SAINT AGATHA AS A BOY Katayoun Jalilipour in conversation with D Mortimer

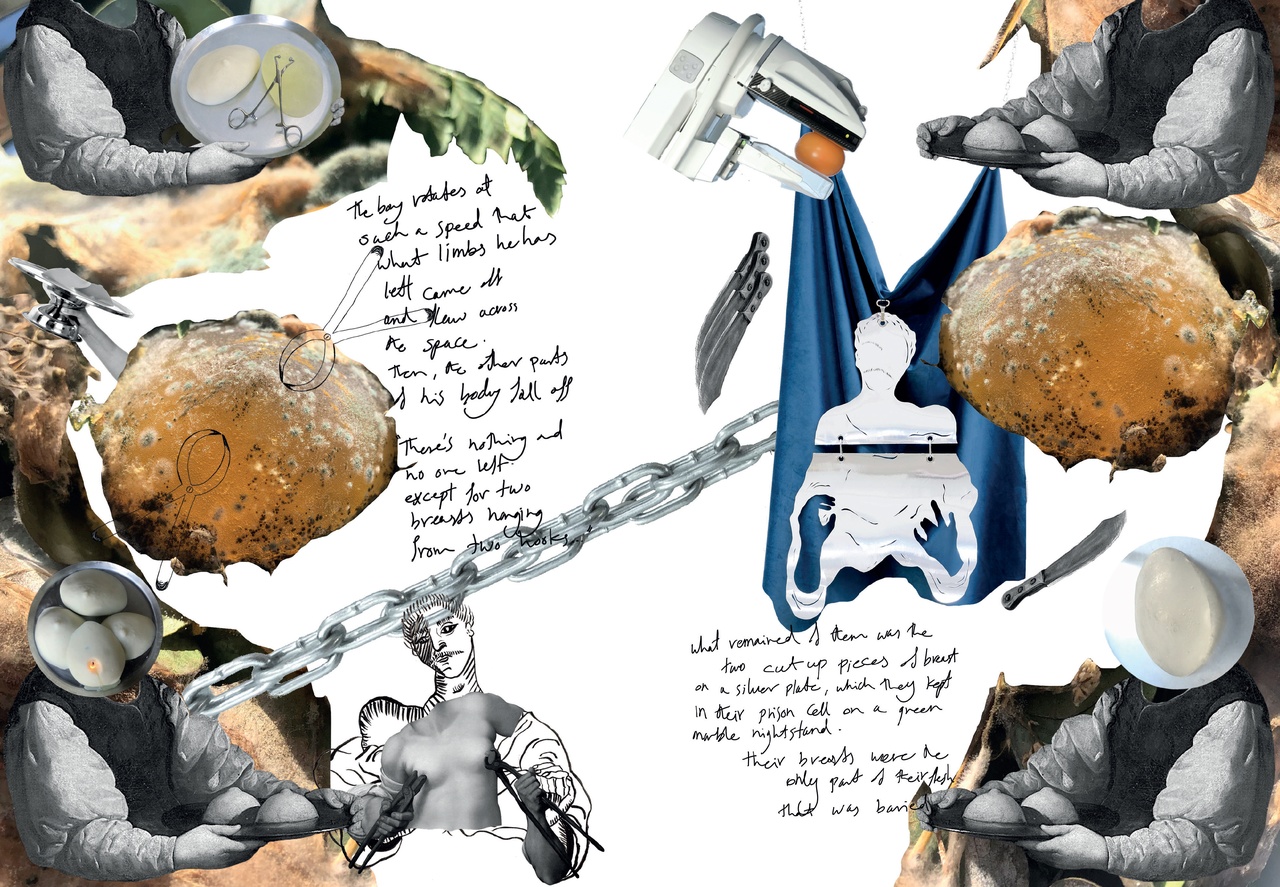

Katayoun Jalilipour, “Study of Saint Agatha as a Boy, No 4,” 2023

D Mortimer: When did you first hear about Saint Agatha and the legend associated with her? Why was it important for you to reinvent her narrative in the way you did in a recent series of projects, such as Studies of Saint Agatha as a Boy, which is part of the image spread of the last TZK issue?

Katayoun Jalilipour: I first heard about Saint Agatha on a university trip to Prague in 2015. I visited a museum that had a painting of her on display. Then someone told me the backstory and I became obsessed with her. For years the image of her with her breasts on the plate haunted me and I had to make sense of this obsession somehow. One day it finally clicked that it was all about this trans narrative and that I could reinvent or reclaim her story in relationship to myself and the people I know.

