The Virus Is Our Idea of Ourselves by Claire Fontaine

Notice board (No handshakes), 2020

In the midst of a global crisis with no solution in sight, the strategy of total refusal appears irresponsible. No matter how explicitly corrupt and dangerous for itself and the planet the current political organization of everything is: according to most voices in the media we need constructive proposals, seemingly impossible reforms, demented trust, and a good dose of fear and submission. For many of the subjectivities who rebelled in this climate for the past forty years, organization has proven increasingly complicated and claims have become less and less federating; precariousness and fragmentation have been blamed for creating dis-homogeneous experiences. This has allowed repression to hit harder and working conditions to worsen. The dismantlement of the welfare state and workers’ rights has gone ahead whilst subjectivities were inexplicably adjusting to the disaster. Struggle has come to define the psychological trouble brought by this new condition in which fighting for one’s rights is an almost ungraspable possibility. Internalized violence doesn’t only come from one’s vulnerable socioeconomic condition, but from the burden of the political defeat that causes it. The return of fascism under so many forms wouldn’t be understandable without taking into account the lack of society’s anti-bodies against it, brought along by the depression and self-hatred of all the generations of rebels that have seen their physical and emotional world crumbling down under gentrification and mass unemployment. Debt is one of the tools of this oppression; another is widespread poverty (even amongst the employed population). Though being rather common strategies for governance, what is new is that nowadays they are experienced as deeply individual, depending on personal failures, shameful and non-federating. People of all classes sense that they have personal responsibility for an order of things that is destroying them as human beings. They resent what is ruining them but also fear the internal crisis of the power structure that is harming them, fearful that worst conditions can arise; whenever racism kills, poverty strikes, or climate change proves the impossibility of capitalism, they feel guilty and complicit rather than angry.

This phase of capitalism has managed to render integration to the productive chain as far more desirable and urgent than anything else, including health, mental balance, human relationships, and a meaningful life. The mass of the constantly excluded pressing outside the gates of whatever we ourselves are included in, the anxiety of losing one’s place is more intense and real than any solidarity toward the people in need can be. The deep awareness of being disposable is poisonous. This has allowed work to become more and more invasive in everybody’s lives and the general perception of professional experiences to be toxic, dissocializing, competitive, and selfish. Having a job is now a lonely and scary business.

And yet in the past few months work has been presented as massively unessential: the COVID-19 measures made it clear that key workers are a tiny overexploited percentage of the population; all the others can just sit back and relax or do their chatter on zoom, and the world will keep turning. In this deep financial crisis, jobs have also become increasingly hard to find and badly paid, but the superstition still stands that working is the only way to provide for one’s individual needs and only means to exist as a person; any other condition is considered a befallen one. Because the dream has become precisely what makes the dream impossible, and here capitalism shows its devilish genius: by longing for vast depopulated spaces, powerful cars, expensive lives or just having enough to live in unaffordable cities without having to work several jobs, people run the rat race and don’t fight.

The objective failure of the economy at keeping society together and preserving class solidarity simply to reproduce the species isn’t experienced as a scandal but internalized on a subjective level as the anxiety of being stuck with others that we don’t understand. The separating effect of neoliberalism and the psychological weakening of the isolated individuals is not an accident or a side effect: it’s vital for this stage of the productive process, where our mental balance needs to be cannibalized in order to secure adhesion to the unacceptable status quo. Limiting social interactions to the chosen ones isn’t seen as impoverishing but as hygienic. Self-isolation during the pandemic had something familiar, both for the social classes who have been practicing it for a long time and for many others who can’t do so: not only viruses go through the body but also power relationships. The social Darwinism of Boris Johnson’s herd immunity theory is in reality the secret murmur of all the liberalist policies, it’s the muteness of the stock market’s graphs, it’s the bureaucracy of any office, the biopower and the necropolitics that we have normalized, although they are bankrupting our lives.

