A POLY-LOG ON “DOCUMENTA FIFTEEN” Hosted by Raqs Media Collective, with Ivana Franke, Lantian Xie, Michelle Wong, and Merv Espina

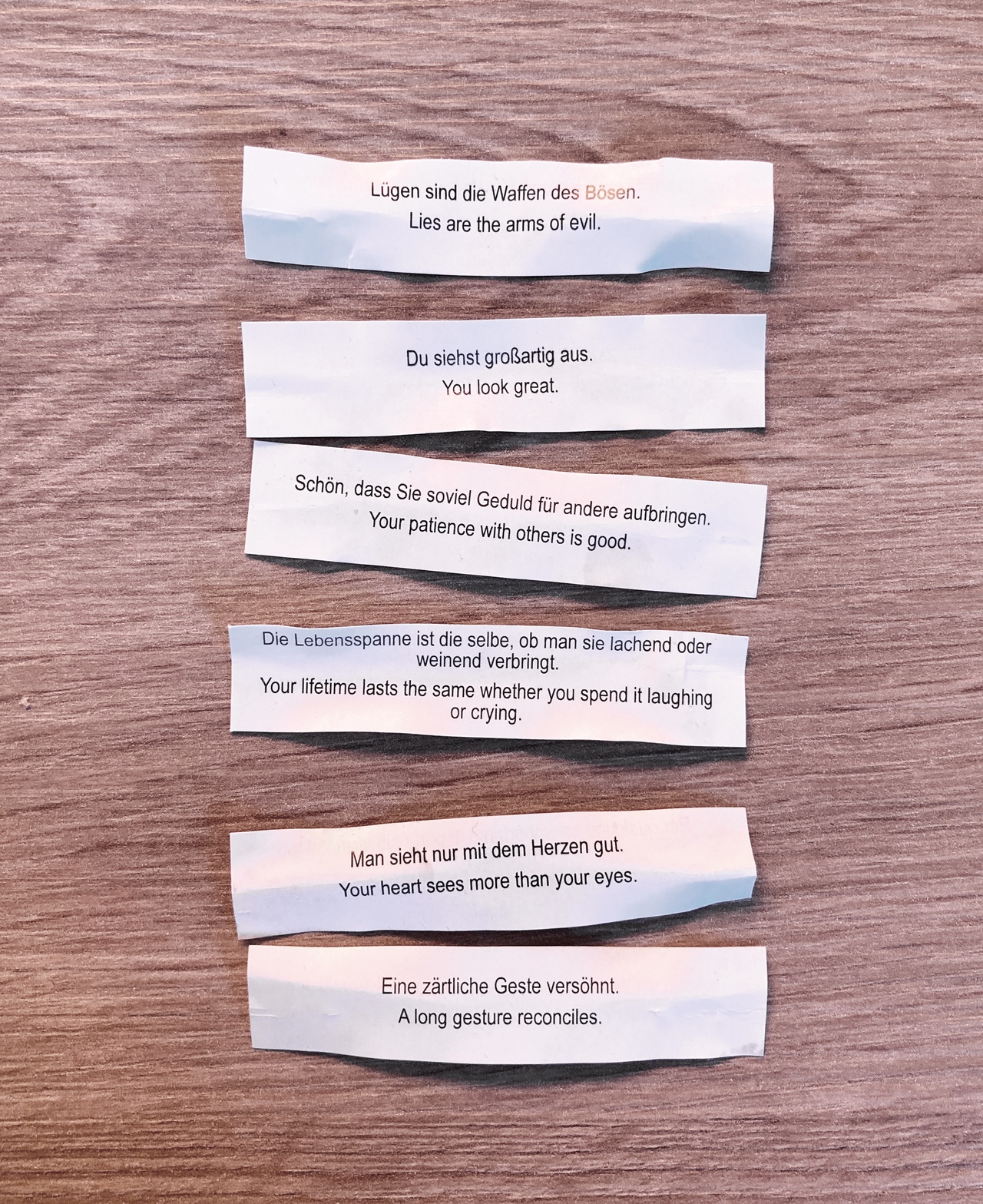

Fortune cookie poem composed during “documenta fifteen”

Monica Narula (MN/Raqs): This is now that moment in Europe when various kinds of institutions are having a moment of self-reflection on what went down at “documenta fifteen.” I’ve been having conversations with people here in Paris. Many want to support this iteration but are not entirely sure why their experience of the show was not as historically textured as they might have wanted it to be. My experience of “documenta fifteen” was mediated by Merv and Michelle, who already had a deep sense of affection for it. They generously gave us a tour of the exhibition, with open arms: engaging with what the stakes were, what kind of conversations were happening, the everyday texture of things, and this made our experience expansive. I came out of it moved; I had not gone into it thinking that would be the outcome.

Lantian Xie (LX): The sense I am getting from what Monica is saying is a kind of choreography through the space.

Merv Espina (ME): On our walk, we started with sites that aren’t usually visited because people maybe would start from the center. So, we departed from the usual. The day started from the periphery. We started from the outside, then worked our way in, ending at the Fridericianum. Our walk started with the artists of contention; we wanted to take you there first. Because there was always this danger of them potentially taking down more of the works as time went on, as they were constantly being, I guess, challenged, harassed. The Fridericianum, the center, also had Gudkitchen, a place to unwind, so we wanted to end there.

Nordstadtpark, Kassel

Jeebesh Bagchi (JB/Raqs): “documenta11” in 2002 was an invitation to a rupture in the art historical framework. It really affected how any art historical event would, from then on, articulate itself. Artworks were axial, weaving in multiple genealogies, geographies, and histories. Okwui’s platforms were crucial moments too, and all this changed directions of the art world. “documenta 14” in 2017 had invited an unpacking of modernist forms through diverse practices of storytelling, drawing from many sites outside Europe and sidestepping part of Europe as well. With “documenta fifteen,” the conversation is not about works – that is to say, works don’t determine the trajectory of thinking. We encountered a different imagination of the body of the artist, displacing a meritocratic framework, which is so prevalent in the world today. It not only displaces the figure of the artist but the range of assumptions around entitlement as well. Michelle captured this eloquently when she said that she felt a “suspension” that was generative. The question is: How was this achieved?

Ivana Franke (IF): When you come to an exhibition, you have expectations that define how you engage with the exhibition and the artworks. This has to do with what is familiar, in terms of the modes that give value to what you can recognize within the artwork. At “documenta fifteen,” art historical references didn’t order this engagement; rather, artworks were exhibited in a kind of accessible, friendly way. This didn’t allow for the habitual relay into the whole institutional system and the art market. Well, then many in the field felt excluded! Art historians were not actually establishing the value system here anymore. This collapse of accepted relational modes brings into question the very foundations of what is considered an art-world framework. “documenta fifteen” changed the context completely. A new situation was created to engage with works, together with other people, making it a kind of communal experience.

JB: This communal experience: How is it achieved? “documenta fifteen” carried a sense of existing in a different way. Some people argued that it was more enjoyable for the participants and not so great for the onlookers. An exhibition for participants versus an exhibition for onlookers – a gap that can leave the latter a bit befuddled and bewildered. But this feeling – that it is a communal experience, a shared experience, not an isolated experience of your own – bridged that gap between onlooker and participant.

IF: The methodology used to achieve that communal experience didn’t feel so curatorial; it was more about infrastructure.

Michelle Wong (MW): I think some rules or protocols were suspended – but not all: I think charging for a ticket sort of precludes a certain kind of participation, or even onlooking from people who are there already. Ivana points to a different way of framing. Through the event, old frameworks were suspended, and we therefore had to suspend our own expectations as to what the definition of an artist is, and as to what an art object is. Jeebesh spoke about the onlooking and participating. Maybe this was one of the most significant suspensions. Who tells you to be an onlooker or a participant? And what about when I am not a participant but decide to behave like one? A specific mode of being part of an audience is possible because you know the protocol already, but here it was very different from that usual protocol. It made certain people uncomfortable: there was the sense that they wanted to participate but didn’t know enough to do so. We all seemed to share this domain of experience during our time at Documenta, but what is it? What kind of beauty or confidence is this?

Gudskul’s “Gudkitchen”

MN: That’s where the protocol of hospitality comes in. As Michelle is framing it, this is what you would think is not necessarily defined by the idea of an art experience but by the protocol. Picking up on what Ivana was saying, a certain order of experience, a certain register of engagement, had opened up from the beginning. And perhaps hospitality plays a role in this. What I’m going to say may sound divisive, but when people from other parts of the world arrive to work in European institutions, they find themselves asking: Why is there no culture of hospitality here? This is one way of expressing that what is important is an order of experience, rather than an order of engagement. What is important is the quality of the experience, rather than just the protocols of engagement.

