DUCHAMP <3 ROUSSEL Mark von Schlegell on Marcel Duchamp’s Lifelong Raymond Roussel Fandom

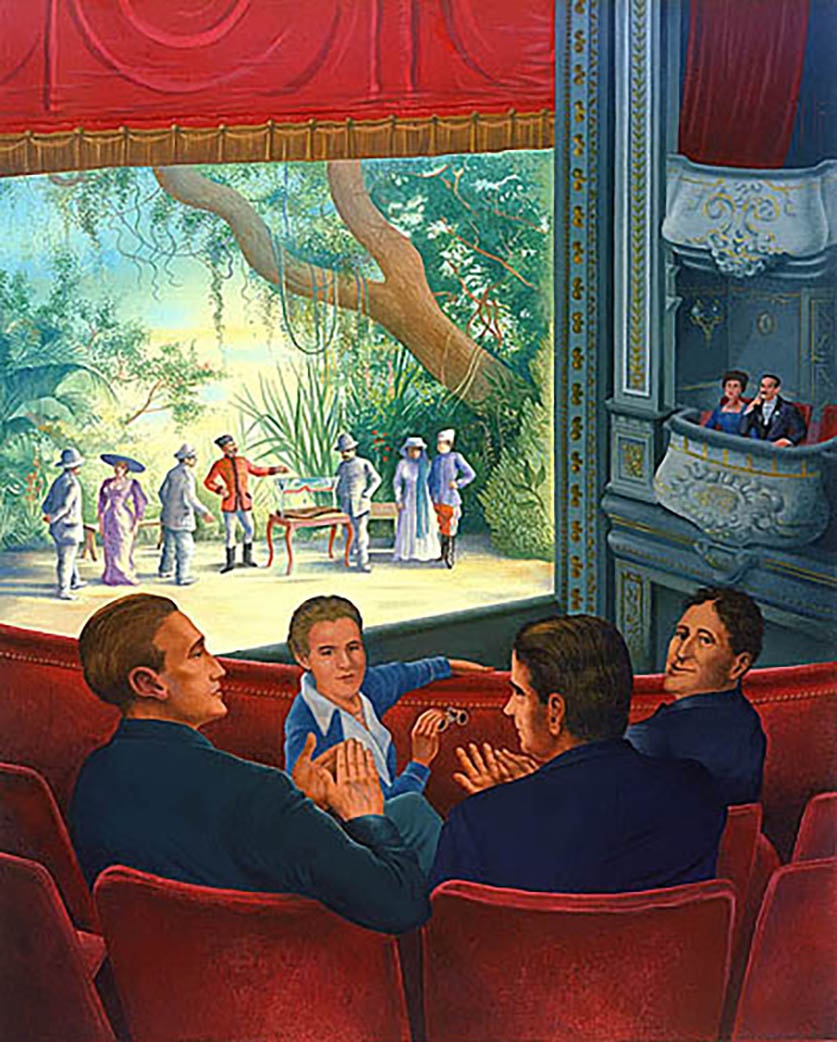

André Raffray, “Marcel Duchamp, Gabrielle and Francis Picabia, and Guillaume Apollinaire at a staging of Raymond Roussel’s play ‘Impressions d’Afrique’, Théâtre Antoine, Paris,” 1977

Marcel Duchamp was not alone in following Raymond Roussel’s work into some of its most radical implications. It’s true that André Breton, Salvador Dalí, Michel Foucault, and other art-world influencers all cited Roussel profusely as they chased novelties in their own works. Their appreciations are for Roussel as a genius outsider, an avatar of “madness,” or a “Great Hypnotist” with alchemical powers. [1] Duchamp, virtually alone among his contemporaries, celebrated the rational and practical Roussel, the enemy of romantic genius.

Remarkably, Duchamp appreciated this widely misunderstood writer decades before Roussel’s posthumous essay “Comment j'ai écrit certains de mes livres” (How I Wrote Certain of My Books, 1935) revealed that the mysterious novels Impressions d’Afrique (1910) and Locus Solus (1914), as well as the plays that followed, had been composed, in their entirety, by an arbitrarily imposed method of banal wordplay. The bizarre incidents and machines described therein were products of the language of haute bourgeois Paris itself, exterior to the writer’s intentions and desires.

In a day that lives already in art history, poet Guillaume Apollinaire took the Picabias and their young friend Marcel Duchamp to balcony seats of Roussel’s play-version of his novel Impressions d’Afrique at the Théâtre Antoine in the spring of 1911. The archaic surface of his work often persuades readers that Roussel was of an earlier generation than the Surrealists, but the facts tell otherwise. In 1911 Apollinaire was 30 years old; Francis Picabia was 32; Roussel was 34.

For the restless 23-year-old painter Marcel Duchamp, the opportunity to be influenced by a writer came as the first revelation:

I saw at once that I could use Roussel as an influence. I felt that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter. And Roussel showed me the way. [2]

Putting bizarre performance and freak machinery on stage (accompanied by curious titles and signage), Duchamp’s Roussel deconstructed the separatism of the arts, grounding them with a new scientifictional, planetary sublime. Roussel showed Duchamp “the power in the creative use of la phantasie ... anything can be done. Especially if you describe it in words.” [3] With this new sense of language’s original power, Duchamp moved exactly from Roussel into sustaining the four-decade rejection of painting that followed. But it wasn’t simply that Roussel led Duchamp to the end of his painting – virtually all Duchamp’s later activities, which opened so many novel avenues of artistic possibility to the wider world, are following Roussel, or acknowledging his previous work in some manner.

In numerous interviews, Duchamp has credited Roussel directly with inspiring the mechanical originality of the Large Glass. Less known is that the first of the sculptural multiples, the very icon of Duchamp as Duchamp, the Bicycle Wheel (1913/1951), began as a visual pun on the writer’s name: roue (wheel)/*selle (saddle; stool). Rrose Sélavy, Duchamp’s cross-dressing alter ego, was also explicitly inspired by the gender play in Roussel’s theater. [4] In the artist pages published in Charles Henri Ford’s View magazine, Duchamp chose to pair himself with Roussel as twin “artiste-inventeurs.” In presenting himself as a super-fan, Duchamp was also emulating Roussel, who described himself as a “fanatic” in regard to precursors like writers Jules Verne and Pierre Loti, and astronomer Camille Flammarion. But as we apply this relation to a revision of Duchamp, it is easy to overlook how our Roussel changes as well by this relation. Duchamp very clearly calls Roussel artiste.

It reminds us that when Duchamp saw what he believed to be authentic novelty at Théâtre Antoine, it was the work of a renegade litterateur who was, in some sense, not writing by doing the play. Indeed, with the 1910 novel hardly able to find more than a single enthusiastic reader, and two early stage versions failing to receive any notice whatsoever, this third incarnation of Impressions was itself a triply perverse refusal to conform. Roussel canceled the end of the extravagant second run in fall 1910. But then his mother died in October of that year, leaving him in command of a great part of the super-fortune a new kind of capitalism had bestowed upon his stockbroker father. Roussel returned to the stage in the spring of 1911, imagining a new confrontational performance without economic constraint.

Despite the naïveté all writers (even Marcel Duchamp) have insisted upon awarding Raymond Roussel in matters of art, it was precisely to the avant-garde that Roussel now turned to secure the destiny literature would deny him. [5] Renting out the elegant and traditionally experimental Théâtre Antoine for a three-show run, he hired Aurélien-Marie Lugné-Poe as director and star – the very Edgar Allan Poe fanatic who first starred in and directed Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi (1896), the work that shattered bourgeois Paris a generation earlier. Lugné-Poe’s hand-picked company of seasoned professionals presented an anti-romantic, purposefully confrontational Impressions d’Afrique – the model of the plays Locus Solus (1922), L’Étoile au front (1924), and La Poussière de soleils (1926) that would follow. Bewildering, absurdist combinations plucked from the Parisian imaginary paraded on the stage, including a giant centipede playing a zither, the severed head of Danton on a plate, a suicide by electrical execution, a one-legged man playing a pipe made from his own tibia, and as the pièce de résistance, the statue of an ancient slave fashioned out of industry-standard whalebone corset stays, wheeled in on rails of calf lung. [6]

Today Roussel’s artist-ness has expanded with the discovery of such ephemera as posters, photographs, objets, manuscripts, and miscellany, all contained in his rediscovered lost archive. An intriguing matter of Duchampian “boxes”: it turned out the ever precise and careful Roussel had put a trove of materiel quietly and safely away before he suicided in 1933. The boxes came to light in 1989, when the ancien Parisian warehouse they occupied underwent gentrification. The archive’s contents are still being published and shown today. The artist who emerges might well be a follower of, not simply precursor to, Marcel Duchamp.

Cabanne: Perhaps the way Roussel challenged language corresponded to the way you were challenging painting.Duchamp: If you say so! That’s great!Cabanne: Well, I won’t insist.Duchamp: Yes, I would insist. It’s not for me to decide, but it would be very nice, because that man had done something which really had Rimbaud’s revolutionary aspect to it, a secession. It was no longer a question of Symbolism, or even of Mallarme [...]. And then this amazing person, living shut up in himself in his caravan, the curtains drawn. [7]

In Cabanne’s “I won’t insist” and in Duchamp’s response, the artist expresses our own impatience with art history’s limited view of Roussel. Duchamp had come to understand Roussel’s life as something like a perfect record of the radically freed imagination, a total artwork in itself. Before the First World War, Roussel had exposed, and escaped, the psychosis of the modern European fetish for the machine. [8] Duchamp perceived that via wordplay Roussel had avoided both romantic and enlightenment traps, transforming even psychoanalysis into an engine of his own devising. “That’s what interests me about Roussel: what unique things he has. It cannot be connected to anything else.” [9]

Despite the surface madness, Roussel’s words lead us not to the depths of the author’s unconscious (his prejudices and attitudes are plain to see) but rather to their own hitherto secreted desires. The unconscious globalism and uncanny depth of language itself have surfaced. This scalar surprise works as reality shock, again and again, without the mimetic ambiguity of the romantic/empirical dialectic. On Roussel’s stage we glimpse the whole monster, the planetary set of possibilities that makes all literary formulations possible. For Roussel this art is not a matter of speculation, conceptualism, or inspiration. Already in his first major work, Mon âme (1897), written at age 17, the special effects come by way of applied labor, by “grimacing workers” deep inside a “strange factory.” Indeed, the labor takes “a people.” [10] This hard work distinguishes Roussel’s experiments. Uniquely, his father’s great fortune put the means of production in the hands of the laborer. And as he worked himself to exhaustion creating his original texts, he exhausted his fortune producing the plays. By 1933, after numerous performances, tours, and revivals – all scandalous failures – 56-year-old Roussel was ruined.

Duchamp: I saw him once at the Régence, where he was playing chess, much later.Cabanne: Chess must have brought you two together.Duchamp: The occasion didn’t present itself. He seemed very “straight-laced,” high collar, very, very Avenue de Bois. No exaggeration. Great simplicity, not at all gaudy.

The truth was, when he began lessons in the game at the Régence, Roussel could afford no greater canvas and was very likely planning for his own demise. It is remarkable to see through Duchamp’s eyes how powerfully and with what dignity Roussel maintained his artistic control of the real, so that in his last months his greatest observer would not associate the late chess-playing with ruin and death. In fact, this memory of the Régence clearly encouraged Duchamp in his own celebrated turn to chess as if to an alternate-universe art form. [11]

Raymond Roussel’s success, the reverse-side of his public failure, reveals how money directly applied transforms the very stage of capitalist-era reality. His plays in many ways jump-started Dada and Surrealism, the first major movements to move beyond Cubism in the 20th century, his novels the nouveau roman, his poetry the New York school and its derivatives. But the failure and ruin remained very much attached to Roussel’s legacy. Duchamp did not make the same mistake. His quiet victory over art history shows lessons he was sensitive enough to learn observing Roussel.

In his description of the dandified Roussel, Duchamp might have been describing his own strikingly comfortable but understated look after he had found his own source of nearly infinite wealth. To work similar effects over art history, Duchamp would also need access to the full might of applied capital. New York, where he moved to exploit the scandal of his Nude Descending a Staircase at the 1913 Armory Show and stayed to escape the war, introduced him to just the thing: American collectors.

Duchamp met his first rich backer when Walter J. Arensberg – like Raymond Roussel, the windfall inheritor of a lucky father’s absurd fortune – purchased the Nude in 1919. No doubt Arensberg, an obsessive believer in Lord Bacon as the secretly revealed author of Shakespeare’s plays, appreciated the Renaissance aura of Duchamp’s quasi-scientific, Rousselian project. He helped make possible Duchamp’s own dandyist pose, with which it was possible to cover over a multitude of creative endeavors. For it turns out, of course, that Duchamp himself labored all those years he feigned non-production – in a secret studio accessed through a hidden door in his townhouse. Today we are still making sense of the posthumously revealed Étant donnés (1946–66), and numerous multiples, mechanicals, and powerful ephemera.

Perhaps I go too far, but according to this fantasy, Duchamp’s courting of inheritors of great New York fortunes awarded him an art historical influence comparable to, and to be contrasted with, Roussel’s over his own generation. Found object art, pop art, conceptualism, and post-conceptualism readily claim Duchamp as progenitor. He also helped pioneer the transatlantic dynamics of the coming “art world” by serving as a private dealer of Brancusi’s sculptures in the United States, and as trusted advisor to curators of the first collection for the Museum of Modern Art. When he went so far as to celebrate and alter some of Brancusi’s stands, he helped get minimalism off the ground.

A reader of Mark Fisher might judge Duchamp’s turn via Roussel to advanced capitalism as the Achilles heel of his future reputation. It is hard today to understand his work without explanation, and art historical intervention, which is also to say without the economic systems that continue to pay the bills for its celebration. Roussel, however, remains underground, enmeshed in the more subcultural and extra-economic field today afforded to the literary. In a fashion still not roundly appreciated, his writings remain full of possibility, variation, and surprise – including the fact that by the time he died he was quite realistic about their fate. [12]

It seems Roussel’s naïveté has always been a projection of the current art historical unconscious onto its own project. The work remains curiously fresh and up-to-date.

“Roussel delivered me from the whole ‘physico plastic’ past.” These striking words from one of Duchamp’s earliest interviews reach out to us in 21st-century digitalia with precocious futurism. [13] What Duchamp called in Roussel la phantasie was a zone like the Vohrr in Impression d’Afrique, an artificial world made possible by the multiversal impulse of language itself, wherein real transformations and novelties occur by definition. Now that artificial intelligence begins to interfere with our cultural understanding, it becomes newly apparent how Roussel, by means of his carefully applied method, and Duchamp, as a follower, gain access to “ideas from a non-human world” by means of a curious collaboration of human and artificial intelligence. [14] This artificial intelligence belongs to language itself, at its most banal. Augenblick as alltime: for woven into the casually punned statement are all the tissued invisibilities, the unnamed names, unstated identities, and unrevealed organizing concepts, expanding gleefully unburdened of ambiguity – typically slain by any utterance.

In the internal light of this exposed realm beyond the real, “comparable machines,” as Michel Butor says of Roussel’s fictive inventions, “can always be elaborated.” [15] For Roussel and Duchamp, word games reach out to take us aways ever further from the author’s intention into artificial intelligence. Procėdė, French for “method,” emphasizes this mono-directional, algorithmic continuity. Roussel’s “inventions” mechanized a process that allows the collective cultural unconscious of language to articulate itself in literature. The author’s role here is entirely negative: hiding one’s own absence, smoothing over transitions, fitting into narrative and image, editing. The planetary scale of the all-tongued unreal that remains dwarfs the romantic sublime.

But all was not method. It’s worth remembering that Roussel wrote other major works throughout his life, poems not composed by the method, but theoretically related and similarly original. He produced book-length poems like the magisterial Nouvelles impressions d’Afrique (1932) in the spirit of Renaissance conceptions of the poet as master observer and epic craftsperson. Marcel Duchamp also remained to the last, and in the Renaissance sense, a painter, an ambitious artist full of personal quirks and flashing secret revelations – like Da Vinci, the Renaissance artiste-inventeur he memed in L.H.O.O.Q. (1919). Even as Étant donnés holds the torch for virtual reality possibilities its contemporaries had not yet clearly formulated, it also points the way to the solution of the Black Dahlia case, that most fiction-like true crime of LA noir history. It is now widely assumed that the infamous 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short and placement of her dismembered body was a madman’s message to the masters by LA Surrealist fan and Man Ray hanger-on George Hodel. Marcel Duchamp knew him personally. [16]

But a different kind of magazine will have to open that can of worms.

Among other things, Mark von Schlegell is the author of Venusia (Semiotext(e), 2005), honor's listed for the “Otherwise Prize in Science Fiction,” and of the critical essay “Roussel Returns” (Semiotext(e), 2016).

Image credit: Collection Francis M. Naumann and Marie T. Keller, Yorktown Heights, NY

Notes

| [1] | “André Breton, “Raymond Roussel,” Anthologie de l’humour noir (Paris: Éditions du Sagittaire, 1940). |

| [2] | Interview with James Johnson Sweeney, “Eleven Europeans in America,” Museum of Modern Art Bulletin 13, nos. 4–5 (1946): 20. |

| [3] | Ibid. |

| [4] | “Raymond Roussel influenced the Glass and Rrose Sélavy, demonstrating to me the power that lies in the creative application of imagination”; Marcel Duchamp interview with Lawrence S. Gold, 1958. |

| [5] | “Roussel knew nothing of all that”; Marcel Duchamp interviewed by Pierre Cabanne, 1966. In: Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Da Capo, 1971), 34. |

| [6] | “It was fantastic. There was a manikin on stage and a serpent which moved a little. It was absolutely the madness of the extraordinary.... He used puns, some good, some terrible. The latter might have been the best of all.” Marcel Duchamp interview with Lawrence S. Gold, 1958. |

| [7] | Interview from Cabanne, Dialogues, 34. |

| [8] | “Of course [The Bride] takes part in an attitude towards machines, an attitude that is by no means admiring, but rather ironic, which I share with Raymond Roussel, like the performance of Impressions of Africa...”; interview with Michel Sanouillet, 1954. |

| [9] | Cabanne, Dialogues, 1966. |

| [10] | “Mon âme est une étrange usine / Où se battent le feu, les eaux, / Dieu sait la fantasque cuisine / Que font ses immenses fourneaux. / C’est une gigantesque mine / [...] Avec des bords monumentaux” (lines 1–8); Critics have looked back on these lines as displaying almost crude egoism, but the soul they describe seems much like language itself. |

| [11] | Unlike Roussel, Duchamp had a long history with the game. He was a child champion, a real master in later life, and several of his early paintings feature chess pieces. I am not convinced Roussel was the quick-learned chess master he would claim to be in “Comment j’ai écrit certains de mes livres.” |

| [12] | His last published words, the end of “Comment j’ai écrit...”: “And I take refuge, for lack of anything better, in the hope that I will perhaps have a bit of posthumous fulfillment with regard to my books.” Translation by Trevor Winkfield. |

| [13] | A letter to Jean Suquet, 1949. |

| [14] | In Pierre Janet, “The Psychological Characteristics of Ecstasy,” in Raymond Roussel: Life, Death and Works, trans. John Harman, ed. Alastair Brotchie et al. (London: Atlas Press, 1987). |

| [15] | Michel Butor, Essais sur les modernes (Paris: Gallimard, 1964). |

| [16] | See Steve Hodel’s Black Dahlia Avenger: A Genius for Murder (New York: Harper Collins, 2003) for an introduction to Marcel Duchamp’s relation to the probable killer, or listen to the podcast “Root of Evil: The True Story of the Hodel Family and the Black Dahlia,” directed by Patty Jenkins (TNT/Cadence13, 2019). |