KILLING YOU SOFTLY Annette Weisser on “Diego Garcia“ by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams

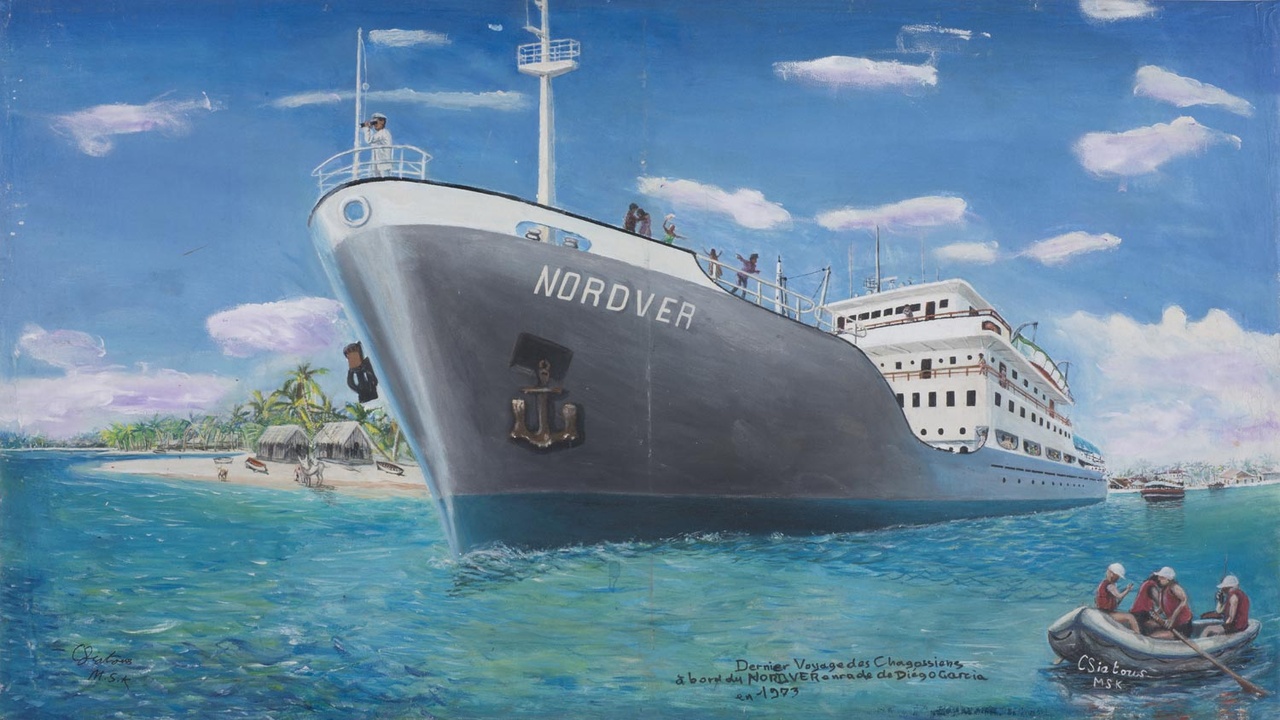

Clement Siatous, “Dernier Voyage des Chagossiens a bord du Nordvar anrade Diego Garcia, en 1973 / The Last Voyage of Chagossians on board The Nordvar from Diego Garcia, in 1973,” 2006

Diego Garcia, by Natasha Soobramanien and Luke Williams, is not an easy book to read: I want to use the German word sperrig to describe it — the book resists literary classification, and in this it’s part of an ongoing shattering of the novelistic form. But once the reader accepts this assemblage of differing textual modes as a novel, it opens up like the world: fragmented and shattered itself, beyond coherent narration. Soobramanien and Williams have both published novels individually, and Diego Garcia is the fruit of their friendship and shared concerns – namely, the deadly effect of individuation (the book was partly written during the pandemic) and adequate ways of tackling contemporary reality in writing: “We think of it as a novel for the age of the internet,” as Williams described it to me in a recent Zoom conversation. And, in fact, Diego Garcia is intensely googleable: names, places, historical facts as well as historical fictions and the facts these fictions produced over time. Wikipedia entries made their way into the book alongside quotes from other writers and film scripts. Both writers studied with W. G. Sebald, and Diego Garcia echoes Sebald’s destabilizing engagement with history, as well as the deep melancholy that pervades Sebald’s writing.

