A Structure: When the Same Things Keep Coming Up by Ramaya Tegegne

Life doesn’t frighten me

What I would like to share with you today is an account of litigation that is resonating with what artists and art workers are going through right now, and that too many of us had actually been going through even before this crisis. To the present day, the case has not been resolved. A year and a half ago, a project I was involved in was abruptly cancelled without any valid reason. We were a small group of women and one non-binary person, including three people of color, all of whom are artists and art workers. We had been commissioned by a feminist festival in Geneva to do an art project on violence towards women, transgender, and non-binary people in the public sphere. Because our project wasn’t ‘unifying’ enough, it wasn’t what the festival directors were ‘expecting,’ it was therefore cancelled, just like that, without any possible adjustment or discussion. When a project is cancelled by the contractor without any fault on the part of the contracted parties, the latter must receive the full amount of the promised wages. Still today, we are struggling to get paid.

We did not have any written contract, though we did have an informal agreement and fragments of a contract in email correspondence. When our project was cancelled, it turned out that this blurry contractual situation was to the benefit of the institution. Indeed, a lawyer friend and various free legal advice services for artists gave us opinions that were at once very confident and contradictory about what we should do. Difficult to know who to believe and what chances we had. In any case, with no strong guarantee that we would be able to win, we could not afford a lawyer, and we did not trust a justice system that is objectively racist and sexist.

So we gave up the legal route and spent many more weeks trying to find other ways to defend ourselves: we made an appointment with the festival directors, our arguments fell on deaf ears; we wrote to the board of the festival, we were told two months later that the directors had acted “with consideration, understanding and respect” without the board’s even having heard our side of the story; and finally, we met with the funding body of the project, a government fund for equality and diversity, who redirected us to the festival to settle this conflict. We were, at that point, completely washed-out and worn down. “Exhaustion can be a complaint management technique: you tire people out so they are too tired to address what makes them too tired,” as Sara Ahmed put it so well in the latest post, “Complaint and Survival,” on her Feministkilljoys blog. She was, by the way, invited to the last edition of the festival.

As women, non-binary, racialized artists and art workers we are already in a precarious financial situation. This cancellation had a direct effect on us. It is revolting to witness a self-proclaimed feminist festival being absolutely unable to question its own behavior and what it is reproducing, while inviting the finest line-up of current feminist voices every year and proclaiming loud and clear to bring women’s work to the forefront. The collective We Are Sick Of It released a manifesto claiming being sick of “an art world that, on the one hand, deals ‘critically’ with migration, racism, colonialism, etc. yet reproduces discrimination at the same time;” and being sick of “the fact that people talk to us, but then make our perspectives and voices invisible. That we are invited, but are only interesting as long as our criticism does not interfere with the everyday praxis of the institution/person, but instead helps them improve their image.” I am sick of tokenism.

I think the reason we’ve made it this far is that, for once, we were a team, and not just alone facing all this. Our group, that has definitely been our strength. Together, we were able to discuss the events, unravel the injustices, to give each other the courage to continue the fight, and split up our resources. But most importantly, we were able to laugh together at the absurd contradictions between the public image and backstage practices of this festival, which quite clearly has a different conception of feminism than we do. But I think what we mostly realized was the tremendous importance and dependence of an entire sector on reputation. In the art field, artists are indeed almost always chosen (for grants, projects, funding, exhibitions, residencies, etc.), and in Switzerland artists are chosen almost exclusively by white people, white jurys, white curators. Rocking the boat has an impact on this selection process, therefore on our careers.

