Turn On, Tune In, Cop Out by Steven Warwick

Sorry Punks!

“As they turned away from agonistic politics and toward technology, consciousness, and entrepreneurship as the principles of a new society, the communards of the 1960s developed a utopian vision that was in many ways quite congenial to the insurgent Republicans of the 1990s. Although Newt Gingrich and those around him decried the hedonism of the 1960s counterculture, they shared its widespread affection for empowering technologically enabled elites, for building new businesses, and for rejecting traditional forms of governance.” [1]

“Poets and novelists today, far from glorifying the self, chronicle its disintegration.” [2]

During the space race of the late 1950s and ’60s, a photograph of the earth taken from the moon became a defining image in the cultural imagination. For the first time, people could see the world as a whole; they could start to think globally and think of the world as interconnected. It could be argued that the seed of globalism was sown. This image of Earth would also grace the cover issue of The Whole Earth Catalog (1968–1972), a countercultural magazine and product catalogue founded by the entrepreneurial Stewart Brand and his merry pranksters dropping out (and dropping acid) in the Californian expanse. The premise of the magazine was a catalogue of ‘tools’ (products) with which one could treat the body as a cybernetic being and ‘reboot’ oneself. [3]

Amidst a fading American dream, public confidence would reach a nadir through the Vietnam War, Watergate, and economic stagnation. Emerging out of civil rights struggles, groups such as the Black Panthers, Weather Underground, the Stonewall movement, hippies, and Yippies began to self-organize and question the structures of postwar American capitalist society. Youth would leave the suburbs and head to the burgeoning hippie idyll of San Francisco, before deciding it was ‘too commercial’ and heading off to desert or rural retreats to ‘drop out’ or live communally. Armed with copies of The Whole Earth, they looked toward ways of solving the upcoming problems of environmental disaster by means of self-sustainable farming and optimizing the self through biohacking. However, it is never possible to fully drop out of society; in fact, by doing so, as Fred Turner critiqued the transformation from the Stewart Brand-led counterculture to cyberculture, under a fog of neoliberalism, one could even help facilitate hypercapitalism.

