MOURNING BEYOND MELANCHOLIA Jamieson Webster on "Blown Away: Refinding Life After My Son’s Suicide" by Richard Boothby

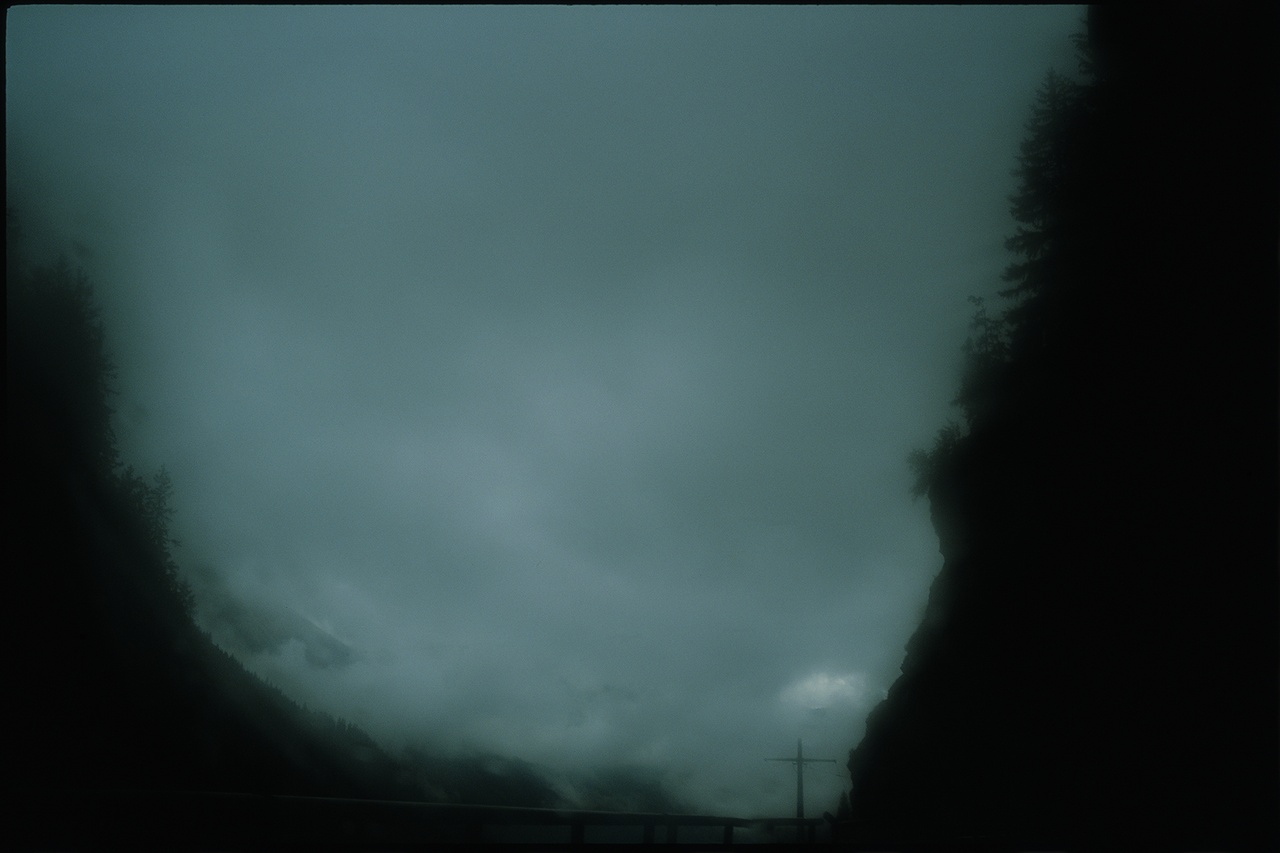

Nan Goldin, "Cross in the Fog, Brides-les-bains," 2002

While the opioid epidemic consists of accidental overdoses, what if it is also a melancholic act? Over 92,000 people died from opioid overdoses in the United States in 2020, an increase of 31 percent from the year before. What lack of mourning on a societal scale has helped create such a catastrophe? What do we need to hear in these deaths? I would add to this the bewildering 60 percent increase in suicides among teenagers, now the second-leading cause of death for that vulnerable age group. Suicide by suffocation is the method du jour for reasons unknown but can account for a large part of the increased percentage because of its lethality. Opioid death is also a stoppage of breath.