DM: You are a wildly cross disciplinary artist, using text, drawing, painting, laser cuts, clay, video, and gifs in your work. How do you decide which concept demands which vehicle for expression?

KJ: I think it all happens in the making. I don’t really know what the final result is until I try it and it fits. I usually start with a drawing by hand, or a digital collage, just to see what forms, shapes, and colors stick out for me. With this piece, Studies of Saint Agatha as a Boy, it was important to establish clear connections to the historical paintings of her. I studied specific ones, for example the Bernardo Cavallino painting from 1640, and then it made sense for my work to be sculptural, to bring aspects of the original paintings to life in my own style.

DM: Tell us a bit about your idea of non-durability.

KJ: I read somewhere that if humanity disappeared all at once, bronze sculptures will be some of the last artifacts from our civilization that will remain. This really fascinated me, so I started to think about durability in sculpture. I play with the idea of organic versus nonorganic, soft versus hard, like juxtaposing jelly with the stainless steel plates. I take a lot of inspiration from Louise Bourgeois, who worked with similar concepts of contrasting materialities. With this particular work, I’m interested in how the breasts in the paintings are displayed as sculptural objects themselves even though they are human flesh. I’ve been playing with flesh-like material such as gelatin and latex and jelly wax, all of which decay over time, like flesh would. I’m also interested in making the work sustainable and thinking about how long a sculpture or any piece of art can or should last, and the performativity of that.

DM: When I first saw your gelatin molds of breasts I became aware of a feeling of guilt. These representations of breasts, which are caught in various stages of degradation, caused me to think of letting the body go to seed and the moralism, racism, classism, and sexism associated with not caring for one’s physical form. As someone who is read as female 70 percent of the time and someone who has been socialized as female, I have been taught there is something grotesque and unsightly about neglecting the body or choosing not to conform to a standard of beauty associated with being read as a woman. It raised this question for me: What happens if we hold ambivalence, or even disgust, for parts of our bodies, like our breasts? What if we built a system of care that supports the oxymoronic truism that caring for parts of ourselves sometimes means letting them go. This is a truism that is unthinkable to the present state of trans healthcare in the UK. The National Health Service (NHS) filibusters and blocks calls for adequate trans healthcare. You’ve been quite explicit about the fact this work is about trans surgeries; in what ways do you feel it contributes to this discussion?

KJ: This is super important and something I relate to deeply. I remember years ago at a screening of Mania Akbari’s film 10 + 4 (2007), which explores her journey with having breast cancer in Iran. In the Q&A, she talked about how doctors encourage women who have had a double mastectomy to recreate their breasts. This is something that really stuck with me for year. Agatha is the patron saint of breast cancer. In a version of Agatha’s story, her breasts are restored by Saint Peter before she dies in prison. It’s as if she could not have been a full woman without her breasts. I think it’s also interesting that losing body parts without any choice in the matter is seen as somehow noble and worthy of sainthood or martyrdom, but making the decision to change your body is not seen as noble but “an extraordinary act of self-inflicted violence,” as literary critic Germaine Greer has previously put it. Historically, people prefer to celebrate resistance against pain and illness, rather than bodily autonomy and making one’s own choices, and I think that’s deeply sad as both things are equally important. The whole concept of martyrdom and sainthood is messed up in my opinion: to celebrate death and destruction in that way, or to encourage people to aspire to suffering, which was a big part of my upbringing in Iran and the post Iran-Iraq war narratives. Through claiming Saint Agatha as a trans masculine saint, I am writing a new narrative that celebrates the cutting of breasts as Agatha’s choice rather than something that was forced upon them, as the latter is very much the current transphobic and anti-gender-affirming surgery narrative. Trans people, especially young trans people, are painted as victims of medical manipulation and told that they don’t know what they’re doing and that they lack the ability to make their own choices about their bodies.

Bernardo Cavallino, „Saint Agatha,” 1640

DM: There is a history of rewriting and reimagining myth from feminist and queer perspectives. Off the top of my head, Björk’s song “Venus as a Boy” (1993) and the recent Globe theatre production of I, Joan (2022) by trans masculine playwright Charlie Josephine that recasts Joan of Arc as a nonbinary person come to me. Were any of these examples present in your drafting process? Or maybe you can talk about some influences we might not know about?