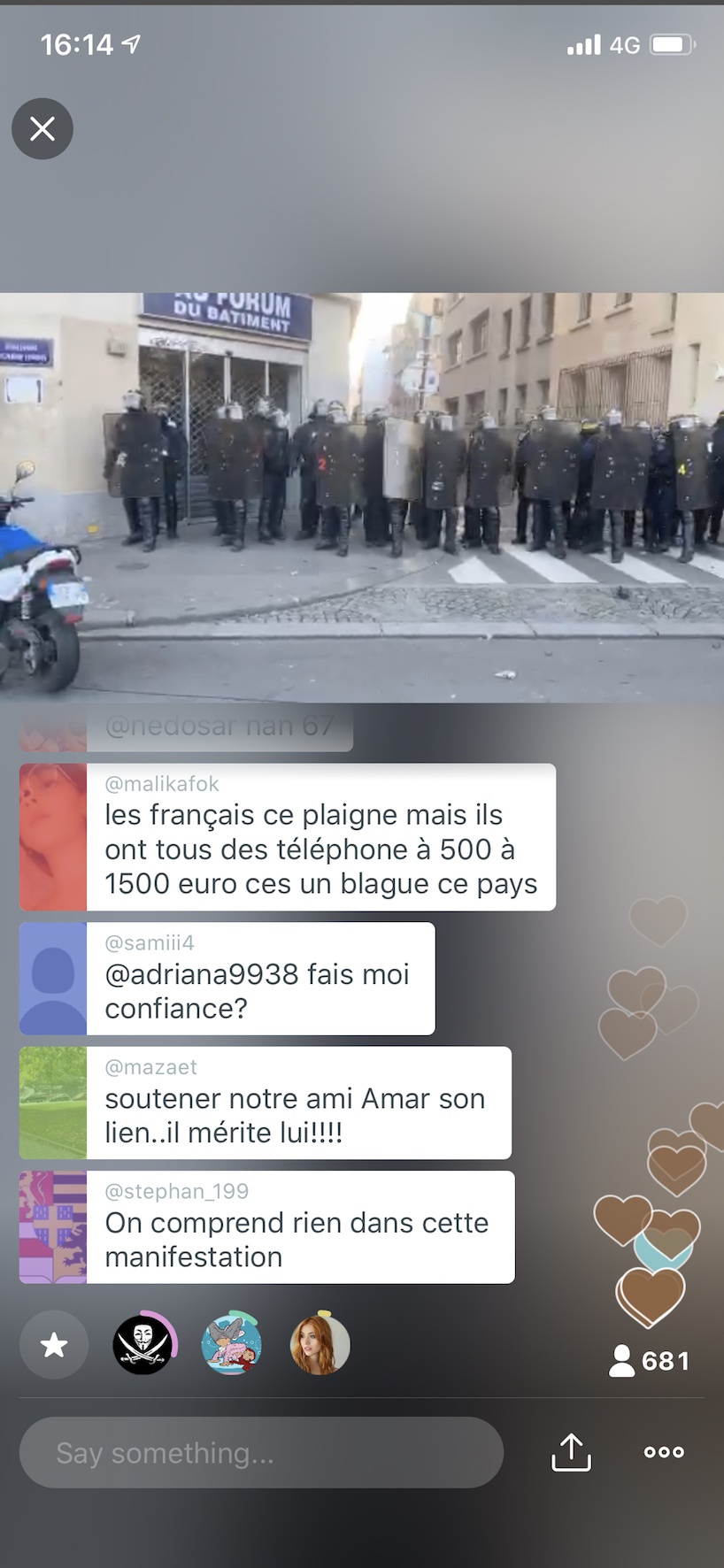

Screenshot (@TaoualitAmar broadcast tweet 18 January 2020), 2020

Survival cannot and should not be the horizon of any politics. And yet very violent explosions of conflicts have taken place in the past years amongst the populations that cannot participate in the dream of a life made of material comfort, human separation, and electronic interactions. They weren’t professionally characterized or homogeneous in terms of class, they were disorderly, transversal, intersectional, critical of the social pact that excluded them. They were human strikes.

Women have, through the women’s strikes and the #MeToo movement, highlighted the paradoxes of integrating themselves within the professional world which is ecologically unsustainable, economically and emotionally criminal, and informed by toxic ethics. (Rape as a culture goes further than the violence against women: it’s the way we, as a civilization, relate to every living source of energy and nourishment.) Indigenous and nomadic populations, who have seen for centuries their way of life definitively and unmistakably rendered impossible, now witness the achievement of a long cycle of colonization as both extraction and genocide. War, the construction of pipelines and walls, the deforestation and the depletion of any form of subsistence outside of waged work, generates profits and kills the unexploitable. Their environment being their livelihood, for some people it only takes intensive agriculture to be wiped out.

