrike Edschmid, Die letzte Patientin

Ulrike Edschmid

I consider Ulrike Edschmid to be one of the most important authors working in German today. She manages to combine the individual biographies of her mostly female protagonists with the social conditions they live under, and her use of language is compelling – her only equal here is Annie Ernaux. Her newest book is a good example of this. Die letzte Patientin (The Last Patient) tells the story of the author’s former flatmate, who dropped out of society in the 1970s as a young woman and, after a long odyssey spent unsuccessfully looking for love, eventually trained to be a therapist. Edschmid’s account of her friend’s peripatetic life between Barcelona and Latin America – chosen home to many in leftist milieus at that time – seems both dry and full of empathy. You’re reminded on every page how typical this biography was back then, when breaking with bourgeois norms was common among leftists and dropping out carried far fewer risks (both economic and social) than it does today. The author claims the story is based on letters from the friend – a literary trick that ensures a trace of authenticity runs through the fictionalized life story. The power and gender relations of the era also resonate through all the terrible things her friend experiences on her travels. Young women who wanted to escape their bourgeois backgrounds faced particular obstacles back then (as they still do); any young woman who traveled and hitchhiked alone faced being raped, for example, which in the case of the author’s friend happens twice. The more passionately she plunges herself into her endless love affairs, the faster the men are to distance themselves from her. She also has to learn that the pain inflicted by one’s parents can catch up with you even when you’re on another continent. Her perspective on her personal dramas seems astoundingly self-reflective and clear-headed: she knows her demons well, and yet she still repeatedly falls into the abyss of her own unsatisfied desires. She travels across world, stumbling from one unhappy love affair to the next and making repeated attempts at a fresh start with a new partner, only to pack up and move on again a short time later. At some point she notices a lump in her breast, receives treatment, and begins training to become a therapist. Using the small inheritance she received from her parents, she buys a house outside Barcelona and sets up practice there. It’s here that the eponymous “last patient” makes her appearance: an equally traumatized woman named “N,” who sits across from her therapist for years without saying a word. The silent suffering of this woman acts like a mirror for the protagonist’s own trauma, and she repeatedly tries to break off the therapy and send her client to a colleague. It’s all no avail, however: her silent patient will be with her until the end. While the men in her life were a disappointment, she can always rely on her women friends. With this book, one of these friends has paid her a literary tribute and (indirectly) given her a voice.

Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2024.

Image credit: 1. © Rob Kulisek; 2. © Les Arts Décoratifs; 3. photo Abisag Tüllmann, public domain; 4. © Lukas Hemleb / Suhrkamp Verlag