TRANS MED PANIC AND THE FAUX PAS CLOCK Coco Klockner on recasting “The Bourne Legacy”

Rian Ciela Hammond, “Root Picker,” 2021

Tragedy keeps a tight grip as a dominant mode in trans cinema and literature, despite efforts to dethrone it. The optimists usually label this a problem for what it signals for trans people living in the world, arguing how scenes of life could fuel these stories just as well as scenes of death can. I’m not necessarily an optimist – being trans can feel tragic. I find solace in the warmth that pessimism provides, that tragedy as an inextricable thread in trans ontology offers. Still, I understand the impulse and find myself siding with the optimists looking for new genre forms for a different reason: sometimes, frankly, I’m tired of tragedy. A repeating genre goes stale once we’re familiar with the rote, dried-up rhythm of its arcs and valleys.

A question: What would it mean to recast the 2012 mass-market action-thriller The Bourne Legacy as a trans film? Perhaps that if there is something fungible within this narrative arc, it is resonant precisely because of, rather than in spite of, its distance from transness.

The fourth in the five-part series imagines new – certainly not implausible – nefarious methods of fictitious US Department of Defense and CIA black ops super-agent programs. Within the otherwise familiar cinematic structure of a world like the Bourne universe and its handwringing ambivalence toward imperialism, an unintended trans allegory emerges that eschews the broad strokes of generalizing moralisms in favor of a specific vignette archetype that could be called the “trans med panic.” Such a narrative device might describe a wide spectrum of various issues in medical access for trans people, ranging from simple delayed prescription refills to the more significant anxiety of forced medical detransition by unilateral policy or democratic legislative change; here, though, we see it framed through the cis imagination, in the dysmorphic relationship that cis people maintain with their own bodies.

The Bourne Legacy follows protagonist Aaron Cross (Jeremy Renner), an agent of “Operation Outcome,” who relies daily on 250 mg of “greens” and 400 mg of “blues” from the program to enhance his physical and cognitive abilities. As the program forces its augmented participants to act in service of empire maintenance, Cross finds adhering to his moral compass an impossibility. As if confirming these moral positions, when an intel leak threatens the program and the research that drives it, the director decides to destroy it, enacting a plan to kill its agents and civilian scientists in order to reboot the program at a later date.

What the audience is left with in this premise is a two-hour chase as the government mobilizes to eliminate our protagonist; all the while, a narrow window of time closes in before the meds wear off and he goes into decline. Against the very nature of trans health care and the global backlash against minor victories for trans rights, the allegory is piercing: I flash back to a time that I raced across town to retrieve a forgotten hormone-filled backpack from a stranger’s basement for a friend on tour so I could illegally overnight the meds to her in the city she had reached by the time she noticed they were missing; I remember the times I’ve given and been given hormones by the loose DIY network of trans people who help each other navigate diminished medical access. Maybe the genre has been “action” the whole time.

Even in the film’s minor moments adjacent to this larger arc, an audience can identify archetypal trans exchanges such as “the faux pas clock.” Encountering an agent in the field who hasn’t yet identified himself, Cross clocks him as one, receives a look in return, and immediately apologizes – “Look, I’m sorry to call you out like that, it’s just that I’ve never met anybody in the program before” – before proceeding to ask for meds. Clocking strangers in public can be fraught; there is, in most scenarios, some appropriate performance of a recognizing look absent of the crude tools of articulation, something that provides a sense of safety in numbers without the overstepping of certain boundaries. Identifying a look of one quality might indicate the very desire to talk about transness, whereas another might indicate that “you literally don’t know me like that.” [1]

