GAMING DESIRE Gracie Hadland in conversation with Stephanie LaCava and Chris Kraus on “The Superrationals”

Gracie Hadland: The Superrationals is the story of a young woman, Mathilde de Saint-Evans, trying to identify herself, her desires, and her ambitions in and around the New York and European art worlds of the 2010s. The book is told through multiple characters; perspectives and timelines are constantly shifting and overlapping. What prompted you to write this story in this way? Had it taken on any other forms before the structure of a novel? What was important for you to be getting at in this book?

Stephanie LaCava: I started research for the book seven years ago with texts around Freud’s “Uncanny,” like E. T. A. Hoffman’s “The Sandman.” I knew I wanted to tell a fictional narrative that tackled questions of desire and the unconscious hidden in a creepily familiar superficial world. I started off wanting to plot the story in the form of an anagram, so that you could fold it onto itself. It would have been almost as if you could turn the book over and read it the opposite way or open it to any section and read the narrative in any order. This kind of Oulipian restraint fell away, but it’s still there in this idea of repeating our parents and reliving the same patterns. Mathilde is stuck in a system trying to find her way out, haunted not only by her mother but by a legacy of storytelling that punishes women like her.

Hadland: I think the first section and last section are untitled, whereas others are titled with the name of the narrator for that section, as if to suggest the central character could be any of them. When I first read it as a PDF there were no page numbers, so I would get confused about which narrator was speaking. There weren’t always distinct styles that made them easy to tell apart; rather, there was more overlap, as if they were interchangeable.

LaCava: Yeah, it’s this kind of thing where it could have started at the end. The timing is a bit mixed up. And everyone’s almost interchangeable. Some people would say that’s not a good thing, but I think if it has a purpose, and even when it’s disorienting, that can be really interesting.

Hadland: Chris, you edited the book. What drew you to this story and how did you see it fitting in with the Semiotext(e) publishing record, particularly the Native Agents series? Could you talk a little bit about the series’ inception?

Chris Kraus: I just think Stephanie is a wonderful writer. The Superrationals unfolds through a brisk narrative, but Stephanie makes all of these shrewd and knowing observations along the way. There’s such a dramatic contrast between the sophisticated, light art world Mathilde moves in and the gaping hole left in her life by the loss of her mother. I immediately associated the book with a certain lineage that began (at least for us) with Michèle Bernstein’s All the King’s Horses, but that’s not why I wanted to publish it. The Native Agents series has changed a great deal since its inception in 1990. Initially, I felt like I had to create an intellectual justification for publishing, basically, my friends — and so I presented the series as a mirror world of French theory, of subjectivity-in-practice. Since Hedi El Kholti joined Semiotext(e) in 2004, we’ve co-edited the imprint and it’s a lot harder now to define.

Hadland: Stephanie, were these characters people you’ve been revisiting and exploring in other things you’ve written?

LaCava: No, not really. In a way, my first book, An Extraordinary Theory of Objects, makes more sense in this context. Memoir in the publishing world is like the cookbook: it’s what sells. It can be seen as a joke in a way: coming of age, expatriate in Paris, etc. Mathilde’s background is similar. It’s like a conceptual project in reverse. Now, maybe I’ve been able to write the book that investigates the shaping of this girl on a psychoanalytic level. And where she ended up in a system, in the world, at a certain moment in time.

Hadland: I believe that’s the case with Bernstein’s book All the King’s Horses. She wrote it as a kind of commercial product so that she could fund her other work, aware of the fact that young women sell and they also consume, and sort of playing with that.

LaCava: I like that book as an example of how publishing and writing can be two different things. A self-aware protagonist is talked about as the ultimate millennial author move, right? What about writing the opposite, but with a self-aware hand? In the same way, Mathilde’s thesis, which is excerpted in the book, is not supposed to be a knock-out academic work of art-historical relevance: it’s meant to be bad.

Hadland: Right. How do you expect the reader to get that? To be in on it instead of taking it at face value? Or is that not really your concern as the author?

LaCava: It becomes some kind of performance, the different reactions to it. But that’s more if you veer into the conceptual aspect of fiction; that’s not a very literary conceit. In his writing, Mike Kelley talks about how artists can retroactively co-opt what critics say about their work. We’ve all seen it happen. Mathilde is reading Kelley as she writes.

Hadland: The character of Mathilde is a familiar figure: the millennial heterosexual woman who is blasé, kind of cold, and exhibits a kind of disaffection brought on by overachievement and privilege. She’s somewhat precocious in a way that endears her to men but repels women. What is the appeal of this figure? What is her power? Does she still have power?

LaCava: I am haunted by this woman. She’s the same one that’s a cipher on screen or silent in a magazine. I think her power is changing and in this narrative it is, in part, what brings you back in time to, say, 2015. It’s funny because the mother is meant to be this sort of ideal. It doesn’t match up to right now but is of a certain moment in time, the ultimate selling (and consuming) vessel, this cold swan.

Hadland: I’m also haunted by this woman. There are so many iterations of her in the Semiotext(e) canon of fiction too. Why is it that this figure is revisited again and again? Is she still as radical as she may once have been?

Kraus: I think the jeune fille is a genre, and as such it’s no more inherently radical than any other genre – rom-com or true crime or science fiction. Definitely the “coming-of-age” story is a trope in Western literary fiction, and the jeune fille figure turns it a little bit on its head. She’s a figure of rage; she’s the ultimate consumer. I think all character tropes are potentially radical if they’re stretched to the edges and the truth beneath the cliché is revealed.

Hadland: I’m thinking about Ottessa Moshfegh’s protagonist in My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018), or Natasha Stagg’s protagonist in Surveys (2016). Both are suffering from a kind of late-capitalist malaise that I feel like has defined the young woman character of recent cultural output. If we’re thinking about the jeune fille as the ultimate consumer, this iteration of her is a woman who is aware of her role in the culture and is both disturbed and exhausted by it, resulting in a kind of apathy.

LaCava: What’s interesting about those books is that they’re both written with a kind of self-awareness about their context. Ottessa gave a great interview in the Guardian, where she says something like, and I’m paraphrasing, “Yeah, I’m trying to game the bestseller.” That’s what I was saying above: this awareness of creating a book to publish. I think this figure’s relevance persists because she’s essential to attention and seduction.

Hadland: I think she’s a figure of irony influenced by the internet. The distance between an internet personality that’s self-aware to the point of irony and then the distance between that person online and off gets smaller and smaller. Which is kind of dark. . .

LaCava: Maybe that goes back to succès de scandale and the gossip. Are people gaming attention so that they can do something else? Can someone claim they’re being ambitious and then turn people’s eyes to something that’s a greater cause? Of course they can, but it has an underbelly. This is kind of like Kim Kardashian going into jail reform. Or yesterday, Paris Hilton was on that Sunday morning talk show claiming she masterminded everything. How much of it can you control? How much can you then co-opt?

Hadland: I think that’s a good point about the game getting away from you and taking on a life of its own. Maybe that relates to the idea of the unconscious too. Then I’m thinking about how Geneviève in All the King’s Horses is an earlier iteration of this kind of figure but maybe taking on a different tone. As the one woman among these heavy male artists and intellectuals, she takes pride in her ability to get their attention and schemes to sort of play them back.

LaCava: That’s totally what Mathilde is doing as well with Charles the dealer, Christopher the writer, Tom the artist.

Hadland: That’s the thing that’s always disturbed me about these characters – women playing this game that inevitably backfires or gets away from them and then they start to comply and that’s when the apathy sets in.

LaCava: I mean, that’s the underbelly of so many cultural success stories. What’s the creator’s backstory? This book is very aware of that living currency of not only sexuality but certain optics.