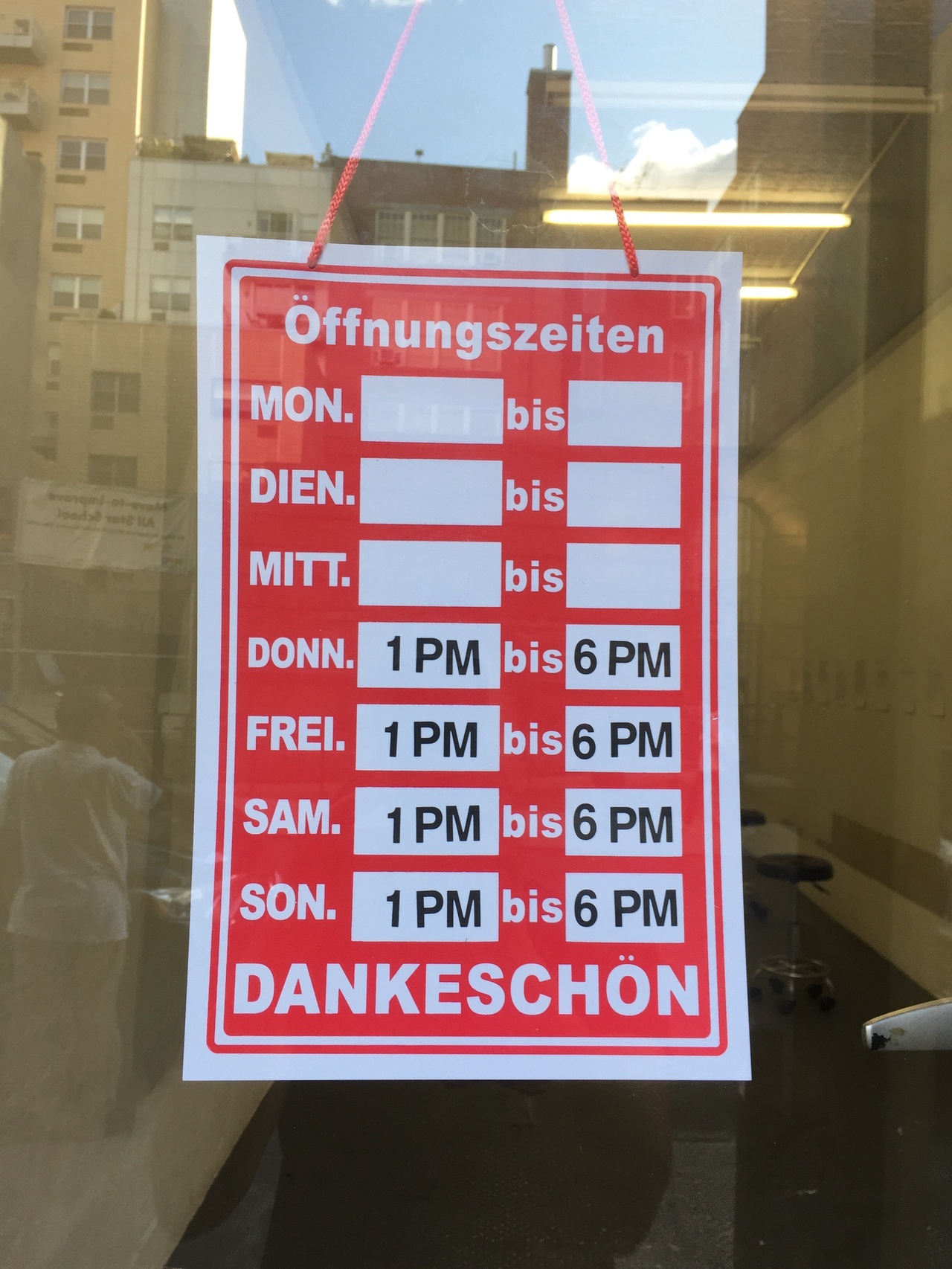

Business Hours of Ludlow 38

The brutal cancellation of our projects as a consequence of the current health crisis, and the difficulties, if not the impossibility, of getting paid for the planned projects; the unaccountability of art institutions; and the contradiction between public discourse and practices: we are now almost all confronted with this. Today, I myself am in this situation again, as are many of my friends.

Sharing information between all the artists involved in a project, asking for transparency on the budget, asking for a contract, a remuneration, BEFORE STARTING TO WORK (in capital letters as a reminder for myself) is fundamental, and the beginning of a better treatment from institutions. But even so, these are still sensitive requests to make when one is alone dealing with an institution, especially for young artists at the beginning of their careers, already happy to have been invited and scared to be labeled as ‘difficult’.

To overcome this isolation, three years ago I myself launched a campaign that became a collective, Wages For Wages Against, for the remuneration and better working conditions of artists and for an alternative and fairer art economy in Switzerland. Unfortunately, we don’t have the resources to be a union per se, but the fact that we have written a manifesto available online that clearly states our demands is already a step toward the collective, and it can help artists to formulate demands themselves. It is a first move to pass the refusal on. We have also organized, participated, and contributed to a number of discussions, workshops, presentations, actions, and collective initiatives. All these projects have, almost every time, shown some actual results and given us more strength to continue evolving in this art field that is far too exclusive, too white, too male, where the exploitation and mistreatment of art workers, artists, employees, subcontractors is the norm, resulting from a generalized neoliberal, racist, colonial, heteropatriarchal, ableist, and ecocidal regime that produces schizophrenic, contradictory, and pathological practices. Because of those who came before us, such as W.A.G.E., we were able to imagine this campaign. And now, because of initiatives that were developed more or less at the same time as we did, such as Garage, Nous Professionnellxs, and Artists Rights, in Switzerland; La Buse, Économie solidaire de l’art, Documentations, ForTune, and Art en grève, in France; Engagement and Caveat, in Belgium; We Dey, in Austria; We are sick of it, in Germany; Coop Fund and Decolonize This Place, in the USA; and many many more, we can continue to grow and progress together.

It can never be repeated enough that this current crisis is unquestionably bringing to light the abysses and fractures of this system. While it is amazing to see so many initiatives of solidarity emerging here and there over these past weeks, I sincerely hope that all these good ideas will prevail far beyond this situation. I hope that together we will continue to develop new forms of solidarity and cooperation, to create associations, unions, cooperatives, supporting funds, and so on. We must now prepare for what comes after. “Complaints can still be picked up and amplified by others. [...] Each complaint gathers more, a gathering as a gathering of momentum; the sounds of refusal [...]. We gather, becoming that momentum.” – Sara Ahmed

For the writing of this text, Texte zur Kunst offered me as remuneration a choice of one of their artists’ editions, worth a maximum of 450 euros.

Ramaya Tegegne is an artist and cultural organizer based in Geneva, Switzerland. In 2017 she launched the campaign Wages For Wages Against. She is currently co-running the art and critical thought bookshop La Dispersion in Geneva.

Image credit: Ramaya Tegegne (the first image shows Life doesn’t frighten me, 2018, Édition Seghers, based on a poem by Maya Angelou, drawings by Géraldine Alibeu)