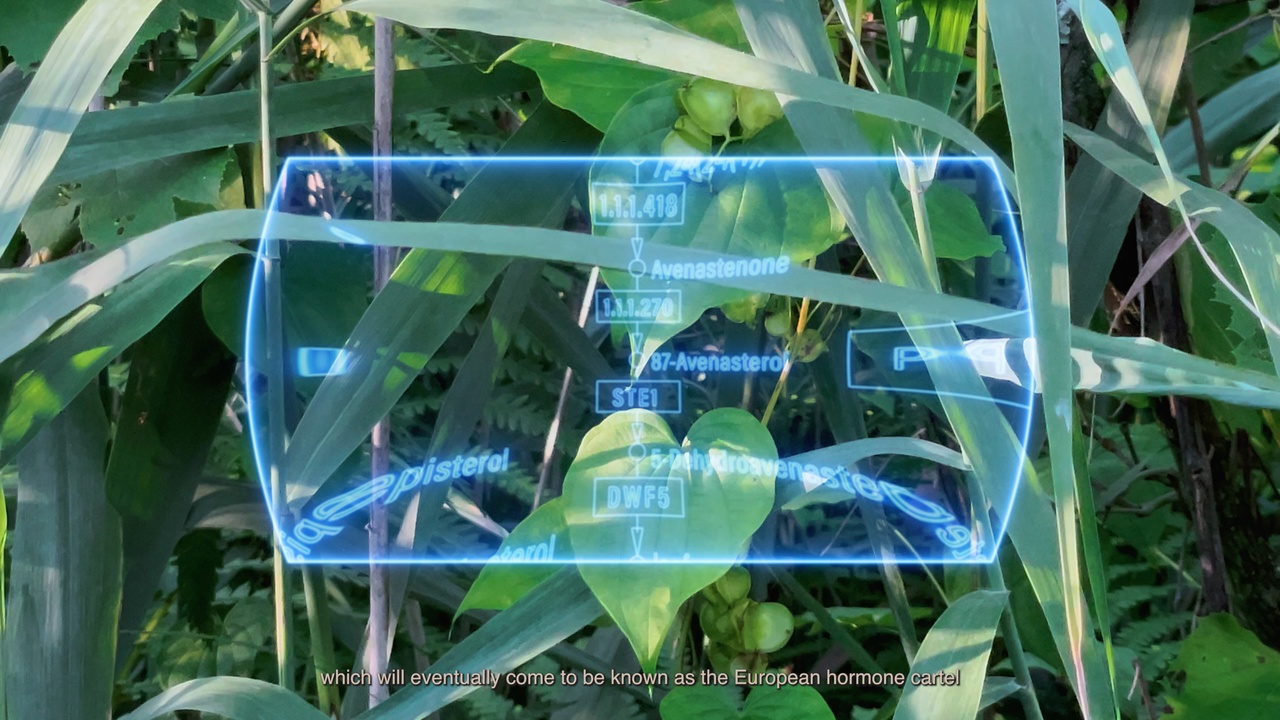

In a plot device conceived for this depicted universe, Cross is ultimately able to access the live viral stems his meds were built from in order to then “viral off” of them, making his body alterations permanent. Another common narrative form would have a trans protagonist forced to encounter the “unnatural” nature of their transition desires, and yet, in this cis context, desire is a non-problem. The works of artist/researchers Rian Ciela Hammond and Mary Maggic come to mind: both artists explore open-source synthesis and extraction of hormones to look at how these pharmaceutical technologies emerged and proliferated – often as efforts to eliminate gender non-conforming bodies rather than to enable them – and imagine more accessible futures. Such research could aid in the extraction of certain processes from the hands of the entrepreneurial, aiding more decentralized methods for post-collapse hormone replacement therapy – hopeful tactics for those of us with some distrust in the medical systems that still enable merely conditional modes of our existence. Perhaps such developments pave the way for a typical action-movie ending – our protagonist on a boat with lover in hand, sailing into the sunset, billowing smoke in the distance, permanent HRT future.

Coco Klockner is an artist and writer based in New York. She is the author of K-Y (Genderfail Press, 2019) and her essays have appeared in Spike Art Magazine, *Real Life, and Disclaimer/Liquid Architecture. Recent solo exhibitions have been held at Silke Lindner, New York (2022) and The Anderson, Richmond, Virginia (2019).

Image credit: Courtesy of the artist

Notes

| [1] | It’s worth noting that in the process of identifying trans allegories in cis cinema, this question of respected boundaries is similarly approached simply in the fact that trans audiences briefly get to imagine a film apparatus that doesn’t forcefully clock its trans subjects for an implied cis gaze. |