Freud famously said about melancholia that it is the problem of being crushed by an object that is lost. He surmised that this often happens when the work of mourning cannot begin because we do not really understand what we have lost. We don’t know where or how to account for the feelings of loss; perhaps we don’t even know what the loss has to do with us or how to place this loss in the story of our lives. We become lost in loss. Could this be the feeling of asphyxiation?

I want to turn to something local, intimate, specific. In Blown Away: Refinding Life After My Son’s Suicide, the recent memoir by philosopher and psychoanalytic theorist Richard Boothby, the author recounts reckoning with his son’s suicide by gunshot after struggling for years with addiction. It’s not the suicide that I want to speak about, although the title of the memoir is breathtaking and painful in its precision; the book offers a rare description of the way mourning a suicide is worked through in psychoanalysis.

Boothby describes the moment he emerges from two years of painful mourning: one year, as he put it, of shock, endless crying, and pure pain, and then a second year, somehow numb and wrecked, which was an even worse state. Pursuing the guilt with which he lacerated himself in session after session with his psychoanalyst, he finally acknowledged his own disavowed violence, something he came to through a forgotten memory from childhood of participating in the act of killing a helpless turtle. This somehow allowed him to emerge from the endless state of numb pain. The truth about himself that he had misrecognized didn’t explain his son’s suicide, something he desperately wanted the psychoanalysis to do, but it did mean acknowledging that they shared a relation to violence. He felt closer to his son.

In psychoanalysis, we would say that the death drive of the patient was brought to the surface. Giving it this room is, in fact, healing; we are then able to work on the repression and misrecognition that gives the death drive more strength. You can see it in the memoir as Boothby’s memories of his son suddenly took on an aliveness, as if he was there conversing with him, feeling even the physical weight of his body when he recalled them hugging. This didn’t lessen the pain; in fact it intensified it, showing him what was gone. But it was also a new son, or a new sense of his son, more alive for what he didn’t understand about him, just as Boothby hadn’t understood himself. It was as if the liveliness of the memories was being fueled by the discovery of this gap, bringing him closer to his son than he had ever been. It is this process that he wanted to write about in the form of a book.

What we can see in this is that psychoanalysis gave room to the death drive that was fueling Boothby’s melancholia, marking it through a traversal of memories and fantasies that, as Boothby says, did not correspond to his sense of self, his ego. He didn’t understand that he, too, was violent. He didn’t understand all that he didn’t understand. It’s hard to mark an absence. The work in psychoanalysis takes apart his ego, and with it, the lost object (in this case his son), and these are then put together anew.

In fact, the work with the death drive marks the radical separation of father and son from each other, in life and in death. But this mystery begins to be a source of life, vivacity, and one might even say desire. It is also a moment for Boothby to internalize his son in a new way. This is, in part, the place where he discovered a desire to write this book, and, as he said, continue living and not follow his son into death.

I would like to leave us with this: isn’t it the case that a lot of today’s debate culture accuses the other of violence? Isn’t this the division in speech that proliferates? Namely, how we can justify the utmost violence against the other in the name of attacking their violence? What would it take to know this violence as in ourselves? Know this, but also know what we don’t know. That brings me to what we don’t understand about what we don’t understand, especially in this age of information.

We can google anything, we can watch anything, listen to anything; we can podcast, post, surveil, GPS track, store in clouds, all of it. And yet, we don’t understand much about human life, living together, having babies, raising children, sexuality, education, pleasure, satisfaction in work, dying. We don’t know what to do with ourselves. The cry from my patients about what they should do is at peak volume – ear drums are being blown out.

This is why Boothby’s title is so uncanny—not only the violence of blowing off one’s head, but violence to the head, the attack on thinking and breath. Everything we have accumulated culturally feels as if it’s a hair’s breadth from being blown away, dissolving, being destroyed, not making sense any longer. Things blow. And we are left blown away by all the violence. We have to catch up with the enormity of loss, but it is, at least according to this psychoanalyst, the only source of renewed life, surprise, awe, even extreme gratitude – another way of hearing blown away.

Blowing is also breathing out.

Jamieson Webster is a psychoanalyst in New York and teaches at The New School for Social Research. Her recent books include Conversion Disorder (Columbia, 2018) and Disorganisation and Sex (Divided, 2022). She writes regularly for Artforum, The New York Review of Books, and Spike.

Image credit: © Nan Goldin; courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery