OTHERNESS AND RESILIENCE Ana Magalhães on the Brazilian Art Scene during the COVID-19 Pandemic

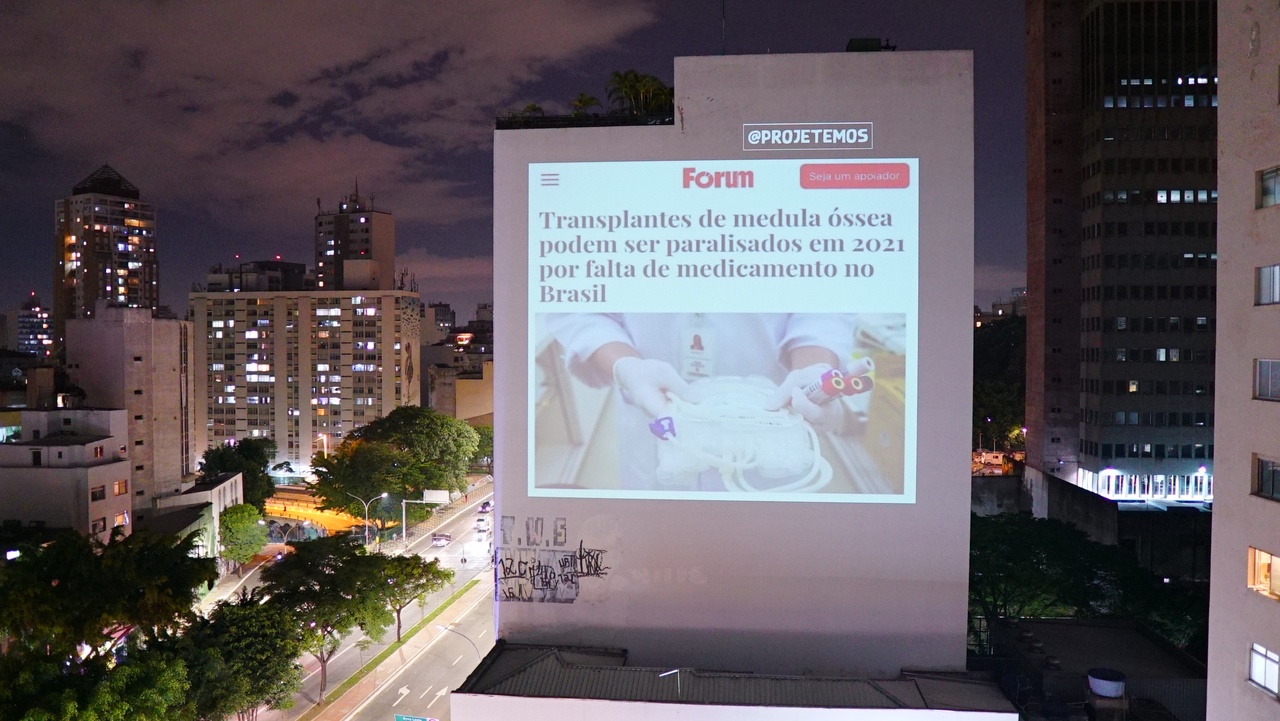

Projetemos, Façade projection in São Paulo, 2020.

Whether the events that followed the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 will have any positive outcomes in a country like Brazil remains a far-fetched idea and very difficult to imagine. Since 2016, Brazil has plunged into a vertiginous descent that one could call a grotesque 21st-century version of the Dark Ages. After almost three decades of democracy, the country fell prey to extreme-right-wing politicians who paved their way to the presidency through the support of militias and religious-fundamentalist groups. These groups have long been present in Brazilian society and they represent facets of a nation that has never atoned for its colonial past or for the horrors of its recent military dictatorship (1964–1985).