KJ: I’m obsessed with Joan of Arc, and there are clear links between Joan and Agatha. In some paintings of Agatha, for example, those by Sebastiano del Piombo (1520) and Cavallino, Agatha is depicted in a masculine way, for example very muscular or with hints of facial hair. Another one of my obsessions is Angela Carter’s novel The Passion of New Eve (1977), which again has this narrative of forced “sex change” surgery in a dystopian landscape. I think it is underrated as a piece of fiction and can have some amazingly pro-trans readings, which is how I choose to read it. Carter’s talent for rewriting fairy tales and making them her own is inspiring to me and has influenced the way I approach storytelling.

DM: Your work also reminded me of the Amazons in Greek mythology, a fearsome tribe of woman warriors. Many think that the word Amazones is a derivation of the Greek a-, “without,” and mazós, “breast.” The idea that Amazons cut or cauterized their right breasts in order to have better bow control offered a kind of savage plausibility that appealed to the Greeks. Although Amazon women were said to have removed one breast to make shooting an arrow easier, it is tempting to think there was a queer component to this practice too. Similarly, the race car driver Violette Morris (profiled in the podcast Bad Gays) had her breasts cut off in the early 20th century ostensibly so she could drive a car with greater ease. It begs the question: Has it always been the case that trans people have had to lie or, at the very least, bend the truth to get the healthcare they needed? There is another argument, that bows and cars and guitars weren’t made for people with breasts, and that the parts of the machine, not the body, are truly what need changing. Are we all just searching for a social model of transition? Yet even with a social reading, the question remains: Why did Violette choose to change her body and not her car, which was surely the less radical option? It is fun to delve imaginatively into the drives and desires of these early forerunners of body modification. Visual art can make claims on the past that, in academia, would be necessary to staunchly back up. Even with the growing acceptance of the critical fabulation method, there is still a lot of catching up to do in academic institutions. I wonder where you think the most interesting examples of trans culture are being made now?

KJ: There are so many trans narratives that have been erased by binary thinking; like in Violette’s case, there must have been some gender stuff going on there! I think porn made by and for trans people is one of the most important and interesting examples of trans cultural production today. A lot of trans people have not fully seen ourselves represented until we’ve witnessed trans porn. I think queer porn is art! Trans people have been mystified and mythologized for far too long, especially in visual mediums like film. Both our bodies but also our stories. I really think queer-made trans porn is where trans people get to fully be themselves, but it’s also an important archive of history of how we do intimacy, love, chaos, and sex! Production companies like CrashPad have this huge archive of trans and queer porn made by and for queer people, and honestly, if the whole world burns down and that’s all that is left of human history, I’d be pretty happy!

DM: There is something very striking and medical about your images of breast forms on meat hooks and in clamps. I am reminded again of Greek versions of metamorphosis. The metamorphosis according to Ovid is often instantaneous and painless. The sterile bloodless atmosphere in these images also seems to wrest vitality and an awareness of pain from what’s happening and is also suggestive of a kind of passivity. The breasts on the plate remind me of Salome with John the Baptist’s head on a platter and the semantic melding of surgery and eating (table, knives, flesh). Your wobbly breast forms under see-through cloches resemble delicious jellies. It’s a kind of morbid humor. Would I be right in saying this? One that cynically undercuts a male literary and artistic tradition that has historically fetishized and defiled bodies with breasts.

Katayoun Jalilipour, “Study of Saint Agatha as a Boy, No 3,” 2023

KJ: I want there to be dark humor. I do hope people laugh at the work. It’s something I aspire to do in both text and visual art. Greek mythology really fascinates me. For example, how Romans used Greek myths to dress up and sell Christianity to the world. Many of the saints and even Jesus are based on symbolisms in Greek mythology (Jesus is clearly the queer god of wine, Dionysus). This history gives a whole new meaning to this work too. I don’t personally believe that Agatha existed. I believe a version of the story could have existed, as many early Christians were in fact prosecuted by Romans. But I think that there are a lot of myths around sainthood stories in general, things that don’t scientifically make sense. I’m an atheist who grew up believing two different Abrahamic religions, so for me religion is very loaded, and I definitely like to poke fun at where the loopholes are. I also find it fascinating how stories are told and how they evolve with time. It’s been interesting imagining how the cutting of breasts would have actually happened for instance. Many of the paintings present an unrealistic picture, so in using the medical equipment, I’m interested in exploring that further and imagining what it would look like today with the advances in medicine.

DM: How do ideas of the phantom, the subconscious, the passive and the dominant play into your work, if at all? I am struck with the clash of surgical implements and metalwear like chains, which are more usually associated with kink practice. Was this an element you wanted to explore? I know in the past the leather lexicon has been important to your work.