Several chapters of the book had been published beforehand on different platforms, and Soobramanien and Williams – who live in Brussels and Cove, on the west coast of Scotland, respectively – had convened for short periods of time to write together. In between, they wrote emails, sent letters, took notes, made lists. Some of this peripheral text production entered the book. There are two perfunctory characters: Damaris Caleemootoo and Oliver Pablo Herzberg. At no point do we get a sense of how Damaris and Oliver look; we do, however, get very precise accounts of what they read, and what they underline in their readings, down to the page number. This strikes me as oddly medium-specific: Why bother creating the visual impression of a person in a text-based medium? What a waste of time! This exasperation with traditional ways of describing characters is sort of an in-joke in most autofiction from recent years. The effect is ambivalent: as a reader from more or less the same sociocultural habitat (the academically inclined branch of the international art world), I feel as if I already know these people: they’re friends of friends. I would, however, hesitate to recommend this novel to anyone from outside this particular sphere. If the names Fred Moten, Kader Attia, or Wu Tsang mean nothing to you, you might find it quite hermetic.

Diego Garcia is very much a book about writing: Damaris and Oliver both struggle with their respective literary projects. They share a flat in Edinburgh, and there’s a Groundhog Day theme of them trying to get to the National Library every morning in order to work. Every morning, something stops them. They get stuck in their favorite Swedish café, or the local charity shop, or it starts to rain. They bicker, they fight, they anxiously watch their small Bitcoin fortune shrink. (The money is, or was, an advance Oliver had received from his publisher after his successful debut novel.) They smoke, they drink coffee, and, from early evening on, beer. They discuss who should pay the bills. Economy is important, as it shapes reality like nothing else. At one point, after a long walk up to Arthur’s Seat, they separate, and the page splits in two vertical columns to record their parallel existence until they reunite. This portrait of an intimate friendship that isn’t a love story but a shared sensibility – a way of being in the world and toward it – is in itself rare and beautiful.

The real reason Damaris and Oliver are stuck is the recent suicide of Daniel, Oliver’s brother and Damaris’s close friend. Daniel, an art student at Goldsmiths, simply couldn’t take it any longer. Their mourning is not connected but rather experienced in proximity to a research project they embark upon after getting distracted one morning on their way to the library when they meet a poet named Diego.

Diego is named after the homeland of his mother: Diego Garcia, an island of the Chagos Archipelago. It was home to the Chagossians who had been expelled with brutal force between 1968 and 1973 when the UK government made a shady deal with the US government to establish a military base on the island. At a time when colonial rule officially came to an end, the foundation of the British Indian Ocean Territory – to which Diego Garcia belongs – effectively extends colonialism into the present. The central fiction around which this legal construct is built is that the island was never home to a people, but rather a fleeting population of workers descendant from slaves. The Chagossians, today dispersed around the globe from Mauritius to the UK, think otherwise: since 2006 they have been fighting for their recognition as a people and their return to Diego Garcia, which has been met with increasing success. (Look it up, it’s all on Wikipedia!)

Like other displaced people, the Chagossians suffer from a higher rate of suicide, alcoholism, and mental illness compared to the population of their host countries. In Chagossian Creole, their malady is called sagren, from the French word for sadness, chagrin. But unlike sadness, sagren is experienced collectively. It’s a shared and prolonged state of mourning for what they have lost: their way of life, their language, and their culture. But sagren also becomes the force behind their resistance. These two modes of mourning – Damaris’s and Oliver’s mourning for Daniel, the Chagossians’ mourning for their lost paradise – share the space of the novel. Together, they form a third kind of mourning: the mourning for a loss of collectivity, of forms of attachment, in our hyper-individuated societies.

A quote by Moten opens the book: “The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?”

No reasons are given for Daniel’s suicide. Damaris and Oliver refer frequently to the last piece he worked on, a video of him dancing (not in a happy way, they point out to each other) that begins with a quote by James Baldwin.

“How to share a story that is not yours to tell?” is a question posed on the book jacket of the US edition of Diego Garcia (Semiotext(e), 2022). Perhaps Daniel’s art, as well as this novel, could be considered an experiment in writing in solidarity with people whom “this shit” had killed harder, and faster. While obsessively researching the history of Diego Garcia, Damaris and Oliver register how political and economic violence penetrates their own existence as freelance writers in northern Europe. Soobramanien and Williams don’t claim the struggle of the Chagossian people; they recognize their entanglement in the same web.

I read Diego Garcia as a manual to navigate the present: pull any thread and follow where it takes you. Use your higher education to understand abstractions: cryptocurrency, legal fictions, national debt. Mistrust love, trust friendship. Exercise solidarity like a muscle. Come out collectively on the other side of sadness.

Annette Weisser ist Künstlerin and Autorin und lebt in Berlin. Sie ist seit 2020 Professorin an der Kunsthochschule Kassel.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Clement Siatous