Since the inauguration of President Jair Bolsonaro in January 2019, Brazilian society has seen the mass destruction of the country’s natural resources and environmental preservation areas, the genocide of Indigenous communities, and the rise in rates of femicide and attacks on LGBTQ+ communities, as well as the rise of violence against people of African descent. Such tragedies in everyday Brazilian life have also affected science, culture, and the arts. Not only has there been a systematic attack on the most important universities and research institutions in the country, but policies for educational and cultural programs have been completely dismantled. The COVID-19 pandemic and the Brazilian government’s neglectful handling of it have only worsened the situation. President Bolsonaro dismissed the seriousness of the situation by making public declarations against the very health policies that would have helped Brazil face it. This stance left the country without a minister of health for a full month during the first period of the country’s lockdown after Bolsonaro fired the sitting minister over disagreements about social distancing measures. After many conflicts and an outcry from the public and civil society, the president then appointed a general from the Brazilian armed forces with no previous experience in health policy to run the ministry. The president’s decisions and behavior in such a situation will turn the country into a pariah in the game of nations. The attack on scholarly discourse can only be compared to the actions of the Inquisition at the beginning of the modern era. No event could more sadly but perfectly foreshadow the coming Bolsonaro administration than the September 2018 fire that destroyed the greater part of the collections and building of the oldest museum in the country: the National Museum, which held the most important ethnographic and natural history collection in Brazil, and which today belongs to the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Giselle Beiguelman, "The Book After the Book," 1999, (restored version for Web 2.0, 2019).

Despite this situation, innovative thinking and important transformations have been emerging in Brazilian art museums and institutions over the last year. Here, I would like to address two developments I understand as milestones in the renovation of the Brazilian art system.The first is the representation of otherness, which has become a vital component of curatorial work. Some museums and institutions have dedicated exhibition programs to issues of African-Brazilian heritage, Indigenous contemporary art, and gender diversity, as well as conducted thorough research into Brazilian women artists. These trends started around 2015 and 2016, and in the last two years they have grown not only to serve as the basis for temporary exhibitions, but also for art museums to hire curators from these communities. A noteworthy example is the appointment of the young African-Brazilian curator Keyna Eleison to become chief curator of the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art (MAM Rio), alongside curator Pablo Lafuente. Eleison was selected by a committee of experts concerned with the need for art institutions in the country to diversify their curatorial staff. Some institutions, mainly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, have recently been hiring African-Brazilian and Indigenous curators. This is the case at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) and the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. However, Keyna Eleison’s position at MAM Rio is worth highlighting because she was brought on not to develop a temporary exhibition program but rather to join the permanent staff. That she is both a woman and African-Brazilian is quite exceptional in the landscape of Brazilian institutions. Although Brazil has many curators and art critics who are white women, some of whom having already led important art institutions in the country, they are still few in number relative to their male colleagues. [1] Additionally, before Eleison there was only one African-Brazilian chief curator at any major art institution in the country: the artist Emanoel Araújo. In the early 1990s Araújo was key to transforming and updating the program of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. Since 2004 he has been the artistic director of the Museu Afro Brasil at Ibirapuera Park. [2]

Now there is a younger generation of African-Brazilian and Indigenous curators, scholars, and artists developing various exhibition programs all over the country and making a significant contribution to the study of the history of visual arts in Brazil. [3] Their presence can only be attributed to the fact that in the first two decades of the 21st-century the country made major investments in the system of federal universities across the 26 Brazilian states. This support provided access to international and high-quality academic research resources for the first time and allowed these new thinkers to contribute locally to higher education institutions while also fostering the creation of new art institutions outside of the São Paulo/Rio de Janeiro axis.

Projetemos, Façade projection in São Paulo, 2020.

2020 was also the year in which Brazilian art institutions went digital, so to speak. Digital art in the country can be traced back to the 1990s, when the first generation of Brazilian artists engaged with the rise of the internet and the virtual world were completely up-to-date with what artists and art institutions were doing in the so-called first world. [4] However, these artistic practices are not well represented in art institutions, which are at pains to understand how to document and preserve digital artifacts, [5] and because debates around digital and media art have generally taken place quite separately from contemporary art discourse and curatorial work. [6] When art institutions had to close their doors because of the pandemic, they began generating online programs for their audiences. These included live art education programs, “viewing rooms,” and online exhibitions, as well as short-term courses on art and contemporary world topics.