And then there are black lives: a site of extraordinary manifestation of systemic violence in all its forms. In the United States the black workforce has been kept, since desegregation, in a state of informal slavery, through exclusion, daily racism, and all sorts of institutionalized abuse, including mass incarceration and killings. Black Lives Matter has been possibly the most educational movement of the century for white people of all classes because, even more than the Black Panthers, it has taught everyone that whiteness cannot be reformed. Demanding that one’s life matters for others is beyond a political claim. Life isn’t naked before being stripped of its value by society and produced as repugnant and excludable. The looting that took place after George Floyd’s death was deemed as politically unacceptable by many, but the truth is that a certain level of outrage cannot be translated into orderly words – it’s beyond political because it points to what politics doesn’t cover: the naked life deprived of any protection. Only smashing the surroundings can echo the infinite damage done to broken people and broke households by a broken system. The lack of integration is blamed on patriarchy, racism, colonialism, but one is still left with the fact that wanting to change the (unchangeable) condition of being a woman, a Native American or black comes down to self-hatred when the reason for one’s discrimination is one’s physiological and human condition.

The deepest impoverishment comes from the lack of alternatives when faced with this blackmail: the only reformist path available for these people would be to become their own enemies, pretending that it’s possible and acceptable to enter the very system that has exterminated and rejected most of them. And the system cannot be reformed because it thrives on this rejection, on the unpaid housework, the slave labor, the pillage of natural resources. For capitalism, refusing a (symbolic, cultural, and economic) value to things is the only way of making profit from them. Because we cannot ask to mend the disaster, what is ‘radical’ now isn’t the perspective that refuses reformism, our present condition of communal but not communized humiliation, our lack of political dignity orchestrated by a system of government that has found in our self-respect a new land to colonize and destroy.

To trace lines of flight we don’t need to become invisible, to cultivate opacity, to dive into conspiracy theory, we just need to stay illegible and unaffiliated and learn how to collude with each other’s disaffiliation. Carla Lonzi wrote in 1975: “What I am is pathetically invisible and inaudible and I can’t use it. Now I am sure that I am not making a drama of it, because it is in fact a drama, my decision of not falling into the trap anymore is taken […]. I, who don’t exist socially, can recognize another woman who doesn’t exist socially and so on. But my consciousness isn’t recognized by culture so this chain of recognition between non-existing is valid only between us. I don’t see the possibility of a different man because it is unthinkable to give up the social identity that he has for one that doesn’t exist.” [3] If the man/woman relationship offers the most tragic example of the impossibility of being recognized as a political subject even inside intimate interactions, it’s because the occultation of the economic aspect of it is done through the ideology of love. In fact, not only is exploitation possible, authorized, even foundational of the social structure of our society, but it provides the model for heterosexual love. The love of the advertisements, the pop songs, the Hollywood movies is informed by the paradigms of conquest, enclosure, and private property. The mental balance of subjects resting on their relational life, the fact that entire parts of the population are simply dehumanized and represented as naked life threatens our own self-esteem: human fabric is what makes worlds because worlds happen when we can say “we.” The nonsense of patriarchy, the darkest mystery that supports its economic metabolism, is its sexual desire and supposed affection for women, who are in fact objectified, despised, and constantly discriminated against in every single social class.

From our houses where we have performed remote work we have experienced again the different intensities of gendered multitasking. We saw Deborah Haynes on July 1st being shut down by Sky News because her son barged into her home office, where she was broadcasting live, asking for two biscuits; from the studio her male colleague commented laconically “We’ll leave Deborah Haynes in full flow there with some family duties.” In 2017 Robert Kelly was subject to a similar incident on the BBC: his two toddlers bolted into the room while he was on air but his wife promptly grabbed them and the interview went on. Last March he was consulted as an authority in the matter of smart working on the Today show. The profile, titled “‘BBC Dad’ reflects on viral work-from-home moment: ‘Mostly fun, sometimes weird’” reads: “Robert Kelly, who inadvertently became a viral star in 2017 when his two children barged into a live interview he was giving, reflected on his family’s internet fame in an essay published by an Australian think tank.” [4] If a husband, a friend, someone had come to prevent Deborah Haynes’s son from insisting on-camera for his biscuits, she wouldn’t have felt the humiliation and neither would we. But she was alone, that’s why her child needed her, and that’s why she could be shut down.