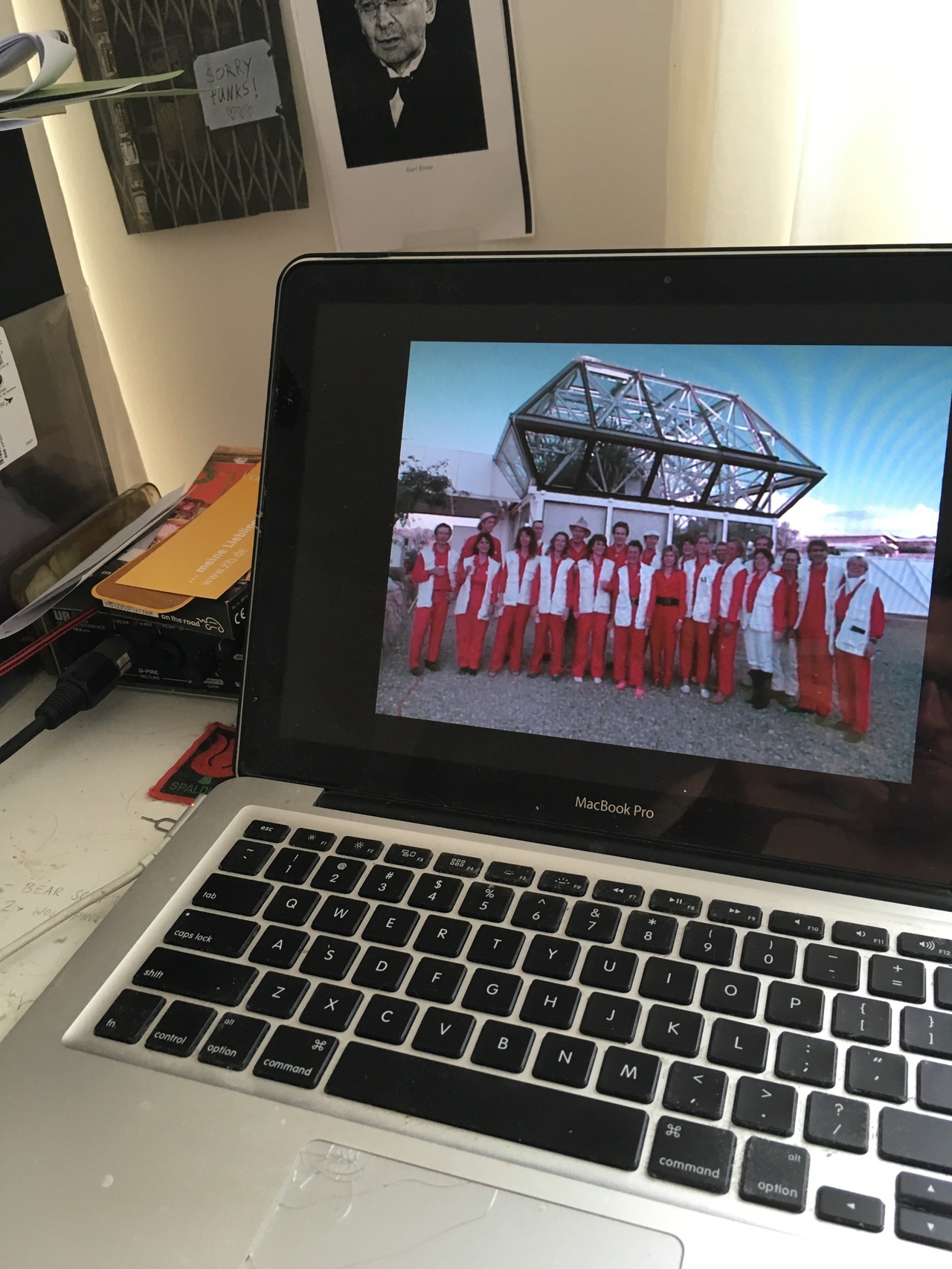

In Spaceship Earth (2020), filmmaker Matt Wolf charts the development of one such group, the Synergists, from being a performance group in the Bay Area to sailing the world’s oceans and delving into colonizing outer space with their Biosphere 2 dome. [4] The story begins with a group formed as a theater troupe named the Theater of All Possibilities, who drew on influences such as Antonin Artaud and the surrealist René Daumal (author of the 1952 allegorical novel Mount Analogue, in which a crew board a boat named Impossible in search of a mountain which doesn’t exist). It is through this performance period that the Theater had a chance encounter with Ed Bass, heir of a wealthy Texan oil family, who would go on to fund their subsequent ventures. After deciding that the hippie milieu of San Francisco had been corrupted by commercialism, the group, like many others of the era, would decamp to the New Mexico desert, where it founded Synergia Ranch. The Ranch was dedicated to sustainable farming, building geodesic domes after Buckminster Fuller, and developing their theater practice and consciousness-raising experiments. The group also constantly documented their activities, and this work makes up the bulk of the archival footage alongside interviews used in the film. [5]

There are moments in Spaceship Earth where the group’s sheer self-belief and focus on action toward various projects in search of the miraculous is impressive. Having decided it has honed its craft, the group seamlessly transitions back to San Francisco. Facing, in Jean-François Lyotard’s words, the ‘Pacific Wall,’ they construct a boat they name Heraclitis, [6] despite having no prior boatbuilding knowledge, and launch it into the ocean. This sailing Gesamtkunstwerk was considered a performance and served as a ‘laboratory’ to research the ocean biome, a theater space, and also as a vessel in which to live and travel around the world for new performances.

Outwitting Oneself

It is remarkable that a group who abandoned the San Francisco counterculture because of its emerging commercialism would go on to work closely with the heir of a billionaire Texan oil family, reputed to be the fourth richest family in the United States. Bass would put forward the capital to buy certain properties around the world, and the commune would go to them and work to enhance their value “and to understand the world experientially.” Ventures included a hotel in Kathmandu, October Gallery in London, and farming land in the Australian outback. It is with this marketing speak that the group sometimes comes across like a focus group. As member Marie Harding (a.k.a. Flash) asserts in the film, “we weren’t a commune, we were a corporation.” They started to organize conferences around the world, with speakers like William S. Burroughs addressing concerns of preserving the environment and population explosions. Much like Stewart Brand’s post-Whole Earth ventures into Silicon Valley, it begs the question to what extent the group were really posing an alternative to the capitalist society they had supposedly dropped out of.

Perhaps with the Cold War space race and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey space travel was ‘the final frontier’ to be traversed, resonating heavily in the cultural imaginary of the time. It also follows the history of mercantile capitalism, from land to sea and now space. John Allen, the founding member of the Synergists, was particularly influenced by the 1972 environmental-themed sci-fi movie Silent Running by Douglas Trumbull. Despite the dystopian tinges of the film, in which a scientist attempts to preserve the last remaining species of earth’s ecosystem on a spaceship, Allen decided he wanted to make the film a reality (even though the film ends with the protagonist blowing himself up). He made a proposal to Bass to construct a space-colony version of Noah’s Ark on earth with the Biosphere 2 (Planet Earth is Biosphere 1), recreating swamp, ocean, desert, and jungle terrain. Bass jumped at the chance to fund the project, realizing the long-term possibility of licensing out the project should space colonization become a reality (as we find in the present day with tech entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk).