Such initiatives elicited two consequences. The first is the transformation of art institutions’ social media and websites. Initially these were understood primarily as information and publicity tools, less interactive, and certainly less geared toward mediation with art audiences. Now it has become clear that even with the reopening of their venues and reception of their physical audience, institutions will not stop exploring the many possibilities of the virtual dimension. The second consequence is the continued development of the digital as a curatorial tool. These initiatives will encourage artistic and curatorial projects to create digital platforms and virtual realities, as well as address their audiences through social media. The latter involves new ways of communicating and researching the culture of memes, the circulation of self-made videos and images, and selfie culture.

Regarding the potential of digital media, the most interesting project Brazil has seen in the last year is that of Projetemos. [7] This collective was created by a group of artists, cultural agents, and VJs (among them, VJs Boca and Mozart from Recife in the Northeastern state of Pernambuco). Their aim is to engage people all over the country in sharing their projection equipment to allow Brazilian society to assert itself against social, economic, and political distress. The collective’s website lets people enter phrases and protest slogans that representatives of Projetemos then project onto the façade of buildings in various cities in Brazil. Through this activity, the collective provides a means for Brazilians to organize virtual protests and resistance during the pandemic. They have also started organizing virtual workshops to teach people how to use projectors for this project, creating a powerful, organized network in civil society that can express a critical political voice in response to the country’s fraught situation. The collective represents the hope that we can change the state of things in Brazil and that Brazilian culture still maintains the capacity for transformation.

Ana Magalhães is an art historian, curator, professor, and the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

Image credit: 1. & 3. Courtesy: Projetemos & VJ Mozart 2. Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Courtesy: Giselle Beiguelman

Notes

| [1] | It is worth also mentioning the art critic and historian Aracy Amaral and the art educator Ana Mae Barbosa. These two curators, both educated in the early 1970s, have played a fundamental role in art historiography in Brazil, while also directing some of the most important art institutions in São Paulo. Aracy Amaral was involved in the Latin American Biennial of 1978 (organized by the São Paulo Biennial Foundation) and later became the director of Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo and the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP). Ana Mae Barbosa made a vital contribution to federal educational policies for the arts in the early 1980s and was the director of MAC USP after Aracy Amaral’s tenure. |

| [2] | The museum was established through the donation of his own collection of African-Brazilian objects to the State of São Paulo. |

| [3] | See, for instance, the projects curated by Diane Lima, artist Rosana Paulino, and artist and professor Renata Felinto, among others. For a comprehensive list of African-Brazilian and Indigenous curators in Brazil, see Luciara Ribeiro, “Curadoras e curadores negras, negros e indígenas, Brasil,” first published in October, 2020. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y5y8jvem. This is part of Ribeiro’s research as part of the Projeto Afro collective. See: https://projetoafro.com/. |

| [4] | Of note here is São Paulo artist and scholar Giselle Beiguelman’s net art project The Book After the Book, from 1999. With this project, Beiguelman took part in ZKM Karlsruhe’s Net_Condition festival of net art that same year, being the first Brazilian artist to have a net art piece in international collections. An updated version, for Web 2.0, now belongs in the collections of MAC USP. In 2016, Beiguelman made a donation of six works to the museum, making MAC USP the first institution in the country to collect digital art. The project is available at: https://acervo.mac.usp.br/netart/giselle_beiguelman/thebook/. |

| [5] | Brazilian art institutions are not yet prepared in terms of infrastructure to preserve digital artifacts. This is very expensive and Brazilian institutions do not have the budget for it. The country’s internet and mobile phone systems received major investments in the last decade, however, which has made Brazil one of the most digitally connected countries in the world, despite its deep social and economic inequities. |

| [6] | Even in terms of video art, there was a development of festivals and events that grew apart from art museums and art institutions. This is the case of the festival Videobrasil. See: http://site.videobrasil.org.br/en/. Established in 1983, it was rebranded in the last decade as Festival Videobrasil of Contemporary Art. See also Festival FILE (www.file.org.br), whose last edition took place in 2019. |

| [7] | See an interview with founding VJs Boca and Mozart in Arte Brasileiros! at https://artebrasileiros.com.br/arte/cidade/projetemos-isolamento-social-coronavirus/ (in Portuguese), and the collective Instagram profile at https://www.instagram.com/projetemos/?hl=pt-br. |