LX: I think the guest brings the hospitality, no? I mean, the guest renders a certain kind of environment. If that guest is not there, then it’s just a budget category on a spreadsheet. These capacities, like infrastructure, make sense only through the appearance of this person – the guest. Ivana brought up infrastructure versus curating. Raqs has worked with the formulation of the protagonist, and it’s worth bringing it into the onlooker-versus-participant discussions, as it denotes a role that transcends this binary threshold. I’m drawing on some larger formulation of the hospitality of the guest embodied in the itinerary that Merv and Michelle put together. I received it thirdhand. And I felt a compression or condensation because of starting from the periphery. And it got more condensed as I reached the Fridericianum – a multi-surface with altered haptics, and a phenomenon which was a threshold mediation on both securitization and sanitation. You were invited to lie down on, sit down on, lean against all kinds of things – a choreography for the body. The emphasis on direct transfer mechanics made things palpable. It kept the experience hand-sized; there was a kind of ergonomics around it, like a collage. On the ground floor, there was a four-player chess game. I sat down with three people from Germany. One was a young person who had visited many times and played the game, acting as a kind of impromptu facilitator, traversing the onlooker threshold. And two others wanted to dip their toes into the game, to test it out a little, but maybe the metaphorical water was a bit cold. The facilitator, however, brought them to the water’s edge and the conversation thus switched from an adversarial into an admissible logic of the optimization of cooperation.

IF: Hospitality may be the main factor because the sanitation of the art historical methodologies was replaced by hospitality, and care was thereby brought into art historical discourse. This feeling of being welcome was a huge change. For example, my brother, a scientist, visited with his friends and thought it to be the most inclusive, amazing exhibition that he had ever seen – and he visits a lot of exhibitions. The sense of hospitality was embedded in the exhibition’s infrastructure. You kept seeing this sign “Make Friends, Not Art.” However, for some, this hospitality can also be experienced as a threat, an intrusion from far away.

ME: Not a lot of people realize that this Documenta had a lot of consideration for the dramaturgy. It started as a series of invitations which extended into an invitation chain not only to other artists but also to certain populations. In Kassel, there’s a Vietnamese community which has never really felt invited before but now entered and expanded their presence because of some of the artists. So, the invitations unleashed a chain reaction. These sequences of invitations and certain knowledges, such as where and when you could get a free Documenta mug, were not about creating secret systems, or secret knowledge. It was a system that ruangrupa put in place to disseminate information. It was all part of the dramaturgy they constructed. And it’s not so different from how I have felt when working with ruangrupa in, say, the Jakarta Biennale 2015. I’ve felt at ease and amongst friends, even though it might at some moments feel like chaos.

JB: This exhibition has been talked of as a kind of visitation from the South. This kind of decentered life, combined with hospitality and friendliness, is common in Jakarta, São Paulo, or Lagos. It’s part of the fabrication of a substrate of life which has not yet been fully pulled into the pure transaction of monetized time. Depending on from where this is seen, this may be a threat, or sometimes a love affair. Documenta is an exhibition that reviews the art world every five years. It reveals what exactly is at stake in the art world. What if the substrate truly becomes infrastructure or a dramaturgy, and then transforms into procedure? From a dispositional question within cultures this is now a procedural question. Even if such a shift doesn’t change institutions, it definitely pushes them to anticipate subspaces and alternate flows.

Jatiwangi art Factory (JaF) at Fridericianum

MW: Every time that you try to put a protocol on it, or you try to tell it how to behave, it will find a way to then undiscipline itself. And I think that, for some, is very unsettling. Monica was raising something a while ago: What kind of experience do you want your friends to have? You want them to have fun, you want them to be warm, you want them to be fed. You want them not to be in pain. So, I think these are some of the things that we were definitely thinking about when we were choreographing the walk for Monica and Jeebesh through “documenta fifteen.” There were lots of people from Hong Kong who stayed at Documenta later in July and August. I heard from them how it’s a constant struggle, or a tug of war of celebration of what this is doing, what this can do. There are also some critical voices that say this is not the first Documenta that has tried to break some protocols and tried to do things differently…

JB: Mirwan Andan (from ruangrupa) started a WhatsApp group in late 2020 called “re-reading.” He was all into re-, as in reframe, reread, reillustrate. And when “documenta fifteen” happened, it all became un-, as in unpack, unsettle, unravel. Re- was gone and un- took over.

IF: That said, undisciplined, the term Michelle was using, sounds very precise.

MN: To be undisciplined in an exhibition is challenging to all those present.