The project finally came to fruition in 1991. [7] At the televised opening it is interesting to note that the moment the dome is sealed, the window is read as a screen to a world, simulating a Big Brother TV set. [8] Writing about spectacle, sociologist Erving Goffman noted “the maintenance of social distance provide[s] a way in which awe can be generated and sustained... in which the audience can be held in a state of mystification in regards to the performer.” [9] From then on, a media backlash starts to kick in and the project becomes dystopian. Public trust in the authenticity of the performance starts to falter: Who are these people after all? An interview with a former Biosphere 2 scientist states that he considers the project “trendy ecological entertainment.” Journalists are quick to compare the “cult”-like quality of the group and its leader John Allen, cynically speculating not just over whether the project will last, but also for how long. It is notable that with the cult leader comparisons, the Manson killings still resonated in the American popular consciousness, as did the conflict around the Branch Davidian sect founded by cult leader David Koresh, which was about to culminate in the Waco shootout with the FBI. [10]

In order to provide some revenue for the upkeep of the biosphere, a visitor center opened where guests could observe the space through windows. A group of African Americans visit and notice that amongst the biodiversity of the flora and fauna the team was decidedly monoculture. Answering the camera, one man states that “what we’re upset about is there’s no multiculturalism inside” and a woman asks “I would like to know what would a young black woman from Brooklyn do in a biosphere?” Despite these tensions, Biosphere 2 managed to complete its projected two-year span, although business relations collapsed soon after. On April 1, 1994 Bass invited in a group of Wall Street bankers, including Steve Bannon, to manage the project, and Bannon was installed as CEO. Scientific data charting developments in the ecosystem were promptly destroyed or locked away. [11] To quote sociologist Christopher Lasch: “politics degenerates into a struggle not for social change but for self-realization.” [12]

Historic music festivals such as Burning Man which took place in the Californian expanse began out of a 1990s deterritorialized utopian communalism but were eventually so eroded by rampant individualism that in 2015, Mark Zuckerberg flew in via private helicopter in a AV experiential take on Davos. Spaceship Earth charts this erosion, where mid-century dreaming becomes a nightmare when fused with the wild west of deregulated capitalism. It documents the transition from the emergent internet’s early utopianism (web 1.0), where cyberspace was more focused on creating a community not possible offline, to the virtual prison of 2.0 platform capitalism.

Today, the Synergia Ranch still exists and the group looks at ways to help preserve the environment collectively, contrasting with the idea of retreat in, say, Peter Thiel’s fallout shelter in New Zealand. Elon Musk recently complained of the government-ordered coronavirus shutdown as “fascist,” as he couldn’t reopen his Tesla luxury car factory. It is perhaps also telling that his go-to metaphor in a tweet is from a movie (The Matrix). [13] As we watch world events unravel largely through a media gaze, where social media tycoons profit from outrage, and Jeff Bezos is poised to become the world’s first trillionaire, we have to ask ourselves how to think toward collective solutions and agency, making sure those most vulnerable from dropping out of the system not by choice are not neglected and, when possible, avoiding lining the pockets of the 1 percent, who are locked up safely away in a fallout shelter, selfishly dropping out from any responsibility towards humanitarian crises.

Steven Warwick is an artist, writer and musician.

Notes

| [1] | Fred Turner, From Counterculture to Cyberculture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 8. |

| [2] | Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: Norton, 1979), p. 41. |

| [3] | A germ of which would develop into the wellness industry, which is particularly endemic in places such as California. |

| [4] | As I write this review, Elon Musk’s SpaceX company has launched the first private shuttle to the International Space Station. |

| [5] | Wolf frequently makes documentary films from archival footage, including his latest film, Recorder (2019), about the civil rights activist Marion Stokes. From 1979 and the Iranian revolution until the Sandy Hook massacre and her death in 2012, she constantly recorded American television on VHS tapes, preserving evidence of history and showing how television shapes our reality. |

| [6] | After the Greek philosopher famed for the maxim “change is constant.” |

| [7] | Prior to the opening, the Theater made a disaster play titled The Wrong Stuff about everything that could go wrong in the biosphere, presumably to exorcise any anxieties about the project; however, in hindsight, it eerily mirrored what was to happen. |

| [8] | Or An American Family – the first reality TV show to accidentally document the disintegration of a nuclear family. |

| [9] | Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1959), p. 57. |

| [10] | Which was also a point of influence for the domestic terrorist Ted Kaczynski, known as the Unabomber. |

| [11] | Biospherian Kathelin Gray (‘Salty’) makes the chilling point that in current debates of the reality of climate change, Bannon clearly is aware of the facts around future ecological disaster yet chooses to publicly rally against them. |

| [12] | Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism, p. 39. |

| [13] | “Why Is Elon Musk Telling Us to ‘Take the Red Pill’?” The Guardian, May 18, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2020/may/18/why-is-elon-musk-telling-us-to-take-the-red-pill. |