KJ: There is a kink element to the work. I think there’s a strong medical kink theme going on with all the stainless steel plates and medical tools. I think a lot of stories like Agatha’s were potentially invented by kinky monks! The queer aesthetics used in the work are a deliberate way of relating it back to queer cultures, histories, and desires, which is a big impulse in my work.

DM: There is a deft humor in the rhyme between the shape of the cloche and the breast. The suggested lifting of the cloche to reveal the carnal delights of what is underneath is succulently disrupted by the transparency of the cloche. We can plainly see a breast is underneath, which renders the psychic potency of the cloche impotent. Was this sleight of camp intentional?

KJ: That’s a good point. Actually, no! I didn’t think about it in that way. But it was a way of exploring the culinary aspect of the myth. On the Feast of Saint Agatha in Catania, Sicily, breast-shaped cakes are made and eaten. The fact that Catholicism is quite a strict branch of Christianity that forbids pleasures of the flesh, and yet, for this occasion, breast-shaped cakes are eaten by adults and children. It is wonderful and weird, so as well as the medicalization aspect, there’s also the culinary aspect, which reflects the depictions of Agatha, often with a mundane look on her face, holding her breasts on a plate as if they’re going to be served for dessert.

DM: The thing about surgeries is that it’s all a “what if” scenario; you are leveraging the cost-benefit ratio of surgery against the projected comfort of your future self. If I do this, I may feel better. It’s like, for those thinking about top surgery, we are our own hedge fund managers, and the surgeon is the broker. In many ways this is analogous to the process of making any creative work at all: it begins in the imagination before any implementation can take place. Is this artwork a kind of calculation? A kind of projection into the future via the past? It certainly feels like a ritual to me at points. You cast your own chest for this work, can you tell me a bit about that process? Are you, too, wagering on a future?

KJ: My friend Claye Bowler recently had a solo show at the Henry Moore institute titled “Top,” which archives his top surgery journey. It’s an incredible project made up of various casts of his body. It also documents his calculations for surgery costs. It’s such an important piece of contemporary trans art. Something we have in common is this interest in archiving the body as a “before,” and I guess I sort of did that without the intention at the time, when I cast my chest. It was so surreal holding the warm Jesmonite cast of my breasts in my hands and then putting them down and feeling a relief, only to realize I still had them on my chest. This was an obvious moment for me that there was something going on there. That was nearly three years ago. Since then, I have made many more casts. And the more I develop the work and make various casts of it in different materials, the more I feel like I am giving myself permission to make choices for my body. I totally recommend to everyone to cast the body part that they feel uncomfortable about and hold it in their hands, both as an act of self-love but also as a permission to change it if they want or can.

DM: You recently staged a live performance/reading of the work at CLAY Leeds. Can you tell us a bit about that experience?

KJ: I wrote a text recently titled “Agatha’s Revenge,” published by Montez Press. It’s an exploration of Agatha’s story, other stories of intimacy and violence spanning over time and place, and some autobiographical stories too. I really wanted to hear and see it through another person’s voice and vision. I did a residency at CLAY: Centre for Live Art Yorkshire and directed it as a monologue performed by a Leeds-based trans performer named Orange, who did such an beautiful job. The idea was to bring all my research on Agatha together in one show. Which included the text and the sculptural work and evidence of my sordid past as a live artist; all of it came out of the woodwork. It was an incredible experience to witness the performance as a spectator. The set was made up of the sculptures, and it became very theatrical, which was interesting since I have a performance design degree but had never before made such theatrical work. In the process I managed to make friends with performance art again and I am currently thinking about making a full-length show. I will be back at CLAY in August to create a new iteration of Studies of Saint Agatha as a Boy as a window exhibition, which I’m psyched for!

Katayoun Jalilipour is an Iranian-born multidisciplinary artist, writer, and educator, currently based in the United Kingdom. Through humor, provocation, and storytelling, their practice uses the body as the subject to discuss race, gender identity, and sexuality. They often use methods of speculative fiction to retell historical stories through a queer lens.

D Mortimer is a writer from London occupied with experimental trans and queer narratives. They are working on ideas of salmon and heartbreak at the moment. Their work (essays, poetry, prose, creative criticism) has been published by The Guardian and Granta Magazine. They are currently doing a practice based PhD in Creative Writing at The University of Roehampton.

Image credit: 1. Courtesy of the artist, 2. Detroit Institute of Arts, public domain, 3. photo Stuart Whipps