IF: Because it’s about breaking all the rules. Actually, it’s also excluding people – those who fully rely on (or can’t do without) the rules.

ME: “documenta fifteen” was a launchpad for the larger lumbung project. There is a practice used in the Philippines, called paluwagan, where it’s a communal pool of funds, right? It’s a communal pot.

MN: In many parts of the world, when something is not available, you find modalities around it in order to thrive. We all have histories of doing that. The infrastructural question is truly infrastructural in certain situations, such as the artistic context in Indonesia, but when it is brought into play in another context, it shifts from being infrastructural to being curatorial. Ivana was making a distinction between infrastructure and curation. And I’m just wondering if one can even establish such a separation. What does this distinction mean in contexts where it is the disposition of living? To me a mix of the dispositional and the situating of systems as infrastructural situations moves everything into the methodological question – How does one make things happen? – and this is also a curatorial question. This shift, in many ways, will affect ways of doing exhibitions and of running institutions, too. And what are the ripples if not global ripples?

MW: This reminds me of a friend we met on the train. Maybe Merv should tell that story.

ME: We met an artist from Israel on the train. He lives in Frankfurt. We were on a train going to Berlin. He was curious about Documenta and had loved the human aspects of it, how different people from various backgrounds with varied practices were coming together. He did not discuss what was considered the most obvious to some people and what was in the press. Which we found refreshing.

MW: And we ended up talking with and about him. He has been in Germany for 20 to 25 years. I think our encounter and conversation with him is a very interesting story that emerged from what, at least I assumed, might be a very contentious and heated encounter, given we were just coming from Kassel. But that assumption of how our exchange would unfold became suspended, and it became something else instead. I find that incredibly moving. In Berlin, he came to other events such as screenings that Merv was holding just to see and support them, and that sort of continues to roll and be generative. He still writes to us sometimes.

Unknown: We are all guests. [1] Think about it. Every one of us, after we understand our planetary connections, is a guest. The impending catastrophic or impending survival story. The planet has appeared. Nobody really can be only a host, as you are also a guest in something that is impermanent, fragile, unstable, and you have to give up being divided by the idea of narrow homes.

Unknown: So, you can only be a guest.

Unknown: That’s the proposition. Yes. That’s nice. I like this vaporization of the host.

Recording of an online meeting held on October 2022, transcribed by Oorja Garg at the Raqs Studio, Delhi.

Michelle Wun Ting Wong is a researcher based in Hong Kong.

Lantian Xie makes images, objects, concepts, motorcycles, and parties. Previous exhibitions include 57th Venice Biennial, 11th Shanghai Biennial, 3rd Kochi-Muziris Biennial, 14th Sharjah Biennial, 7th Yokohama Triennale.

Merv Espina is an artist and researcher based in Las Piñas. His work investigates the fissures of systemic biases and historical lapses in media, knowledge and cultural production, and the networks and organisms that have grown through them.

Ivana Franke is a visual artist. Devised to challenge our habitual cognitive and behavioural patterns, her investigations of light, space and perceptual psychology take forms of immersive installations, sculptures and drawings appearing within the range of our perceptual thresholds. In 2022, her solo exhibition “Twilight: Neither perception nor non-perception” was presented in Kunsthalle Berne, and a recent public installation was “Resonance of the Unforeseen” stretched over the long front of the Yokohama Museum of Art in 2020, as a part of Afterglow, Yokohama Triennale. With her solo show “Latency” she represented Croatia at the Venice Biennale in 2007. She lives and works in Berlin.

Raqs Media Collective was formed in 1992 in Delhi, India by Monica Narula, Jeebesh Bagchi and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. The word “raqs” in several languages denotes an intensification of awareness and presence attained by whirling, turning, being in a state of revolution. Raqs take this sense to mean ‘kinetic contemplation’ and a restless entanglement with the world, and with time. The members of Raqs live and work in Delhi, India. In 2001, they co-founded the Sarai program at CSDS New Delhi and ran it for a decade, where they edited the 9 volume Sarai Reader series. Recent exhibitions include “The Laughter of Tears” (2021, Kunstverein Braunschweig) and “Hungry for Time: an invitation to epistemic disobedience with Raqs Media Collective” (2021, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna).

Image credits: 1. Courtesy of Michelle Wong; 2 - 3. Courtesy of “documenta fifteen”, photos Nicolas Wefers; 4. Courtesy of “documenta fifteen”, photo Martha Friedel

Notes

| [1] | The unknown as a speaker lends their voice to all participants in this conversation and beyond. |