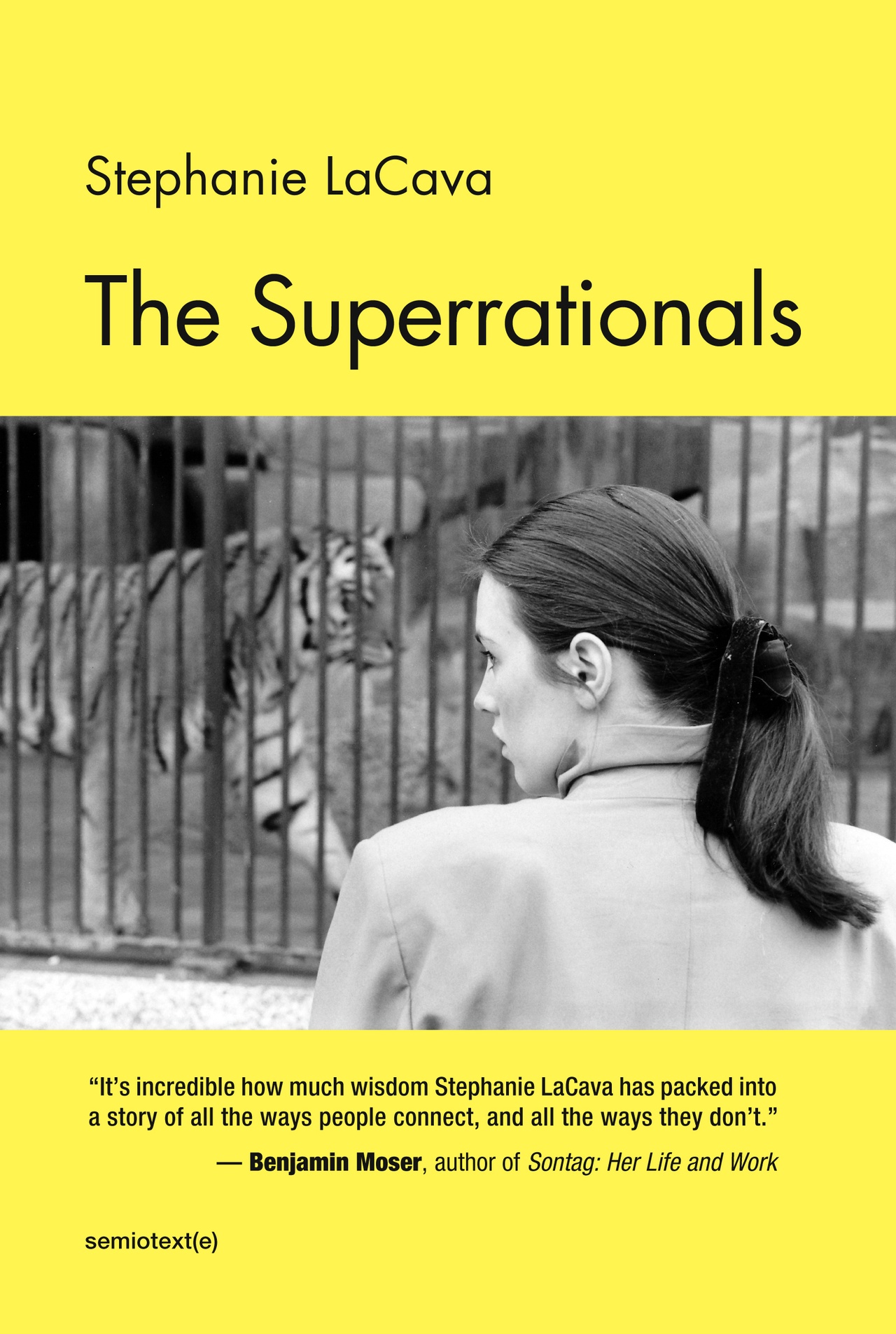

Hadland: I love the Hervé Guibert photograph on the cover and that it makes such a subtle reference to the photo described in the novel, of the black hair ribbon. A fraught relationship to images and photographs is a recurring theme in the novel. This also seems congruent with the French avant-garde you reference throughout. Mathilde writes of Duras: “Duras creates pictures as ciphers, ingress to complicated thoughts and drives.” Whenever I’m reading a book, I’m looking for something visual to hold on to and this image seems so precise. Could you talk about this a bit?

LaCava: To me, that was the craziest thing that happened. I literally found that photo months after the book was complete. It was so strange to me because it was like I had written that photograph. The hair ribbon, and it’s in the Jardin des Plantes as is the photograph in the book. I had never seen it before; it just blew my mind.

Hadland: That’s wild!

LaCava: And then I guess it stumbles over to the psychic intuitive quality that exists in all kinds of art. There were a few of these kinds of uncanny coincidences between reality and fiction. The book isn’t autofiction. It’s fiction, but it wrote itself into reality in ways I didn’t realize. Again, the retroactive thing. It’s also the image that’s now going to circulate on Instagram, for example, to become synonymous with the book. The piece of proof multiplied. And that the book ended up at Semiotext(e) and Guibert being in the family, it made even more sense.

Hadland: I also love that there’s this great connection between the photograph in the book and the photograph on the cover but the photograph in the book represents a missed connection or abstracted connection between the two central characters, Robert and Mathilde. It almost exercises a trope of a mainstream novel of having this object bring two characters together but it sort of does the opposite.

LaCava: And then it connects the reader to the larger presentation of the book. But I can’t totally take credit for that since I didn’t know about that photograph. There were a few moments like this that felt magical or otherworldly surrounding the made-up story and then events that happened in real time.

Stephanie LaCava, The Superrationals (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2020).

Stephanie LaCava is a writer based in New York City.

Grace Hadland is a writer and critic based in Los Angeles. Her writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Frieze, Spike, Momus, and the Believer.

Chris Kraus is the author of four novels, including I Love Dick and Summer of Hate; two books of art and cultural criticism; and most recently, After Kathy Acker: A Literary Biography. She received the College Art Association's Frank Jewett Mather Award in Art Criticism in 2008, and a Warhol Foundation Art Writing grant in 2011. She lives in Los Angeles.

image credit: Semiotext(e)