Screenshot (@TaoualitAmar broadcast tweet 11 January 2020), 2020

The virus has helped us understand why self-abolition has become an appealing and more realistic perspective than either the feminism of equality or the one of difference. Maya Gonzalez and Marina Vishmidt have explored the idea of self-abolition in the specific case of gender and the eccentric position that women hold within the productive/reproductive system of society. Sharing the work of care will never be an option under patriarchy, no matter the policies: the simple fact that the conversation is taking place at a personal and at a political level, that the care of children should be and isn’t a task for men and women alike, is the sign that we are living under a regime that doesn’t value human life whenever it isn’t immediately productive, and as such is self-hating therefore unreformable. The only processes to revalue life are revolutionary, because only in the struggle, as Silvia Federici states, do we belong to ourselves.

Our expropriation runs deep and the refugees’ condition is a mirror and an allegory of it. Human masses excluded from all service and benefits of contemporary civilization are growing. According to the UN Refugee Agency, in 2020 at least 79.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee their homes. Among them are nearly 26 million refugees, around half of whom are under the age of 18. The time has come for the hypocrisy of the humanitarian ideology, through which capitalism preserves its progressive and civilizing image, to be unmasked: human rights are not being protected because there have never been any rights outside of workers’ rights, the ones that had been fought for in productive places, where strikes could actually cause quantifiable economic losses. All other struggles have been of a revolutionary nature and they have demanded a change of civilization, a change of paradigm of perception and understanding reality, the revolution of the current system of value.

As long as private property, with all its psychological and physiological ravages will be interpreted as a “reasonable” or “necessary” distribution of the sensible, we won’t be able to think. This means that for now millions of subjectivities cannot exist; they are in the limbo of naked life and can’t access any symbolic status, any political revolt. There is no rationality on the side of the world governance that can bind us to any loyalty in front of this. There is no identity based on institutional recognition that will allow us to transform the current state of things. We need to struggle as whatever singularities. We need to go on strike from our production and reproduction of subjectivity, we call the strike that will modify both the political situation and ourselves in the process, the human strike. It can be quiet, imperceptible and deeply transformative, irreversible. We can abolish the meaning of being black or being a woman as we abolished the one of being a slave. We won’t be complicit in our oppression. An Italian feminist slogan says “We don’t believe what they say about us,” we must negotiate the terms of how we are perceived and valued. The same must be done with every form of identity, the ones that burden us because they carry a stigma and the ones that separate us from others because they are privileged: they both need to be dismantled, they are both forms of submission.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the lack of value that human life has under our current political regime, the toxicity of our daily living conditions, and how easily our solitude and surveillance can be enforced by different governments. Fred Moten writes in The Undercommons that “the coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?” [5]

Now these findings are in our hands and we no longer need to respect what doesn’t respect us. We need lines of flight that help us to become complicit in our dispossession rather than our submission, to transform it into a communal force, shape a reality that is never represented and never will be: that reality is illegible because it’s yet to be written.

Claire Fontaine is a collective feminist conceptual artist, founded in Paris in 2004 and currently based in Palermo. An anthology of her writings entitled Human Strike and the Art of Creating Freedom will be published by Semiotext(e) in 2020.

Image Credit: Claire Fontaine

Notes

| [1] | Herman Melville, Bartleby, The Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street, 1856. |

| [2] | Jack Halberstam, “The Wild Beyond: With and for the Undercommons,” introduction to The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, by Stefano Harvey and Fred Moten (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), p. 8. |

| [3] | Carla Lonzi, Taci, anzi parla. Diario di una femminista (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1978), pp. 1172–1173. [Translation by the authors.] |

| [4] | Scott Stump, “‘BBC Dad’ reflects on viral work-from-home moment: ‘Mostly fun, sometimes weird,’” Today, NBC, March 17, 2020 [March 13, 2018], https://www.today.com/parents/bbc-dad-revisits-his-family-s-viral-moment-one-year-t124934. |

| [5] | Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, pp. 140–141. |